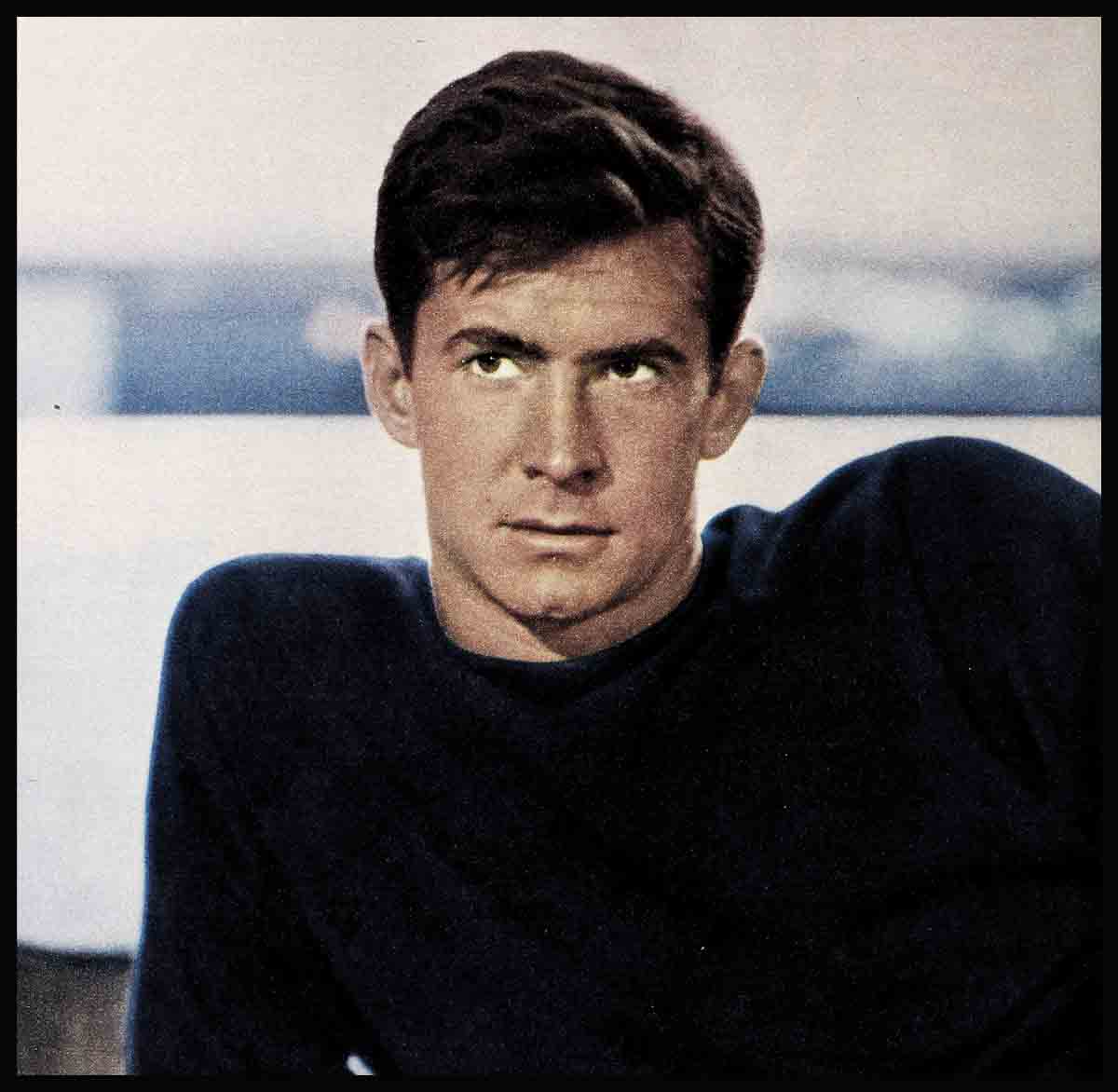

You’d Take Him Home To Mother—Tony Perkins

He’s a six-foot-two study in contrasts. There’s a quality of shyness about him, but it’s blended with an air of quiet confidence. His expression is generally grave. Yet it can be replaced at any moment by a friendly, slightly lopsided grin. He’s parlayed a childhood ambition to act into a blazing career on stage, television and screen. Obviously, he’s a competent, well-organized young man. Yet, when he pushes the commissary menu aside and explains, “On a picture I eat only steak and celery and peanuts,” you want to take him home so Mother can hover over him with meat, potatoes and spinach and insist on second helpings of apple pie.

That’s Tony Perkins.

One day recently, a Paramount soundstage was dark except for a cluster of lights beating down upon a small set in the center. It represented the interior of a Western shack. Three players sat at the table silently eating breakfast. “They’re rehearsing a scene for ‘The Lonely Man,’ ” a guide explained to a group of visitors.

Two of the actors were veteran scene-stealers Jack Palance and Robert Middleton. Still, it was the third actor who commanded the attention of those who watched. He had no dialogue, but it made no difference. Reminiscent of a stern, young Montgomery Clift, his thin, sensitive face was tense with inner conflict. No words were needed to tell you that he was close to heartbreak—and somehow you had the feeling that when it came, your own heart would break a little too. He was that kind of actor. “Who is he?” A teen-ager voiced the question for the rest of the onlookers.

