Our Little Ham

Alan Ladd winked at his wife sitting on the sofa beside him and looked poker-faced out through the wide-opened glass doors to the patio. A smile flickered at the corners of Sue’s mouth but she suppressed it and looked directly ahead, too. Outside in the bright sunlight the shrubbery to their right quivered and occasionally they could see a bare foot moving behind it. The family boxer, Brindy, and three brown dachshunds frisked at the bare feet, stopping occasionally to strike head-cocking poses, deeply interested in what went on behind the greenery.

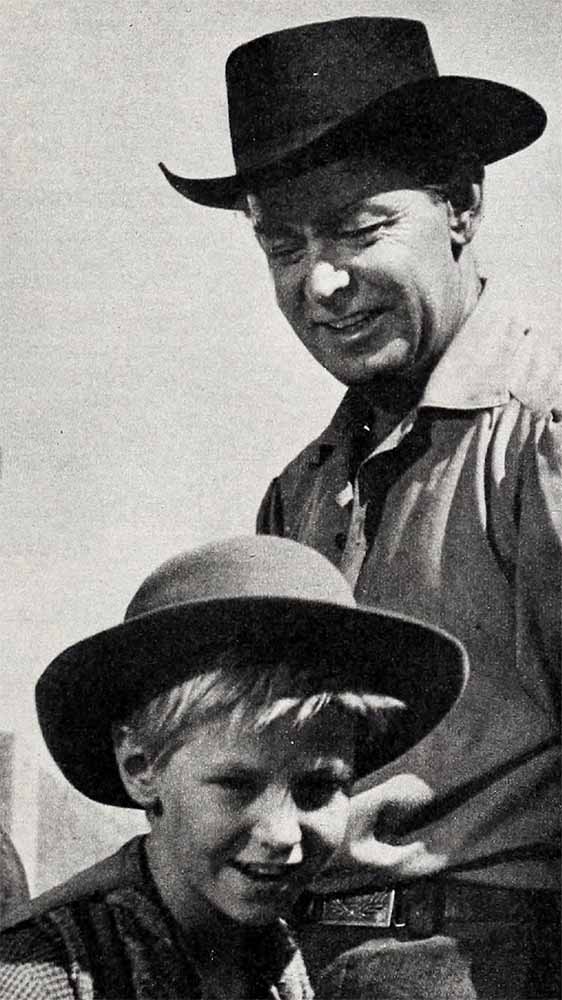

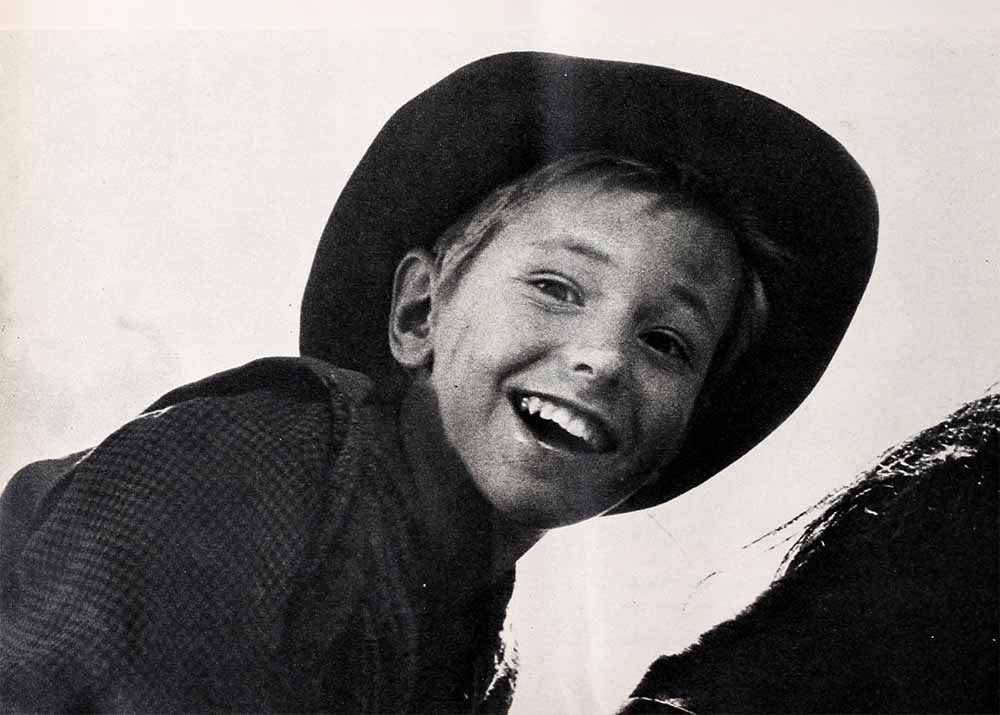

Presently a tow-headed boy, wearing one of his father’s coats which swallowed his arms and legs, stepped from behind the bushes, walked gravely to the middle of the “stage” and bowed. Behind him the family swimming pool shimmered in the sun, backlighting him. “Ladies and gentlemen,” said ten-year-old David Ladd, “we now present David Ladd imitating his father in scenes from ‘Shane.’ ”

The lad’s performance moved Alan more than he would let on. He knew why David had chosen the picture’s fight scene in the country store and his heart swelled with love for the boy. David had been visiting on the set the day the scene was shot and, seeing his father, his hero, fighting, had squealed his gleeful encouragement. “Come on, Daddy; hit him, Daddy,” he had shrieked, climbing over other visitors in his excitement.

