Escape To Happiness

PART I

This April, when Doris Day and Martin Melcher celebrate their sixth wedding anniversary, one of their brain children will be very much present to enhance the festivities. This, of course, will be “Julie,” the highly successful suspense drama they made together, with Marty as the producer and Doris as the star. But for all that the film will arrive bearing gifts totaling a million dollars, the happy husband-wife team of Melcher and Day are not planning any immediate sisters or brothers for “Julie.”

“We want more wedding anniversaries,” says Marty with finality. “Not business partnership anniversaries.”

“No more ‘Julies,’ ” pleads Doris.

AUDIO BOOK

And right there you have the key to Doris Day’s happiness, a happiness that had escaped her for a long, long time. Not for a dozen “Julies” offering her a dozen million dollars will she let anything interfere with her marriage. And what makes her stand a little different from most is that she has already turned down the millions. Behind it all is an incredible story, and behind the story is an even more incredible girl.

Doris Day is one of the most written about and least known of all the big stars in Hollywood. As a box-office attraction she is the leading female actress of the decade. In drama alone “Julie” established a record during its first week in New York. When she sings in a picture, the sale of her recordings from the movie will alone make more money than most of the competing films. When she dances in a picture, she breaks all previous records. And when she uses her triple-threat talents to sing, dance, and play the dramatic lead—as she will in “Pajama Game”—movie houses light up their brightest all over the world.

In the face of all this, Doris Day has succeeded in establishing herself with newspaper and magazine writers as the friendly, smiling, healthy, all-American girl from right next door. It makes a fine, satisfactory picture of Doris, and you can recognize her in it; but it has no more detail than a silhouette snipped out of black paper. If Doris weren’t more complicated than that, she’d be the all-American girl from next door, all right, but she’d still be living there.

The explanation favored by many movie moguls bewildered by both Miss Day’s quiet modesty and her shattering impact on the moviegoing public is that there are two Doris Days. They substantiate this remarkable theory by pointing out that Doris is shy and self-conscious in the presence of other movie stars. She’s like a girl just freshly arrived from some place like Cincinnati, Ohio, which, it so happens, is where she comes from. But when this girl gets in front of the cameras a dynamic transition takes place. “Then she’s the star,” says one producer in an awed voice, “and I mean she’s the greatest.”

There may be some merit in this dual personality theory, but it is much too simple. For years Photoplay has been following the progress of Doris Day the star and Doris Day the person. It awarded to the star its coveted Photoplay Gold Medal Award as long ago as 1952. It assigned some of the best Hollywood reporters to uncover the hidden facets of the person. The stories, some thirty of them devoted to her alone, plus countless references, anecdotes, and photographs in features and columns, provide the most accurate picture of her life to be found anywhere. Recently the editors decided to add them all up to produce a full-length portrait. They enlisted the cooperation of Miss Day in sitting for the additional touches that would be necessary to round out a few details.

