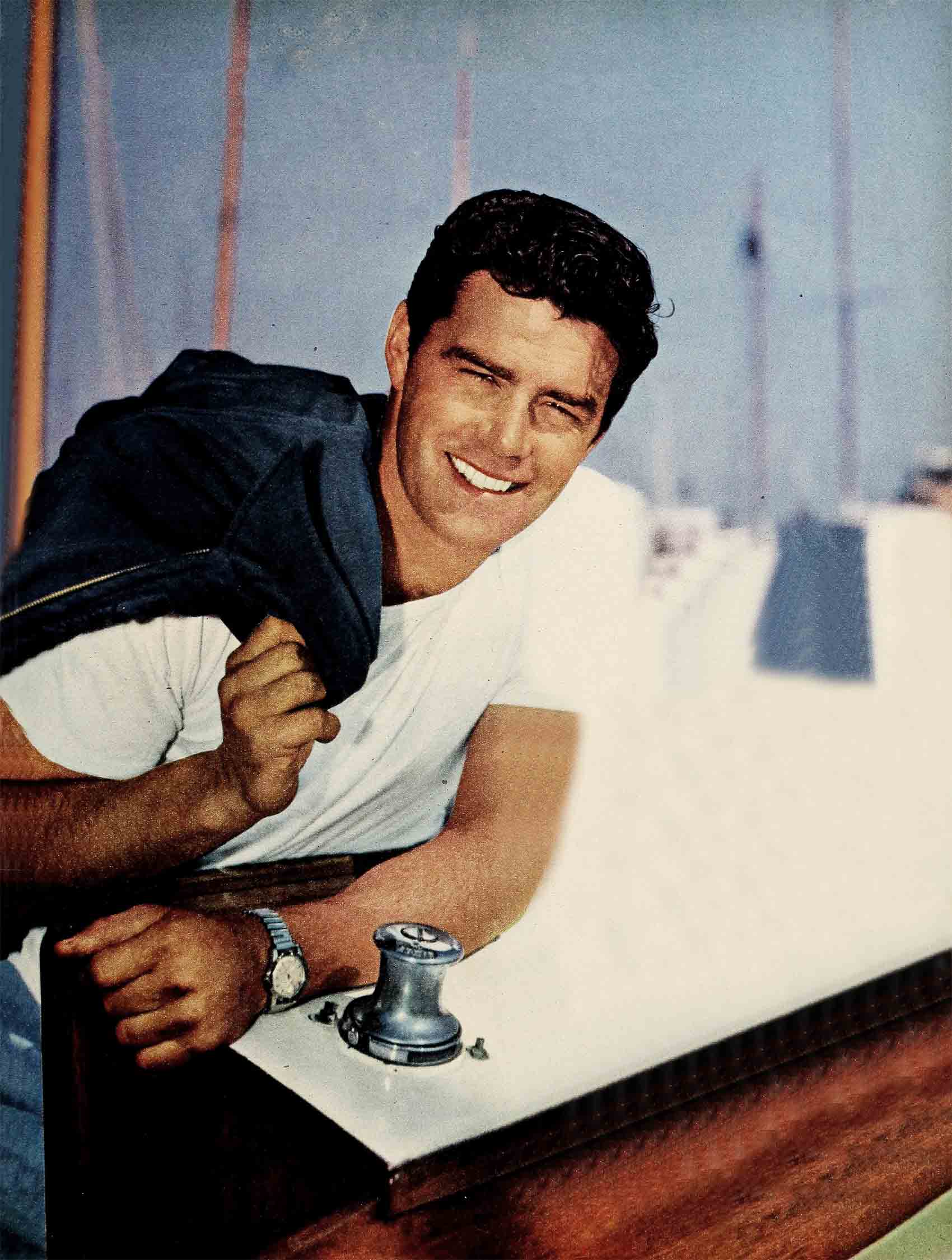

Jeff Richards: He’s the Hunk Of Man Hollywood’s talking about the newest threat to King Gable’s throne!

