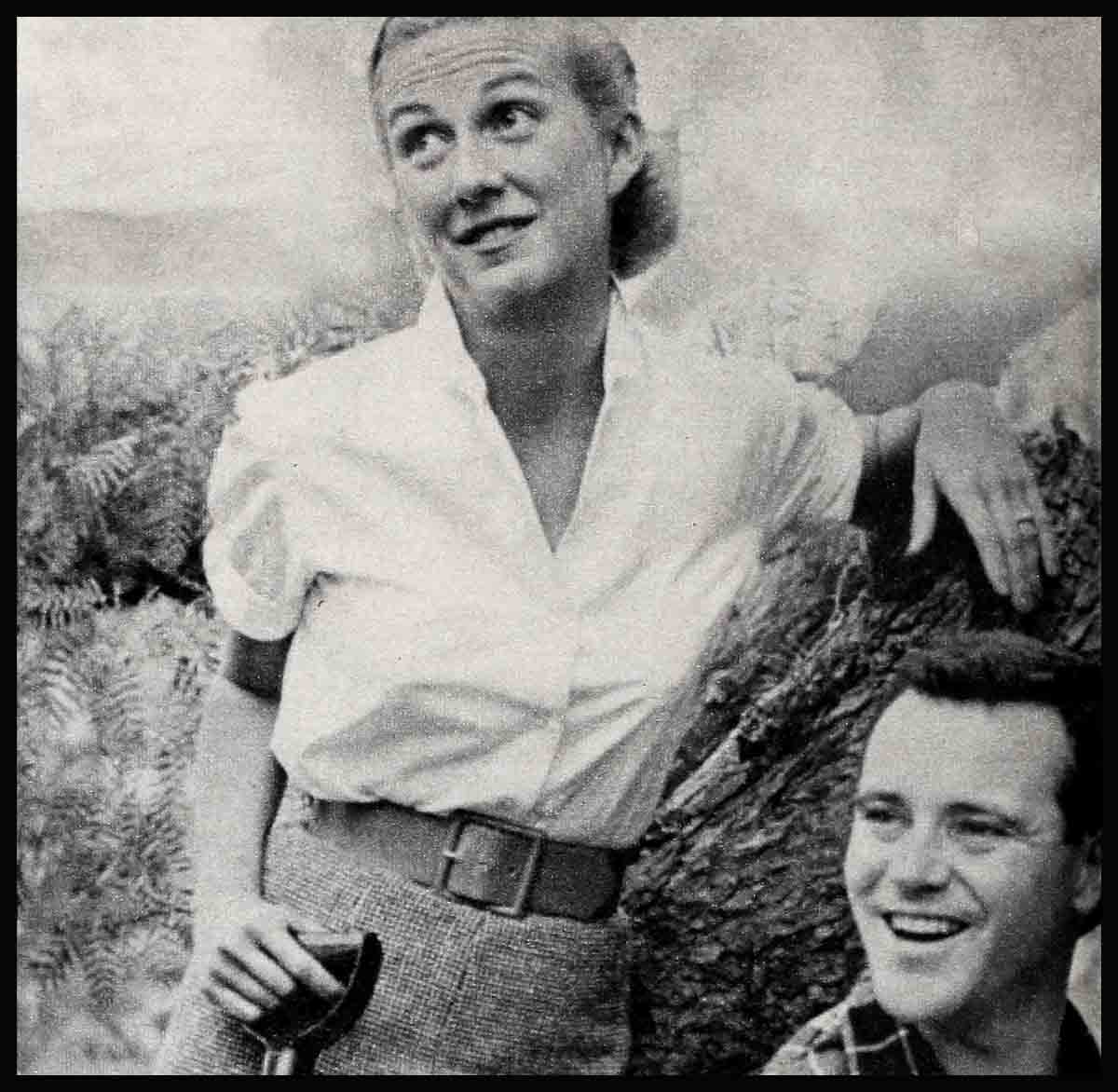

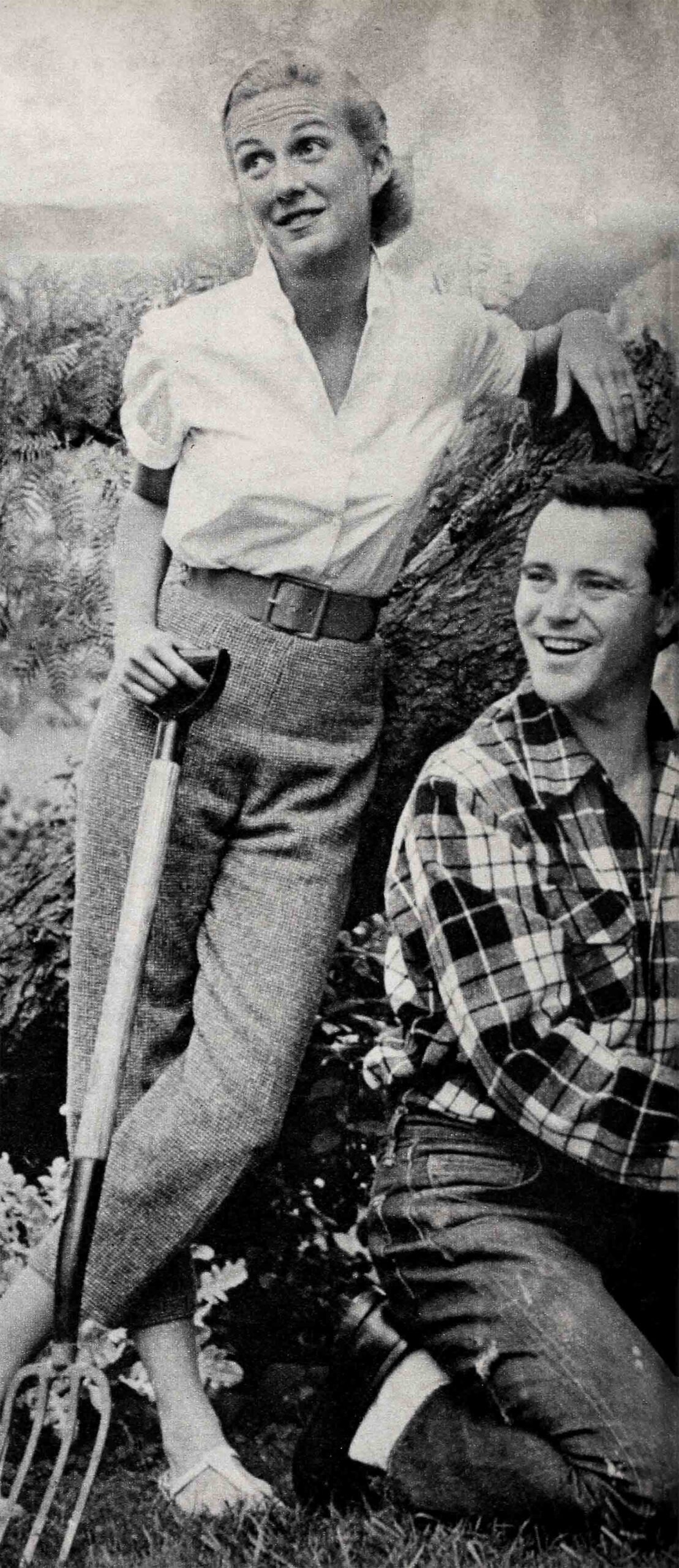

“I Fainted When He Kissed Me!”—Jack Lemmon & Cynthia Stone

The first time my husband Jack Lemmon kissed me, I fainted.

But it wasn’t from love. I was simply exhausted. Our romance had been wearing me out—but maybe I had better start at the beginning. . . .

Back in the late forties, I was a model at Saks Fifth Avenue. Actually, my heart had been set on acting, but except for some summer stock and a few radio parts, I hadn’t gotten anywhere. Then I heard that Uta Hagen was casting Tolstoy’s “The Power of Darkness.”

Shortly after lunch one day, I walked to her studio for an audition. There I met not only Uta, but a most charming young Harvard graduate—probably the only actor in New York with less professional experience than I—Jack Uhler Lemmon III. As Bostonian as all that.

I didn’t take a particular interest in him, at least I tried not to, because I was engaged at the time. What made it worse—in Jack’s eyes anyway—my fiancé was a Yale man.