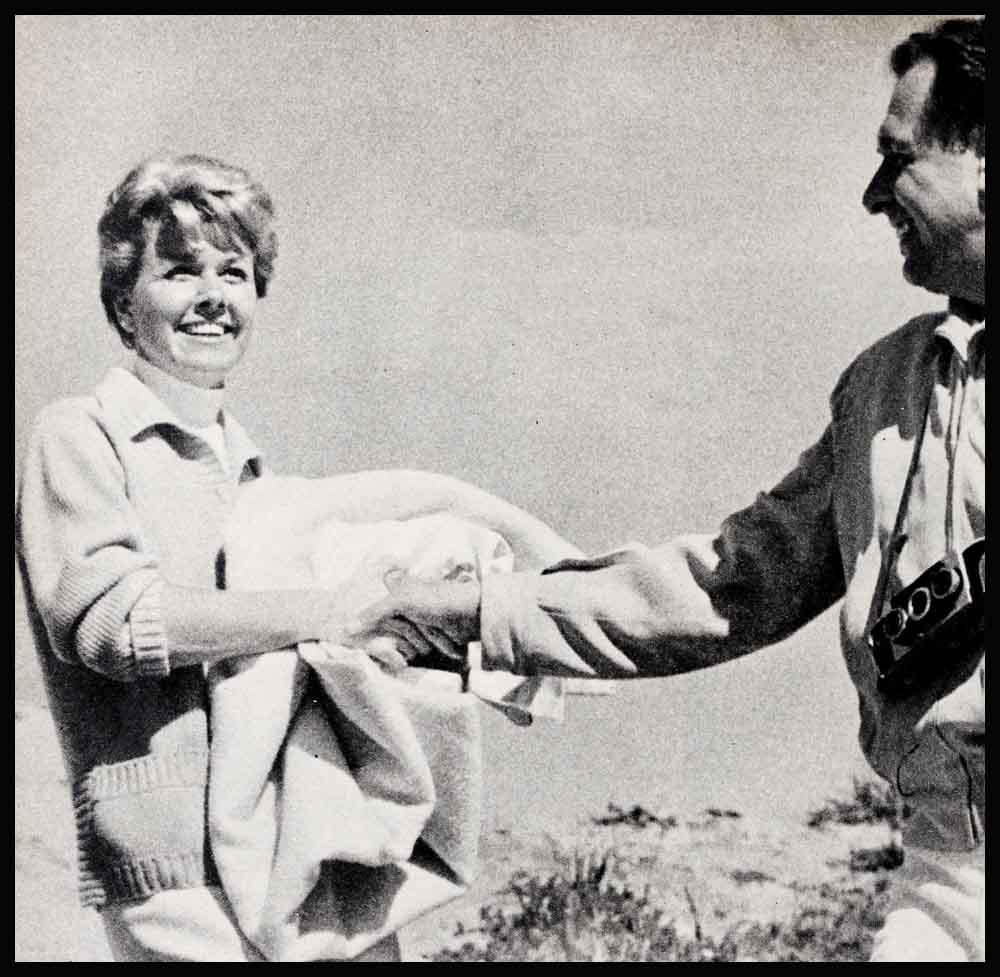

Thus, one recent day when New York was pretending to enjoy a chilling but meager snowfall, it was my great good fortune to he sitting with Doris Day on the sun-drenched terrace of the Beverly Hills Tennis Club. She was avidly licking a giant-size ice cream cone before it could drip on her freshly creased white tennis shorts. Beside her loomed her tall young son Terry, similarly engaged. Though the resemblance between mother and son is striking in photographs, in real life it is uncanny. From their dripping ice cream cones to the last one of their multitude of freckles, Doris Day and fifteen-year-old Terry were the licking images of each other, and handsome, too.

As long as the conversation dealt with tennis, a game for which Miss Day is finding time for once in her life, Terry, no mean player himself, was a willing listener. But when the subject switched to motion pictures, he wandered off toward the pool.

Having finished the ice cream, Miss Day munched on the rest of the cone, partly stalling for time, but mostly because she would have eaten it anyway. “About the whole story of my life,” she said at last. “I’m not really the person to talk about it, because I didn’t have much to do with it. Does that confuse you? It confuses me. But it’s true, in a way. Things just happened, and I had to go along.”

“Like in your song?” I was referring to “Whatever Will Be, Will Be,” the record-sales of which had passed the million mark, and were soaring toward an all-time high.

“Like in the song,” she agreed solemnly. “Que sera, sera. In just three words you have the story of my life.”

Before leaving New York for Hollywood, I had pored over the thousands upon thousands of published words concerning this girl’s life. What I had read certainly had not hinted at a summation so brief and so fatalistic. Quite the contrary. I knew that a lot of things had happened to Miss Day through no fault of her own; that there had been times when her life was so crammed with adversity and personal tragedy that it is a wonder she did not break. But I also knew that her courage and fighting spirit had carried her from rock bottom to spectacular triumphs not once, but several times. This had been a life of violent contradictions, so filled with high romance that her two divorces seemed to have never occurred; so filled with exuberant health that her long months of bedridden pain must have belonged to someone else.

So I said, “I can’t help feeling that this resignation, this fatalistic acceptance of whatever comes along, is something you have fought against all your life.”