“Perkins,” whispered the guide. “New boy. Plays Jack’s son in the picture.”

A pretty blond moved into the scene with a fresh supply of hotcakes. The young man waved them away, carefully avoiding so much as a glance at the girl. “Tony’s in love with her, but she’s his father’s girl,” said the guide.

“She’s out of her mind,” murmured the teenager. “Script or no script!”

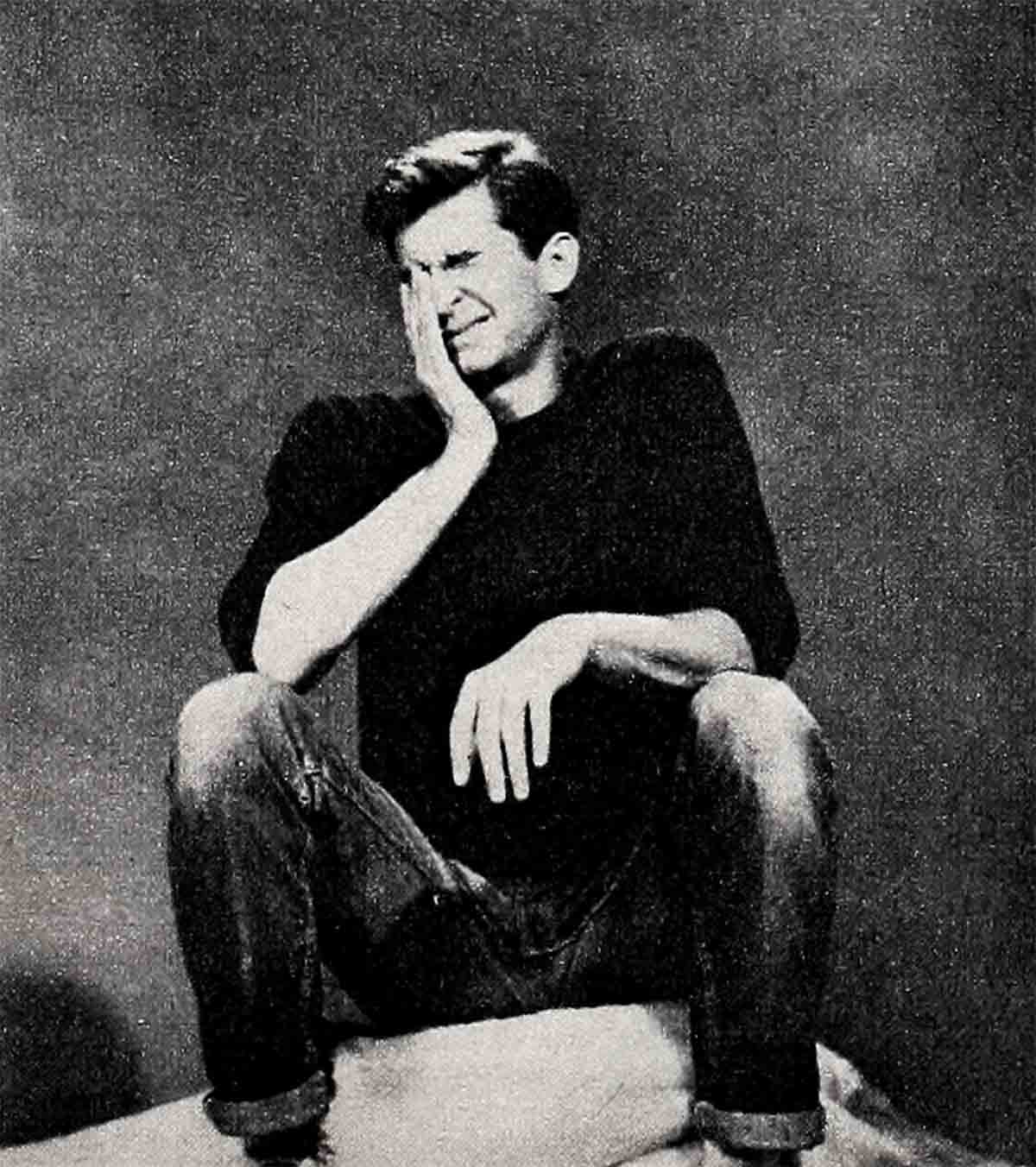

When the director stopped the action to give instructions to the actress, the young man’s audience was still a captive one. They watched as if compelled to wait for a clue that would separate the real Tony Perkins from the make-believe.

