Will Hollywood Ever See Audrey Hepburn Again?

When Audrey Hepburn married Mel Ferrer, it was rumored all over Europe that she would become inaccessible.

“Ferrer is over-protective,” one observer noted. “It’s impossible to get to Audrey alone. Marriage and success will make her more remote.”

On their Italian honeymoon, Audrey and Mel did try to give the press the slip. “After all,” Audrey later explained, “a honeymoon is a private matter.” But once the honeymoon was finished, and Audrey took off for Holland and England, she was surprisingly available and down to earth.

In Amsterdam with her husband for the premiére of Sabrina, she insisted upon spending all her time raising money for the Dutch War Victims Fund.

In the department store where eight years ago she had worked as a $12-a-week salesgirl, Audrey put on a fashion show, modeling Givenchy outfits. She packed the house.

In the afternoons she visited Miss Soni Gaskell, the Dutch teacher who first taught her ballet. She called upon Jan Prins, a war hero she had known as a little girl in the town of Arnhem. She posed for hundreds of pictures, talked with dozens of young actresses and ballerinas. At the end of five days Audrey had raised 20,000 Guilders for the fund to construct a home for the war wounded. In The Hague she was awarded a gold medal for her charity work. And her countrymen, filled with pride at her behavior, told anyone who would listen that “Audrey Hepburn is the sweetest, kindest, most wonderful actress. And her husband is a fine man, too.”

When the Ferrers reached London where Audrey, six years ago, got her first theatrical job, newsmen were much more forward than they had been in Amsterdam.

Paramount staged a press conference for their star in the Dorchester Hotel. Audrey was bombarded with the most personal questions. Was it true that she was expecting a baby? “Not yet,” she answered. “But we want one badly.” (Ferrer has four children by previous marriages.)

“If and when a baby comes,” Audrey continued, “it will be the greatest thing in my life, greater even than my success. Every woman knows what a baby means.”

How about her marriage to Ferrer?

Big-eyed.Audrey smiled. “Three months have gone by and I have no regrets. What more can a girl ask?”

Did Audrey and Mel plan to work together a la Sir Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh?

“We played on the stage in Ondine, and we hope to play in the movie version which we plan to make in London. After that, we’ll see.”

Would Audrey consider giving up her career to devote all her time to being a wife and mother?

“That’s difficult to tell at this point. However, I doubt it.”

The room in the Dorchester where the press conference was held was much too small—Paramount later sent letters of apology—and reporters left it in a hurry. But not before they had thoroughly discussed how much—or how little—Audrey had changed in the past few years.

To those who had known her only since her success, she seemed infinitely changed—and not, as rumor had it, for the worse. She seemed friendlier, more relaxed, more genuinely self-confident and poised than they had ever known her. Marriage, they said, had done wonders for Audrey Hepburn. Who would have thought it?

As it happens, many people would have thought it. To them, Audrey has not exactly changed; she is merely her old self again, her real self, the person she was before fame, with its great demands upon her health, caused her to become tense, forced her to withdraw from people for a while.

What was Audrey like when she was still an unknown? Her years of war and terror as a child in Amsterdam have been hashed and re-hashed since Gigi and Roman Holiday, but what of her early acting days in London, the days that gave her her start, the days when she made the friends who still know her best?

One of these friends, Roger Railton-Jones, has the following story to tell—about an Audrey Hepburn who never has really been described before. Here it is, in the words of Mr. Jones.

One of my clearest memories of Audrey is of.a slim young girl at my side, fidgeting nervously as the house lights darkened in the projection room of the ABC studios at Elstree. A gasp of wonder escaped her and she leaned forward in her seat, her head cupped in her hands, her eyes fixed on the screen. “Oh, it’s all wrong,” I could hear her murmuring as she followed her own movements and gestures on the screen, in a poignant love scene with Nigel Patrick. Then the lights went up and Audrey Hepburn, who was seeing herself for the first time on the screen, turned to me and in a tear-choked voice cried, “Oh Roger, it’s awful! If only they would shoot that scene again. I did everything wrong. I don’t know if I’ll ever make an actress.”

Five years later, I was sitting on the edge of my seat as the curtains parted at Broadway’s 46th Street Theatre and Audrey Hepburn, now an accomplished artist, held me enraptured as the Ondine.

In the years between those two episodes Audrey Hepburn had shot to the summit of international stardom, to awards and applause and the acclaim of millions. And somewhere along the way she had acquired a reputation of being inaccessible for interviews and photographs, highhanded in her relations with her English studio, and near a breakup with her mother.

Could Audrey Hepburn really have changed from the charming and adorable young girl whom I knew at the beginning of her career? Has she really gone high-hat and temperamental? Or is she the victim of a too-rapid rise to fame, overwork and poor health?

The very first time I saw Audrey was at London’s Cambridge Theater in 1949. She was dancing in the chorus of a musical show, Sauce Piquante. She was just one of a line of girls, but even then her poise, charm and individuality made her stand out. I remember checking the program and finding her name there in tiny print.

