Queen Elizabeth Taylor Of Hollywood

You are the lovely young queen of Never Never Land. The Princess Pan.

As a child, yours was the dreamworld of Let’s Pretend. Of autumn leaves and cobwebs. Of youth and joy. A world where dreams never die and time stands still. Yours was an animal kingdom of loving subjects. A paunchy chipmunk named Nibbles was your saucy captain of the guard. Monarch of them all was King Charles—“A fairy horse with wings on his heels.” Together you flew over the treetops and rode on the back of the wind.

From childhood, yours was an invincible faith. You believed with all your heart God would see hat whatever was right for you would come true.

You have needed that faith. And there were jumps ahead of you then—almost too tough to take.

Today you reign in another magic land of pretend. Millions of subjects pay you homage. The young and the not-so-young. Through the magic of make-believe you bring escape and happiness, beauty and romance to all who share today’s dream world with you.

Beauty like yours was born to be shared. But on February 27, 1932, on a foggy, cold London morning when you are born to handsome art dealer Francis Taylor and the former Sara Sothern, a pretty American actress, you are homely beyond belief. In your mother’s own words: “She was the funniest looking little baby I’ve ever seen. Her hair was long and black. Her ears were covered with a thick black fuzz. Her nose looked like a tip-tilted button. And her tiny face was so tightly closed, it looked as if it would never unfold.”

You are christened Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor—and this is your life. . . .

You are ten days old when your eyes open, eyes almost unbelievably beautiful, which are to inspire a whole magic future for you. At sixteen months you begin to give further hint of the heartbreaker you are to become. But far from thinking of romance, your early ambition is to be an animal trainer, and the hearts you want to win are in the London Zoo.

In 1935 when you’re three years old, you make your first public appearance on stage in a benefit dance recital in Queen’s Hall. The then Duchess of York and Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret Rose are among your audience. You give a command performance—but by your own command.

In your white dress and wings, along with the other little angels and fairies, you follow instructions, and facing the Royal Box, you curtsy to the floor and keep fluttering your wings. When the other little angels go off the stage, you’re still flat on your face fluttering away. When you finally realize you’re alone out there, you give an encore. The group applauds and you have your first curtain call.

The applause will grow—and soon. But at three, the sound of a pony’s whinny is still sweeter music to your ears. And your favorite stage is the flower-filled meadow back of an old fifteenth century lodge. It’s your summer home on your godfather Victor Cazalet’s estate. You love the picturesque little lodge. Your family renovate it and name it Little Swallows. You’re enchanted by the tales old-timers tell about it, and you spend happy adventurous childhood holidays here in this wonderful out-of-door Fairyland.

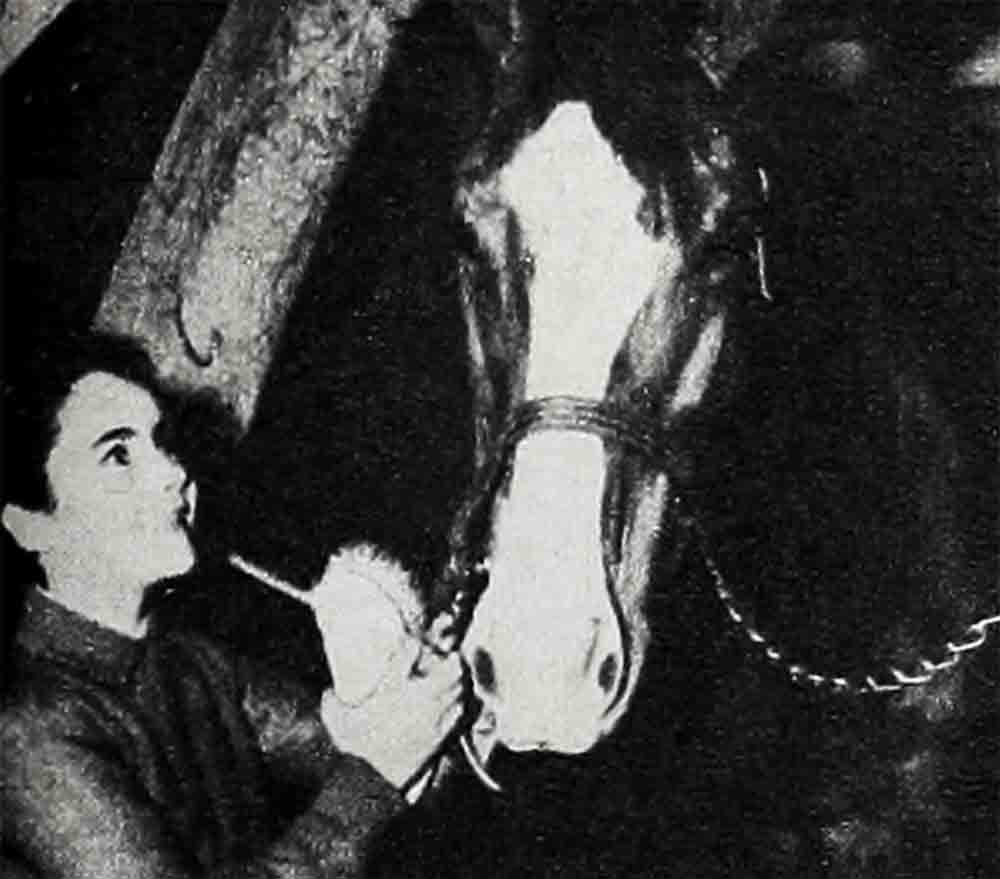

You’re the girl who talks to horses from the age of four. Your godfather gives you a wild field pony and you quickly gentle her. You’re a familiar picture, galloping around the meadow back of the lodge. Remember, Elizabeth?

