The Men You Love To Hate

Ever since Warner Oland menaced Pearl White ’way back in silent days, movie villains, in their own dastardly way, have gone right on titillating female hearts. True, there’s been a change. The good old silent-screen boys with hearts so black were just plain mean. It was nothing for one of them to casually blow up the hero—or even the heroine—with a stick of dynamite and suavely twirl the ends of a sleek, black mustache at the same time.

But Jimmy Cagney kind of changed all that. Jim sauntered onto the screen, boyish and brash, and in no time at all was the hero of every boy who’d never really have the nerve to push a grapefruit in the face of a girl like Mae Clarke, and the heartthrob of every girl who wished she had a beau tough-minded enough to do it. It was 1931 and the film was “Public Enemy,” and Jimmy ushered into being a new kind of villain called the gangster. Cynical, unethical, a woman-beater at heart, the gangster-villain had even more female appeal than the black-caped menace of earlier days.

In 1936 Humphrey Bogart joined the mob (which already included George Raft, whose sleek, steely bodyguard role in “Scarface” brought fan letters from thousands, including Al Capone himself) and shot his way through “The Petrified Forest.” He had learned well from the dean of gangsterdom—Edward G. Robinson—who blazed across the depression-day screen as Little Caesar and gave unforgettable power and authority to the villain image. Bogie brought sex appeal to that authority.

Recently something’s happened to the villain. The term “juvenile delinquent” has taken hold. It isn’t right nowadays to merely sit in the audience and be scared to death by strong-arm boys. Now, you have to understand them. After all, these boys were misunderstood. They had confused childhoods. They weren’t responsible. Undoubtedly all true, but it’s made the screen villain a whole lot harder to cope with.

