260.000 Minutes Of Marriage—Marilyn Monroe & Joe DiMaggio

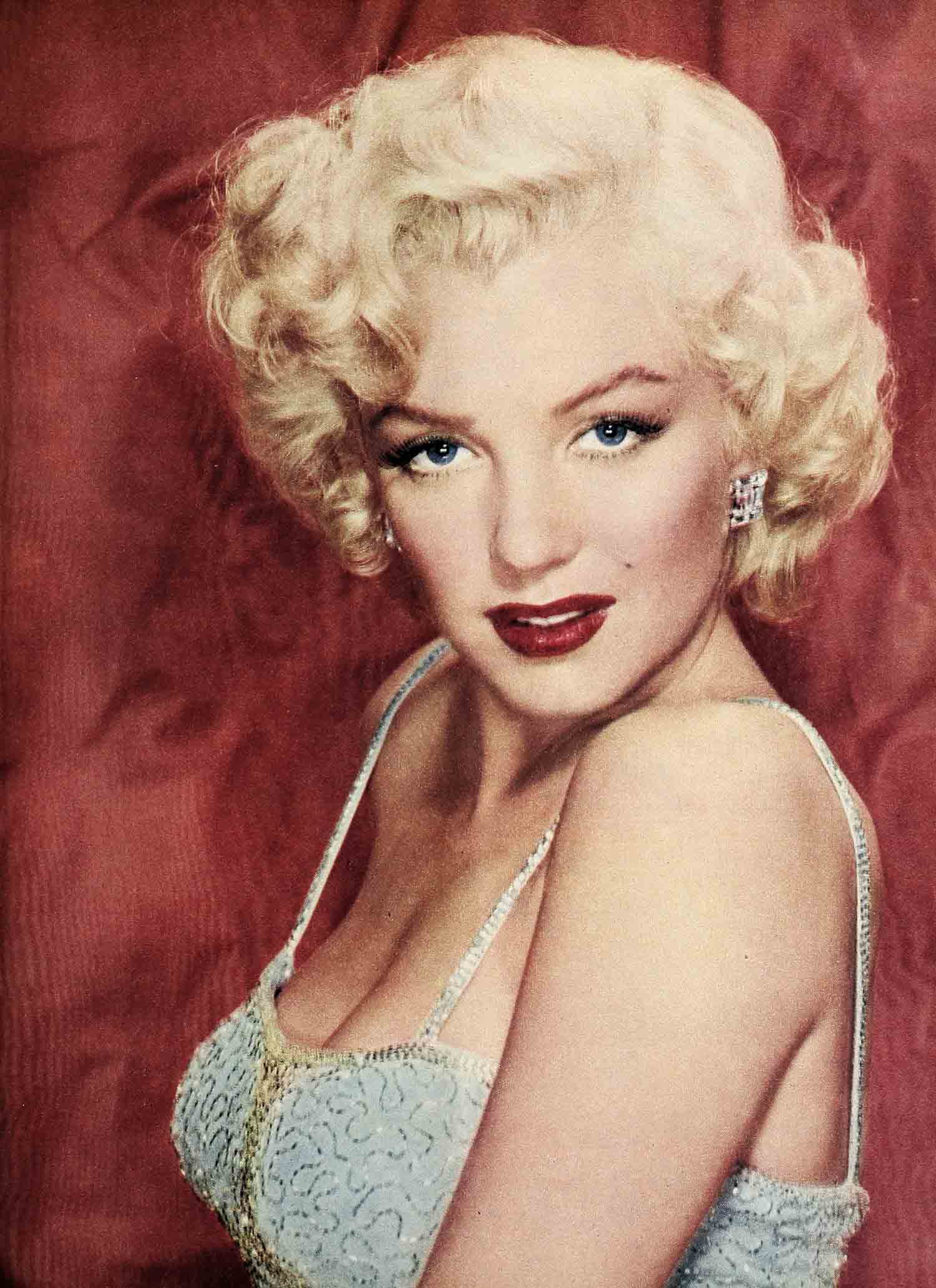

There are two Marilyn Monroes.