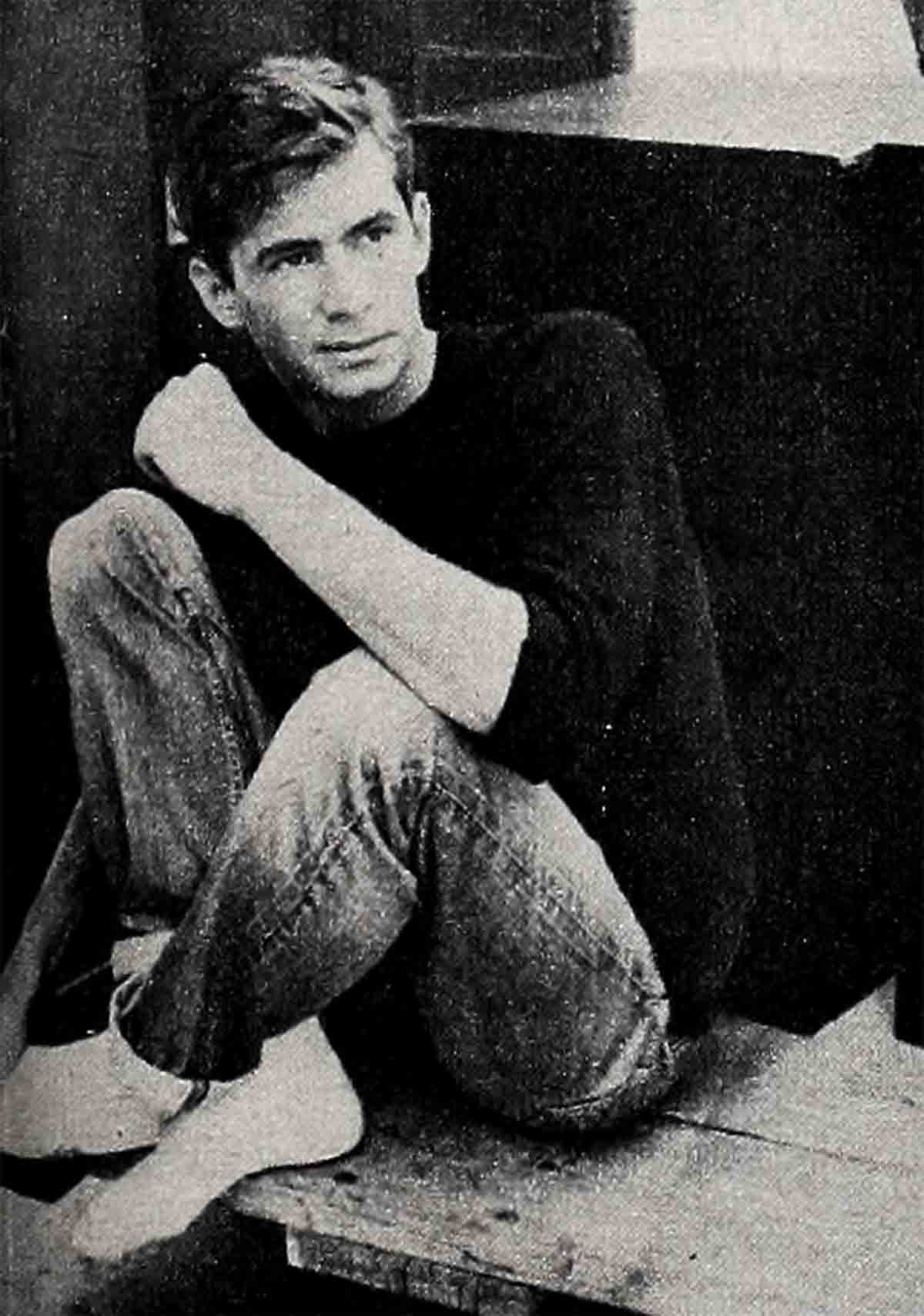

He slouched in his chair, stretching his long legs under the table. But his expression remained unchanged, his mood unbroken. Obviously he was a brooding fellow by nature.

He faced the director attentively, until he suddenly became aware of the spectators. But a brief, sweeping glance wasn’t enough for him. His solemn eyes surveyed each of them, and his look was the penetrating kind. For all his brooding, he seemed to miss nothing.

Then, as he caught the eye of the company hairdresser, the intense young man winked one solemn eye. If he’d stepped into a corner to stand on his head, he couldn’t have shattered the spell more completely.

For everyone on that drafty sound stage, there was no questioning the future of Tony Perkins. Within the space of a few wordless minutes he had managed to touch the emotions of an informal audience, win the loyalty of a teen-aged stranger, arouse the curiosity of a set full of visitors—and, having lulled the entire group into a serious mood, jolt them out of it with a wink. It is safe to say that, given a few hours on the screen, Tony will become one of Hollywood’s biggest stars.

You have to watch him, off the set, as well as on. Today, when there’s a tendency to place every newcomer in a category—such as brooder, individualist, rebel, shy-type, cut-up, great lover—Tony defies classification. Approximately one second after you’re certain you have him pegged, you find yourself reconsidering.

During a dramatic scene, he can tear your heart out. Then he’s apt to amble away from the cameras, grin the lopsided grin and remark, “I’d like to do a comedy. Maybe a musical. You know, I never played any of these complicated, tragic young men until I got into television. . . .”

At this stage of the game, he might well be expected to be totally preoccupied with Tony Perkins and his motion-picture career. But his inquisitive nature makes it impossible. As one of the Paramount publicists can testify. . . .