One murky California midnight a twenty-six-foot sloop nosed out past the jagged rocks of San Pedro’s harbor and into a boiling sea. At the helm a rangy, square-cut sailor gripped the spokes and braced himself for what he was seeking—a scrap with the elements.

Ground swells tossed his slim boat around like a cork and angry whitecaps hissed over the deck. Howling gales whipped his black curls and salt spray peppered his ruddy cheeks like shot. He switched on the running lights, but he really didn’t need them. Nobody else was crazy enough to be out bucking a storm like this.

It was sullen dawn when the lonely skipper steered back to the California Yacht Anchorage, tired and wet as a rain-barrel rat, but happy. As he tied up the boat and shook himself like a pup, Jeff Richards heard a hail from the deck alongside.

“Hey down there! Where the blazes have you been all night?”

“Oh, out for a cruise.”

“Are you nuts?” cried his neighbor. “Don’t you know storm warnings are up?”

“Is that so?” replied Jeff innocently. “Guess I just didn’t see ’em.” Then he went below to sleep.

Luckily for the cardiac conditions of some Hollywood executives fifteen miles away at MGM studios, that typical Richards stunt didn’t travel beyond the rows of pleasure craft bobbing safely up and down at anchor. Luckily, that is, because that solitary, thrill-hunting sailor is pretty precious cargo at MGM right now. In fact, around the lot they’re calling Jeff, “the next Clark Gable.”

Now, that’s a tag pinned hopefully on every new movie hero with muscles and a dark beard for the last twenty years—everywhere around Hollywood except Metro. The King was always king in Leo Land and that was that. But now that Gable doesn’t work there any more, Jeff Richards looks like just the boy to fill the empty footprints he left behind. That is, if Jeff will stay alive and in one piece which, you might have guessed, is always a question.

Besides living dangerously, Jeff looks, acts and even talks like Clark. He’s tall, dark and brutally handsome, with a rocky jaw, beetling brows, a reckless grin and deep brown eyes that send out that old devilish Gable beam. Last New Year’s Day when a bevy of Pasadena Rose Princesses toured the MGM lot, the cuties quivered, “Oh, can we met Mr. Richards?” One cried, “He’s so fascinatingly scary!”

Jeff Richards laughed when they told him that. He doesn’t figure himself a menace to anyone except possibly himself. Like Gable, he’s big, rough, and thrilling to see—six feet, three, and 210, with shoulders like a longshoreman, which he once was, snake hips like a sailor, which he was for three years, and the lithe, graceful get-along of an athlete, which Jeff’s stretches as a pro baseballer confirm. Underneath though, just like Clark, he’s a gentleman not inclined to toss his weight around unless it needs tossing. Then he can handle what occasions arise.

The other night Jeff strolled out of a Hollywood cafe where he’d bandied jokes with the waitress only to run into a roundhouse right to the jaw from her boy friend. In seconds, the boy friend was out cold. Later, he looked up Jeff, saying he wanted to thank him.

“Thank me?” puzzled Jeff, who was expecting something more like a knife in the back. “Why?”

“For not killing me,” explained the boy, with real gratitude, “and for knocking some sense into my head.”

Right now the only people Jeff Richards seems certain to slay are a few million maidens all over the land—with his next picture, The Bar Sinister. It will be his thirteenth movie but that’s not worrying Jeff a bit, nor his bosses either. They’ve had “more Jeff Richards!” yelps from exhibitors for months and sentimental fan mail for Jeff. Those sure signs began back with Big Leaguer, kept ballooning through Code Two, Seven Brides For Seven Brothers, Crest Of The Wave and Many Rivers To Cross until they finally made Jeff a star in The Marauders. In all of these epics, Jeff Richards had hair on his chest but never a girl in his arms. That sad situation will be emphatically corrected with the sock ’em, love ’em and leave ’em job Jeff undertakes next.