When I first mentioned this, it caused much excitement. This is easily understandable to all people who had to be content previously with only one Marilyn Monroe.

However, I was wrong. I should have said that there is a Marilyn Monroe and a Marilyn DiMaggio.

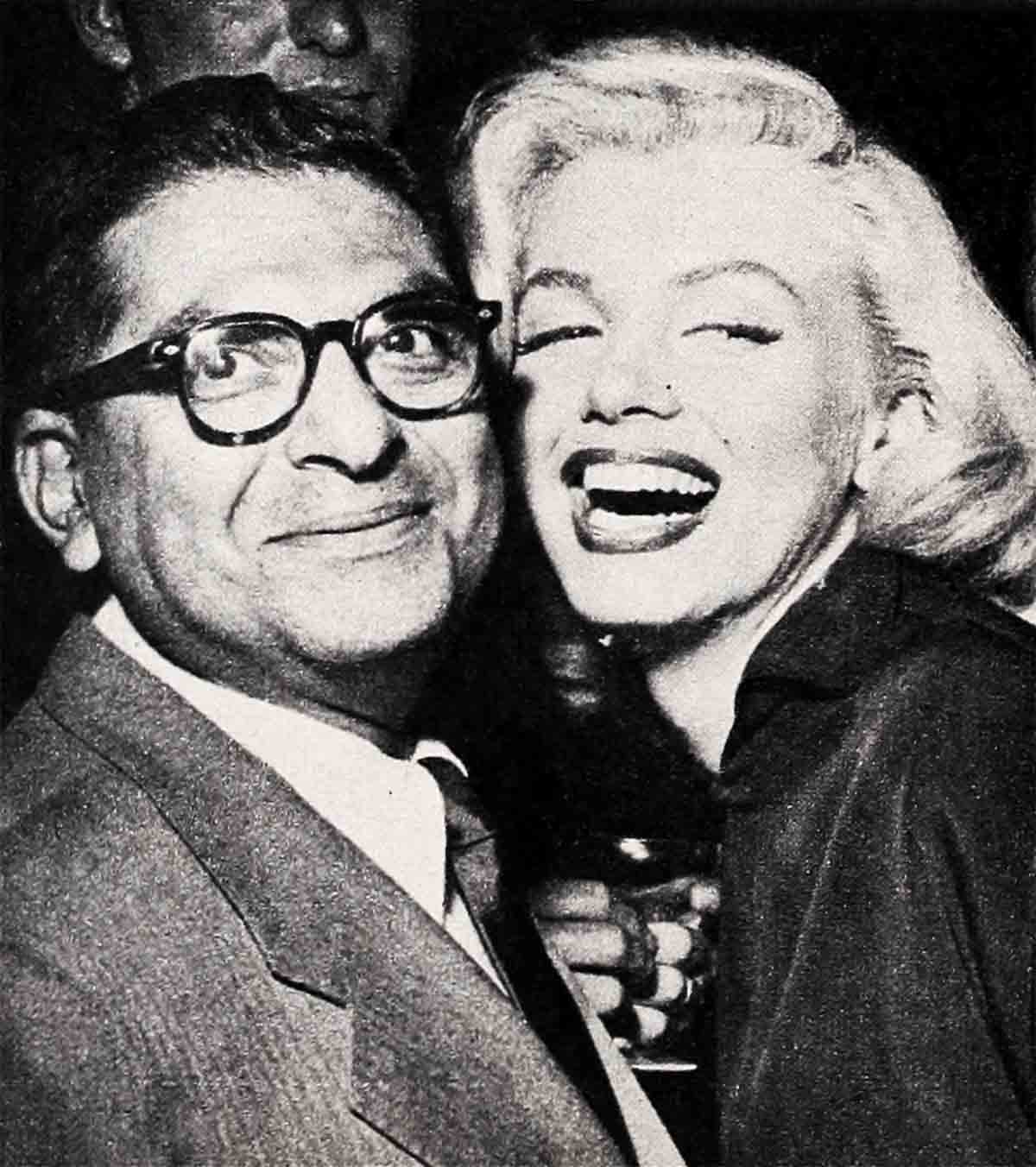

You know about everything there is to know about The Monroe, and I’d like you to become acquainted with Mrs. DiMaggio, who is kind of new. I admit that it’s often difficult to know where Marilyn ends and Mrs. DiMaggio begins, or vice versa. But either way you can’t lose. Come along with me and meet them both in action.

