They Did It The Hard Way—Rory Calhoun & Lita Baron

Ever work for two years for exactly no dollars and no cents? Ever been accused of ingratitude toward a friend? Been broke, in debt and had the credit company come after your automobile? Or still more incredible, have you ever tried to get out of a job paying you upward of $2500 a week?

Any one of these experiences is enough to send the average citizen into an emotional tailspin. For an actor to go through them all is sufficient to send him bleating to the plush offices of a Hollywood psychiatrist to have his emotional wounds bathed and treated.

It happened to Rory Calhoun—all but the psychiatrist.

He is not trying to be a real life hero when he says: “I guess I could go around finding reasons to snarl at the acting business. Granted, it seems a little crazy, but that goes for any profession, whether you’re a sandhog or a sculptor. The breaks come and the breaks go. I’ve had my share of them, both good and lousy, and now I’m on what you might call my third movie career. There have been some mighty bitter years, and some wonderful comic opera experiences.”

Perhaps you have read about Rory’s romantic ranch which is situated near Ojai, California, about seventy miles north of Los Angeles. That ranch has been one of his pet dreams ever since his grandfather used to take him prowling over the ten-acre place years ago. Much later, when the big movie money began to roll in, and Rory had himself a bride, he acquired that property and a lot more—some 150 acres.

“I admit that I didn’t consult my bride about it too carefully,” Rory recalls. “I guess I was afraid to. Lita didn’t look or act too much like the outdoor type. I couldn’t picture her in blue jeans, but I felt I had to get the ranch, as a matter of self preservation. Growing up with the land does something to a man; he never forgets it, and while he may be bored as a boy—as I was with milking cows and feeding pigs—he learns in manhood that being close to the land is mighty important.”

To cut a long story to simple tragedy, Rory managed to buy his ranch. Many were the pictures taken there. He even planted a hay crop which almost paid the running expenses when he was eased out of his contract with David O. Selznick. He had a lot of ground to keep his feet on.

Let Rory tell it: “When the contract was gone things were no picnic. I had an agent who worked hard, but every time he suggested me for a part producers sneered politely. ‘Rory Calhoun? He hasn’t learned to fall off a log yet.’ Meanwhile, I didn’t cave in with remorse. I went up to the ranch and put in some more crops while I hoped an acting job would turn up.

“Then one day a guy with a breezy suit and a stormy manner turned up at the front door to inform us that unless a payment was made the credit company would take away our car. Simultaneously, the telephone rang to inform me that Monogram wanted me for a picture. In those days working for Monogram was like being planted in a cemetery, but I was grateful. Good old Monogram gave me two that year, and I’ve never been so happy about getting jobs. It’s a funny thing; some people can owe a mountain of bills and be nonchalant about it. Not me. It hit me hard to learn that my credit wasn’t good any more.

“Thank heaven for Lita. She went to work a couple of times and grabbed off large hunks of money as she always does. I didn’t ask her to, but I’ve never felt that it’s a sin for a man’s life partner to pitch in and help if she wants to. After all, Lita has been in show business ever since she was four years old. She enjoys it, and I would have been selfish, also a snob and a slob if I had tried to stop her. I knew I didn’t have to stick to acting and could have started pumping gas again. Only now we had the ranch, and I put every spare minute into working the ground so that it would begin to pay for itself.”

It would be nice and cozy to say that with all this hard work between the two of them, Lita and Rory saved the day and paid the mortgage, but ranches and real life don’t seem to work out that way. Rory’s luck changed, and he became an important star at 20th Century-Fox. Recently, that studio shaved a lot of actors off the payroll in switching over to CinemaScope, but they kept Rory on at big money for such pictures as River Of No Return and How To Marry A Millionaire. He was kept so busy that he decided to turn the ranch into a sort of guest hotel.