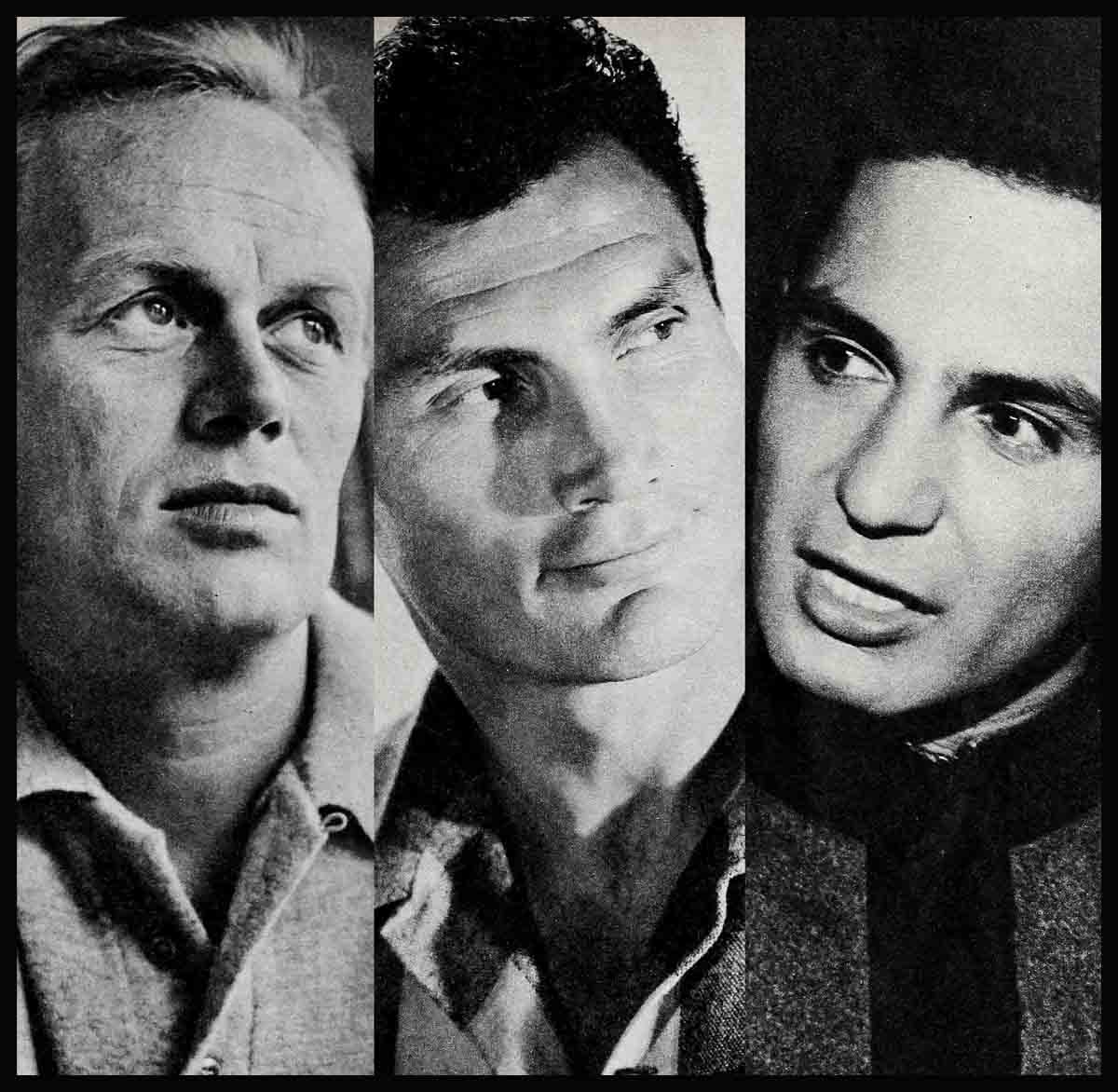

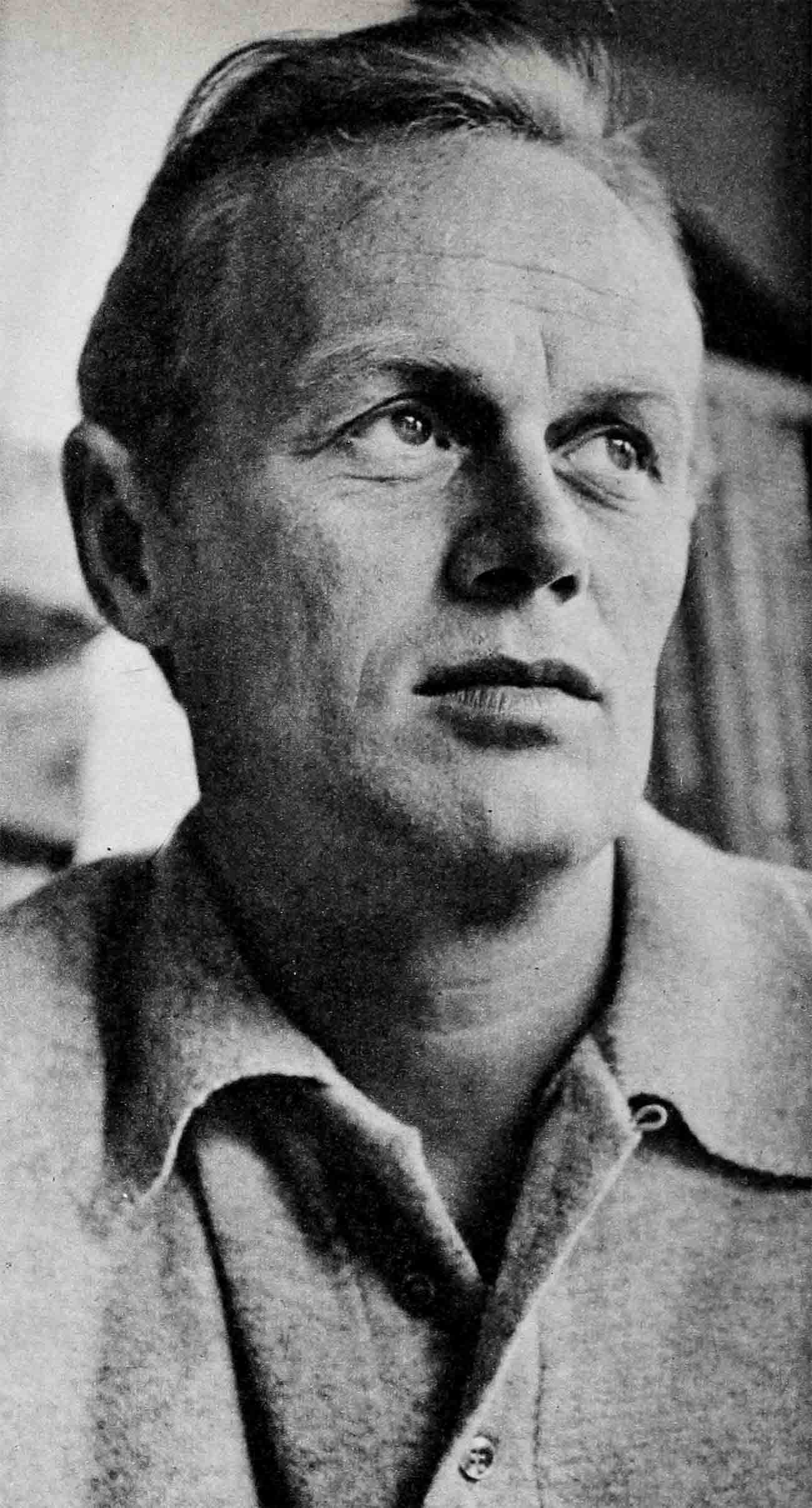

Today, there are only a few hold-outs in the old tradition. A small handful of men brave enough to play out-and-out black villains. Even Richard Widmark has gone straight. “Kiss of Death” had him push a little old lady (of course she was sweet) down a flight of steps to her death. The picture made him a guy you love to hate. But in Dick’s case you didn’t have to feel guilty about hating him. He never dragged in a mixed-up childhood.

“I liked playing villains,’ said Richard Widmark; looking mild and tweedy. “Good guys are gray types—wishy-washy and easily forgotten if they’re not done just right. But a good villain (and he emphasizes the ‘good’) is all black and can’t help but get a response from the audience.”

But now he usually plays heroes. How did he account for that?

“For one thing, I don’t want to be typecast. For another, a hero can be as interesting as a villain—if what people found intriguing in the menace can be carried over into the good guy—the personality traits.

“But every once in a while I like to go back to being bad. There’s always money in it, and besides, it’s probably good for both me and the audience.

“I mean petty annoyances build up in everybody’s life—a tiff with the boss, missing the five-fifteen train, the fuses blow out at home—you know. So finally you get mad—I get mad. I take out my nastiness by playing a bad guy. And maybe, in a way, you can take it out on me when you see me.”

Did this have any effect on his home life or his family? He laughed, “I don’t think so. My little girl saw ‘Kiss of Death’ recently on television and I don’t think she was frightened.” He paused and looked a little sheepish. “The truth is, I think she thought I was a little bit ridiculous.

“I play a good guy in ‘Time Limit’ which came out recently. I produced it myself.”

(It just goes to show there’s a little bit of good in the worst of us.)

Did he ever think when he was growing up in Sunrise, Minnesota, that he’d end up this way?

“In spite of the fact that some people seem to think I’ve always been a villain I was once a speech instructor at Lake Forest University in Illinois. Then I decided it might be more fun to act than teach it. I came to New York and went into radio.”

The stage finally lured Dick away from radio and he played his first Broadway role as a juvenile in “Kiss and Tell.” What followed were five prestige flops (no villains), but in one he caught the attention of director Henry Hathaway, who thought he might have the makings of a killer in spite of the fact—as one appraiser put it—he appeared all together “too well-bred, too intellectual and too upperclass.”

Well, Dick went on to prove—there’s nothing wrong with a well-bred, intellectual, upper-class villain.