Time: Late afternoon in June.

Place: Bungalow Four—20th Century-Fox Studio.

The small bungalow is partly hidden in the back section of the studio. Marilyn, wearing tight-fitting pedal pushers, a not-too-tight gray sweater buttoned in the front and loafers, is rehearsing her songs for “No Business Like Show Business.” She hasn’t any make-up on except for lipstick, and this is wearing off as she continues to sing.

She sings “Lazy” again… again . . . again . . .

Hal Schaefer, her voice coach, is at the piano. She looks toward him for instruction, guidance and then approval. It takes hours, weeks of preparation for a song which will consume only minutes on the Cinema-Scope screen.

“Madam is improving . . . she opens her mouth and takes a note . . . she’s surer of herself,” said Schaefer, during a breather. “I worked with the best singers. The Madam’s got it.”

I admitted Marilyn was singing better than ever. The piano playing resumed. The singing resumed. More and more of the same. It was almost enough to make me like Liberace.

The telephone, on the desk in the far corner of the room, rang. “I’ll answer it,” said Marilyn, who had sprinted to the end of the room and was already grabbing the phone.

“Hello, Joe,” she said softly. “Gee, I’m glad you called.”

Then and there Marilyn Monroe was Mrs. DiMaggio. The dialogue is placed in evidence. I couldn’t hear Joe, but Mrs. DiMaggio listened bright-eyed. She made these remarks at intervals: “Sure, Joe, if you think it’s best.” . . . “I’m getting along fine.” . . . “I’ve been thinking about you.” . . . “I can get there in time.” . . . “Don’t worry about a thing, Joe, please.” . . . “So long, dear.”

She stepped back and became The Monroe. She told Hal and me she had been talking to Joe on the phone—as if we had to be informed. She explained that Joe had been working hard, moving furniture, trunks, etc., into the Beverly Hills house they had rented. She said she should have been helping him (“It’s a wife’s job”). But Joe didn’t want her to, especially because the picture was about to go to bat. A professional man, Joe understood the importance of going to bat. This in itself indicates how Joe and Marilyn are working

out the career bit between them.

“I’d like to get over to the house before it’s dark. Think we can knock off soon?” Marilyn asked Hal.

“Soon,” he answered. “Maybe sooner. Depends on how you do the next half-hour.”

“If you’d like to see the house,” Marilyn said to me, “stick around.” The piano started. The singing started. Except for breathers, both didn’t stop for half-an-hour.

“That’s all, Madam,” said Schaefer. He added that he was very pleased with Marilyn. “Besides the singing, she stays with it. She’s learned to concentrate on a song. And that concentration can applied to anything. She doesn’t goof off any more.”

“Thanks,” said Marilyn. From the couch she picked up her purse, quickly felt around in it to make certain she had the car keys. Then we were started for the car (a new Cadillac) parked outside near the bungalow. Marilyn didn’t even stop to put on lipstick, which had disappeared during the singing session.

Marilyn drove. And when she drives, she doesn’t have to look where she is going—the other drivers are all watching her. Driving toward the house, Marilyn said we’d be able to pick it out immediately: It resembled a haystack. The DiMaggios had considerable trouble renting a suitable house because they’d take only a six months’ lease; most owners insist on a year’s lease.

“We didn’t want to be tied down for a year,” explained Mrs. DiMaggio. She said they wanted a house in town only while she was working in a picture. After the movie was finished, she and Joe would hurry to San Francisco. Joe owns a house there. A nice, large, roomy, two-story place. She and Joe regard this place as home. Joe’s sister, Marie, and her daughter, Betty, also live there. “Betty’s two years younger than me. We get along fine,” said Mrs. DiMaggio. “Marie is older than Joe. She’s great . . . real great. I couldn’t get along better with my own sister.” Marilyn beamed, proud of her acquired family. A rarity indeed: A wife pleased because she had annexed relatives.