About a year later the casting director of ABC studios called the ABC publicity office where I worked. “I’m sending a girl named Audrey Hepburn to see you,” he said. “The only thing she’s done in pictures is a bit part in Laughter In Paradise. I think she’s got tremendous possibilities and we’ve put her under contract. Talk to her and let me know what you think.”

Later that day I met her for the first time. Her name hadn’t clicked before, but as soon as she entered my office, I recognized her as the girl from the chorus line of Sauce Piquante. As she approached, I looked her over analytically—the way you learn to do in a film studio where glamour is a business. Her dancing training was evident from the graceful way she walked across the room. She introduced herself, and I noticed she had a strikingly melodious voice. But she had none of the obvious physical attributes for stardom. Her nose was too large, her mouth too wide, her teeth too crooked. She was too thin for her height; her legs were indifferent, and she was almost flat-chested. Yet there was something about this girl which made all these factors unimportant. She had a sort of wistful, child-like, pixie quality about her, combined with tremendous vivacity and sincere charm. Her eyes sparkled with the sheer joy of being alive. I liked her on sight and I couldn’t help admiring the clever way in which she disguised her physical shortcomings. Her heavy eye make-up concentrated attention on one of her best points, and her hair, which she wore the same way then as she does now, was an ideal complement to her piquant personality.

As we talked, and I learned a little about her background and personal history, I noticed a distinct reluctance to go into details about her hardships during the war. Later I learned what she had been through in occupied Holland, but all she would say then was: “I was hungry quite often.”

I was impressed by her quiet determination, almost bordering on ruthlessness, to succeed as an actress. The very terms of the contract she had negotiated with ABC were proof of her confidence in her own future, and her business acumen. It was an unusual contract. Audrey was to make a minimum of one picture a year, with the privilege of approving each script. It was extremely rare for an unknown artist to demand and receive such terms. This early faith in her own ability has been fully justified, for it is this clause in her English contract which now enables Audrey to reject any script she regards as unsuitable.

She had so magnetized me and I was so certain she had the makings of a star that I was already planning what I could do to help her on her way. As it happened, I needed one of our contract artists to make a personal appearance the following evening at a policemen’s annual ball. It was really quite an unimportant event. We had agreed to provide one of our starlets, as it was useful to be friendly with these particular police who patrolled the roads near the studio. When I asked Audrey if she’d do it, her first reaction was one of awe and fear. “Do you really think I’ll be able to?” she asked seriously. “I’ve never made a personal appearance before. What do I do? What do I say? What shall I wear?” I explained to her it was just a routine job. She would have to make a little speech, which I would write for her. Then she’d pose for a few pictures, and maybe dance a few times with the policemen.

“Do you think I should go out and buy a new dress?” she asked me anxiously. I laughed and assured her this was not a Royal Command Performance.

The next day Audrey phoned me about five times, with a host of unimportant questions. After I’d sent the speech to her apartment, she called back again with suggestions and changes. She was trembling with nervousness when I called to pick her up that evening. I told her to relax—that she was not going to Buckingham Palace, but to a plain, ordinary policemen’s ball.

This was my first opportunity to see the effect Audrey had on a group of men—and hardboiled ones at that. What I saw that evening convinced me that this girl possessed that rare and magical something which every great actress must have—“Star quality.” I saw it at the very outset of the evening. She lost all traces of nervousness and quickly had the men and their wives eating right out of her hand. As far as those policemen were concerned, Audrey Hepburn was already a star. In fact she is still the mascot of the Hendon Mobile Police group.

Thereafter, whenever we needed someone for personal appearances or publicity stunts, I’d call Audrey. She was by far the most cooperative actress our studio had, as well as the most likeable.

To this day, I can never eat a piece of turkey without remembering the day we spent together at a turkey farm getting some holiday pictures. The idea was to have Audrey in a cuddlesome pose with one of the creatures. Audrey showed up for our date, cute as a button in tartan slacks and a perky hat. It was a wet and dreary day, but we couldn’t postpone the session.

As we approached the farm, Audrey looked out the car window and saw the spreading carpet of mud in our path. She glanced ruefully down at her bright plaid slacks, gave a little sigh, but said nothing. But the worst was yet to come. These turkeys, who probably awaited a fate more serious than picture-taking, weren’t at all cooperative. Audrey joined in as we all—the farmer, the photographer and myself—tried to corner one of them. He fought and struggled and gobbled, but we finally managed to get one into Audrey’s arms.

We were all congratulating ourselves as the turkey seemed to be calming down for the picture. The photographer took aim, focused, when—bang—his flash bulb exploded almost in Audrey’s face. She didn’t flicker an eyelash, but the turkey, terrified by the flash, bolted. Audrey gave chase in the drizzle, finally caught him, and the pictures went on. We finished about three hours later.

From that day to this, Audrey refers to publicity shots as “turkey pictures.”

On meeting Audrey’s mother, Baroness Van Heemstra, I realized what a strong influence she must have had on the formation of her daughter’s character. Although there is little physical resemblance, Audrey has many of her mother’s characteristics—a strong will, unfailing courtesy and a gracious old-world manner. Audrey’s mother did more than anyone else in those early days to encourage her to become an actress. She also advised her as to the business and finance aspects of her career.