“I suppose it does look that way,” she agreed. “But if we go into all that, it would mean—” She paused. She knew that it would mean going into memories long since stored away in pigeonholes built to be forgotten. It would take time, lots of time to tell it all. The afternoon was too pleasant, and there were too many people around who could not pass Miss Day without stopping to say hello. Sunshine, laughter, and a bright terrace blossoming with gaudy table umbrellas. A time for happy talk.

So we talked for a while about the easy things—the Doris Day of 1957. I asked, referring to some recent headlines in the trade cress, “Don’t words like ‘Wow,’ ‘Smash.’ and ‘Socko’ thrill you?”

“Oh, sure,” she answered. “I can never believe it’s really me they are talking about. I just feel glad for the girl in the picture who got a hit. You see, I can’t bear to look at my rushes or my pictures, so I don’t think I deserve it when nice things are said. It’s somebody else.”

She might be able to avoid seeing her rushes or her pictures, but there was one thing she could not escape, and that was her singing. She would hear her records on every radio station, on every jukebox and on every Street that boasted a record store, whether she was in New York, Calamus, Iowa, or Coronado Beach. She would hear them at house parties, beach parties and picnics, and on everything from thousand-dollar hi-fis to hand-cranked portables. Did she like them any better than her movies? What did she think of Doris Day, the vocalist?

“I like her,” she admitted frankly. “At first I didn’t think it was me singing, but then, no one ever really gets accustomed to hearing her own voice. I used to worry a lot when I heard myself. Some songs I might trip on several times before I’d get it just right, and then when I’d hear it on the radio, I’d start worrying that I might crack a note. I’d find myself straining, my throat getting all tight, trying to help the singer across the hard part. But now when I’m driving to work with the car radio on, I listen to Dinah Shore and Jo Stafford and Patti Page and Margaret Whiting—and me—and well, I just say, ‘Isn’t it nice to be in that company?’ ”

For the time being I could let the psychologists wonder why she could enjoy the sound of herself on a record and not the sight of herself on a screen. Because I was busy looking at the sweet, scrubbed freshness of Doris Day’s face. It reminded me of a review I had just read by critic Hollis Alpert. “No one,” he wrote, “has ever asked me to choose the typical American beauty, but if I were asked, I think I’d by-pass Marilyn Monroe, Kim Novak, Elizabeth Taylor and Sheree North. I’d pick Doris Day. It would be as easy as snapping a finger. . . . She’s authentic. She’s the girl every guy should marry.”

Just then the guy she did marry joined us, freshly showered after a session on the tennis court and obviously feeling good all over. He had seen the trade papers in the locker room. “You’re great!” he announced to his smiling wife. “A smash, a wow, a socko, a loud, hot and torrid hit. You did it, you did it, you did it! I’ll buy you a whole new box of Tootsie Rolls. And a whole bouquet of lollipops. All flavors.”

“You must have won your tennis match,” said Doris, unmoved by his generous flattery.

“Lost, as a matter of fact,” said Marty cheerfully. “But what about ‘Julie’ in New York? Did you do it, or didn’t you do it?”

“You did it,” said Doris firmly.

Marty turned to me. “Actually, Andrew Stone and his wife, and my wife, and Barry Sullivan, and Louis Jourdan and Frank Lovejoy—they all did it. Andy wrote and directed ‘Julie,’ and his wife Virginia was his assistant and film editor. Now there’s a husband-wife team that is going places.”

It was too good an opening to miss. “So why not the husband-wife team of Melcher and Day?” I asked. “Why no more ‘Julies?’ ”

“Different. Entirely different,” replied Marty promptly. Then he said, “Producers and actors come from opposite sides of the fence. They have to. A director can work with his assistant director and a writer can collaborate with another writer. But it’s tougher for a producer and a star to work together. It’s business against creative art. That’s where an agent comes in handy—to iron out the difficulties between his star and the producer. When I was Doris’ agent, I used to go to bat for her. When I became her producer I used to—Say, isn’t this a wonderful day?” he suddenly interrupted himself. “You don’t have days like this in the winter in New York.”