What the publicist had in mind one day was obtaining vital statistics for a studio biography. With pen and notebook in hand, she cornered Tony in the commissary. “My mother’s Janet Perkins, non-professional,” Tony began obligingly. “My father was Osgood Perkins, actor. I don’t remember much about him. He died when I was five. I was born in New York, April 4, 1932.”

As she wrote, Tony leaned closer. She looked up to find his nose a scant few inches from the top of her pen. “Shorthand. . . .” he said, in the tone that most people use when discovering uranium.

Many questions later, having exhausted the publicist’s knowledge of the history, uses and theory of shorthand, Tony slouched in his chair. “I’d give you the name of the hospital,” he said thoughtfully. “But it’s been torn down.”

“What hospital?”

“Where I was born.”

Oh, yes, vital-statistics-wise, Tony proved the soul of cooperation. But in the course of the afternoon she followed him around to get the statistics, the publicist also learned about the beauty of Lone Pine, the considerable acting talent of Walter Abel, how to pitch baseball, the weather in Florida, the merits of Chinese restaurants, and what was new with a fellow named Jug Smith. Jug’s name came up at the two-man college reunion which occurred on the steps of the soundstage when an old school chum happened along.

As the publicist has since said, “It’s better to approach Tony Perkins with a rested mind, if you plan to follow his.”

It is also helpful to expect the unexpected. While many newcomers take great pains to think up unusual items that will make the columns, the Perkins contributions come as refreshing afterthoughts. Unaccustomed as he is to publicity, he’s like a babe in the woods. “I’ve gotten good breaks in my career,” he once told a columnist. “But otherwise nothing very unusual happens.”

There was no doubting that Tony believed it. “I meet a lot of interesting people on my way to work,” he went on, trying hard to please.

Then, in answer to a raised eyebrow, he casually explained, “I hitchhike.”

“You what?” Until that moment the columnist had been under the impression that she’d heard everything.

Star or no, each morning Tony trudges down the hill from his apartment-hotel, crosses Sunset Boulevard and stands on a convenient corner. Within minutes, he has himself a ride—and invariably his deadpan sense of humor comes into play. Primarily because drivers always follow the same pattern of questioning. It began on his first morning in Hollywood when a low-slung convertible stopped for him.

Surveying the deceptively youthful face and the lanky blue-jeaned figure, the driver inquired, “On your way to school?”

“No,” replied Tony. “I work.”

“Oh . . . where?”

“In movies.”

“And just what do you do in movies?”

Tony mulled the matter and was struck with sudden inspiration. “I’m a stand-in,” he said. “For Tony Perkins.”

“Hmmmm . . .” said the driver. “Don’t believe I’ve ever heard of him.”

“That’s what I figured,” grinned Tony. “But you’ll be hearing a lot about Perkins,” predicted Perkins. “He’s a new actor who’s really going places.”

When they’ve seen “Friendly Persuasion” and “The Lonely Man,” Tony’s benefactors will know that they got the tip straight from the actor’s mouth. “But I guess I’m going to have to stop saying things like that,” says Tony.

Although he’s going places—and in a hurry—he’s never in too much of a rush to lend a helping hand. On the Paramount lot, he’s apt to be seen lugging anything from a potted plant to an armful of books—depending upon whom he’s run into and under which load they were staggering at the time. In fact, the word’s been spread among the studio secretaries that it isn’t even necessary to stagger.

On his way to lunch one day, Tony fell into step with an industrious girl trying to turn the pages of a book and juggle a large handbag. “Let me take that,” he volunteered and reached for the handbag before she could reply.

He swung it easily as they walked along. “I don’t read as much as I ought to,” he said, rather apologetically. “Just don’t seem to have the time any more.”

Then he thoughtfully lapsed into silence so that she could concentrate on the book. “Well, anyway, I tried to concentrate on the book,” the girl remarked as she related the story later.

As far as the ladies are concerned, Tony is like the boy next door who grew up to be a prize. And when he dates a girl, she may be sure that she’s the one and only. “I’ve gone steady with almost every girl I’ve dated,” he says. “I’ve never played the field.”

Then comes the grin. “One contributing reason may be that I’m a lousy dancer. It takes me about five months to get used to dancing with a girl.”