“There’s a house that looks like a haystack,” I said, pointing.

“That’s it,” answered Marilyn. “There’s Joe’s car in the driveway.”

Marilyn parked her car behind Joe’s. We got out. We tried the front door. Locked. Marilyn rang the bell. No answer. “Let’s try the back door,” suggested Marilyn. Locked. She rang the bell. No answer. She shouted Joe’s name. No response. “I don’t get it,” said Marilyn. Neither did I.

Marilyn looked into a side window of the house. A policeman, who had just parked his prowl car in the driveway, suddenly approached. He looked sinister. He wanted to know what we were doing. Somehow, I felt guilty.

“This is Mrs. DiMaggio,” I said, trying to explain. “She was supposed to meet her husband here. They just rented the house and are in the process of moving in.”

“I can’t understand what happened to Joe,” said Marilyn, softly. It would have won over any cop in a movie.

The policeman cased Marilyn, up and down. He gave no sign of recognition. He didn’t ask for an autograph. I didn’t understand it. He looked me over, too—but quicker.

“This house is on the patrol. We’ve got it marked unoccupied. Anyone seen around is suspicious. When you two finally move in, please phone the Beverly Hills Police Department so we’ll know. We keep a close watch on things.”

“That’s nice,” said Marilyn. “Thank you.”

I thought it best not to add to the confusion and inform the cop I wasn’t moving in. We said our goodbyes and he took off to prowl elsewhere.

Marilyn discovered the side window wasn’t securely locked. She lifted the screen and climbed into her new house. Then she opened the front door for me.

“This won’t happen all the time. I’ll have a key,” said Marilyn, smiling. Then: “I wonder what happened to Joe? Well, what do you think of the place?”

I replied that from the little I had seen, it looked compact, comfortable, and was in good taste. I had no doubts it would serve all intended purposes.

“We didn’t want anything big or fancy,” explained Marilyn. “Joe and I like simple things. Wait till you see how I fix it. It’ll be much better. Even a rented house must have some personal things to be really your place!”

I agreed. Marilyn then led me to the sun parlor, directly off the living room. It was an enclosed room and looked out (I guess that’s the expression used) on the backyard and swimming pool. The sun parlor had a long couch, large comfortable chairs, bookshelves and a fireplace where steaks, hamburgers and hot dogs could be barbecued. “I guess we’ll spend most of our time here,” declared Marilyn. “I think I’ll put the television set here.”

She immediately walked around, investigating the room, seeking the best vantage place to put the Tv set.

“I suppose television is important to you and Joe?”

“I watch it, but not as much as Joe. I think I’ll put the tv set to the right of the fireplace. Then Joe or company can sit on the big couch and watch. And I’ll put one of the big chairs here (a little in front of the couch) so Joe can sit there most of the time. I must remember to buy a footstool for in front of the chair.”

She was completely Mrs. DiMaggio. She explained she was going to arrange the furniture so that Joe could watch tv better than anyone else in the room. Joe usually watched the fights, Western movies, movies and a few of the big coast-to-coast shows. “I never say,” continued Marilyn, “‘oh, gee, I want to see such-and-such a program.” She added with a smile, “We’re lucky that we’ve got two Tv sets. If it’s really important, I can turn on the program I want in another room. It happens very seldom, though.”

Marilyn told me that while Joe is watching the fights and dinner is ready, she doesn’t say, “Come to dinner.” She brings the dinner to him. She serves it quietly, quickly on a small folding table set in front of him. “Joe doesn’t have to move a muscle. Treat a husband this way and he’ll enjoy you twice as much,” advises Marilyn.

Mrs. DiMaggio doesn’t restrict this philosophy to only tv and dinner. If any wives and future wives are interested, I’ll try to set down, as accurately as possible, more of the Monroe doctrine.