All this second coming of Gable talk got going after Jeff was summoned by a desperate Metro director named Herman Hoffman, who was puzzling a mystery almost to the point of collapse. Why, oh why, he pondered, weren’t there any primitive, young, straight-slugging lovers around Hollywood any more? Like—well, the old Clark Gable of A Free Soul, China Seas and Boom Town. Why were all the new heroes so neurotic? Were raw meat Romeos extinct? Hoffman had a star’s part ready to roll and no one to fill it. Then Jeff Richards strolled by like a walking answer.

You’ll see the results when The Bar Sinister hits the screens this fall. But after Herman Hoffman watched Jeff cuff sexy Jarma Lewis around the set like a punching bag, mop up the floor with what was left, then bring her to life with a kiss, he heaved a happy sigh. “Ah-h-h-h-h,” said he, “at last a star who’s not mental—just elemental!”

His studio boss, Dore Schary, calls him “the most virile young star on the lot.” But, as Jeff’s sun rises, so also does a headache. The trouble is, Jeff’s just not geared for Hollywood glamour.

Jeff is a lone wolf, shy, remote and shrinking from the spotlight as it begins to bear down. He dwells all alone on this boat of his, without even a phone.

In five years at MGM Jeff has gotten around to one annual premiére, consented to a publicity date with exactly one starlet, and seen the inside of Mocambo once, six years ago. He declines all Hollywood party invitations politely, doesn’t own a tux and drives an old DeSoto. Half the stars at his studio don’t know him. His buddies are the set workers, one of whom owns a ranch in the remote Cuyama Valley where Jeff goes off for weeks between jobs and lonesomely rides fences by himself. The one big Hollywood star he knows intimately is Humphrey Bogart, on whose yacht, the Santana, Jeff often crews, but they never talk pictures. When Herman Hoffman suggested that Jeff take his Bar Sinister script along one week end and have Bogie give him some knuckle-lover pointers, Jeff was horrified. “I couldn’t do that,” he protested. ‘“He’s my friend!”

Part of Jeff’s reticence can be traced to his own lowly estimate of himself as a Hollywood figure. And part of that stems from the fact that until lately he wasn’t really sure whether he wanted to be a Hollywood figure or a baseball player. Jeff himself explains his rugged isolation by the fact that he’s sweating out an unfortunate divorce that’s keeping him broke. But what really augurs a stubborn tug-of-war is the more basic fact that he’s been a freewheeling maverick almost from the day he was born, and he’s not likely to change.

There were several reasons why Richard Mansfield Brooks, as he was christened thirty years ago in Portland, Oregon, early acquired the independent custom of calling his own shots. He had restless French-Irish-Scotch pioneer blood and the northwest was a wide open land where most people did as they pleased. But the best reason of all was—he had to.

When Jeff was only five, his father, Carl Brooks, dropped his mechanic’s tools one day and just disappeared. That left his mother, Beryl, with no means of support and three children, a situation complicated by the rock-bottom depression.

Jeff remembers clutching his mother’s skirts as she stood wearily in the bread lines of Seattle, where they had moved. He remembers heatless, waterless and lightless stretches in their paint-peeled cottage. He foraged in the woods with Clyde, his big brother, for firewood, and scrounged around markets pinching wilted vegetables for his little sister, Margaret. An aunt contributed clothes and, by taking care of other kids as well as her own, Jeff’s mother made ends touch. Two years later she married an oil plant superintendent named Ernest Taylor and the pressure eased. But Richie never forgot.

While he had a warm house to live in and plenty of food from then on, proud Richie Taylor found a stepfather setup chilly. “I respect my stepdad for the obligations he took on,” as he puts it today, “but maybe he didn’t have much understanding—or maybe I didn’t.” Jeff kept on foraging like a coyote cub throughout his boyhood, going after what he wanted on his own and in his own way. Sometimes it was right and sometimes it was wrong.

Once, raiding a cherry orchard outside of town, the cops grabbed him with loaded gunnysacks and hauled him in to the station. “They scared the pants off me before they let me go,” grins Jeff. “But they never did find out where I lived. I figured that wasn’t my folks’ headache, but my own.”