I had to admit it was that kind of a day, and definitely not the kind of a day on which a producer should squabble with a star when a handsome husband had a beautiful wife to admire. In fact, from the way he was admiring her, it was not the kind of a day they should have ruined by interviewers. So I remembered another appointment, made the necessary arrangements to meet again, and left.

It was Marty I met the next morning at the suite of offices occupied by his music publishing company on the Sunset Strip. It looked prosperous, if not downright opulent, and Marty was obviously proud of it.

“This is it,” he said. “This is the kind of business I’ve always liked. I like music, composers, lyric writers—the whole funny business. And every now and then a hit tune to stir things up.”

“Like ‘Whatever Will Be, Will Be,’ for instance?”

“A perfect ‘for instance.’ That’s Doris for you. And if you are still interested in that husband-wife team idea, music is one business in which we hit it off. We’re partners in one firm that just handles her music interests. But that’s one of the few places we meet in a business way.”

I was surprised. It was no secret that in the days before their marriage, Marty, as Doris’ agent, had handled everything for her, from leaky faucets to million-dollar contracts. “You’re not her agent any more?” I asked.

“I would say that I am her personal manager. MCA handles most of her contracts, and that usually leaves us free at night to talk like a husband and wife instead of about some clause buried down there in fine print. Let MCA or someone else worry about the fine print. Don’t forget, Doris is big business, and my getting too much involved in that isn’t good for us. Looking at her, you forget that every time she makes a picture or a recording, there are thousands of people involved, just as though she were a big factory. I remember when she starred in ‘April In Paris,’ there were nearly 3,000 people working on the picture at Warner Brothers alone, not to mention the thousands of others—theatre owners, projectionists, box-office girls, newspaper ad salesmen, ushers—who make a living out of theatres all over the world. Do you see what I’m driving at?”

“It’s hard to think of Miss Day as a big factory, but I’m trying.”

“Well, Doris used to say she could manage her business affairs by dumping her purse out on the table and counting the change. Now her business affairs are handled by the management firm of Rosenthal & Norton, and they have a big job or their hands. The point is, if we worked on her business affairs as a husband-and-wife team, we’d be working at it full time and what kind of a marriage would that make? It would be like being married to a Corporation.”

“Is that what happened on ‘Julie’?”

Marty considered the question gravely. “I’m glad we made ‘Julie,’ and I’m glad it looks like a hit. We proved we could do it, and that means a lot. But I don’t think that Doris and I are ideally geared to work together as star and producer and then carry all the pressures into our home life. Andy Stone had a lot of good ideas about using real settings instead of sound stages, and I had a few of my own, and I can say that we brought the picture in for about a million dollars less than it would have cost a major studio to produce it. As a partner in Arwin Productions, Doris admired us for that, but as the star of the picture there were some corners she would not allow us to cut. She was right, of course. You don’t get to be a star if you aren’t right most of the time, but still we had arguments.” He paused to reconsider a delicate subject.

“Now here’s the pitch,” he said at last. “In most businesses, when a husband-and-wife team win a point, they win it together. But in our case, if Doris won, I lost. And if I won, Doris lost. Now you take a situation like that home with you. instead of the star going home to get some sympathy from her husband, and the producer going home to weep on his wife’s shoulder, we’d go home together. And there, over a wonderful dinner, we’d sit, not too happy. You get the picture. Then one night we both started to laugh, and then we realized what was happening.

“It didn’t matter which one of us had won on the set. In the end we both had lost. We had lost a happy evening at home together, and man, it was because we wanted to be happy together that we had married in the first place. Our so-called teamwork was ruining the very thing we had teamed together for.”

I said, “So just when you were going good, you called the whole thing quits?”

“That we did. But, mind you, this is the way we happen to feel right now. We’ve been saying that we’d never do another ‘Julie.’ I’d like to restate that. If we go on thinking in the same terms about a star’s relation with her producer, then, chances are, we won’t work together again. But, who knows, we might see some new angles on the thing. In that event, we’ll review the whole case.” He smiled. “Nothing’s ever really definite in this business.”