“I remember the meadow. Funny the way you remember things—when you’re a child. A few years ago Mother and I went back to my godfather’s estate. It survived the war, but it was terribly run down and we couldn’t get into the house. Everything was so much smaller than I’d remembered it. In my mind I remembered the meadow as a huge meadow—wide and long—and the trees so tall. But the trees weren’t tall. It was a tiny meadow. Funny how you remember things. But I guess to a little child it would seem that way.”

To Little Swallows, when you are four, there comes one day a guest of the Cazalets, but you aren’t home. You will meet her a few years from now in faraway America. And columnist Hedda Hopper will help write your name to fame.

In 1939, war clouds are closing in. Your godfather advises you and your mother and brother Howard, ten, be sent to America on the very first boat. In May you sail amid a crowd of chattering refugees. You go to Pasadena, California, to your grandfather’s. You think only of going back to England when the war is over, to your horse and your meadow. You cannot know now that Hollywood will be your Never-Never Land. And you will reign over all the glittering lights that twinkle there.

Even now—at seven—you’re the center of all eyes wherever you happen to be.

By Christmas, 1939, your father joins you in America, bringing with him the paintings of famous artists who’ve sent them to safety here. Among them are the paintings of Augustus John, whose artistic hand will help guide your future, and introduce you to Hedda Hopper, as she well recalls:

“Yes, I paid through the nose—meeting Elizabeth. When I visited the Cazalets’ estate in England, Thelma Cazalet had taken me over to the Taylors’ lodge, but there wasn’t a soul home. Later, when they came to Hollywood, they called me. I thought Elizabeth was an enchanting little girl. Her father was more interested in selling the paintings of various artists than in a career for his daughter, however. I went over to the exhibition, bought two.

“Through the months I kept in touch with the family.

“When Elizabeth was nine years old, she got a contract at Universal-International through J. Cheever Cowdin, whom she also met through the art gallery and the paintings of Augustus John. Cheever Cowdin was chairman of the board of U-I. But nothing happened for Elizabeth at the studio probably because during this time young singers were all the vogue. The studio predicted great things for a little girl named Gloria Jean. Mrs. Taylor said she would like me to hear Elizabeth sing. ‘Bring her over,’ I said. The child stood there singing with a thin, quavery voice. I felt so sorry for her. ‘Oh, no,’ I thought. But when M-G-M began talking about making ‘National Velvet,’ I started hounding them. I thought Elizabeth would be perfect for this picture and I had a column by then. I hounded producers, too, saying, ‘You should see this girl’—after all, I had stock in Elizabeth’s career. She cost me the price of two Augustus John paintings—but I’ve never regretted a penny I paid.”

Yes, an artistic hand guides you through the outer doors of this magic new Never-Never Land. At a dancing school in West Hollywood one of the pupils is Erin Considine, daughter of M-G-M producer John Considine. Her mother Carmen, enthusiastic about your grace and beauty, brings you to the attention of her husband and his studio. They’re very impressed. As for you, you feel instinctively, this is right—that you belong here. Time is to prove this to be true.

You’re dropped by Universal-International when you’re nine years old, but fate still has her charmed finger on you.

It’s 1942 now, Elizabeth. War time. In Beverly Hills one night, two air raid wardens are making their beat. One is your father. The other is M-G-M producer Sam Marx, who’s preparing a picture called “Lassie Come Home.” Making the beat, they talk about you. Stuck suddenly one day for a replacement for the little English girl who’s playing opposite Roddy McDowall, the producer remembers “the little Taylor girl.” It’s Saturday. The studio’s testing twenty-odd girls for the part. The picture’s already rolling. No time can be lost. The studio calls—but you aren’t home. You’re visiting at your grandfather’s truck farm near Pasadena. They send you a wire. Racing against time and traffic to get to the studio before six o’clock, your heart pounds a prayer. Lassie, you love. To play in a picture with this beautiful wonder dog is any little girl’s dream. Your mother calms you with the familiar, “If it’s for you to have it, Elizabeth, you will. . .”

They’ve finished the tests when you arrive. It’s a few minutes to six and the crew’s packing up camera equipment to go home. Producer Marx is pacing back and forth, anxiously watching for you. They must decide on the little girl today. When you rush into the sound stage, the decision is made. As producer Sam Marx recalls:

“Elizabeth was just too beautiful to pass up. Her father had talked to me about her. When we had to replace the little girl in ‘Lassie Come Home,’ I remembered Elizabeth. But I was afraid they weren’t going to make it in time. I kept watching for them that day. And when Elizabeth came running into that room, breathless and beautiful, with her hair flying and stars in her eyes—she lit up the room like sunshine and blinded us to everybody else. We put her right into the picture. Aside from her beauty, we knew she’d been under contract to U-I and had gotten some dramatic training on the lot. We felt satisfied she could do it. A few days later, we were confident we had ourselves a beautiful new little girl star.”