“David, come here.” Alan got up and took a fighting stance, left arm out, right fist at his face, chin tucked in. “Like this,” he said, feinting with his left. “Never with your right. And keep your chin in or it’ll get clipped.” He dropped an arm to his son’s shoulder, feeling a terrible responsibility.

Should he encourage the boy? He remembered too well the heartaches he had suffered before making good as an actor. He knew, too, that his own poverty and suffering as a boy—including real hunger—had given him a good sense of values and he did not want easy money to spoil David.

Likewise, he knew what people would say—that David had become an actor because he had a drag as an actor’s son.

That evening Alan and Sue Ladd did a lot of soul searching in deciding whether David should act.

The Ladds satisfied themselves that acting would not harm David. But would it do him any good?

Alan and Sue laughed as they remembered some of David’s agile imaginings and were both proud and amused. There was the time when he locked himself in the kitchen alone and did not come out when called. Not meaning to frighten him, the puzzled parents had heard the sink disposal turned on and off, and they listened. After this had gone on for fifteen or twenty minutes, Alan went to the door and demanded that David open up.

“Shh, Dad,” David said, admitting him. ‘I’m having a funeral.” Then he resumed a kneeling position on a chair in front of the sink. Gravely, one by one, he was dropping his tropical fish which had died, into the disposal—and saying a prayer for each.

Alan and Sue were convinced that acting would not hurt him; would help him. But was David, for all his childish play acting, serious? Alan has his own film company, Jaguar Productions, and there was a bit part for a boy in “The Big Land,” which he was preparing to make. But he was reluctant to make the first move. About that time David ran breathlessly into the house one day with the news that Jack Wrather had asked him and Jack Jr., his playmate, if they would like to take , parts in the filming of “The Lone Ranger” as a lark. “Would you like that, David?” Alan asked. “Do you really want it?”

“Gee, Dad, it would be fun.”

The director confirmed the Ladds’ opinion of “the little ham.” “This boy,” said the director, “will end up as an actor whether you encourage him or not. Acting is virtually an instinct with him.”

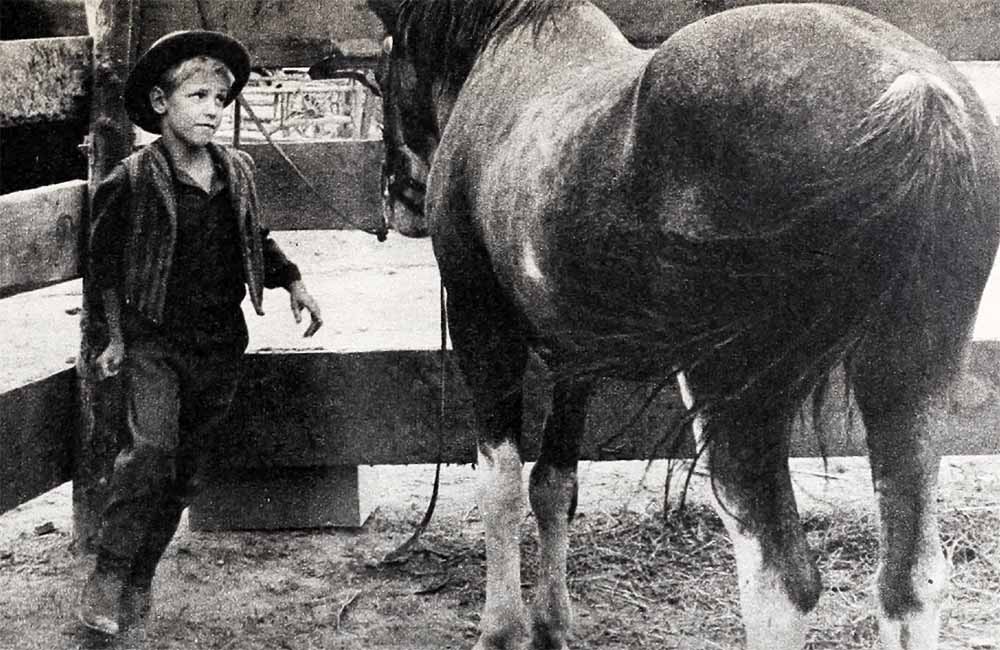

David did well in the part and Alan decided to give him the bit in his own picture. David scored—and proved himself.