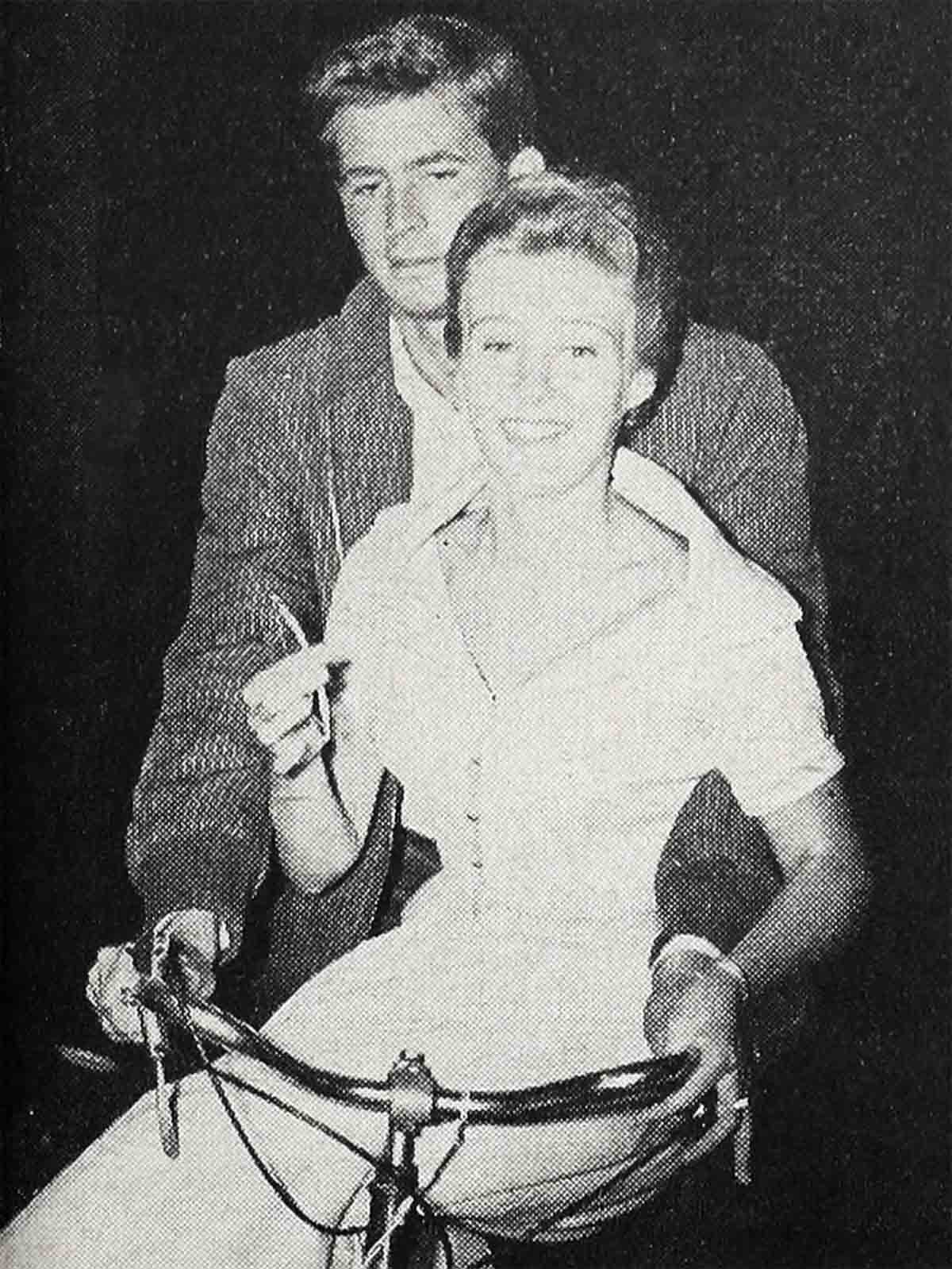

Tony’s steady date while making “The Lonely Man” was another New Yorker, Elaine Aiken. She’s the pretty blond—and she’s very much in her right mind. On one of their first dates, Elaine discovered Tony’s enthusiasm for Chinese restaurants. “It’s an uncomplicated Chinese restaurant,” Tony assured her en route. “So they tell me.”

Once seated, they scanned the menu. “Chop suey,” said Tony.

The waiter frowned. “Chow mein,” he said.

Having ordered to the waiter’s satisfaction, they held their appetites hopefully in abeyance for a while. Then for another while. Tony caught sight of the waiter and ventured to inquire when the first course might be arriving. The waiter consulted his watch. “It’s ten o’clock,” he said, and went away again.

“This is an uncomplicated Chinese restaurant?” said Elaine.

“It’s just that we’ve run into a complicated waiter,” Tony consoled her.

If Tony has learned to accept life’s little setbacks in stride, it’s because he’s had practice. Fired with the ambition to become an actor at a very early age, he considered schooling one such setback. Friends claim that he was probably persuaded to attend when someone pointed out that it was the quickest way to learn to read lines. Tony admits, “There were the school plays. I guess I wouldn’t have gone to school if I couldn’t have been in school plays.”

In compliance with his mother’s wish and his own good judgment, he wound up with quite an education. It began in a small private school in New York and ended at Columbia University. In between, he attended junior high school in Brookline, Massachusetts, the Browne and Nichols prep school in Cambridge, and Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida.

Career setbacks—and they seemed great ones at the time—he learned to accept philosophically. His first part was a rather minor one, that of an Easter egg in the second row. “But I found out that there were all sorts of things you could do with an Easter egg role,” Tony grins.

He was fourteen when he signed for his first season in summer stock. “It was 1947,” he recalls. “At that time, summer theatres were having to start all over again after the war, and they were finding it hard to locate apprentices. They began sending representatives to schools to recruit people.”

A stock company in Vermont offered him twenty-five dollars a week and Tony accepted, with boyish visions of being discovered. The visions dimmed a bit when the stage manager announced, “Perkins, you can pull the curtain.”