You’re ten years old and most of your waking hours are spent within the walls of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio. This will be your home for years to come. You will rise to fame here. You will be educated here. Through the years your schoolmates will be Jane Powell, Debbie Reynolds, Claude Jarman, Butch Jenkins, Dean Stockwell and many more.

You, Elizabeth, are enchanted with your new life. Within these magic walls each day ends too soon. The sound stages, the sets, the stars and players with their “make-believe faces,” as you refer to make-up—the extras in their colorful costumes—this is a real grown-up land of Let’s Pretend. Story books come to life around you. This is your own dream world come true. . . .

But yours are the normal childhood adventures as well. Your best friend, Anne Westmore, daughter of Wally Westmore, the make-up maestro at Paramount Studio, lives across the street from you in Beverly Hills. As Mrs. Westmore remembers only too well. . . .

“Elizabeth and Anne were always playing ‘dress-up.’ One day I was giving a luncheon entertaining some guests of my own when suddenly they appeared and began modeling for us. They’d decided to favor us with a fashion show. Elizabeth had on her mother’s best maroon velvet, spike heels and her hair pinned high on top of her head—and Anne had on a good print formal of mine. They kept parading back and forth, walking very straight. They were young ladies one minute and children the next. They would go out to Dupee’s stable to ride horses and wind up swinging on a rope in a haystack.”

Yes, there’s plenty of action at home, too. According to your childhood confederate, Anne Westmore, yours are varied experiences. . . .

“The big tree in the Taylors’ front yard really got a working over. We used to play Tarzan all the time. I was the biggest, so I always had to be Tarzan and Liz was my mate. We’d swing from limb to limb to limb. On Sundays we’d usually go out to her grandfather’s truck farm with her family and we’d have a great time playing ‘gangster’ or ‘spies’ out in the barn. We used to play ‘flower shop,’ too. We’d pick all the flowers around, set up a booth in our back yard and play we were selling them. We loved to roller skate and we were crazy for green olives. I remember when we were quite young, our friend and neighbor, Carole Jean Phillips, always had a huge jar of green olives in the kitchen. The three of us would raid her cupboard, put on our skates and race down the street, eating a handful of green olives. We haunted the doll shop in Beverly Hills, fascinated by a big ‘grown-up’ doll they had with real hair you could wash. Mrs. Taylor bought us a little one like her.

“We had our own clothes exchange then, too, and Elizabeth loved wearing hand-me-downs. A girl friend in Fresno, California, Janice Cole Young, would give me her things when she outgrew them and I would pass them on down to Elizabeth, who was the smallest of the three. By the time she got them, third-hand, they were rather worn out. One dress I remember had a hole in it when I got it, but she wanted it anyway. And there was a funny little red voile plaid number that Elizabeth really loved. I remember she wore it to the studio for a lunch interview one day, and two times down it was really worn out, but she just loved it. Once she wore a pinafore of mine to a big premiere.”

In 1943 tragedy comes into your child world for the first time. Your godfather Victor Cazalet is killed in an airplane crash off Gibraltar with General Sikorski, Polish Minister. Tearfully, you keep thinking that some day if you return to your old home, Little Swallows, he won’t be there. . . .