After the audition, Uta Hagen gave Jack and me the leads, and we were on the way to what I wouldn’t exactly call Academy Award-winning performances. If mine was a little better than Jack’s, it was for one, and only one, reason: because of my radio background I spoke more softly—which meant that, in the actual performance, the audience couldn’t hear me at all. But anyone who was there on opening night agreed this was lucky!

I soon realized that Jack was very proper, very conservative, very Bostonian in his approach. He didn’t make any rapid advances. He waited for a whole hour before asking me for a date—and then in a roundabout way.

“I hope you don’t consider me forward if I suggest we rehearse after hours, too,” he ventured.

In spite of my loyalty to Yale, I didn’t think this was forward at all—till I found out what Jack U. Lemmon III considered rehearsing.

“We’ll have supper at the Automat first,” he suggested. Later, I found out he had to forego his lunch to pay for it.

After supper, he suggested a walk through Central Park. My loyalty to Yale started to waver still more, and I accepted that, too. It was Jack’s turn to be surprised when I recommended finishing the evening with a cup of coffee at my apartment. At last the Bostonian in him showed: “Are you sure you want me to come in?”

“Sure I’m sure. I want you to meet my roommates—Ski, Heui, and Pat.”

This was proper enough even for him. He came up.

From then on, Jack and I saw lots of one another, thanks to our mutual liking for each other, the influence of our good friends, the Alpertsons, who were all in favor of a romantic union between the two of us, and the fact that I soon broke off my engagement to the Yale man.

Yet at that time, marriage was completely out of the question. Jack simply couldn’t afford it. For a while he couldn’t even have taken me out for dinner, if it weren’t for a unique job he had.

He was employed by a chain restaurant as a checker. Every night we had to eat at a different one of their restaurants, order all we wanted and, depending on whether the service was good or bad, leave a $5.00 tip—provided by the company—or mail a letter of complaint to the head office. This job was fine—until company officials realized that Jack wasn’t very loyal in his efforts: he always left tips, never complained.

Of course, Jack didn’t get paid for this service, but the free meals certainly made our courting period a lot more agreeable.

Because of my radio experience, skimpy as it was at the time, I was able to give Jack some pointers on his work. Till then he had appeared only in night clubs, before a visual audience. When he performed, he put more emphasis into his gestures and expressions than into his voice—which would never do for radio.

I still remember the afternoon we went to my apartment, and Jack started to read the longest monologues he could find.

“Now if my voice isn’t right, you tell me,” he requested.

I nodded approvingly.

“And don’t be afraid to criticize.”

“I won’t, Jack.” Then I got myself a chair, carried it to the window and looked out. “All right, go ahead.”

“Are you kidding?” he exclaimed.

“This is the only way I can judge your voice without being influenced by your gestures,” I explained.

It made sense to him, and we spent most of the afternoon and evening going through the script.

Of how much value my coaching was, I don’t know, but the next day Jack had his first radio audition, which resulted in his playing the lead in a daytime serial called The Brighter Day for a whole year.

At that time, Jack also had a job at the Old Nick, a sort of cabaret house where he played the piano and had to sing “By the sea, by the sea, by the beautiful sea” faster than any of the customers. If any of them could beat his time, they would win $10, and Jack would possibly have lost his job. Neither was the case. Come to think of it, this must have been where he learned to sing, as well as talk, as fast as he can. No wonder I don’t have a chance to win an argument—I can’t talk fast enough to keep up with him!

Anyway, walking home one night, Jack asked me if I would like to see the show at the Old Nick. I told him I’d be delighted. However, I didn’t realize that it lasted till three in the morning—and I had to be on the job at Saks Fifth Avenue by nine. But it was fun, and we soon made a habit of it, usually having breakfast at a small place on Third Avenue afterwards. But before long, the strain began to show on me. Unfortunately, at the worst possible time—or was it?

It was close to five a.m. when we reached the lobby of my apartment building. Jack opened the door for me and, as he handed back the key, kissed me for the first time. That was when I fainted!

The next thing I remember, I was looking up at Jack’s and my roommates’ worried faces, leaning over me. “I didn’t know I had such an effect on women,” Jack grinned.