She believes a man should never have to think about his clothes, except to go to the closet and get them. A wife should see to it that her husband’s shoes are shined, ready for him. “I don’t mean,” said Marilyn, “I have to shine them myself. But send them out . . . see that it’s done.” She continued, “I like to iron Joe’s shirts. He doesn’t want me to. And often I haven’t the time. But I do once in a while. I like to look at Joe in a shirt I ironed, especially the collar. There’s no one who can iron a shirt—especially the collar—like I can.”

I told her she was becoming an accomplished housewife. She said she believed this should accompany marriage. She thought people could mix career and marriage successfully. “When marriage is right, it’s wonderful,” declared Mrs. DiMaggio. “I’d pick it before everything else—because it is your life.”

From this, you and I can surmise that Joe is Number One, that Marilyn places marriage before career, if it should ever be necessary to make such an important decision.

As Marilyn led me into the dining room, she asked, “I wonder what’s with Joe? This isn’t like him. I’m beginning to worry. You’d think he’d phone! Oh, I forgot—the phone isn’t connected yet.”

“He probably thought you’d be late. You know how you are,” I said. “What’s with this room?”

“It’s all right. I want to make it more cheerful, though. A dining room should be cheerful. Not that we’ll always eat here.

Marilyn caught my puzzled look. “I don’t go for a set routine for eating,” she explained. “Having meals in the same place, at regular appointed hours. Phooey! It’s good to change things. We’ll eat here, sometimes; sometimes out by the pool. Often in front of the television set. There’ll be mornings when we’ll have breakfast in bed.”

Marilyn is not just another good-looking, great-shaped blonde; or she never would have become the phenomenal success and tremendous personality that she is. Her experience, plenty of it touched with loneliness, contributed, adding the dimension of depth to character, a quality most of the recruits in the Hollywood army of blondes don’t possess.

“I thought a lot about marriage—and getting married—before I did it,” admitted Marilyn. “I told myself this time I’ve got to stay married. Joe helped me decide. I wonder where he is? Don’t you think he should be here by now?”

“How did Joe help you decide?”

“It wasn’t anything he said . . . No speech . . . It was being with him, knowing someone honestly cared what happened to me. I wonder if you know how important this is.”

I realized Marilyn didn’t expect an answer. I let her talk on. She told me that she felt she had matured enough not only to get married, but also to raise children properly.

“I read where you said you wanted six children.”

Marilyn laughed. “I never said that. It could be, but I never said it. I want to have a child as soon as possible. I should have two. So one doesn’t get lonely, so they can grow up together.”

“It makes sense to me.”

“I’m going to do other sensible things,” said Marilyn. “I’m going to put myself on a budget. Run this house right. So much for food, for laundry, for a maid. How to get all these things done on a budget is stimulating.”

I admired Mrs. DiMaggio’s intentions. Then I asked to see the upstairs part of the house. “Certainly,” she said, adding she must remember to buy candles and order flowers.

“I know it sounds cornball,” said Marilyn, “but I like to dine by candlelight, even if it’s on a bridge table. People shouldn’t be ashamed of being romantic because they’re married. People should always remember how they felt while courting.”