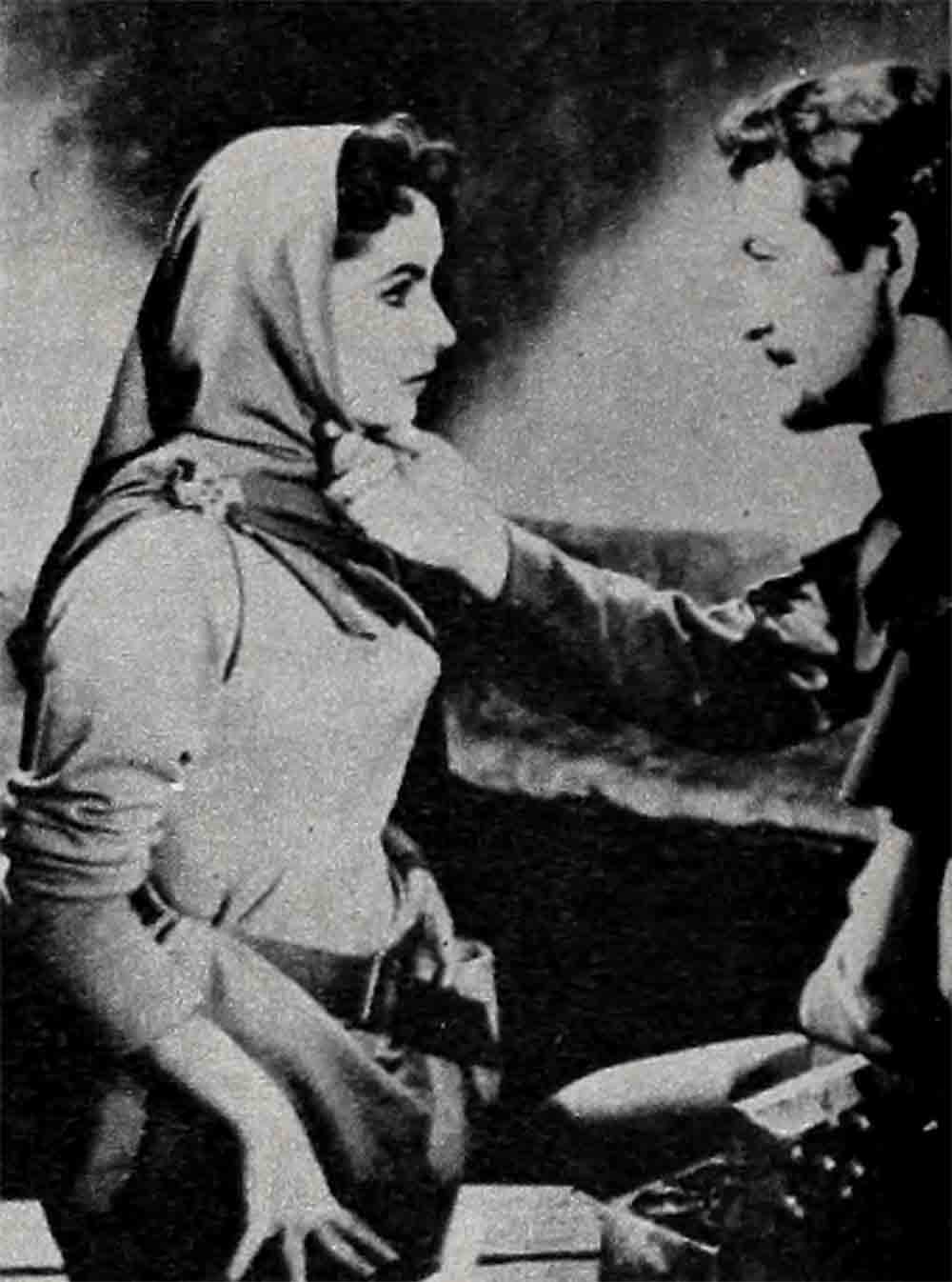

But during 1943-44 your world of make-believe is acclaiming Hollywood your home. You’re cast with Roddy McDowall again in “The White Cliffs of Dover.” Your studio loans you to 20th Century-Fox for “Jane Eyre.” And you capture hearts the world over as Velvet, the girl who falls in love with a horse called The Pi. You ride him to victory in the sweepstakes and to stardom for you.

M-G-M has waited twelve years for the girl to play this part. Until now they’ve never found her. Finally, they decide to make the picture. They test you and you are Velvet, but producer Pandro Berman breaks the heartbreaking news that the picture must roll in three months and the girl must be three inches taller than you! This scene in his office, your mother, Mrs. Sara Taylor, will never forget. . . .

“Elizabeth was sitting over in a corner, her heart in her eyes. I heard her say shyly, ‘Well—I’ll grow.’ Not wanting her to be disappointed, I said quickly, “Why, dear, you couldn’t, you haven’t grown a quarter of an inch in three years. But she loved Velvet who shared her own love for horses and she repeated, ‘I’ll grow.’ All this time Mr. Berman kept looking at her. ‘Honey, if you can grow, I’ll wait for you,’ he said. I had a lot of faith in my child, but this seemed to be pushing it too far. ‘Don’t wait too long, Mr. Berman,’ I broke in hurriedly. But my daughter said confidently, ‘It was never necessary for me to grow before. I can do it, Mummy. I’ll grow for Velvet, she said.”

Looking into those amazing eyes of yours, your mother believes this near miracle can happen. . . .

During these three months, you eat everything they put before you. You drink milk by the gallon. You’re in bed by 6:30 every night. And you personally put the whole thing in God’s hands. You pray if it’s right for you to play Velvet, please, God, make you grow.

During these fateful weeks, riding and jumping horses at the Riviera Club, you fall in love with all your eleven-year-old heart with a magnificent high-spirited gelding whose grandsire was Man o’ War. They say he’s too dangerous for you to ride. Secretly, you steal into the stable and make friends with him. With love and faith, you gentle him. To you, King Charles is a “fairy horse with wings on his heels”; racing over the five-foot jumps with your hair flying like a black carpet behind you, you’re a vision of faith and grace. Now you have another problem for God. If it’s right, you pray for King Charles to play in “National Velvet” with you.

Your faith is rewarded, Elizabeth Taylor. In three months you grow those three inches. And King Charles is cast as The Pi.

In 1944 when “National Velvet” is previewed, you capture critics throughout the land. You yourself can think only of King Charles’ performance, “I knew he could do it,” you say. When a New York critic orchids your performance, but refers to King Charles as a nag, you hate the review and you’re hurt to tears. . . .

On February 27, 1945, another prayer comes true. You’ve prayed if it’s right for you to have him, make it possible for your parents to buy The Pi for your birthday even though he is a “movie star” today. The phone rings; it’s the studio and they’re giving King Charles to you.