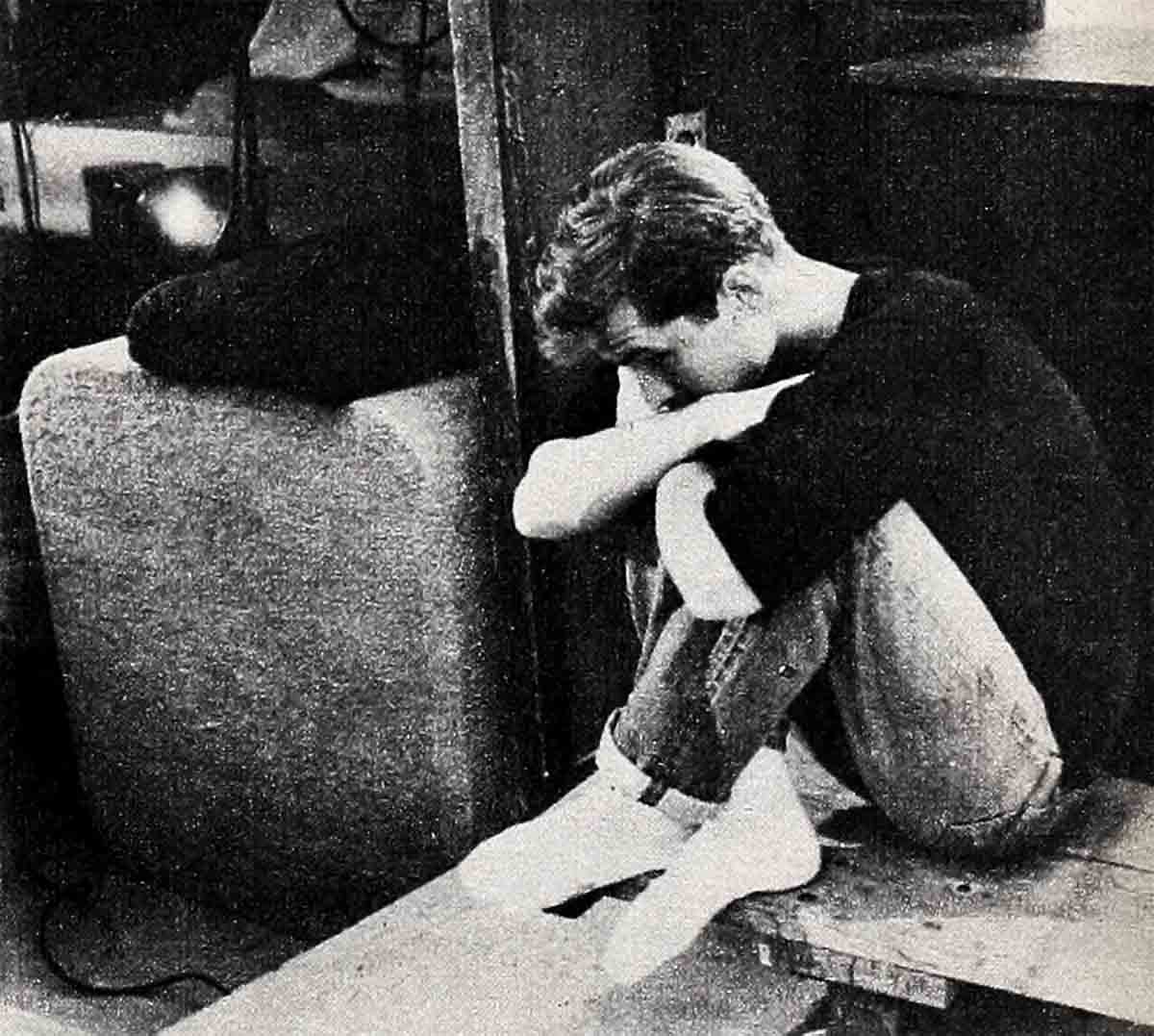

He also helped gather props, paint scenery, strike old sets, and put up new ones. A first glimpse of the scenery shop might have discouraged a less dedicated young man. The shop was underground. “Seemed about sixty feet under,” he remembers. “Like a coal mine. We’d get up for air once a day, have lunch and then go back to the dungeon. But I was fascinated by the whole business.”

One day they handed Tony a role in “Junior Miss.” He was to play a character named Haskel Cummings, the leading lady’s first date. But small as it was, the part meant that Tony would at last be treading the boards in a professional capacity. At least that was what both he and the director had in mind. First, however, he had a taste of near-catastrophe.

Beneath the stage there happened to be a passageway which led to the rear of the theatre. On opening night, Tony ventured back to watch the performance while awaiting his cue. He leaned against the back wall and became engrossed in the action. When the doorbell rang on-stage his first thought was, “Now who could that be?”

Then it came to him that it was supposed to be Tony Perkins, alias Haskel Cummings. “It was one of those experiences that stop you cold,” he says. “Time really stood still when I heard that doorbell.”

Breathless as he was when he reached the stage, Haskel gave a creditable performance. As the season progressed, Tony was assigned other roles. “I was usually somebody’s little brother,” he recalls. “But I was always on time for my entrances.”