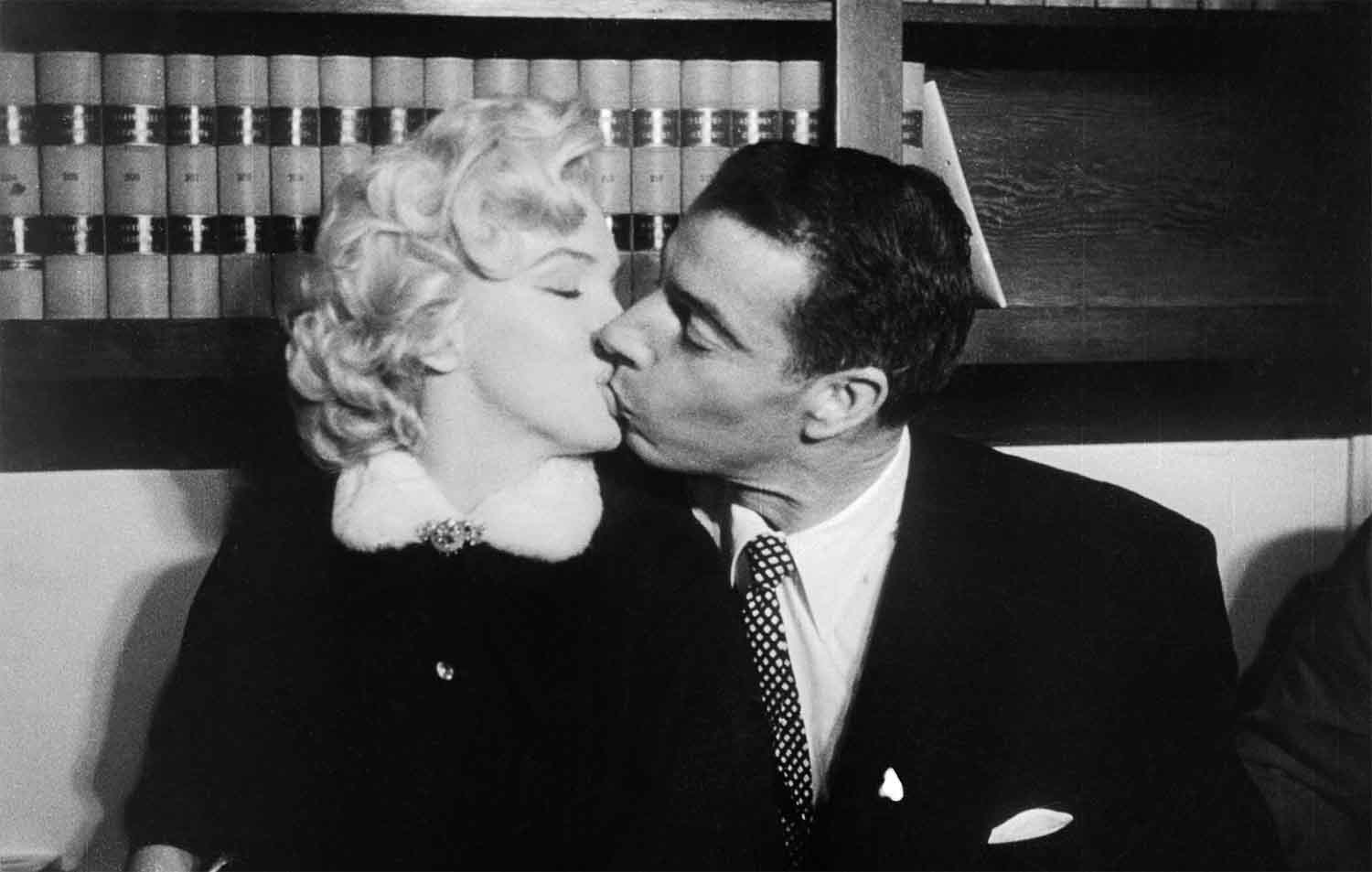

The front door opened and closed. Joe DiMaggio entered calling, “Hey, Marilyn! Marilyn!”