You’re thirteen years old now, Elizabeth. You hate doing housework and the dishes. Your screen favorites are Greer Garson and Margaret O’Brien. You paint and sketch and go for Chopin. But you live for Saturdays—when you can go to the stable and ride King. At home yours is still an animal kingdom. And you’re its loyal devoted queen. You have a chipmunk you captured on location, who becomes known to every American family through your book, “Nibbles and Me.” Your dogs all do tricks lovingly for you. There’s a cat named Jeepers Creepers who rides in the basket of your bicycle. And yours is a thoroughly horsey boudoir. A bridle dangles on a lamp bracket. A saddle rides the waste basket. You have a room full of statues of horses that look like a steeplechase stopped in mid-air. And at night in your dreams, you and King Charles ride like the wind. . . .

Christmas, 1945, King gets a new blanket. Nibbles gets a red leash to “go out with” and you, Elizabeth, get a dreamy white fur coat you will wear to the White House.

January 7, 1946, is the biggest day of your life. And the most embarrassing. You’re invited to Washington to help launch the March of Dimes. With excited wide eyes, you watch history books become reality. You visit Mount Vernon and stand in awe in the room in which George Washington died. You stand transfixed in a misting rain with tears in your eyes looking at the Lincoln Memorial.

Now the most important hour of your life is here. Wearing your best black velvet, the new white fur coat and your first pair of long, seamless stockings, you walk on wings into the White House. Excitedly, you visit the Blue Room, the Red Room, the Green Room, dreamy-eyed, remembering those who’ve lived there. The sparkling chandeliers delight you. You feel like Cinderella in Wonderland—that it’s all a dream.

You are Cinderella all right, Elizabeth, but you lose your slipper under Mrs. Harry S. Truman’s chair. You’ve promised your mother you won’t remove your shoe in the White House. But there, facing newsreel cameras and microphones in the Diplomatic Room, out of habit you remove your right shoe when the broadcast’s over. Embarrassed and all giggles, you, Elizabeth, fish around under Mrs. Truman’s chair with your other foot and finally find your shoe. This is a day you’ll never forget.

During 1946 you live in your dream world on the sound stages of M-G-M. Other teenagers read romantic stories but you, Elizabeth, live them, and you are the heroine. Cameramen acclaim you the most beautiful star in Hollywood. You work in a world of adults, but your beauty is far more sophisticated than your years. You’re in the in-between years. Growing up among adults, boys your own age seem too young for you. But at fourteen, you finally are having your first official date. The studio gives you two tickets to a premiere. And you welcome the legitimate opportunity to invite an older boy, Marshall Thompson, to go along. Remember that first date, Elizabeth?

“Very well. We went steady for two weeks. I was invited to the Beverly Hills senior prom and I wanted to go. I thought, this is silly, going steady, and I called it off.”

Marshall Thompson won’t forget this one either. You are in the middle—this first date—of a “triangle.”

“That was rather a mixed-up affair the evening Liz and her mother had tickets to the premiere and they invited me to go. They thought she should go. And the three of us talked it over in a friendly way. There was one hitch. I’d already made a date and I was in something of a spot. Not that I wasn’t flattered by the invitation. Liz was fourteen or fifteen and I was an ancient nineteen, but she was a beautiful little girl. I went with her—and the girl I’d been dating was naturally very upset about the whole thing. You couldn’t blame her. Today, of course, I would behave differently. I had my own two tickets and we took our mothers along and, as I recall, we all wound up at The Pig and Whistle following the premiere.

“Liz looked older than she was. And she had a lot of depth. You could talk to her about practically anything. She was young, but at first I told myself this didn’t matter too much. She would develop from day to day and I was willing to wait. But all the time I knew, before the end of two weeks, it couldn’t go on. Finally I had to face it, she was May and I was September. Liz mentioned going steady. And I said, ‘Well, if you want to—we’ll go steady.’ I don’t know if she caught the casual tone, but I knew it wouldn’t last. When she was invited to the school dance, she decided it wasn’t too good an idea to go steady with the dance coming up. She jilted me for a more important engagement—a senior prom.

Your prom date is Danny Buckley, a friend of your brother and a boy voted the best-looking boy in Beverly High. You wheedle the studio out of the blue chiffon formal you wore to a prom in “Cynthia” and for the first time in your life you’re ready for an appointment on time. This is a big occasion. Remember the prom, Liz?

“I’d hoped for an orchid—and my date brought me one. I was really living. For the first time I went to a beauty salon alone. I wanted to be ultra-glamorous. I came home with fuchsia-colored nail polish on. Mother of pearl. I was so proud of it, but mother held out for a quiet pink shade. Finally, she said, ‘The time has come, Elizabeth. . . .’ and the quiet pink shade it was. She insisted I wash my face three times to give me the clean, scrubbed look. I remember saying, ‘Three times! You just want me to glisten.’ I was sure my dress needed something besides the silver ruffle around the neck. I held out for silver stardust in my hair. I felt it needed something, too, but that didn’t work out either. The orchid really helped. The kids at the prom treated me like Howard Taylor’s sister—just one of them. They talked to me about everything in school. And about all the other kids. Just like I knew all of them, and I pretended I did.”