The following summer, Tony joined the Robin Hood Theatre, a stock company in Delaware. In all, he was there for five summers. “I had the same job I had in Vermont,” he says. “Except that this time the scenery shop was in a cave where they’d formerly kept wine and apples. It was pretty wet—water kept dripping down he walls. And for company we had spiders and snakes. But I was still fascinated.”

From Delaware, Tony’s conversation is likely to jump to Florida. “I was given a chance to play leading men when I went down to Rollins,” he says. “ ‘Laura,’ ‘Goodbye My Fancy,’ ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’ were some of the shows. And I did winter stock in Winter Park.

“That’s where I goofed again. But, you know, I like it when people don’t come in on cue. Gives you a chance to take command . . . build some lines . . . save the day. Maybe everybody doesn’t feel that way,” he adds modestly.

“Anyway, Kay Francis had come down to do a play. There was a love scene at the end of the first act, and I was supposed to interrupt it. But I got my entrance cues confused and was a little late—more than a little late. Eventually I heard Miss Francis ad-libbing, ‘Roger, where is that boy? What’s he doing out there?’

“It could have been the longest love scene in the history of the theatre,” Mr. Perkins says thoughtfully.

At the end of his freshman year at Rollins, Tony decided that it was time to tackle Hollywood. He was prompted by the news that M-G-M had purchased the play “Years Ago.” Since he’d done it in summer stock, he could practically hear Culver City calling for him. “So I went out with the general idea of getting myself the part.”

He chose to go by way of New Orleans and Arizona and made it in six days. Riding his thumb. “It was a non-stop trip,” he recalls. “I slept in the back seats of the cars. Nothing much happened—unless you count the beer-truck incident. . . .”

The beer truck, with Tony as a passenger, was going up a hill when there came a rather deafening noise. The truck came to a quick stop and Tony and the driver jumped out to check the damage. It was considerable. The back of the truck had flown open and the cargo was gone. “There was a whole river of beer down the hill,” he recalls. “About all we could do was try and get the broken bottles off the road. And, man, was it a hot day!”

When Tony reached Hollywood, he wangled an introduction to George Cukor, who was to direct “Years Ago.” It was then that he discovered that no work was being done on the picture at the time. “But I thought I’d hang around.”

He was almost ready to leave when M-G-M executives decided to test a prospective leading lady and remembered the young man who’d been haunting them so effectively. “I was supposed to be on the sidelines,” says Tony. “But Mr. Cukor sort of made it my test as well as the girl’s. It was a lot of fun to do, though I was sure I’d done very badly.”

With this thought in mind, he returned to Rollins. Months later, a telegram arrived from Culver City. He read it. And reread it. The picture was ready to roll and M-G-M was requesting that he report immediately for wardrobe fittings. A leave of absence was arranged and Tony caught a California-bound plane.

His welcome was a little strained. “My fault,” grins Tony. “I hadn’t heard a word about the picture and my first question was, ‘Who’s in the cast?’

“They looked at me as if I’d just gotten in from the moon. ‘Don’t you know?’

“These days they talk about ‘New York actors. Well, the reaction to me was, ‘Who’s this actor they’ve imported from Florida?’ ”

As Tony puts it, the picture—retitled “The Actress”—didn’t exactly tear down the walls. However, it did give him a start as a professional. He flew back to Florida to finish out his school year. Then, on the theory that television work would come his way when the film was released, he transferred to Columbia University in New York.