In more constructive adventures Jeff was just as self-reliant. He cleaned out garages, mowed lawns and peddled magazines, bought old bikes from junk shops and made them work, hammered together his own racing “bugs” for the soap-box derbies. He never asked for a nickel to finance his Saturday kick, playing hockey down at the Civic Ice Arena from five am. until the place closed. That and a dozen other sports built that lean-muscled body. “If there was any game I didn’t play, I don’t know what it could have been,” he says.

He started football scrimmage on vacant lots and played center on his high school team, began basketball arching an old volleyball through a rusty barrel hoop over his shed door and later, while he was in the Navy, coached the game. But the real sports love of Jeff’s life was baseball. It has been ever since the day at six when he happened to bump against the radio and tune in a Seattle Indians game. His mother explained what was going on and since then the crack of wood on horsehide has been like a siren serenade to Jeff.

He was playing semi-pro ball at fifteen, and never doubted for a minute what his future would be—the big leagues.

When he was down in Florida on location three years ago, making Big Leaguer, Pitcher Carl Hubbell, the Yankee immortal, watched Jeff work out on the training camp diamond, and wagged his head in puzzled wonder. “Whew!” he whistled as Jeff scooped them up one minute and slammed them over the fence the next. “What the hell are you doing in movies? You’re not acting—you’re playing big league ball! How come you aren’t in the business?”

“That’s a long story,” answered Jeff, which by then it was. “Just say I missed it.” But he remembered a Brooklyn Dodger offer and a New York Yankee one, too—and he felt a pang that reached way back. Jeff is sentimental about baseball because that and his other athletics were the things he first starred at. Jeff’s sports prowess was the one thing that made him feel important. At studies he was so-so and socially he says he was a pretty sad apple.

There was nothing wrong with him—he liked the girls all right, and they liked him. Rich Taylor’s chiseled features and his powerful physique attracted them, but his native standoffishness and antisocial fix made him a bumbling figure at parties, where he lurked in the corners awkwardly, refusing to dance. He didn’t dance, in fact, until he was in the Navy.

The most distasteful chore Jeff has had in Hollywood was dancing in Seven Brides For Seven Brothers. One circle dance group gave him the hots and colds until he decided just to be natural and caper clumsily around. Luckily, the result was so comic that director Stanley Donen kept it in.

All this distaste for social graces does to Jeff Richards today is keep him out of Hollywood’s clip joints, but back then for a spell it routed his adolescent group instincts to the wrong side of the road. When he was seventeen he teamed up with a bunch of rowdies at Lincoln High who called themselves “The Boozer Boys Club.” The tag was mostly juvenile braggadocio, justified by mild beer-busts now and then. But the BBC was hardly a Sunday School outfit.

The members were all toughies and they all wore cords, riding boots, T-shirts and a looping brass chain with a bottle-opener at one end. They had officers—president, treasurer and even, incongruously, a chaplain! Jeff was secretary. They hammered a clubhouse in his back yard out of an old garage, fixed it up to sleep eight, and proceeded to raise the roof generally.

Jeff’s interest in the Boozer Boys dwindled when war struck and he had a chance to earn some real money longshoring on the Tacoma cocks packing flour, sugar sacks and lumber into holds day and night on week ends. Sometimes he’d earn $25 on a Saturday.

But what snapped him out of this harum-scarum phase for keeps was a real club with very different ideas to impart—the U.S. Navy. Richard M. Taylor got his greetings in May, 1943. It was his senior year and he received his diploma in advance and left for Camp Farragut, Idaho. By that time his club was famous all over Tacoma. As he registered, a secretary spotted his brass chain. ‘So you’re a Boozer Boy,” she said. “I think your next few years in the service promise to be very interesting!” They were. But really interesting. For a guy who was fighting insecurity, that made all the difference.

It didn’t happen in one easy lesson, of course. There were a few things a black sheep like Boot Taylor had to learn. The hardest was discipline. On his looks they made Jeff platoon leader. But he lost that because he was too easy on the men and grumbled at petty officers’ orders.