Yes, this is big night for you. But you have no regrets for your studio school days, have you, Elizabeth?

“No, you grow up faster, growing up around adults. But I’m not sure this is a disadvantage. I was a little disappointed at first when I knew my brother Howard was going to high school and I realized I couldn’t go. You know, the proms, the football games and everything. But I don’t feel sorry for my youth. I enjoyed every minute of it—all except doing a big love scene with Bob Taylor one minute, then being taken back to school the next. I thought, ‘Well, really.’ ”

You’re fifteen years old now, and this is your life . . . your exciting life.

Chintz replaces the saddles in your boudoir. Your animal kingdom is invaded and shared by chattering girls in pedal pushers. Swaggering high-school huskies in T-shirts and jeans. And by a noisy new beige Ford convertible with dual exhaust-pipes and the largest ET initials in all greater Los Angeles—you sleep with the car keys around your thumb. You can’t drive the car yet, but you ease it forward and back on the studio lot and sound its splendor. You are crushed when a city edict outlaws your beloved $39 pipes.

In these teen years you still play a sharp game of catch with Claude Jarman at the studio. You still ride King Charles, thundering along on the sands at Malibu. And yours is still a dream world into which other pedal pushers can’t push.

But now you get dreamy over Dick Haymes’ recording of “Mamselle,” too. You love to go dancing at the Cocoanut Grove and riding the roller coaster at Ocean Park. You go for peasant blouses and bangle bracelets and thickest shoulder pads. You seem cemented to the telephone. And last week’s big crush belongs to the forgotten past. You put the lyrics to a tune. They begin, “Oh the joy and bliss of my first sweet kiss. . . .”

And you’re starry-eyed, when your studio loans you to Warner Brothers for “Life with Father,” to be playing a sophisticated seventeen-year-old.

February 27, 1948, is your sixteenth birthday and they give you a surprise party on the set of “Julia Misbehaves.” At sixteen you play your first grown-up romantic role—Robert Taylor’s wife in “The Conspirator.” And you cry when your little chipmunk Nibbles dies from an over-indulgence of chocolate. You bury him in a box lined with white satin under a rosebush. This is the year, too, you meet football idol Glenn Davis and you’re as thrilled as any teenager when he gives you his gold football.

You go off to London to film “The Conspirators” and Glenn is overseas. You are convinced that this is an important love. As your mother said, “That September in London, Elizabeth wrote Glenn every night and never went out on a date the five months we were there.” Absence and duty and youth dimmed this first crush—and perhaps the charm of a handsome Englishman had something unconsciously to do with it, too.

For that year, too, on an adjoining sound stage in London, you meet the charming British star, Michael Wilding, and you’re as swoony as any sixteen-year-old fan. You cannot know now just how important he will be in your life. Nor that in bewildering hours when your young world seems to collapse around you, Michael Wilding will teach you to laugh again. You had no way of knowing, Elizabeth, but your mother perhaps knew even when she wrote, “I knew that except for Glenn, the man in Elizabeth’s life would be Michael Wilding.”