That should have been great. But all of a sudden there was no water. For two whole years Rory and Lita had been making personal appearances and tucking the money away in a sock in order to buy enough pipe to irrigate the whole place. Net result: two years of hard labor for nothing. There wasn’t as much as a single glass of water to give to a guest, simply because a big oil company and a neighbor above his property had drained it all off. Not intentionally; it was just one of those mix-ups that happen to ranchers.

“I was sore as hell,” Rory confesses, “and I felt like suing somebody. But nobody ever seems to win anything in a courtroom, so we’re talking it over. Meanwhile, the ranch is a big, sprawling, bone dry dream.”

In the beginning actors are humble. Later on, as the bank account fattens, so, frequently, does the head; the star begins to feel that he reached his position strictly by his own efforts and against the deadly opposition of producers and reporters who separately conspired to keep him from becoming famous. In this respect, Rory Calhoun is refreshingly unique.

“The truth is,” he says, “that my career was an outlandish accident, more or less. I didn’t contrive to meet Alan Ladd, way back in 1944. But Alan did happen to meet me on a bridle path when I was down from Santa Cruz to see my great-grandmother. While we were getting acquainted, he wanted to know if I happened to be an actor. ‘No!’ I retorted, rudely, and I guess he was a little miffed by the way I said it. But he just grinned and began talking about my working in movies. I figured I might as well take a fling at it even if it kept me working indoors a lot. Then, it wasn’t long before I had a contract, which was so unimportant you could have squeezed it into the barrel of a water pistol. And even though my scenes with dialogue were cut out of the picture, it brought in eating money. I wasn’t a good actor, and I wasn’t the only one who knew it. The studio soon dropped my option and I found myself fairly broke—far away from the country I loved.”

Now, you’ve heard of actors who used to be bookkeepers or lifeguards or lumberjacks, but you seldom hear of one who has the courage to go back to menial labor once he has had a taste of the soft life.

“When I was out of my contract I could have taken a job as a miner or something, but I liked acting and decided to hang around. When some people say they are busted, it means they have no job and only a few thousand dollars in the bank, plus a few stocks and bonds and a paid-for mansion in Beverly Hills. When I say I was broke I mean that I didn’t own anything except the clothes on my back and I was in hock $300. So I worked during the day at a brickyard, where I stacked and fired bricks. Then at night I slung gas in a service station. A few people I knew in Hollywood thought I’d gone off my rocker. ‘You’re an actor,’ they said. ‘You shouldn’t do menial jobs like that.’ ”

It strikes Rory as funny that people should figure that way. In the first place, just because he had been slapped in the face a couple of times with greasepaint didn’t make him, he figured, a full-fledged actor. Besides, as he puts it, “If a guy’s got two arms, why starve?”

Rory admits that he’s had his low spots. And that they really got him down. Once he poked a guy in the nose when he was feeling lousy and admits that it was a foolish thing to do. But if he makes mistakes, he alone is responsible for them. Criticism of the way he lives doesn’t bother him.

Rory Calhoun says that his becoming an actor, making good and finding the great love of his life was just one big series of lucky situations.

“From the time I left high school I’d been banging around the western part of the United States, picking up jobs wherever I could. There was logging and cow-punching, hauling nets for fish, truck driving and fire fighting. When I got fed up with one of them I’d count my money and run off with it to some new place. I had a bad case of wanderlust. The picture of my life didn’t have any focus at all until my friend, Les Gumm suggested that I try my hand as a forest fire fighter. I didn’t go for that because it paid a lot less than what I got at logging. Les was a friend of my dad’s, too—a California ranger who’d been popping up at our dinner table ever since I could remember. Maybe it didn’t pay as much money, Les pointed out, but the war was on and they needed men badly. It offered more opportunity and if I could swing the financial end of it, I’d learn a lot more that might come in handy to a man. That part got me. I started thinking that if I learned about woodcraft and botany and how to take care of myself in the wilds, I might use the knowledge some day to go exploring. I was just a kid then, and I was a real dreamer, but I wouldn’t have dreamed anything so fantastic as doing my exploring in the wilds of Hollywood. Anyway, with the dreaming and the working, six months later I was a foreman with six men in my crew.