A good night’s sleep and a couple of “early evenings” fixed me up again.

I guess, in a way, I knew that eventually Jack and I would get married. But I didn’t want him to take me for granted to the point of not even proposing—which nearly happened.

One evening as we drove home in a cab—times were getting better—Jack casually remarked, “And when we are married. . .”

“Is this a proposal?” I exclaimed.

Jack reacted in typical male fashion. “Well, I thought you and I had an understanding. . .”

I had no intention of letting him get out of this one! I asked the driver to let us off at the next drugstore, much to Jack’s surprised “What for?”

“Wait and see,” I replied, heading inside and sitting down at the counter.

While the waiter brought us a couple of Cokes, I pulled a paper napkin out of the holder, and on it scribbled a marriage contract “with no options.”

“If you meant what you said, sign here.”

Cheerfully, Jack marked down his “X.”

The next day, he spent $150 out of his savings of $151.27 on an engagement ring. We were married a few weeks later—on May 8th, 1950—at my home in Peoria.

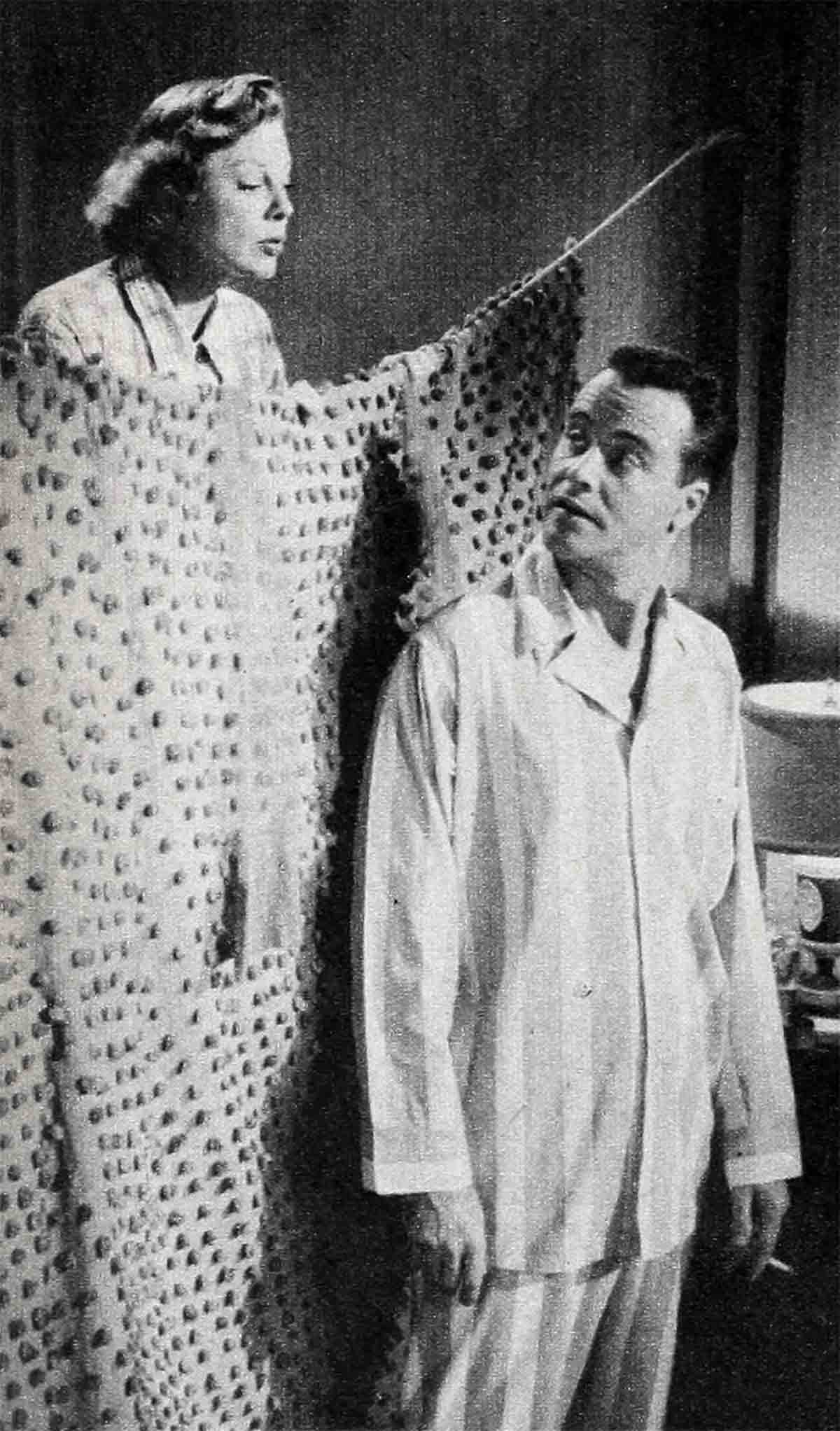

Fortunately, our honeymoon was no indication of the rest of our married life, so far. Jack suffered terribly!

We headed for Miami Beach, Florida, because it was romantic, and also because it was the end of the season and prices were much lower.

I’m sure everyone at the hotel must have known we were newlyweds. It showed all over. That’s why the room-service waiter was doubly surprised when at two o’clock in the morning of our third cay there, I called him and asked for two bottles of vinegar.

“Are you going to fix salad at this time?” he asked disbelievingly when he delivered the vinegar to the door.

“No,” I replied. “I’m going to fix my husband.”

I don’t know what he thought of the situation, but he almost ran down the hall. What had happened?

After three days of broiling himself in the hot sun, Jack—whose skin is sensitive anyway—had turned into a human lobster. He couldn’t even let a sheet touch his skin. The doctor had diagnosed it as first-degree burns. That’s why Jack had to spend the third night of our honeymoon in the bathtub, soaking himself in vinegar! Luckily, as I said before, this was no indication of our future lives together. From then on, I made sure that Jack was properly wrapped into towels or some other protective clothing whenever he planned to remain outside.

But once he recuperated, we had a wonderful time in Florida. And we’ve ha a wonderful time ever since.