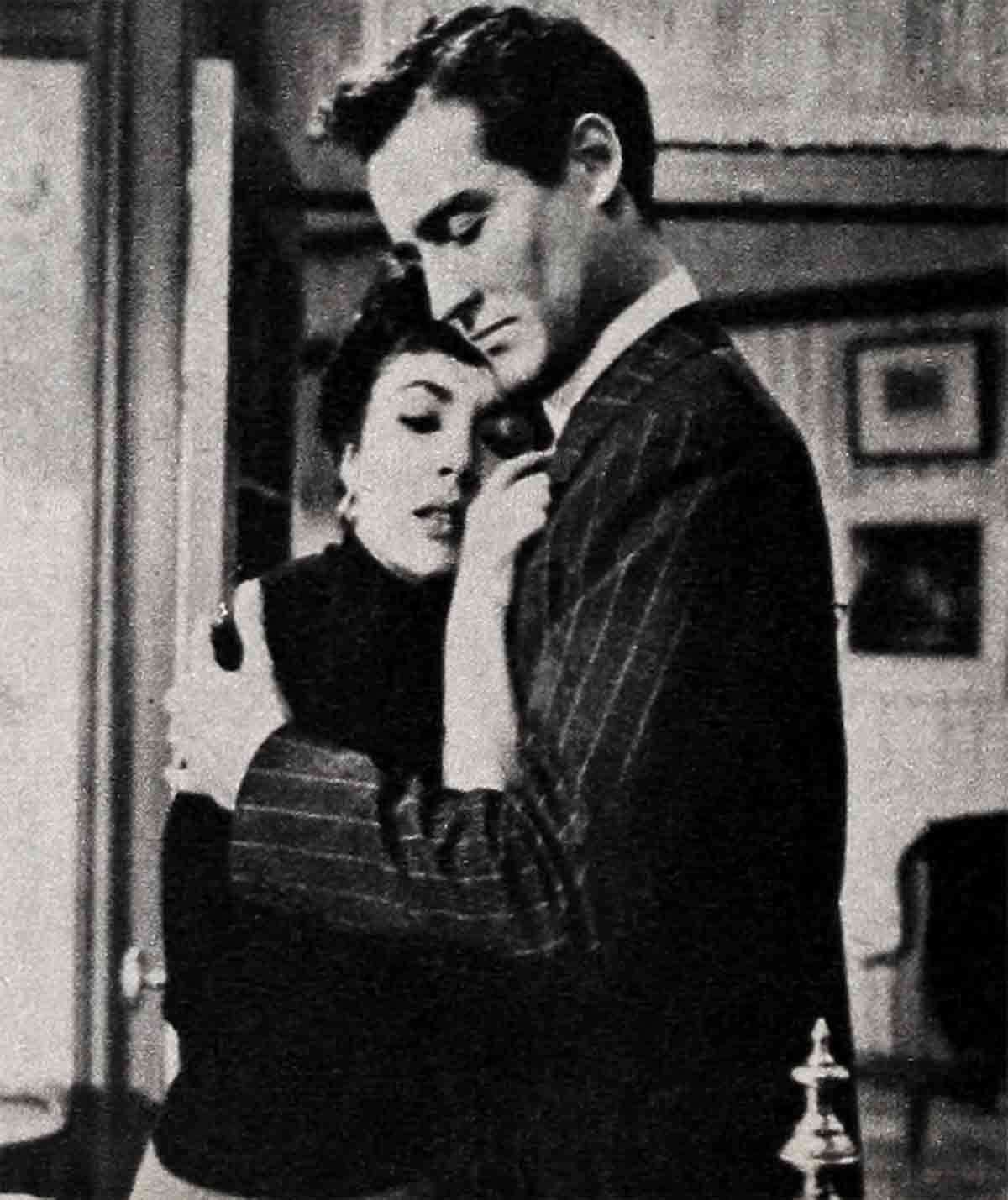

At seventeen your star is still rising on the screen. At Paramount you’re co-starred with Montgomery Clift in “A Place in the Sun.” The director, one of Hollywood’s greatest, George Stevens, predicts your place will be the highest in the Hollywood sky.

“There’s no rung on the screen above Elizabeth and what she can do. She has tremendous depth and a human quality—important with beauty like Elizabeth’s. The audience is with her all the way. I just can’t say too much about Elizabeth. She has the unusual quality of a Garbo—the romantic kind of beauty and drama of Garbo and of all the great ladies of the screen. . . .”

Now you’re successively in love. You’re seventeen years old and trying the wings of youth outside the walls of a motion picture studio. You’re the age when other girls are beginning to collect fraternity pins. But you’re a fabulous beauty. You’ve been engaged to wealthy young William Pawley for a short three months, but break it when he asks you to give up your career and live in Florida. As a famous motion-picture star your every heart beat is a headline. Some of the challenges and cruelties of the outside world close in too swiftly for your young years.

On Sunday, May 6, 1950, in a beautiful ceremony in the Beverly Hills Church of the Good Shepherd, you and Nicky Hilton exchange vows and you radiantly announce, “There is no doubt in my mind that he is the one I want to spend my life with. Since we met, we have never had one quarrel, one moment of misunderstanding.”

But rather than sublime happiness, the following months are filled with heartache and suffering . . . the most difficult months that you, Elizabeth, have had to face in your young full life. And if ever you needed faith and a belief in what is right, you need it now. Your marriage collapses and six months after your story-book wedding, you file suit for divorce from Nicky Hilton, acknowledging more than your share of blame.

“Nick and I had a fairy-tale courtship. Then after the marriage, we weren’t on our good behavior any more and we found out that we didn’t even like each other very well . . . two weeks after the wedding, I knew I had made a mistake. . . . I thought I was mature enough to cope with marriage and I wasn’t. I had always had my own way. Instead of pointing out my faults, people always told me how good I was. I never learned responsibility.”

You’re nineteen years old now, Elizabeth, and you try hard to accept responsibility, to rebuild life out on your own, to discover how you have failed, and you make one statement that proves that maturity often comes through heartache and unhappiness. You say, “I’ve been able to wear a plunging neckline since I was fourteen years old, and ever since then, people have expected me to act as old as I look. My trouble all started because I have a woman’s body and a child’s emotions.”

You return to your parents’ home only to discover you are no longer a child, you are a woman. You hire companion-secretary Peggy Rutledge and move out and into a rented apartment of your own. Peggy Rutledge now recalls your initiation into this new life. . . .

“I met Elizabeth for the first time in her agent’s office. He went out and left us alone to discuss the job and become acquainted. For a little while we both sat there, saying nothing. Finally, I said, ‘Now what do we do?’ Elizabeth said, ‘I don’t know.’ She’d never had a secretary before. ‘I suppose the first thing is to find an apartment,’ she said. And I found a modern apartment. We both lived on Wilshire Boulevard. We had one small problem, Elizabeth’s beloved French poodle, Gee Gee. The manager had made it plain. No dogs allowed. Elizabeth smuggled the dog in, in her coat pocket, and we moved in. But the manager’ was so impressed, having Elizabeth Taylor living there, she allowed Gee Gee to stay. Then the building changed hands. The people who bought it were friends of mine, but they were adamant. No dogs allowed. ‘But you don’t know him. He’s a wonderful little dog,’ I kept pitching. They finally agreed to make an exception for Elizabeth’s dog and we settled down.”