Luckily, Jeff had something the Navy could use. As a kid he had tinkered with radio sets, and at Lincoln High he’d specialized in radio classes. When he took an Eddy Test, his score was tops. They shot him to Chicago and pre-radio school, on Randolph Street, only two blocks from the Loop. It was there that Jeff had his first contact with show business. Mayor Kelly’s town kept a big hello and welcome mat out for G.l.s everywhere. Jeff took in the nightclubs and girlie-girlie shows, although at the USO dances he still played wallflower. But the idea of being an entertainer himself never entered his butch-cut head. He’d never even been in a class play. The only play Jeff longed to make was short to second to first.

So, it was heaven on cleats for Jeff when, after primary school at Texas A. and M., he landed at Corpus Christi, Texas, for secondary radio-radar training. There were eight air bases scattered all around Ward Island. And those bases were loaded with big league baseball players in khaki—really greats like Johnny Sain, Sam Chapman, Eddie Sylvester. As shortstop on the Ward Island nine, Jeff played a game almost every week. The pros told him, “Say, Bud—you’ve got big league potentials—if you’ll just stick with it.”

Jeff had teamed up with pretty Pat Sunden in his last year at Lincoln High for about the only gentling influence to offset the Boozer Boys. They had been writing, so on his first eighteen-day leave Jeff hitched down to Long Beach where Pat had a defense job. “Well, everything was swell,” he recalls, “except that Pat was already in love with another guy!” Jeff rescued the situation with her roommate, though, and volunteered one day to go up to Los Angeles for some Yugoslavian light fixtures the landlady had ordered.

But when he called by the store, the clerk said, “It’ll take me two hours to dig those things out of the storeroom. Want to wait or come back?” Jeff allowed he’d come back. He ducked into the Hollywood USO, latched on to a movie studio tour and pretty soon found himself inside Paramount watching Betty Hutton knock herself out. Someone else was rubbering at the rugged good looks of Sailor Taylor even more intently—a studio talent executive named Milton Lewis. The Hollywood he-man shortage was getting pretty desperate. about then.

When Lewis inquired if Jeff was interested in pictures he got only an embarrassed snort. When he pressed, “Got a few minutes?” Jeff said he had more time than money. So he was trotted around to the Paramount brass that afternoon. They wanted to make a screen test the next day but there Jeff balked. “I’ve only got three days’ leave left,” he explained, “and I got plans for those.” They made him promise to come back after he got out of uniform and not sign anywhere else. He said, “Oh, sure, sure.”

“But frankly,” Jeff remembers, “I thought those people were all as crazy as coots!”

So he pushed the insanity out of his mind, delivered the light fixtures, kissed the girls goodbye and hitched back up to the base—and baseball. Because wherever he went Jeff kept his slinging arm limber. The only post-war future that glittered for him was on a dusty diamond. At Astoria, Oregon, where V-J day ended his training, and at Tillamook where he stored planes, Jeff kept in training on service nines. And when they were still processing him out in Portland, he hiked in his Navy blues to the Portland Beaver field and begged Sid Cohen, a relief pitcher, for a workout. He was so sharp that every pitch Sid delivered Jeff sent over the fence. He did the same thing next day and the manager wasted no time signing Taylor on as a rookie, farming him out to the Salem Senators as a shortstop. “I walked out of one uniform right into another,” marvels Jeff. But as most movie sagas prove, Lady Luck takes some very strange shapes. Jeff’s was a trick cartilage in his knee that he had torn coaching basketball at Tillamook. He poked out two-for-three in his first game with Yakima, but he gimped around the bases. Frisco Edwards, the manager, broke his heart. “It’s a shame to drop you, Taylor. Build up that sore knee and come back next year.” But by next year Jeff was in Hollywood—although for a long time he wondered why.

It wasn’t any burning urge to express himself that sent Jeff back down south but something much more elemental, like a growling gut. Out of baseball for a year and his dreams clobbered, Jeff had no racket to fall back on except mending radios, but he’s not the type to hunch happily over a workbench. That’s when he thought of this crazy studio offer. “I figured I had nothing to lose,” he says, “and a job was a job.” He had money enough for a bus to San Francisco and thumbed from there. Paramount took him.