Jack has so many outstanding qualities, it is hard to list them all. One of the most important is his ability to keep a level head, whether times are unusually good, or bad. And believe me, we’ve run the gamut—from the days when we lived on beans, to the high praise he has reaped for his performance as Ensign Pulver, in “Mister Roberts,” and other parts.

Amazingly enough, we experienced our hardest times—not in New York, after we got married—but shortly after we first came to California.

In New York, both our careers soon switched into high gear. We were then able to afford a very nice three-room apartment in an old brownstone house on 62nd Street. We had fireplaces in each room, looked out on a tree-lined street, enjoyed a homey, attractive living room. The only drawback was the closets, or what they called closets. Generously—or was he?—Jack gave me the smaller one because it was much deeper. “You can get more clothes into this one,” he explained. I did, too—by hanging them sideways and having to take out practically my whole wardrobe every time I wanted a dress from the back of it. Finally I decided it was easier to put some of them into boxes and push them underneath the bed.

But we had fun in New York, thanks to our careers, and a steadily growing circle of friends that prevented us from getting much sleep. But who cared?

When we moved to California—in spite of our high hopes after Jack’s first picture, “It Should Happen to You”—we went through some difficult months. Practically all our money had gone into the down payment for our house, and in between pictures, Jack didn’t earn a cent. And “in between” stretched to eight months.

We survived, mostly by improvisation. Such as doing all the chores around the house ourselves, and saving on anything else Jack thought he could do himself. And believe me, Jack thinks he can do anything!

For instance, after our furniture was unpacked, a pickup trash service wanted $15 to cart away the boxes and paper. “I’ll do it for half,” Jack proclaimed. He rented a trailer, brought it to the house, loaded it up, and took it out to the city dump. Total cost: $20.

Generally speaking, however, Jack has done an excellent job of keeping the home electrical system and plumbing in operation, and only in one respect has he failed—constantly, persistently, and stubbornly. Whenever he hangs up a picture or a mirror, he refuses to measure it ahead of time. “I can do it by eye-sight,” he always claims. Then he steps back five feet from the wall which is about to be ruined, squints at it a couple of seconds—and starts pounding. The first thing we did when we could afford it was to repaint and repaper the whole house. There were so many nailholes on the walls, they almost looked like a modern design. That didn’t go with our Cape Cod style house and semi-formal furnishings.