Now Alan was embarrassed by David’s fine work in the picture. Wouldn’t people say David had become an actor only because his father had given him the part? “I have two other scripts “but I am reluctant to use David,” he told Sue. “Let’s wait and see if other producers want David—if the boy can make good ‘away from home.’ ”

One day Samuel Goldwyn Jr. sent Alan a script of “The Proud Rebel.” Alan liked it, but turned it down because he was scheduled to make a film for his own company. Goldwyn Jr. then sent a copy of “The Proud Rebel” to Sue, seeking David to play a big emotional role in the dramatic western.

Alan and Sue were both pleased—and alarmed! This was the kind of part which, played properly, could make a star of their boy. Did they want their boy to be a star? Should they give him the chance?

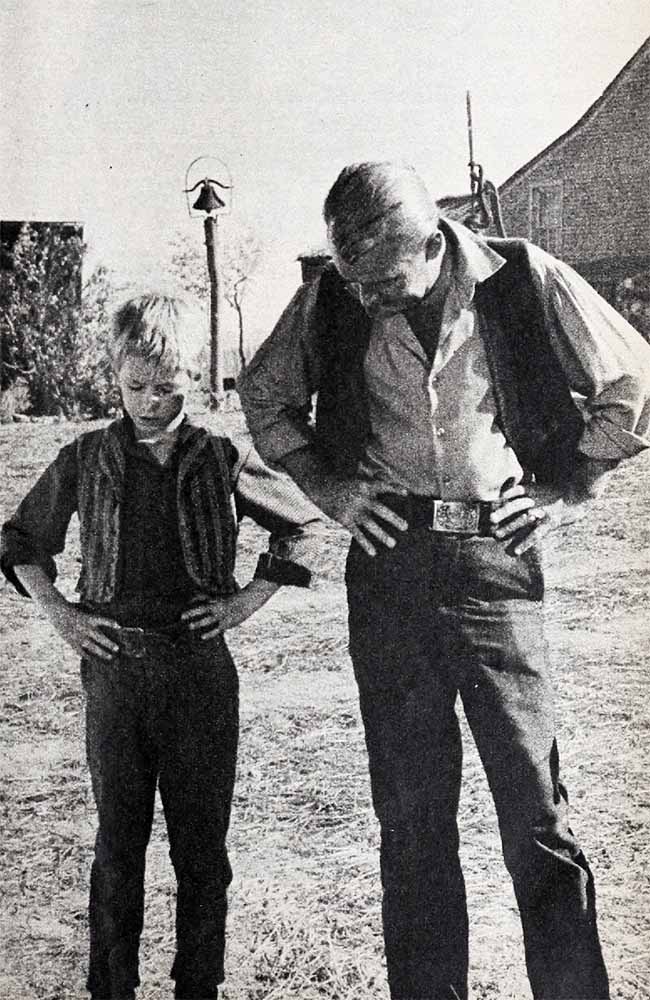

David, accustomed to confiding in, and being a pal to, Alan, asked his father to watch him rehearse. So Alan soon was holding a script of “The Proud Rebel” on his knee, reading the title role of the boy’s father, helping David learn his part. “The more I read the better I liked it,” Alan said. “Then it hit me. Here were father and son roles just right for me and David.”

Meantime, Goldwyn Jr. was trying to establish a rapport with David to gain the boy’s confidence before shooting started. “David didn’t talk much,” the producer recalls. “I’d ask him what he liked—baseball, football, swimming, etc.—but he’d never open up. He gave me only a polite yes or no. Until I asked him about his father! His eyes lit up and he started talking a streak. Plainly Alan was his hero, on and off screen. I sent a script to Alan and got him too!”

When Alan Ladd signed for “The Proud Rebel” he said, “They say an actor doesn’t have a chance against a dog or a kid—but after all, it’s my kid.” Those who heard him knew there was more modest pride than humor in the remark.

With the addition of Olivia de Havilland (after a too long absence away from Hollywood) and Dean Jagger, “The Proud Rebel” began to shape up as one of the year’s biggest pictures. How did David take it? “Actually he didn’t think acting a bit special or glamourous,” Alan laughed. “His earnings didn’t warp his sense of values, either.”

During shooting, David’s allowance went up to fifty cents a week (‘After all, there’s inflation,” said Alan) and his daily wage raised from twenty-five to thirty-five cents whenever he works. David knows he’s not rich. “Let’s see,” he said one day. “Thirty-five cents a day for six days—that’s $2.10 a week—that’s about ten cents after taxes, isn’t it, Dad?”

But the bets are high in Hollywood that after David’s performance is seen this month (he studied sign language—the youngest student at UCLA—in order to portray a boy who has lost his voice from shock), chances are that Alan’s going to have to raise his allowance, when working, to seventy-five cents.

THE END

ALAN WILL ALSO BE SEEN IN M-G-M’S “THE BADLANDERS.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1958