“It was during that time that I came to Los Angeles because my great-grandmother got sick. And then I met Alan Ladd. You should have seen the letter I got from Les after I wrote him that I was going to stay down in Hollywood and try for the movies. He called me six kinds of a dog and then, being the great guy he is, wound up with, ‘If you can’t make the grade you can always come back here.’

“I haven’t taken him up on it yet, but there were times when I was tempted. I forgot about the drawingroom scenes I’d been in and kept on breathing brickdust by day and gas fumes by night, adding up sixteen hours of work every day.

“Then came the break (Alan and Sue gave a dinner for me and invited agent Henry Willson) that got me a contract with David O. Selznick. This one was considerably fatter than the pact I’d had with Fox. I learned more about acting and got better parts, but I never really got very far there. In those days my pal Guy Madison was getting the super star buildup at the studio, and it was Guy who made the big splash. I only got wet around the edges.

“Funny thing, Guy kept telling me that I should be getting the breaks he was and that it just didn’t make sense. In the passing years I’ve often thought that the publice ought to know as much about the guys who don’t land the big fat acting parts as the ones who do. For instance, my big break came when I grabbed off a part in The Red House, starring Eddie Robinson. It meant my whole future. But do you know who tested for the part and did a much better job than I did? Bob Horton. And Bob is just now getting the attention he deserves. The fact of the matter is that I felt so acutely that he should have had the part that I looked him up and apologized for getting it myself. I’m not trying to make myself a swell guy—Bob did a better job; that’s all.” All of which leads us to the spectacle of Rory’s asking 20th Century to release him from his present contract. There are a couple of hundred actors who would give their eye teeth for a regular pay check. But Rory feels that swell as it is to be on a studio contract list there’s an awful lot going on that he’d like to explore—like television and other aspects of show business— but he can’t as long as his plays have to be called by studio bosses. He knows he can see tough times again if he goes it on his own, but there’ll be water on the ranch again soon, so he won’t starve.

He and Lita have their first home now—a two-bedroom place in Beverly Hills. They have lived in assorted apartments, none of them elegant, and one of them consisting of a single room. They kept moving around, but Rory liked to putter and when they finally achieved the house they weren’t in it two days before he began to panel the den.

“The house isn’t anything elegant; it isn’t so big that we’re slaves to it. Lita is busy decorating, and between pictures and on Sundays we drive up to the ranch.