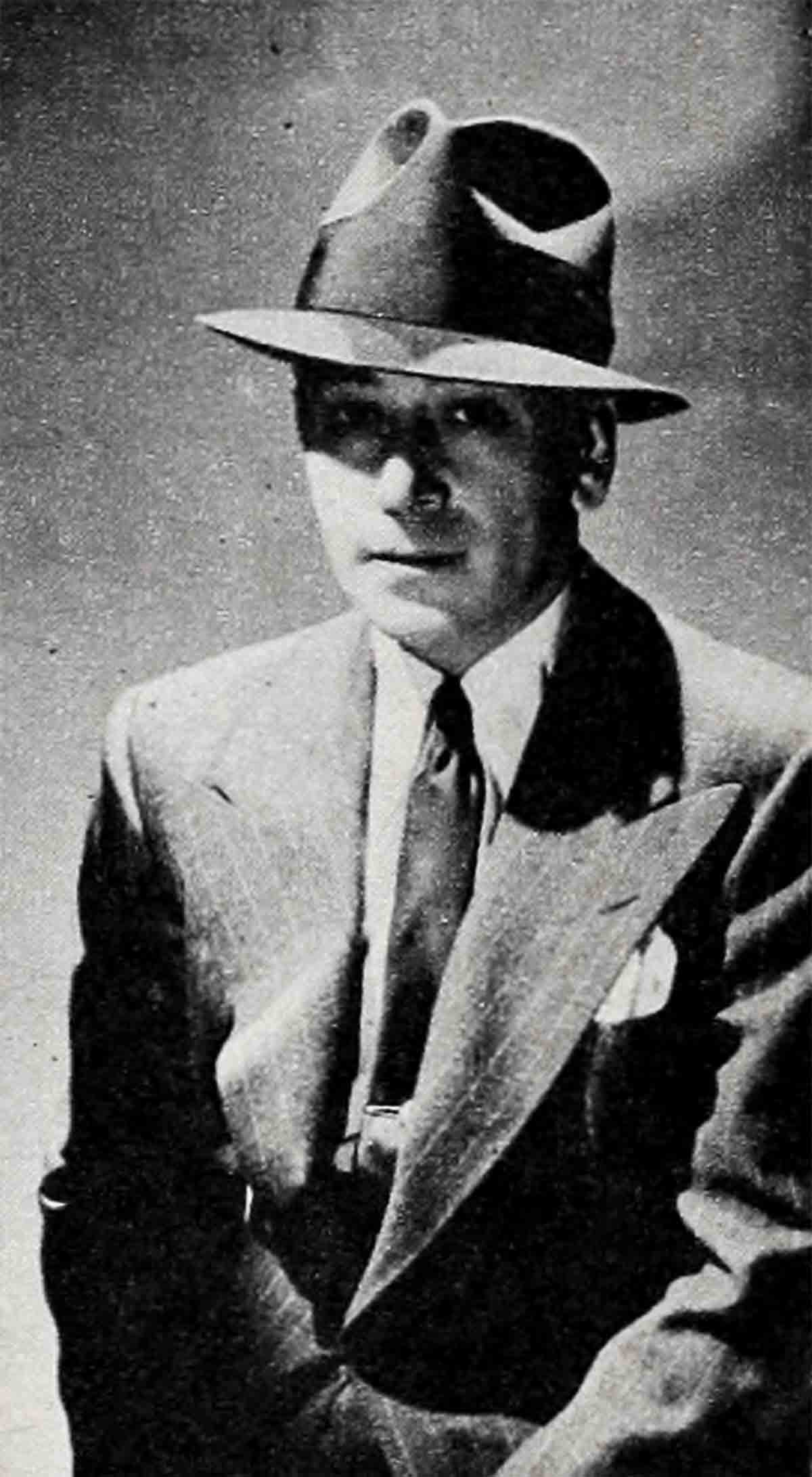

Did there ever breathe a villain more villainous than Jack Palance? We’d like to think not. Jack’s been killing pretty steadily ever since his first role as the psychopathic murderer in “Panic in the Streets.” Bringing the black villain back into vogue in “Shane,” he scared the living daylights out of kids and “caused three women in Chicago to faint,” as he went out after Alan Ladd dressed in black from head to toe.

In one unforgettable scene, where he was stalking Alan for the final kill, he created unbearable tension by slowly, carefully drawing on a pair of black kid gloves. The tension mounted and so did female casualties.

“I invented that bit myself,” he says, rather pleased. “I wanted to convey the feeling that this killer loves to kill. It is a sacred ritual with him and he approaches it with the same delight another man would a love scene.”