For the next six months, besides drama lessons when he got around to them, about all Jeff did was play ball with the Paramount Cubs. He had so much time on his hands that at twenty-two he enrolled at USC on his G.I. Bill of Rights, showing up at the studio once a week to collect his $150 pay check. A studio strike slowed things down and they dropped him.

That might have been the end of Jeff’s Hollywood saga, because he’ll confess stars didn’t dance in his bright brown eyes—not then. “When you have things plop right into your lap,” he reflects, “you don’t appreciate them at all.” A contract at Warners plopped right after Paramount let him go and just as easily. He even drew more dough—$250 a week. But it was the same story: nothing to do there—six months and out. Even after that Jeff picked up $100 a day every now and then playing lifeguards, football players and flyers. The check was all that interested him.

Jeff Richards was happier at USC than around any studio. He pledged Sigma Chi, moved into the house, played interfraternity ball (his pro record kept him off all varsities) thumped a bull fiddle in a swing combo, studied business administration. He liked it all so much that he’d occasionally tell his brothers, “I’m going to quit this picture stuff altogether.”

It took a girl again and a job to change his mind. And paradoxically because he didn’t get either one.

The girl was a beautiful blonde Delta Gamma named Eleanor Pastori. Jeff tumbled like a load of coal on his first blind date, made it a steady twosome and in his third college year got engaged. About the same time a big Los Angeles dairy company picked him out of 200 applicants for executive training—with enough starting salary to support a wife. But it fell through at the last minute and with it Jeff’s marriage plans. He was so discouraged he broke off with Eleanor, who soon got married and left him holding a large, illuminating torch. What the light revealed to him was, as Jeff says, “that I’d been treating my Hollywood opportunities in very immature fashion.” The business world wasn’t a bit easier or more secure.

In this chastened state, Jeff met exactly the right man. Vic Orsatti is a Hollywood agent who used to play ball with the St. Louis Cardinals, and his brother Ernie starred with the Chicago Cubs for eleven years. A fraternity brother took Jeff out to Vic’s house one night and the pep talk worked. “You can make the grade if you’ll take it seriously,” Vic argued, “but it’s like baseball—you have to train long and hard before you make the team.” Jeff walked out as Orsatti’s client and two days later he was in Louis B. Mayer’s office at MGM. After a test, he signed his third studio contract on the strength of his good looks.

They take the long-range outlook at Culver City, which is just the view Jeff Richards needed. Like a baseball club, MGM operates on the slow and steady buildup for rookies.

Jeff started with a low salary, $125 a week, and a brand new name, Jeff Richards, because with Bob Taylor, Liz Taylor and Don Taylor on Metro’s list, the place already sounded like a garment district. He began grimly repeating, “How now, brown cow,” with diction coach Gertrude Fogeler and making clumsy entrances and exits for drama coach Lillian Burns. Both frankly told him, “You need a lot of work.” Five years later, they agree, “Jeff is ready for big things.”

They broke him in playing a policeman in Tall Target, and the eight lines Jeff spoke weren’t deathless gems. If you saw The Sellout, you might have spotted him as a truck driver, and as a bombardier in Above And Beyond. It was all slow and easy. A lot of times Jeff hid his sex appeal behind black whiskers and rough clothes. He gained confidence with three naturals for a bona fide ball player in Kill The Umpire, Angels In The Outfield, where he played in the outfield and Big Leaguer, which broke him into the Hollywood big league with a respectable third baseman part. Code Two was a frank B-quickie, but Jeff drew a lead out of it with Elaine Stewart and learned so much that the Boulting Brothers picked him to go to England for Crest Of The Wavewith Gene Kelly. Before he got back, MGM had ace writer Dorothy Kingsley penning a special part for Jeff in Seven Brides For Seven Brothers—and that really sent him rolling along at last, although it didn’t exactly build up his ego.