Audrey’s first speaking role at the studio was in a film to which I had been assigned, Young Wives Tale. This was in 1951. Despite the fact that hers was a minor role and the picture featured two of England’s greatest stars, Joan Greenwood and Nigel Patrick, Audrey finally got the lion’s share of the publicity. Newspaper people, coming on the set to do routine stories, recognized this girl as a striking new personality and a natural for stardom.

It was during the shooting of this film that I realized Audrey was a perfectionist in everything she does. She often complained about her looks, particularly her uneven teeth and her hands. She even disliked her own voice, although this is one of the most attractive things about her.

I told her once: “Audrey, you shouldn’t worry about these things. They are part of your charm. That’s what makes you different from all the others. Just stay exactly as you are and you can’t help reaching the top.” But Audrey was never satisfied with herself. She worked constantly to learn everything she could about acting. While other starlets from the studio were frequenting London’s night spots and clubs in the hopes of getting publicity, Audrey would spend her evenings taking ballet and singing lessons. She had little social life, but preferred to go to foreign films and sit through a picture two or three times to study acting technique.

Audrey’s salary at this time was small. She rode to the studio, located outside of London, by bus, and often brought sandwiches for lunch. Yet the apartment she shared with her mother, although tiny, was in the most exclusive part of London. On her limited income, she didn’t have much money to spend on clothes so she chose them with great care. Tight slacks hid her thin legs and high neck blouses covered her prominent shoulder bones. She wore flat shoes to cut her height.

Despite her physical and facial imperfections, Audrey was the favorite subject of the unit cameraman, who said to me: “This Hepburn girl is extraordinary. It’s impossible to take a bad shot of her.” The versatility of moods she could portray by simple facial expressions delighted the director, Henry Cass. And she had a great capacity for hard work, despite a physical frailty which is not only apparent but real—a result of malnutrition during the war.

It was not surprising that all the men on the set were enchanted by her, but amazingly enough women seemed to like her too. Several established female stars on the lot were known to dislike her because of the attention she had been getting, although they never had met. One of them, attending a studio party where Audrey was a guest, made several catty remarks about her to me. “Whatever has that girl got? Why she’s as thin as a rail, absolutely no sex appeal.” Right after this I purposely brought Audrey over and introduced her. Audrey immediately turned the conversation to the star’s current picture, asked her how it was going, complimented her on her past successes, and completely charmed her. Not once did she refer to herself or her career. When Audrey left us, the actress who had so recently been consumed by professional jealousy said to me, “Why, she’s delightful!”

Audrey did a few other films on and off the lot, including Lavender Hill Mob with Alec Guinness, but in none of them did she have a big role. She had often expressed a desire to make films abroad for she speaks several languages fluently and was raised on the continent. I was, therefore, not at all surprised when she phoned me one day and said excitedly, “I’ve accepted a part in a French movie called Monte Carlo Baby, with location on the French Riviera. Isn’t it exciting?”

Monte Carlo Baby was no epic, but it did prove to be the turning point in Audrey’s career. As everyone knows, it was during this picture that Audrey was seen one day by the late great French writer, Colette. Audrey later told me exactly how it happened: “We were doing a scene on the front steps of the Hotel de Paris. Colette was being wheeled through the front door when she looked over in my direction, stopped, and then slowly came towards me. I didn’t know who she was until she told me. ‘How would you like to play Gigi in New York?’ she asked me. I couldn’t believe that she was serious, but, of course, I answered, ‘Yes.’ ”