Panther-like movements, coldly chiseled features, and a soft, low voice, added to an air of sinister cunning, have made Jack, moviewise, the master of visual vileness.

Fascinated by philosophy, art and literature (he almost became a newspaper reporter), he grew up in Lattimer, Pennsylvania, a joyless mining town where he worked as a coal miner summers during college. A college football player and professional boxer (“I lost only two of my twenty fights”), he was almost kayoed for good during World War II when the bomber he was piloting crashed in Hawaii and burst into flames. His skull was crushed in and his face badly burned. “It seemed then like a bad beginning for a career in the theater,” a career which really got under way after Jack left Stanford University and understudied Anthony Quinn in Broadway’s “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

Not through with playing villains by a long shot, Jack says he had the unique opportunity of rubbing himself out in his latest film, M-G-M’s “House of Numbers.” “I played both roles—an escaped convict and the convict’s good brother. I killed my brother, which was really myself—see?”

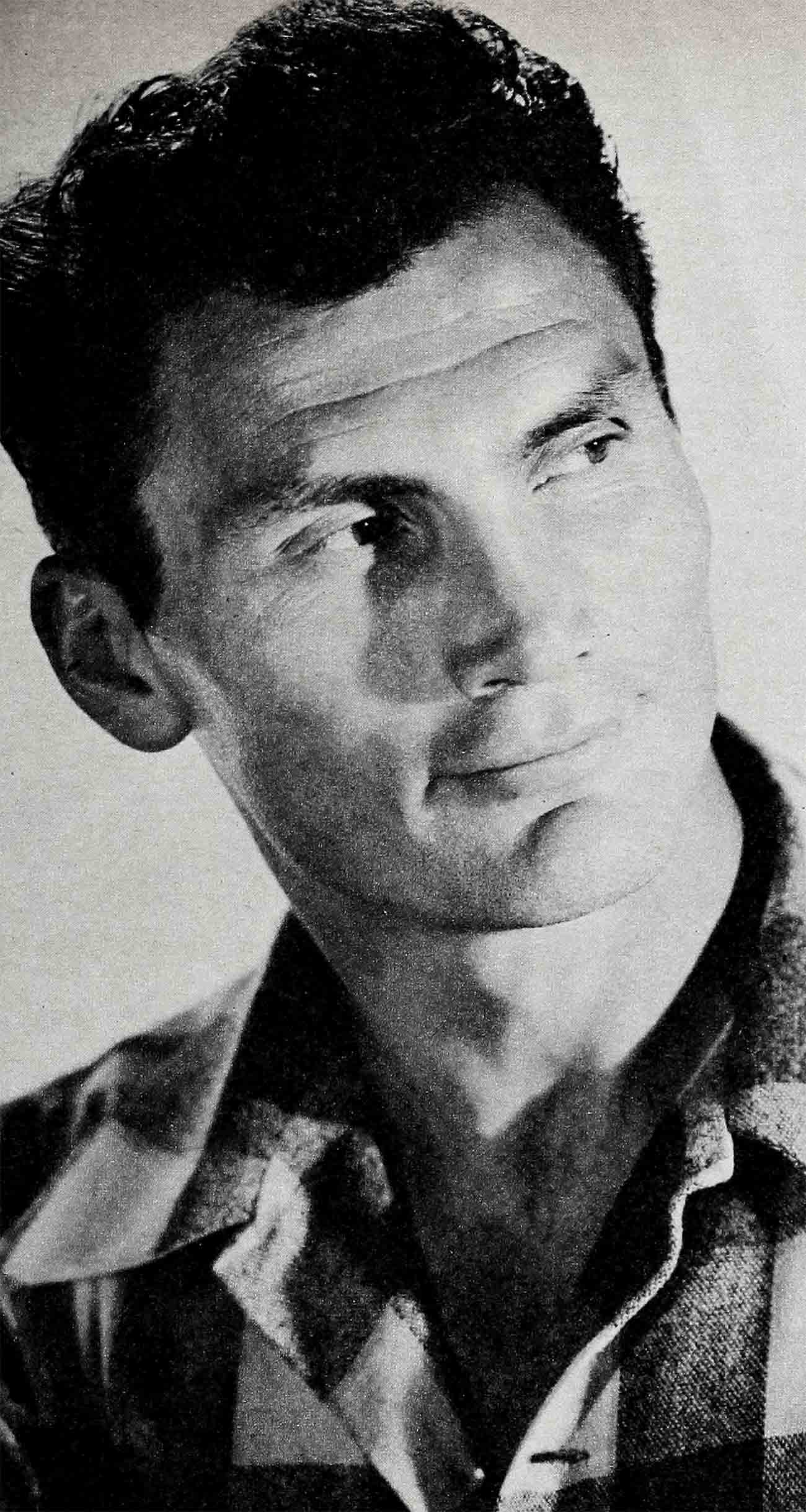

Ernest Borgnine, along with Dick Widmark and Jack Palance, has probably done more the past couple of years to revive the villain of old in all his blackheartedness and vile charm than any other group.

Ernest was about to apply for a holiday job with the New York City Post Office when his agent called to spread the glad tidings that Hollywood wanted him pronto for the part of Fatso in “From Here to Eternity.” He told his wife: “Rhoda, honey, I’ve got to go out there and be the meanest so-and-so in the world. If I make it, I’ll stay in show business. If I don’t, I’ll get some kind of regular job.”

Ernest made it. It’d been years since the public had seen anything so low. After seeing “Eternity,” even an uncle in Italy wrote Ernest a stinging note.

“He couldn’t understand,” Ernie says, “how the little boy he used to dandle on his knee could turn into such a beast as to beat poor, helpless Frank Sinatra to death. It’s perfectly simple,” I told him. “I’m a completely normal monster.”

However, the particular brand of pop-eyed, sneering malevolence that Ernie’s uncle disliked so much was just what the fans wanted. They shrieked with satisfied horror when he mauled Spencer Tracy in “Bad Day at Black Rock.” They winced with pain when he lunged a pitchfork into the back of a bank robber in “Violent Saturday.” And there’s more evil to come from Ernie. In U.A.’s “The Vikings,” he’s called upon to assassinate a British king, ravish the queen and generally make himself thoroughly unpopular.

“It took ten awfully hard years to reach that Academy Award for ‘Marty,’ ” (strangely, a sympathetic part), he says today. “And before that I spent the first part of my adult life in the Navy. It never occurred to me to even think of acting as a serious post-service career.”

But after he left, he was standing in line one day to get his GI unemployment benefits when he was asked what kind of job he wanted. His mind went blank, so he opened his mouth and said “actor.” It was as simple as that—a villain was born.