Actually, I learned about Jack’s stubbornness when he is convinced he can do something a few months after we married.

We have some very dear friends back East, Sam and Joanne (Jo for short) Ehre, who used to take us to auctions in New Jersey, where we bought most of our furnishings.

One Sunday, Jack and I had bid for, and gotten, a beautiful set of dishes which we planned to take back home. Sam gave the car keys to Jack, to load our dishes Into the trunk, while he, Jo and I went upstairs to look around some more. “You’ll have to back the car up toward the house,” Sam suggested, and then a bit worried, “Do you know how the hydromatic drive works?”

“Sure,” Jack assured him confidently.

Of course, he’d never handled it. But it looked easy enough for a child to manipulate.

A few minutes later, while absorbed in some wonderful antiques, I suddenly heard a tremendous crash. I knew what happened even before I rushed to the window: Jack had backed right into the furniture, and crushed half a dozen chairs!

As he looked out of the back window to survey the damage, he put his foot on the brakes, then slipped the gear into “neutral”—so he thought. The instant he took his foot off the brakes, the car shot forward—right into a whole pile of glassware, smashing it to smithereens.

The payoff came when, in spite of Jack’s insistence upon paying for the damage, the auctioneer refused to take a cent. “I’m an old friend of the Ehres’,” he insisted. “And besides, I haven’t laughed so hard since I was in the first grade!”

Then, to top it all, Sam let Jack drive the car back home. It took nerve on both their parts—and on Jo’s and mine, too. We were riding in the back seat.

For that matter, I have seen Jack’s nerves of steel in operation under much more serious circumstances.

About a year ago, after a visit to Hawaii, we were flying back to California. Just about the time we reached the point of no return—the halfway mark between Honolulu and the mainland—I noticed oil sputtering from one of the plane’s engines. For a couple of seconds, I was frozen with fear. Finally, I managed to tug on Jack’s sleeve. “Something’s wrong with the engine,” I whispered excitedly.

My husband thought this was a great joke. “You shouldn’t have read ‘The High and the Mighty,’ ” he chuckled.

“Honest, Jack. The engine’s losing oil!”

He still thought I was joking, but to play along with it, followed the direction of my pointing finger. “It’s probably nothing,” he said calmly. Nevertheless, he rang for the stewardess.

“My wife thinks we’ll have to ditch the plane just because the engine is losing a little bit of oil,” he laughingly told the stewardess. “Would you just look at it, please, and tell her she has nothing to worry about. . .”

The stewardess looked, turned pale, and without saying a word rushed up to the pilot’s compartment. Sixty seconds later, the flight engineer came to take a look.

“Will you please tell my wife she has nothing to worry about?” Jack repeated.

He too turned pale, and like the stewardess left for the front without a word of explanation. We went through the rest of the crew, including the captain, in the same manner. After seeing their expressions, Jack knew as well as I that we were in trouble. But he tried his hardest not to show it, in order to make me feel better. And I think if I hadn’t known him so well, he might have gotten away with it.

We made it all right—we even had enough fuel left for an emergency landing at Palmdale, since Los Angeles’ International Airport was fogged in.

Another quality of my husband’s which I grew to like is his complete honesty, and his refusal to take advantage of anyone. Like with the little foreign sports car he bought a few months after we moved to California.

At the time, Jack didn’t think we could afford a new car. (Later he found out we could have afforded it far more than the used one we got.) So he shopped around till he found an MG, “in top condition, with brand-new motor; all it needs is a little tightening of the brakes and the clutch”—according to the salesman.

Also, Jack was told that we didn’t have to pay cash for it, but could have most of it financed.

Never having bought anything on time, Jack neglected to read the small print, and didn’t discover until too late that the financing charges alone were running up to $400—and that was only the beginning.

When he brought the car home, he noticed that the front tire was a bit low. He decided to put on the spare but, when he opened the trunk, he found the spare had a hole big enough to shove his fist right through. And after closer inspection, he realized that the other four tires looked well only because they were newly lacquered, that there was hardly any rubber on them. Before the week was over, he had to buy a new set.