Besides the ignominy of having a singing voice dubbed for him, and all that trouble with dancing, Jeff Richards was pretty miserable batting around with a lot of dancing boys and girls, his head spinning with arty musical jargon and choreography chatter on the set. Luckily, another maverick was around to prop him up. “I don’t think I’d have got through it without Howard Keel,” allows Jeff. “He talked my language and set me straight.”

All this time, nobody has been able to bend Jeff Richards an inch closer to what his buddy, Keel, calls, “Hollywood fol-de-rol.” For a long time Jeff lived with some USC pals in a shack at Venice on the beach, but that was really just a taking-off place for the yacht harbor. Jeff bought his first boat, an eleven-foot sailing dinghy, five years ago. Next, he rebuilt a Lightning Class sloop from the hull up, then traded it in on the twenty-six-foot pic sloop where he sleeps today. Jeff’s wild cruises aren’t as reckless as they seem, because he’s a well-seasoned sailor. He has crewed with Bogart on a lot of rough, blue-water races and with the nationally known racing sailorette, Peggy Slater, too. He still studies navigation at night, chips, paints and varnishes every free day “around the house,” because that’s what his tub has been to Jeff since last November when his marriage broke up.

Jeff met pretty Shirley Sibre down in Cypress Gardens, Florida, a year ago this spring, on a publicity junket that turned into a whirlwind honeymoon. Shirley is a professional water skier from Miami, and for once posing didn’t irk Jeff’s retiring soul. All he had to do for a couple of weeks was skim over the waves with Florida’s shapeliest mermaids perched on his bare shoulders while shutters clicked. He married Shirley four weeks after he first hoisted her up on his shoulders.

He brought his bride back to California, but right away there were a lot of rivers to cross. “What we found out,” Jeff explains it shortly, “is that we just didn’t know each other. There was a blank wall between us.” They tried to get acquainted for five months in a Manhattan apartment, but no charms worked. Shirley flew back to Florida last November and Jeff went back to the boat, this time “purely as a matter of economics.”

With lawyers’ fees, court costs, separate maintenance and eventually a formidable settlement picking his pockets, Jeff frankly states that he’s too financially flat to do much besides what he is doing right now. This April the divorce comes up and he’ll know how things stand. But the unhappy experience hasn’t soured him.

“Sure, I get lonely down here,” he confesses. “A man needs a woman around. Right now I can’t afford to take one out to a decent place. But, I’d give my eye teeth to meet the right girl and get married again.”

Meanwhile, Jeff Richards is comfortable in his loneliness and, after a fashion, happy. When the sun dips past the yardarm he opens a can of beer or has a Scotch straight, strolls ashore for his inevitable rare steak. Then he climbs aboard to puff one of his thirty pipes, delve into his stack of history, geography and nautical books or catch up on the batting averages. Sometimes he scuffs his sneakers up and down the wharf chinning with the other skippers.

But as the Hollywood heat turns on him, Jeff knows he’ll have to give in and change residence sooner or later. “I’d like a little house of my own,” he says, “where I could rig up a hi-fi set and hammer around the place. But I’ll settle for a dressing room at the studio if they’ll let me move in when I’m working.” He’d like a lot of other things, too, he’ll admit—like sports cars to tear around in, guns to hunt with, a ranch someday, a bigger boat and, of course, that wife who will be a real companion in all this.

There doesn’t seem to be any reason why he won’t get them. Because nothing succeeds like success, and with his own progress most doubts Jeff Richards had about acting are slowly evaporating. “Now that I’ve got my foot in the door at last,” he muses, “I like it. It’s a fascinating business. You never know where you are until you’re there, of course, and you’ve got to keep hitting. But you could say the same about baseball, couldn’t you? I want to be a professional performer now—but I’ll never be an actor’s actor. The way I figure, I’ll always be just a personality.”

Those words have a familiar ring. If so, it’s because somebody else said them almost twenty-five years ago—another big, rugged, elemental he-man who went his own way in Hollywood and made the world love him for it. He’s still around, too, and doing all right, although he’ll never see fifty again. It worked for Gable. It can work for Jeff Richards, too.

THE END

—BY KIRTLEY BASKETTE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1955