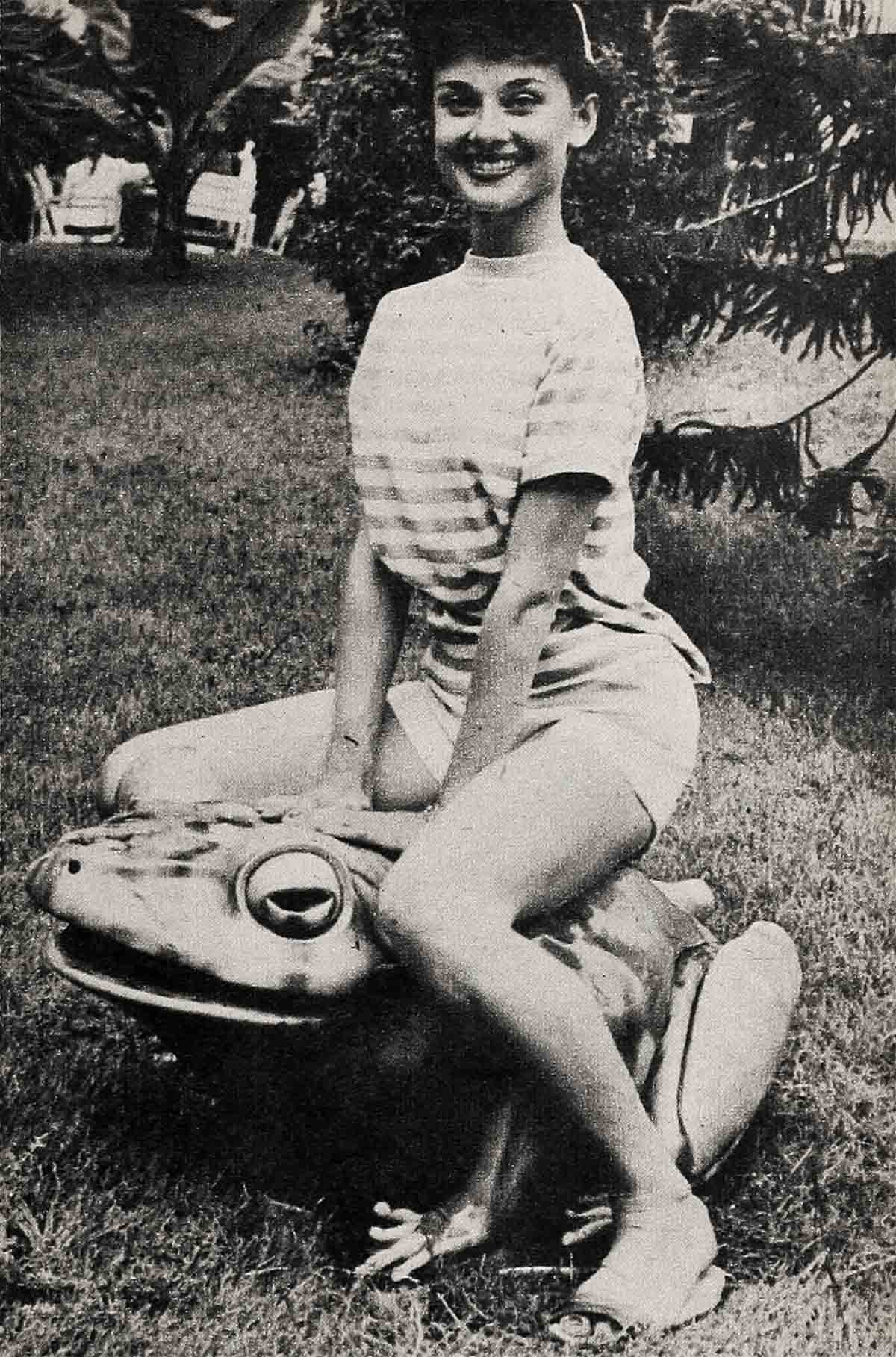

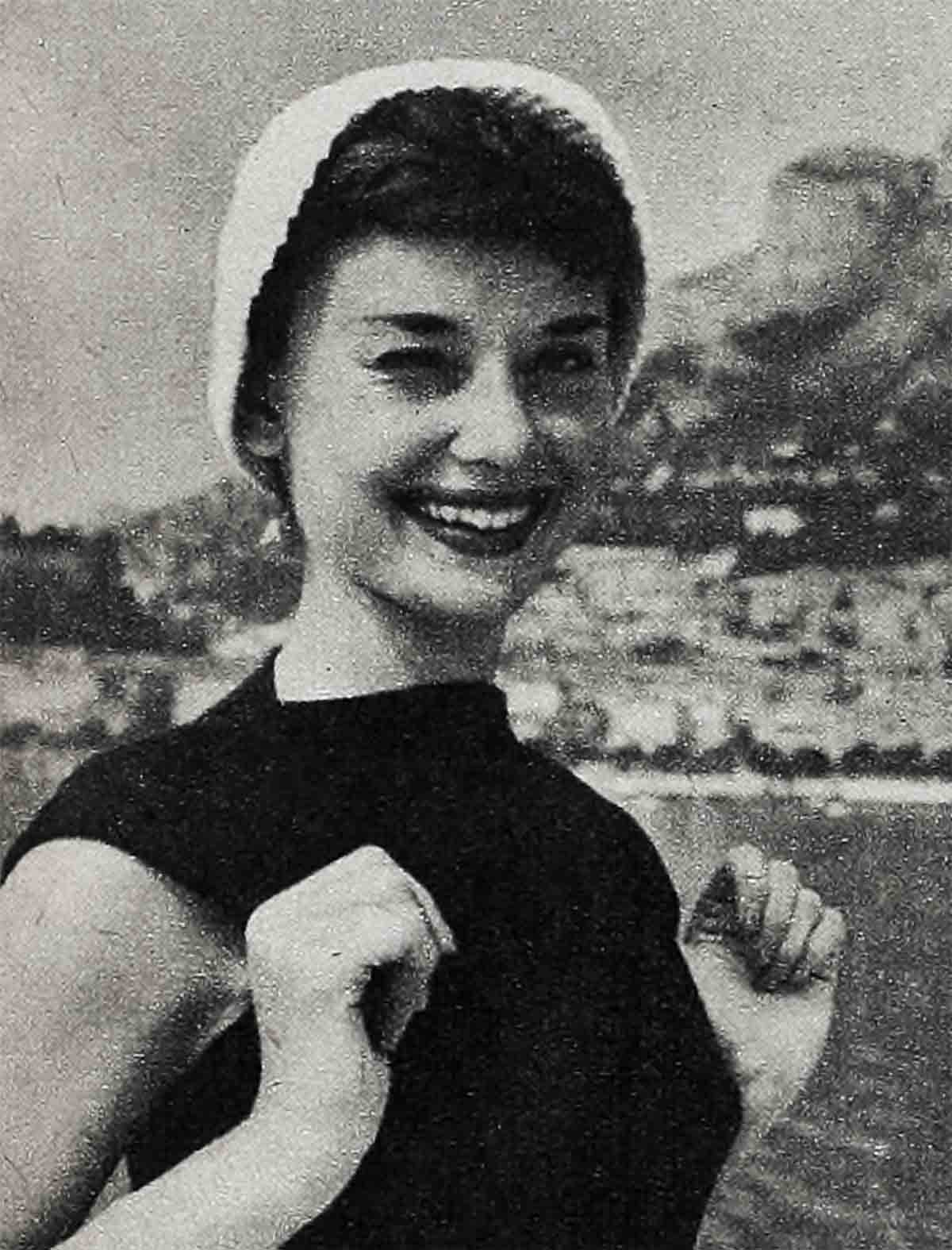

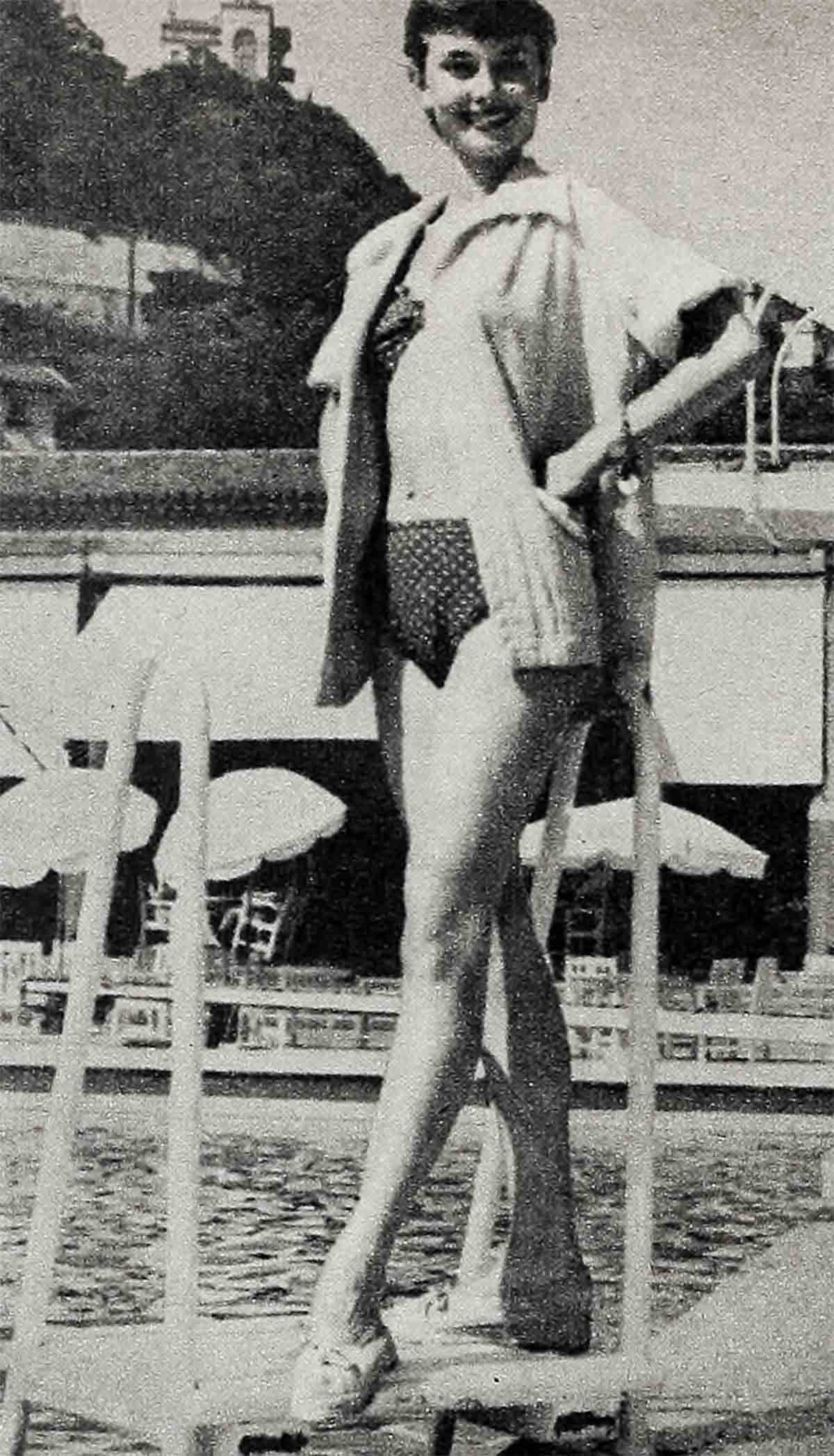

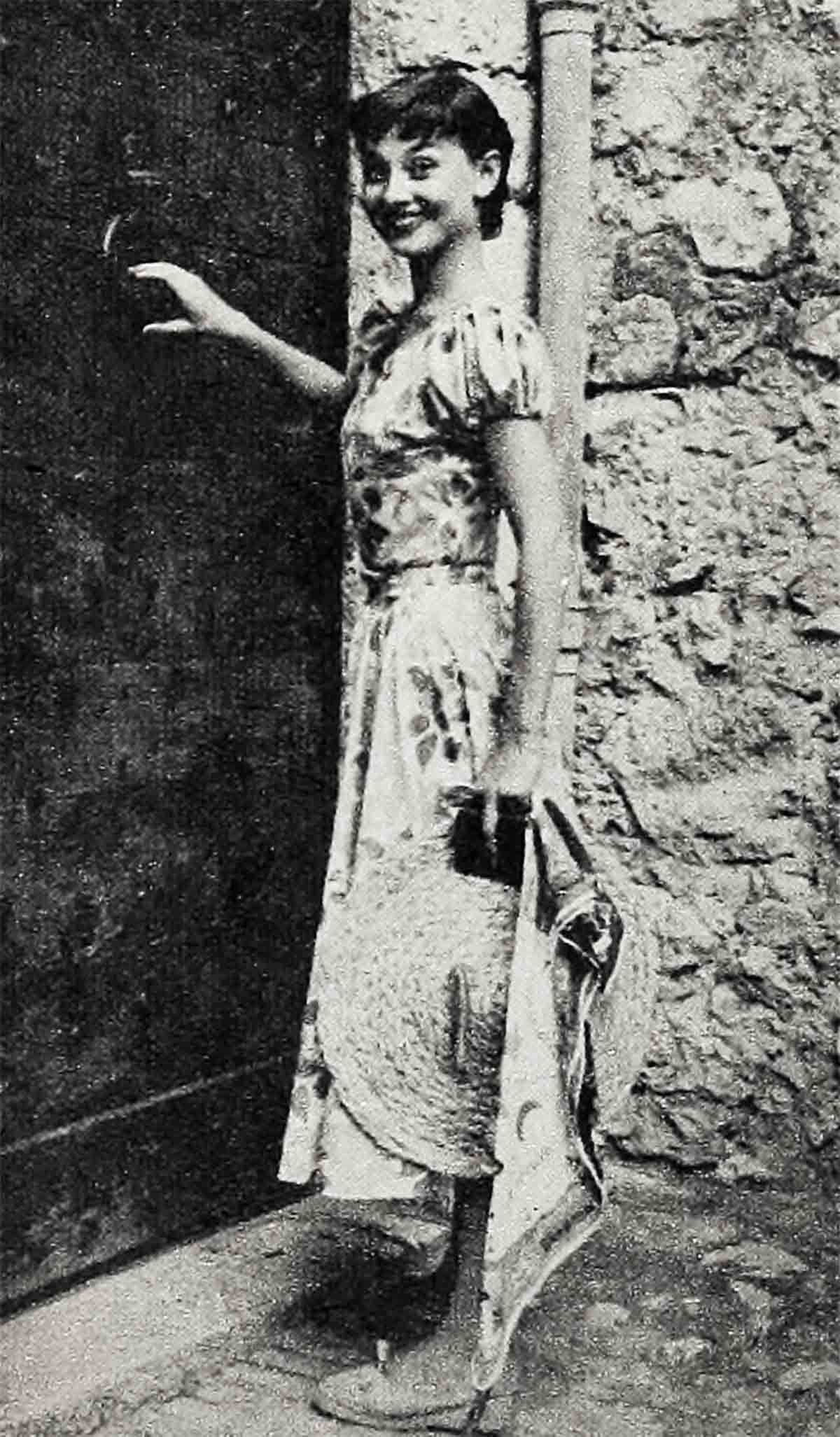

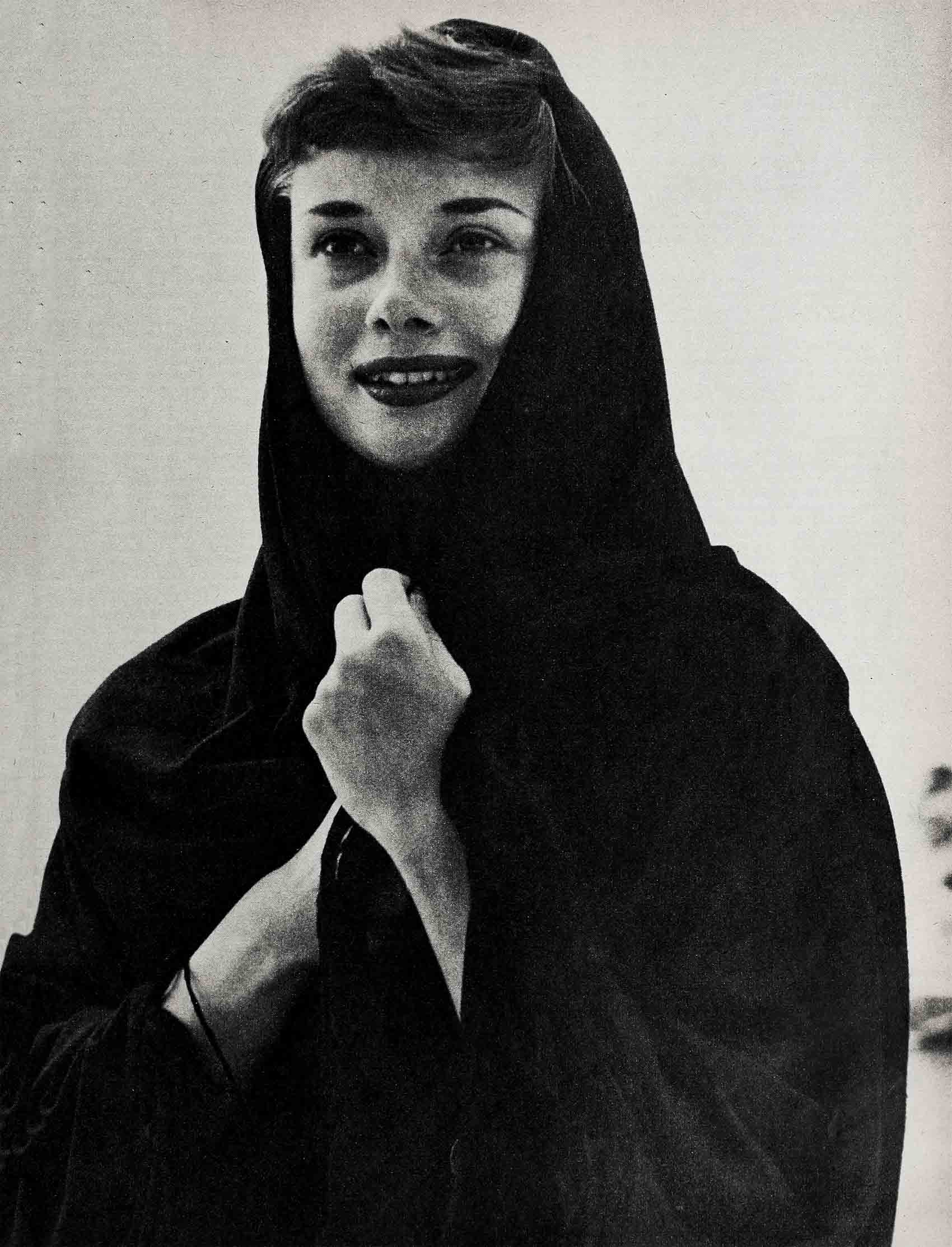

This Monte Carlo film, besides being an important landmark in Audrey’s career, is also a vital link in our story, for it was then that these pictures of Audrey were taken. A friend of mine, Edward Quinn, an Irish photographer working on the Riviera, was on location doing routine press shots of the cast. As he later explained it to me, he’d never even heard of Audrey Hepburn.

“Part of the cast was rehearsing a scene in the Sporting Club of the Casino,” Ed told me, “and I was shooting pictures right and left. Then I saw this girl. She was in a corner of the room discussing a step with one of the dancers. I was absolutely floored by her. She stood out like an orchid in a patch of weeds. I grabbed one of the crew and asked, ‘Who is this girl?’ I learned that far from being the star of the picture, she had just a small part. I introduced myself and asked her if she would pose for some pictures. She agreed.”

Quinn picked her up at the appointed time in his old pre-war Renault two-seater. On the way to a neighboring village, his car broke down. “I was very embarrassed,” Quinn said. “Here we were on a mountain road with very few garages and little traffic. It meant I had to fix the ear myself. Audrey couldn’t have been nicer about the whole thing. In fact, she offered to help, but I didn’t want her to get dirty, so she sat on the running board and kept up a gay line of chatter while I worked.”

As these pictures show, Audrey was more than cooperative in posing for Quinn’s camera. During several photographic sessions, she changed costumes many times and never complained about moving from one locale to another.

A few days later she called Quinn and in a calm and controlled voice said to him, “Paramount Pictures in New York have asked me for some photos of myself. I’d like to send the ones you’ve taken. May I?” Quinn, of course, agreed. Audrey was signed by Paramount soon after. These pictures, herewith published for the first time, are from that set.

I saw Audrey again when she returned from Monte Carlo, all set for Gigi and with a Paramount contract in her pocket. She was the happiest girl alive, but she still retained a humility and gratitude for the wonderful things that were happening to her.

“I know I’m going to love America,” she told me, “but I’m nervous about appearing on Broadway.” Even as Audrey said this, I could detect in her manner a deep underlying confidence in her own ability which I knew would see her through. As theatrical history has recorded, this self-assurance of hers was fully justified.

After she had finished the run of Gigi and the filming of Roman Holiday, Audrey arrived in England for a brief visit. I had been following her meteoric career with interest, and I was curious to know if her success had changed her. But she was still wide-eyed with wonder at her success.

That was the last I saw of Audrey until I reached New York myself a couple of years later. On my arrival, I wrote her a short note and mailed it to her New York hotel. Audrey tried twice to reach me on the phone, without success, so she wrote me a letter telling me she was leaving for Hollywood for the filming of Sabrina. It was a warm, friendly letter, full of reminiscences about the studio in England, including a reminder of the day we took those turkey pictures. It showed that Audrey, who had now reached the summit of international stardom, could still take time to remember her old friends.