While he was at the garage Jack thought he’d better have the clutch and brakes adjusted.

“What brakes?” the mechanic asked. And then, “What clutch?”

Almost another hundred dollars went into the car. By now Jack paid more than if he’d gotten a new one in the first place. After getting the car into good shape, Jack drove it for almost a year, then sold it. The day after the sale, the rear end fell out of the car. My husband had no obligation to pay for it. But he did—in full. All $250 of it.

Just as admirable is the fact that Jack didn’t even lose his temper about it. As a matter of fact, he seldom ever does.

One trait of Jack’s which took a while for me to get used to, is his spur-of-the-moment behavior. When he gets something on his mind, it has to be done immediately—particularly vacations.

Thus, one night at a party in New York, when one of the guests glowingly described a fishing resort in Canada, Jack suddenly decided we could afford a few days off. So we promptly left for Ontario—at two in the morning.

“Are you sure you know where we’re going?” I asked him twenty-four hours later, as we bumped along on a winding, narrow, desolate dirt road.

There wasn’t a trace of doubt in Jack’s mind. “Of course I do.”

Later, we found out the road was made for jeeps only.

About three A.M., we saw a dim light in the distance. To get to it we had to cross a wobbly-looking bridge—a “walking bridge” we were told, after we had crossed it. When we finally pulled up in front of a little shack, Jack got out, walked to the front door, and banged on it.

There were heavy footsteps, then the door flew open and a bright flashlight glared in Jack’s face. He also saw a shotgun in the man’s arms. “Qu’est-ce que vous voulez?” the man burst out.

“Nous voulons. . .” Jack kept groping for words, but this was no time to recall his French. “Fish and Game Club,’ he finally managed.

“Oh, you are goeeng to zee Fish and Game Club,” the man said. “Down zee road. . .”

After we drove for what seemed |ike hours, I began to doubt we were even heading in the right direction. “You cont suppose the fellow at the party who told us about it just had too much to drink. . .”

“. . . and was making it all up? No! a chance.”

Just as my doubts reached the point of disillusionment, we saw the lodge. Ten we had to awaken the caretaker—who, of course, hadn’t expected us. The lodge turned out to be one of those really isolated places where you make reservations weeks in advance. Luckily, they had room for us. Actually, we were the only guests:

We weren’t as lucky last summer, when Jack suddenly decided we should go to the High Sierras.

He made up our mind, I packed, and we were ready to leave within less than half an hour. But when we arrived at Bishop, we couldn’t get any accommodations—and we had to sleep in the car. We picked an idyllic spot for our first night, right next to a lake. It was romantic, cold and uncomfortable.

About four in the morning, I had to get out of the car and stretch. Wrapped up in every stitch of clothing I had brought along, I was sitting in front of the car, one hand over the fire Jack had started, the other clutching a martini which we had wisely brought along in a thermos bottle. Jack went one step further. He had a martini in one hand, too, but instead of warming his other hand, he held on to a fishing pole! He didn’t want to waste a minute of our vacation! Needless to say, he didn’t catch anything. Even the fish must have been too cold to bite that early.

I have listed so much on the “credit” side for my husband that to balance the score a little, I’d better mention his one habit that leaves room for improvement: his forgetfulness. He can’t remember names, places, faces, to mail letters, pay bills. You name it and he forgets it.

At first, I used to be a little upset when he even forgot our anniversary. But seeing how badly he felt when I gave him a present, and he had nothing in return, I knew I was wrong. And he is so considerate when he does recall them!

On the first anniversary we celebrated in Los Angeles—which coincided with our lowest time, financially—Jack brought home a huge carton. I unwrapped and unwrapped and unwrapped, until I finally found a golf ball with a little note attached: “Happy Anniversary, from Jack.”

“How sweet,” I said as I handed it back to him.

I don’t play golf. Jack does.