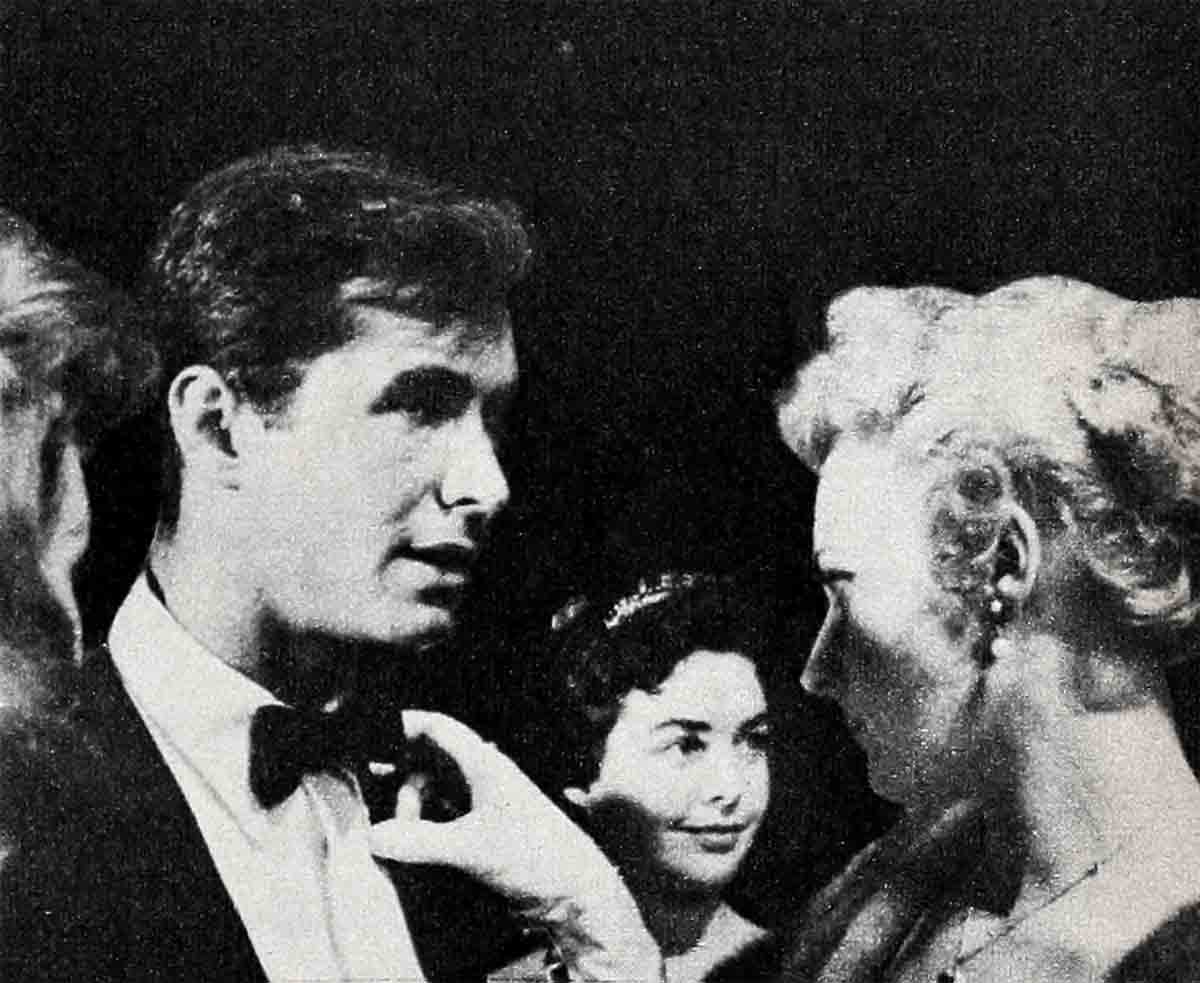

His reasoning was entirely correct. As a result of “The Actress” he found an agent, MCA. He also won good roles in television. And from television, Elia Kazan chose him to follow John Kerr in Broadway’s spectacularly dramatic hit “Tea and Sympathy.”

As it turned out, Tony’s debut day was a test of both actor and scholar. Asked if he would play a matinee with Deborah Kerr, before Joan Fontaine arrived to take over the part, Tony agreed. However, he hadn’t reckoned with examination time at Columbia.

Hopes high, he broached the all-important question. Might he postpone the exam which was scheduled for the same day? “Sorry,” said the professor. “No.”

But the professor knew his Perkins. “I’m sure you’ll manage both,” he added, not unkindly.

Tony did, racing from classroom to dressing room. The results of the exam were quietly filed. But word of his outstanding stage performance was spread the length and width of Broadway.

In July of 1955, director William Wyler made a trip to New York to complete the casting job on “Friendly Persuasion.” He was searching for a youthful actor who could portray a teen-aged Quaker of the Civil War years. Tony arrived for the audition, took a quick look at the script, read for Wyler and his assistant. He walked out with the part.

It was only a matter of time before Perkins’ progress began to set Hollywood on its ear. Actually, he first crept up on the town quietly, as a notice in a trade paper. The item said that he’d been signed for a movie.

Next, he was hearsay. Photographers, who can take stars or leave them, mostly without comment, visited the “Persuasion” set to shoot pictures of Gary Cooper. They returned raving—about Tony Perkins.

Then director Wyler, rarely quoted on newcomers, was quoted and requoted, “I wish all actors were like Tony.”

On the strength of the rushes, he was signed to a long-term contract by Paramount. And the studio, which generally buys properties only for established stars, announced the purchase of “The Jim Piersall Story” and “Joey”—for Tony Perkins. While the scripts were being prepared, Tony created the role of “Joey” on television, and made a record of the song from the show. Then he was given a co-starring role in “The Lonely Man.”

On the latter set, it was obvious that Tony had come a long way—and that he’d acquired a host of rooters. And they were just as enthusiastic as the Theatre Arts professor who had begun to boost Tony back in 1951. “You should interview our leading man, young lady,” he told a fan-magazine writer visiting the Rollins campus. “This boy has what it takes. He’s going to be a star.”

The writer politely explained that it was customary for fan magazines to run stories on motion-picture personalities.

“He’s been to Hollywood,” persisted the professor. “He’s in ‘The Actress.’ ”

Taking old school ties into account, the writer hedged politely.

“All right,” said the professor. “All right. But someday you’ll write a story on Tony Perkins.” His tone implied that she’d also eat her vintage 1951 words.

Well, professor, I know what you mean and this is the story. I’d just like to add that words never tasted so good!

THE END

—BY BEVERLY OTT

BE SURE TO SEE: Tony Perkins in “Friendly Persuasion” and “The Lonely Man.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1956