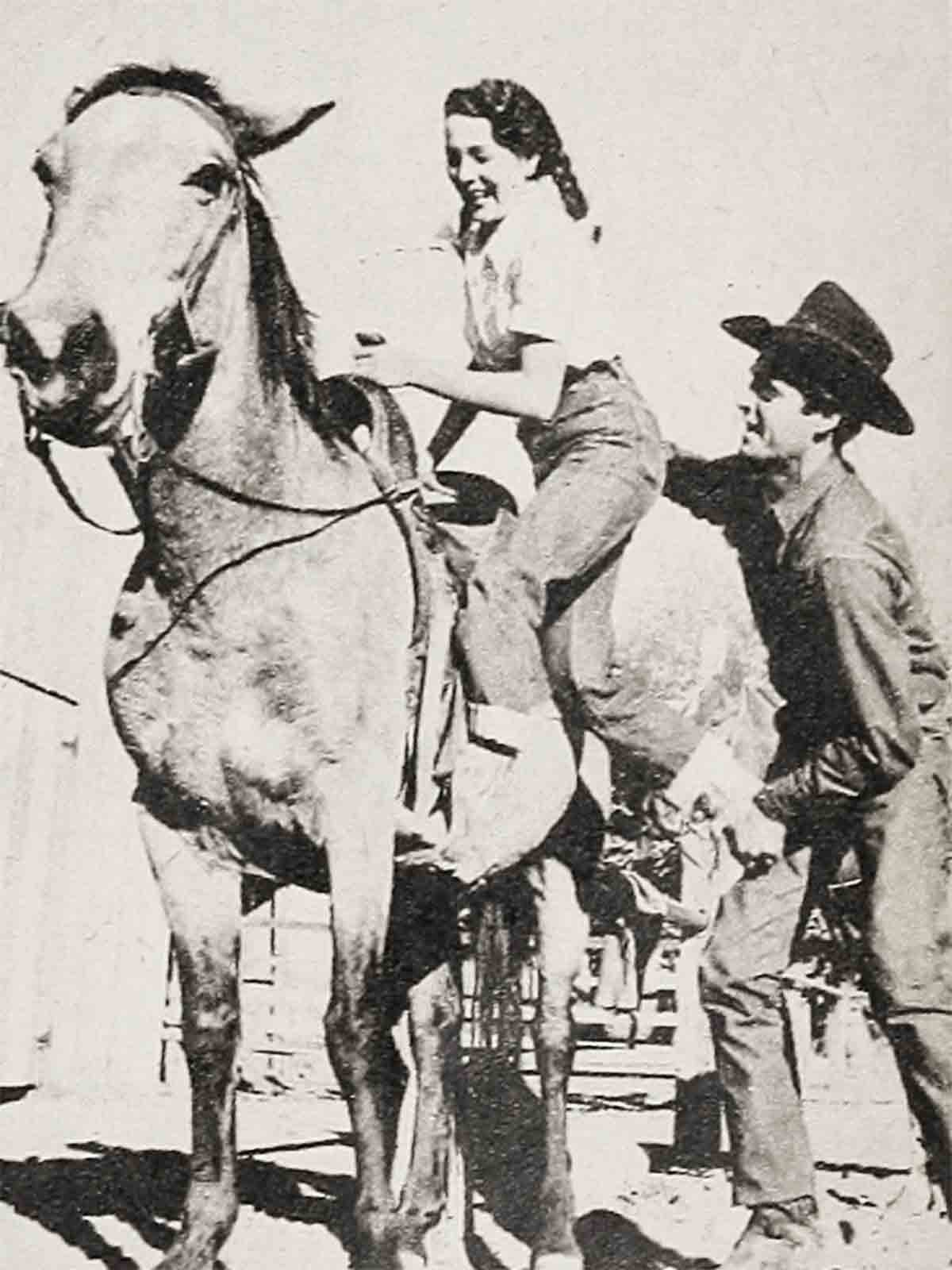

“It took her about a year to get used to the rugged life. I bought her a little horse and a saddle, and now she rides with me. I think she’s pretty well converted. Guy Madison and I took her duck hunting for the first time last fall, and she bagged her full quota. Not only that, but when we got home she announced that from now on she’s going to insist that I go duck hunting at every opportunity. ‘And I’m going with you,’ she said. So I bought a fourteen-foot boat and built a half deck on it. Lita and I have spent many a night aboard it, tucked in sleeping bags up in the duck country.

“The ranch is coming along nicely, too. With water I can plant a crop of alfalfa, and as soon as we can get the feed, we’ll raise calves on spread. There isn’t enough land to graze cattle, but we’ll have sheep. I’ll share crop with the man who lives on the place, and it will be a place to go if times get tough again.

“We’re hoping to have children, and already Lita has decorated our extra bedroom as a nursery. I figure three boys would about do it, and I have daydreams about the time when they’ll be working the ranch and I’ll be an old man, sitting in a boat all day long and fishing.

“Things have been difficult at times, but right now we’re on top of the world. Once I was insulted at being mistaken for an actor; now I’m insulted if people think I’m not an actor. To top off my blessings, Lita looks wonderful in blue jeans.”

THE END

—BY STEVE CRONIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1954