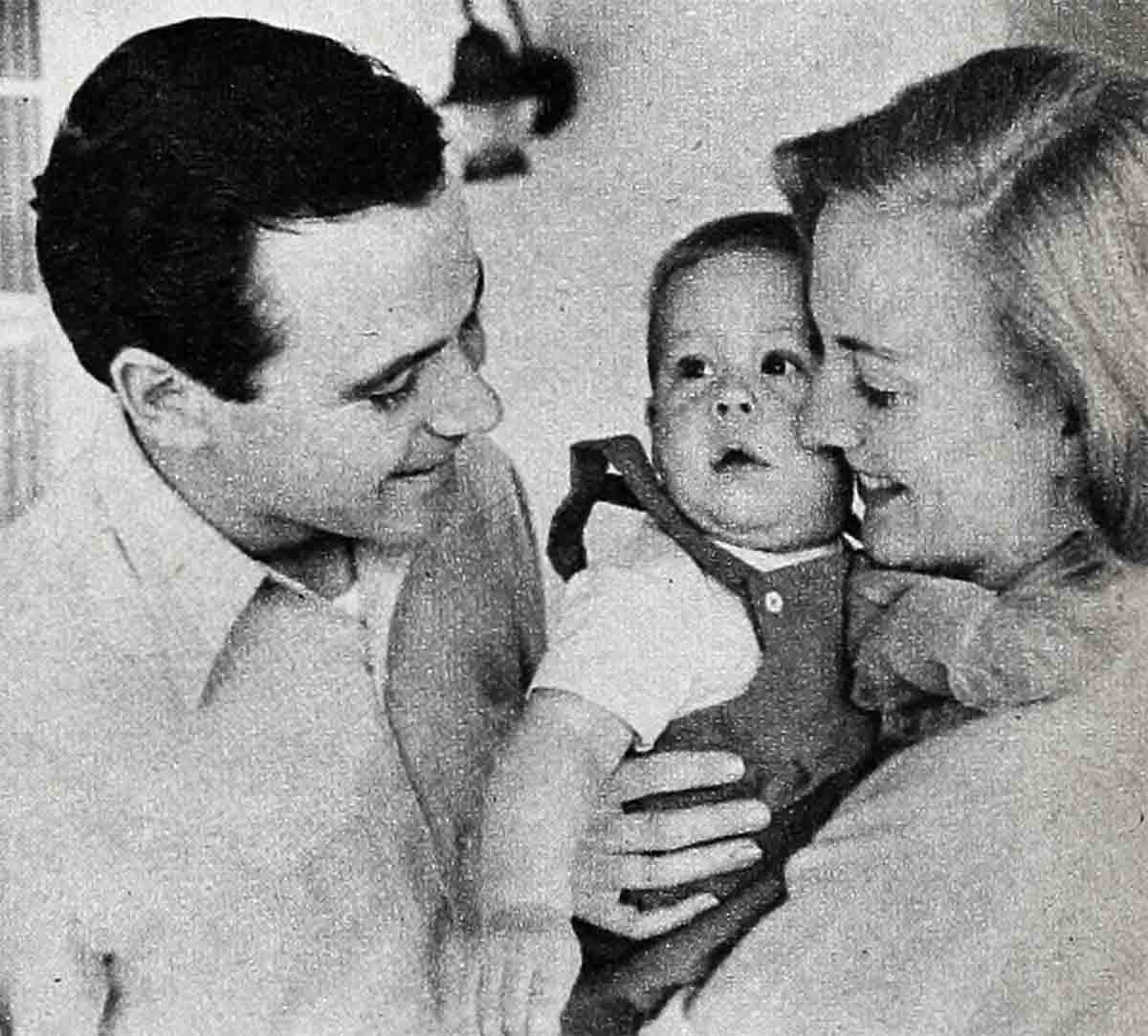

For our next anniversary, he gave me a music box that played Brahms’ lullaby, a baby brush and comb. We were expecting Chris at the time.

Of course, I didn’t mind. I’m happy Jack is so fond of being a father. In fact, he was so anxious, he wanted to put me into maternity clothes the day we found out we were expecting!

Nor has he changed in that respect. When Chris was born, Jack filled my hospital room with more toys for the baby than flowers for me! Since then, Jack has included the little fellow so completely in all our activities that Chris takes part in almost everything.

That’s the way I’ve always wanted our family life to be: happy, exciting, full of fun. And the credit for it all goes primarily to Jack. He’s a Lemmon all right—but the nicest, most wonderful kind in the world.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1956

No Comments