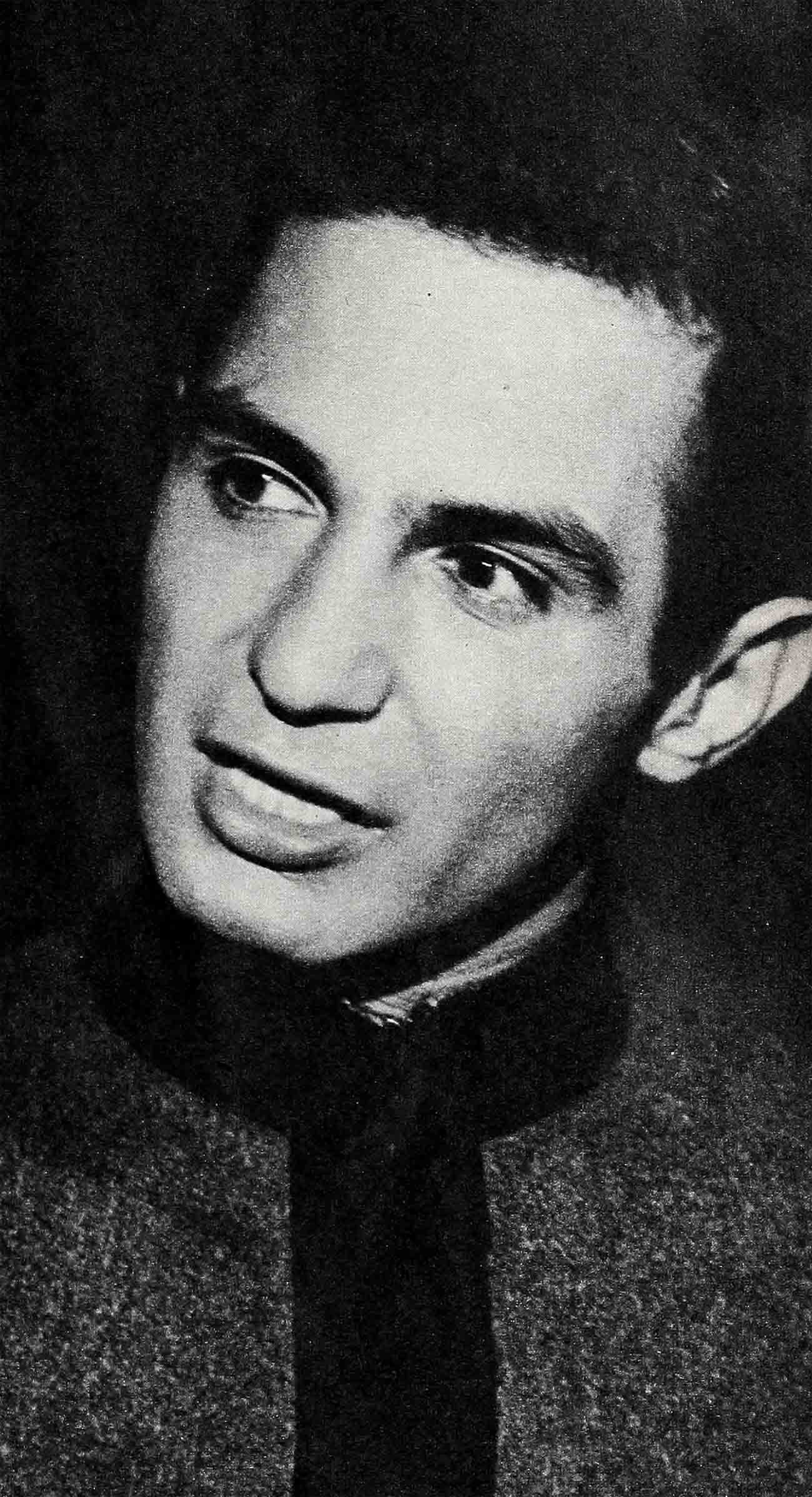

One of the nastiest menaces to come along was Ben Gazzara in “The Strange One.” A sort of small-time Machiavelli in a southern military academy, he very nearly destroyed the teaching staff and student body before he got his well-earned comeuppance in the picture’s dramatic climax. Female fans were left breathless.

Ben’s particular type of bad boy is plenty different from the mustachio-twirling heavy of the old days. Would he go along with the theory that many of today’s villains are sick rather than bad?

“Definitely, I’d say,” answered Ben. “At least within my experience. I’ve been a mixed-up character in the three major roles I’ve played: the dope addict in Broadway’s ‘Hatful of Rain,’ the neurotic husband in the play ‘Cat on a Hot Tin Roof’ and, of course, Jocko in ‘The Strange One.’ Or,” he laughed, “maybe you could say I played gray villains. If there is such a thing.” (One writer called him a “huggable heavy!”)

Twenty-six-year-old Ben lives in an unmovie-starrish fourth-floor walk-up apartment in the Seventies, right off New York’s Central Park. “Only forty blocks from where I grew up.” Like any other East Side kid, he played stick-ball, dodged cars and outran trucks; he still bears the scars from street fights and sidewalk accidents. But he loves New York. “I’d never want to live any place else, permanently.”

A far cry from the sadistic Jocko, Ben is pleased with the way his villainous movie role has aided his career. He loves acting: “I had acted in school plays when I was a kid, but my real incentive later was seeing that remarkable woman Laurette Taylor in ‘The Glass Menagerie.’ That did it. ‘This is where I want to be,’ I told myself.” Other advantages: He’s making a tidy income from movie wickedness and this gives him the opportunity, at last, to make life easier for his mother, who once worked in a garment factory for three dollars a week to help support him. “My mother’s pleased I turned into a rat,” he comments.