It was after she had finished Sabrina and was in the midst of rehearsals for Ondine that the first faint notes of criticism about her began to appear in the press. Writers complained that it was impossible to get an interview with her, and that this was proof of an inflated ego. The same familiar photographs of Audrey in black matador pants and a high-necked blouse appeared time and time again in papers and magazines—simply because there were no others available. All this made me wonder if in the brief period since her letter to me, Audrey could have undergone such a transformation. I was determined to find out. I wanted to see Audrey again—and I wanted to see her play. So I booked seats for Ondine.

I hadn’t warned Audrey about my coming that evening. Arriving at the theatre, I handed a note for Audrey to the stage door attendant, telling her I would come backstage after the performance.

After all the adverse publicity I had been reading about her, I was anticipating some difficulty. I had none. She had left instructions with the stage door attendant to conduct me to her dressingroom, and she was standing outside the door waiting for me. Throwing her arms around my neck, she kissed me affectionately. We were both near tears.

The first excited rush of questions and reminiscences over, Audrey beckoned me to a chair and asked eagerly: “What did you think of the play? Did you have good seats? I tried to contact you in the theatre to change them in case you didn’t.” As I discussed her performance, Audrey seated herself on the floor in front of me and proceeded to take off her make-up. I was studying her face closely. It was not until the last traces of her heavy, grotesque make-up had disappeared that I was able to see how she had changed physically. Months of overwork and strain had left their mark. She was a tired, tired girl.

I felt I knew her well enough to question her about the strains affecting her health and looks. “Yes, you’re right,” she said, “I am working too hard. As a matter of fact, my doctor has told me that unless I cut out ail interviews, photo sessions, public appearances and other outside activities, I’ll have to leave the play and go into a sanitarium.” Audrey got up from the floor where she’d been sitting, put her hands into the pockets of her dressing gown and paced nervously up and down the room. “I really am exhausted. I’d like to do everything the press boys ask me, but I just can’t.”

That for me was sufficient explanation for her alleged lack of cooperation. I could see this was no act. Audrey was a very sick girl. But tired as she was, she still greeted with a smile a group of teenagers from her fan club.

This was about the time when stories were circulating in New York about Audrey and Mel Ferrer. I hesitated to ask her about him, for she had always been sensitive about discussing the men in her life. Up to now, Audrey had had but two serious romances that I knew about. The first was with Marcel Lebon, a handsome young French singer and dancer, whom she was dating when I first met her. I saw them together often and I believe Audrey was very much in love with him, but her interest in him terminated about the time! she came to New York to appear in Gigi. Her second big romance, with Jimmy Hanson, a wealthy young English playboy, almost ended in marriage.

Audrey mentioned Mel Ferrer’s name only once during our conversation. “He’s such a wonderful actor,” she said quietly, “but his part in this play—it’s too small. He has no opportunity to show what he can do.” Then she began to talk about the! vacation she was planning. “I’m going to Switzerland for a complete rest,” she told me. “I shall stay in one of those little wooden chalets, miles from anywhere, and I’m going to sleep and sleep as long as I want to, and catch up on all the books I haven’t had time to read.” Her eyes sparkled with the old animation as she described her plans for the first real vacation she’d allowed herself in years.

A few weeks later I called at her apartment and drove out with her to Idlewild airport. On the way, she told me how relieved she was that Ondine had closed.

“I just couldn’t have kept going much longer doing eight performances a week,” she said. She was obviously thrilled about the prospect of returning to the continent. “I love America, of course, and I always shall,” she remarked, “but I don’t really want to live in any one place permanently. That’s why I love acting. It takes you to so many different places.”

At the airport, I put Audrey on the, Swiss Airliner which was to carry her across the seas to a most important occasion in her life, her marriage to Mel Ferrer. If Audrey knew that day she was soon, to be a bride, she gave no indication of it.

The news of her marriage a few weeks later started a whole train of thoughts and doubts in my mind. From mutual friends, I learned that Audrey’s mother had disapproved of her association with Ferrer right from the start, and that this had caused several bitter arguments between them. Baroness Van Heemstra was herself the victim of an unhappy marriage, and obviously didn’t want the same to happen to Audrey. The Baroness is a practical woman and she must have been disconcerted by Ferrer’s three-marriage record.

That’s where Mr. Railton-Jones’ story ends. The rest is speculation.

If Audrey’s marriage is as successful as she claims, what does the future hold? Actresses with far greater reserves of physical stamina and fewer demands upon their time and energy, have cracked under the strain of combining a career with marriage and a family. Audrey wants a baby, wants to act. Even with the support of her husband, added responsibilities may take a dangerous toll of her health. Possibly she, may limit herself to one picture a year, or devote herself almost entirely to stage work, though that would seem to be even, more enervating. Very possibly she and Mel may remain overseas for a long time, looking for escape from the publicity that follows them. But if her friends are worried, Audrey herself doesn’t seem to be. In London she and her husband attended the premiére of The Bridges At Toko-Ri, and someone asked the radiant Audrey how it felt to be a star. She smiled and cocked her head to one side. “Like Cinderella,” she said. She sounded very much as though! she had found both her prince and her happy-ever-after.

THE END

—BY ELLEN JOHNSON

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE APRIL 1955