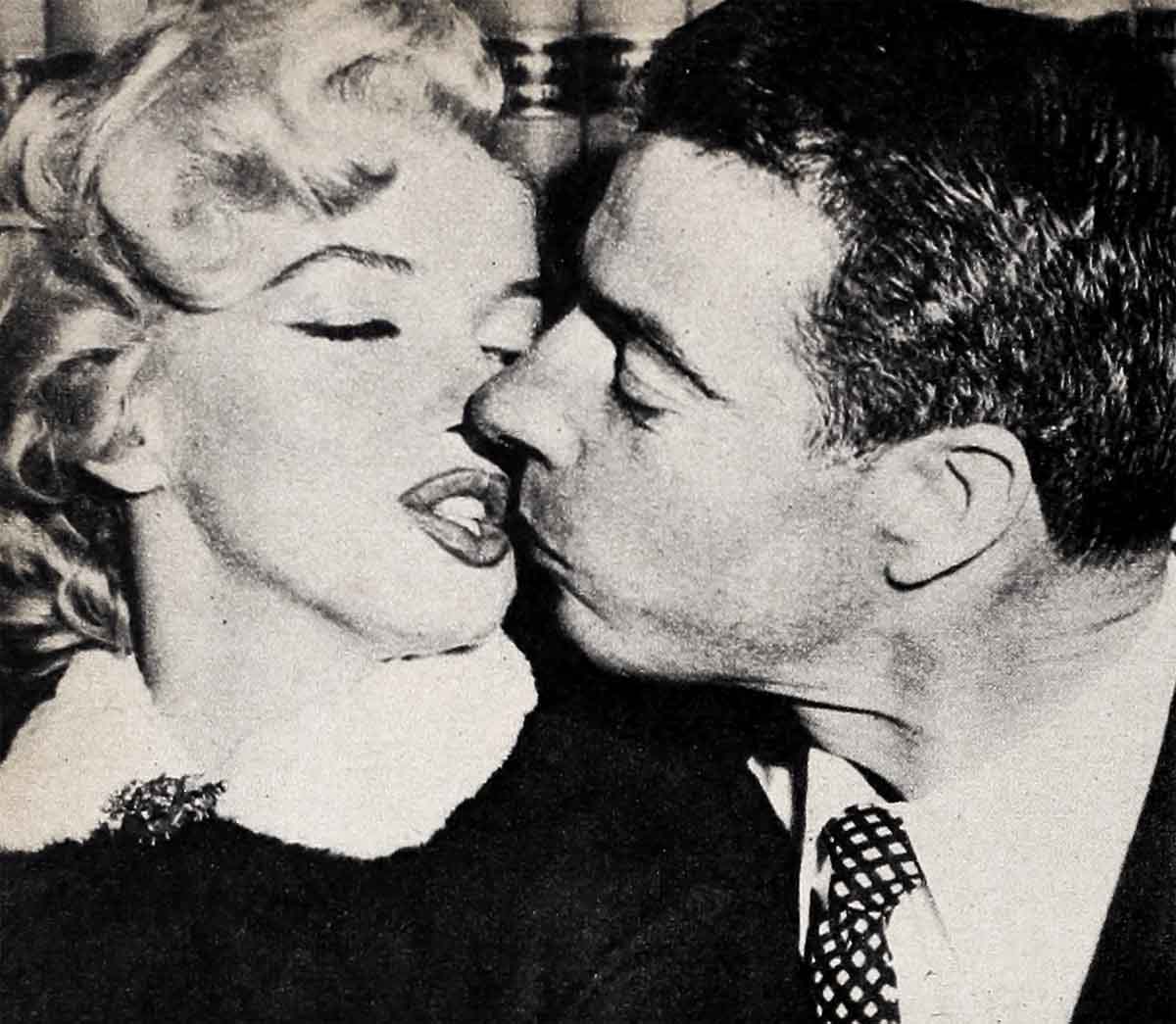

Marilyn called back, signalling where she was. Joe walked fast toward her. They kissed quickly. Joe explained his absence; he had been to the storage company and picked up some of their personal belongings. Vic Massi, Joe’s pal, went with him, and they had used Vic’s car. Vic stood silently behind Joe, and kept smiling.

Marilyn told Joe she was about to show me the upstairs part of the house. Joe said to go ahead. He and Vic intended to bring in the furniture they had taken out of storage.

Climbing the stairs, I asked Marilyn about her wedding presents. “The fans sent me many gifts,” she said. “They gave me vases, linens, silverware, things like that. They were swell. The soldiers in Korea gave me five nightgowns for a wedding present. They made me put on a black lace one while I was on stage—over the dress I was wearing, of course.”

We were standing in a room overlooking the yard and the pool. “I got lots of letters of congratulations,” continued Marilyn. “Most of them said ‘My heart’s broken but I hope you’re happy!’ ”

The gifts and the letters from fans are proof that Marilyn Monroe becoming Marilyn DiMaggio hasn’t affected her popularity. “Did you get any presents from any stars?” I asked.