“I’d like to play a romantic type—once,” said villainous Rod Steiger recently. “I know that I’m not the conventional romantic type, but I’d like to give it a try just to see what happens.

“I guess the truth is I just like any part that’s exciting. If it turns out to be a villain, that’s okay with me.” Some of Rod’s best parts have been the latter: cruel Judd in “Oklahoma!”, the gangster brother of Marlon Brando in “On the Waterfront” (for which he was nominated for an Academy Award), the crooked fight manager in “The Harder They Fall” and the just-no-good dictatorial movie producer in “The Big Knife.” Soon you will see him in “Cry Terror.”

“I think,” he went on, “there’s a certain identification the audience has with the villain—right up to the time he commits the crime. And,” he added, “I also think moviegoers get a feeling of relief from watching a badman blow off steam.” He took a gulp of coffee.

“We used to drink this stuff by the gallon in the Navy,” he said reminiscently. He joined up when he was sixteen and for the next five years went down to the sea in ships. “I think I was the worst sailor they ever had. There was nothing I could do right. I even succeeded in getting myself jammed into a torpedo tube once. I’m sure they were relieved when I left and went into Civil Service.” He sighed thoughtfully.

Wasn’t that when he first got involved in the theater?

“Uh-huh. I started acting because I liked girls. The place I worked had an acting group, mostly girls. It seemed like a fine way to jog up my social life. But I never realized I’d get interested in acting.”

From such small beginnings are great things built. Little parts on Broadway, big ones on television followed, including the original TV Marty, then on to a life of crime in the movies. To sum up, what did he think of villains? Had they changed through the years?

“The traditional villain has changed, I feel. He isn’t consciously evil any more, but more sick and mixed up.”

Like his recent part of Carl Schaffner in “Across the Bridge”?

“Yes, and in a sense, that particular type is more a character part than a villain’s part. Carl is very rich and powerful in the beginning of the story, and he’s obsessed by the need to remain the figure he has created—the colossus of capital. But he hasn’t any wife, any love in his life. His greed is only an outward sign of his need to be reminded that he is the most important man in the world. And he tries to keep this image alive by making his own world, since he neither likes nor fits into the world around him.”

“Is he a villain?”

Rod shrugged his shoulders. “Guess you’d have to say yes. A psychological one.”

Only some, not all villains succeed when they go soft. For instance, Dan Duryea, who has been labeled everything from a “heel with sex appeal” to Hollywood’s “most no-account guy,” recently decided to mend his ways. He wiped off the leering grin, stopped sniveling, combed his hair, smiled prettily at the camera, and stepped out into millions of living rooms as TV’s “China Smith,” a hard-boiled, but upstanding, adventure figure. He was greeted with generous acclaim from critics and viewers alike, and Dan was secretly pleased that he had been able to cross over from heel to hero so easily and successfully.

That is, until four weeks later when Dan stopped by the studio mail department to pick up his fan mail.

As was his custom, he had brought along a suitcase. Dan was handed a thin batch of letters that wouldn’t have filled a shoe box—most of them from women who wailed, “What have you gone and done? We love you as a heel.”

Dan took the hint. He climbed back into his rumpled clothes, brushed up on how to slap a dame or knife a man in the back and was generally credited as being just as nasty as ever. Housewives once again took pen in hand and wrote, “Keep on slugging us, Dan. We love it!”

Dan had no intention of being either an actor or a villain. After college he became a successful advertising executive and might have become a Madison Avenue type hadn’t an illness forced him to seek a less nerve-racking career.

He decided to give the theater a try. From that moment on he never had to worry about a job.

Dan, who has been just as mean as he could be (on the screen, of course) ever since, has some interesting ideas on what makes movie heels appealing.

“Women are drawn to heels,” he said thoughtfully, “because heels make it very clear that the man dominates the woman. When a girl tries to fight the attraction she feels for the no-good guy who puts her in her place, who keeps her in doubt and suspense, she’s fighting her basic femininity. At the beginning of any romance, it’s not the gentleman who wins the girl. It’s the ruthless conqueror, the man who demonstrates male aggressiveness and dominance.”

In that case, we say, Long Live the Villain.

THE END

—BY M. O’DONNELL

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1958

No Comments