But not for long, Elizabeth. In June you fly to London to co-star again with Robert Taylor, in “Ivanhoe.” Your second day the phone rings. The voice is a familiar voice. Michael Wilding’s. However, you’re the best authority on your courtship.

“Way back when I was seventeen, Mike jokingly kidded me, ‘Some day you should marry me, you know.’ When I met him again in London, the first thing he said was, ‘You see, I told you, you should have waited for me.’ I don’t remember exactly when Michael proposed. But after that first evening when we went out to dinner, my intentions were honorable. He was so friendly and warm. He has such a wonderful sense of humor—a kind sense of humor. He had a lovely sense of understanding and he’s not without charm. . . . He had never seen me on the screen. After we were engaged, Mother and Dad had the studio run ‘National Velvet’ for him. Well, he almost called the whole thing off. I really had to talk fast. ‘But Michael,’ I said, ‘that was eight years ago. . . .’ ”

Yours was not a long courtship. “I want to be married as quickly as possible,” you said, “because happiness is a fragile thing and we have so little time for it.” As for Michael, he felt the same way. “She wants to be married to someone who will love and protect her, and that someone—by some heaven-sent luck turns out to be me. I won’t let her down.”

And seven months later, February 21, 1952, sees the most important wedding scene you’ve ever played. Your own. You’re married in London’s old Caxton Hall. Outside, two thousand fans clamor to see you. You predict the pattern for the years to come when you say, “This is the beginning of a happy end.”

In June, 1952, your happiness is complete. Flying back to Hollywood ahead of your husband to make “The Girl Who Had Everything,” you consult a doctor for the verdict. Barbara Thompson, wife of your first beau Marshall Thompson and today your very good friend, can best describe this happy time.

“Elizabeth went to my doctor and I went with her. I’d just had a baby and she didn’t know a doctor to go to so she chose mine. I was with her when he confirmed the good news. She wobbled out of the office in a happy daze. She’d wanted a baby so badly. When Michael got home they went to Magnin’s and got just what the baby needed—two huge Teddy bears. The Wildings and Marshall and I spent three happy weeks together in Laguna during this period. It was supposed to be a vacation for me, but Elizabeth kept insisting I bring the baby along so that, as she put it so charmingly, ‘I can get used to her.’ ”

With the responsibility of coming parenthood you and Michael buy your first house in Beverly Hills. . . . “We bought it for young Mike,” you say. The house has two bedrooms, a living room and a kitchen. . . . “A huge kitchen. Kitchens are so important,” you feel in your new domesticity. And there’s enough room for an entourage of cats and dogs.

On January 6, 1953, a few minutes before midnight, your son Michael Howard Wilding is born. From the first, he’s a very remarkable fellow, isn’t he, Elizabeth? When he was first born he had so much black hair and he was kind of mangy-looking. But he’s blond and beautiful today. He’s a brilliant child. Funny, how they pick up a jar or something and you say, “Oh, he picked up a jar!” like no baby has ever done it before. You’re twenty-one years old now, Elizabeth Taylor, and you’ve come of age in three great roles—actress, wife and mother. Your career soars on. You star in “Rhapsody” and they’re preparing “The Last Time I Saw Paris” for you. In March, 1953, you replace an ailing Vivien Leigh in Paramount’s “Elephant Walk,” and according to producer Irving Asher: “We signed Elizabeth because of her similar size and coloring—to save our beautiful Ceylon footage and the long shots on Vivien Leigh taken on location there. We were prepared to rewrite several dramatic scenes if she couldn’t play them. Instead, we wrote them more up than down. I wasn’t afraid of anything after I saw her before that camera. She proved she could play anything.”

But your most dramatic scene isn’t in the script, Elizabeth. Two days before the picture winds, a sliver of steel blown by a wind machine penetrates your right eyeball. It becomes badly infected. You undergo two operations—and doctors aren’t sure of saving your sight for you. Your eyes are among the most beautiful in the world. They got you into motion pictures. If anything happens to your eyes, what will happen to you? But what you think about, lying there in the dark with your eyes bandaged—only you, Elizabeth, can know.

“I didn’t think I wouldn’t see again. I was sure it would work out all right. I had enough faith. I believed it would. If it hadn’t, it would have been the end of my career but not my life. I’ve enjoyed the twelve years I’ve been in motion pictures. I’ve loved every minute of them. I wouldn’t trade my life for anybody’s. But my husband and baby, they’re most important in this world to me.”

Yours is a faith still too strong to shake. You believed you would see. And you do. You believed it’s “right” for you to continue to bring beauty and romance into the lives of others through make-believe. But for you, Elizabeth Taylor Wilding, you know the happily-ever-after ending for your own story is not in Never-Never Land but in your home, your son and the husband who loves you. They are your life today.

THE END

—BY RALPH EDWARDS

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1954