“I didn’t get a present from anybody at the studio, or from any player.” Marilyn said this in a way which indicated she hadn’t expected any. She is a girl who all her life has been accustomed to receiving nothing.

Marilyn changed the subject. “This used to be a bedroom, but I’m going to re-do it completely. It’ll be Little Joe’s room, when he stays with us weekends. (Little Joe, about eleven, is Joe DiMaggio’s son from his previous marriage to Dorothy Arnold.) I want to make it cheerful and boy-like. That’s why we got a house with a pool. Mainly for Little Joe.”

Marilyn and Little Joe get along great. She loves being a stepmother. She and Little Joe regard each other as friends.

Marilyn told of an incident when Joe and Little Joe were tossing a football back and forth in a room. “I watched,” said Marilyn, “never realizing two people could have so much fun throwing a football at each other. They insisted I join in. Little Joe told me to get ready to catch a forward pass. I got frightened and screamed, ‘Don’t throw that at me, it’s pointed!’ You should have heard them laugh. The biggest laugh I ever got.”

I told Marilyn that from what she had told me and from what I had observed, marriage was good for her. “On you it looks good,” I said.

We were walking toward another room. “Marriage is something you learn more about while you live it,” said Marilyn. “Joe and I have our quarrels. Just like other married couples. You can’t outlaw human nature, no matter who you are.”

I couldn’t argue with that.

“But there’s a way to handle a disagreement,” continued Mrs. DiMaggio. “Every wife should know her man. When I sense there’s something wrong, I ask, ‘What’s the matter? Sorry if I did something.’ If Joe doesn’t answer, I don’t push it. There are some men who, when they have trouble, become silent. You have to respect that, if that’s your man.”

I couldn’t argue with that either.

“Later, when what was wrong is worn thin, Joe will come to me and say, ‘I’m sorry.’ I’ll look at him and say, ‘What’s there to be sorry about?’ You’d be surprised how nice it can be, if done this way.”

We were now in the bedroom. “Don’t tell me,” I said to Marilyn, “I’ll tell you: you’ve got to make it more cheerful.”

She laughed robustly. “A bedroom should be cheerful. And that bed goes out of here. I might put in my bed . . . maybe buy even a larger bed. A bed should be big enough so both can have their own sleeping independence. You know, some people snore, some people kick . . .”

I reminded Marilyn that most of Hollywood’s married celebrities maintained separate bedrooms.

“I don’t believe in that,” declared Marilyn, firmly. “Often in bed you think of something you want to say . . . or something you’ve forgotten. You’re not going to get out of bed and chase down the hall to another room. I don’t buy it. This separate bedroom deal is not in the American tradition. In the pioneer days, did you ever hear of a man and his wife sleeping in separate covered wagons?”

You answer that one. I can’t. I returned downstairs with Marilyn, and chatted for a time with Joe. I told him I liked the house; that I could visualize the improvements Marilyn contemplated. “As soon as we get settled, you must come for dinner,” said Joe. “There isn’t anything formal with us. Drop in any time and watch the fights with me. Make this your home away from Schwab’s.” Joe laughed.

I thanked Joe and said goodnight. Marilyn walked me toward the door. “You and marriage are okay,” I said, glancing back at Joe. “Do you figure it has helped you?”

“It certainly has in my work. I concentrate better. I work harder, longer, and get more accomplished. You watched me rehearse this afternoon.”

Marriage has helped Marilyn career-wise.

We said goodnight to each other. I was closing the door when Marilyn said, “Oh, yes, marriage makes a woman less neurotic. Well, anyway, it does when I’m the woman.”

I walked for a few blocks thinking about Marilyn and Joe and marriage . . . About looking at the television programs you want, while dinner magically appears . . . About candlelight on bridge tables . . . About something sounding cornball . . . About a covered wagon. It’s enough to make a fellow want to get married—to Marilyn Monroe.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1954