“Anyway, look what happened,” he brightened considerably. “Doris got the starring role in ‘Pajama Game’ at Warner Brothers, and instead of having her poor husband for a producer, she’s got the great George Abbott from Broadway, plus Frederick Brisson, Robert Griffith, and Harold Prince. Four producers! We’re going to have a wonderful winter together.”

An intercom announced the arrival of a songwriter Marty had been expecting. He said, “Now that’s what I like about my business. This guy might have a hit that will sell a stack of sheet music the size of the Washington Monument. A million records. A theme song for a movie. Who knows?”

I left Marty’s office and took the six-mile ride from the Strip to the studios of Warner Brothers. I tried to picture Doris Day as the big Corporation whose product was beauty and talent. But was this the same girl I had met at the tennis club? The same girl who had been born Doris Kappelhoff in Cincinnati, the same girl who was a good wife and mother? I arrived at the studio thinking that there were several Doris Days, maybe a dozen.

I was just in time for lunch, and because Doris and I wanted to talk, we passed up the Green Room where the Warner Brothers’ stars and executives table-hop during the lunch hour. Instead we went to a quiet restaurant Doris favored. We had a roomy booth to ourselves.

Doris was wearing a simple white outfit that on anyone else would probably have been called a sports dress. But on her it seemed like one of those creations that are sheer inspiration. Her tousled blonde hair was pertly cut in short, casual pompadour fashion, and the wind had added some even more casual touches. Somehow, though, it looked as if each careless lock had been artfully placed by a master stylist. Doris was every inch the movie queen in the great tradition of the silent films, but at the same time, with her freckles and wonderful smile, she managed to be her friendly, untouched-by-Hollywood self.

Doris ordered her favorite pan-sized hamburger plus a huge tossed salad on the side.

“On this picture I can eat all I want,” she said with satisfaction. “There is a lot of dancing in ‘Pajama Game,’ and we’ll have to rehearse so much that it will be impossible to put on weight. Not that I have to worry about it. I guess I’m too active.

“We should have had lunch at home,” she went on, “but the place is a mess. We’re getting ready to move, you know. It’s a strange thing. Our house at Toluca Lake—we bought it from Martha Raye, and I love it so—was just fine because it was handy to Warner Brothers. Then when I left the studio to free lance, all my work was out in Culver City or far places like that, so we bought conductor Alfred Wallenstein’s house in Beverly Hills. It’s beautiful. Why, when I think back—”

“Yes?” I questioned with unsubtle eagerness.

“Nothing. Nothing right now, that is. But it does make a contrast.”

“From living in a trailer?”

“Oh, you’ve heard that story, too.” She made a slight grimace. “It’s true enough, and it got a lot of publicity for some reason. Lots of people live in trailers, and it can be all right, you know.”

“Was it?”

“Let’s work up to that part gradually. I’ll admit that was one of the unhappiest parts of my life, but it wasn’t the trailer’s fault. When you know more about me, why then you’ll understand.”

Now I do understand, but at that moment at lunch I felt slightly frustrated. For some reason I could not fathom, our interview was going in Doris’ direction and not mine. Now I know why, of course. All too often a star’s story is written in response to an interviewer’s questions. The star will answer honestly, but the interviewer asking one set of questions may end up with a story that will in no way resemble that of another interviewer asking an entirely different batch of questions on the same subject. To avoid that kind of conflict, we spent the rest of the afternoon in reaching an unusual agreement.

We would, we decided, let the unvarnished facts speak for themselves. The facts, not the question, would lead the way.

“It’s like this,” explained Miss Day. “I always do my best to answer questions honestly, but some questions come up more often than others. Then when I answer the questions, that answer is printed more often than others, and so it gets— well, let’s say it gets an emphasis all out of proportion to what it deserves.”

“Like, for instance?”

“Oh, that trailer story, or the time I broke my leg, or my two divorces, or that I am the child of a broken home, or about my being the bouncy, girl-next-door-type. They’re true stories, except I don’t get that ‘girl-next-door’ stuff, and you’ll see why. But their importance has been exaggerated. Like the time the Hollywood Women’s Press Club voted me their ‘Sour Apple’ as the ‘Most Uncooperative Actress of the Year.’ What I’d like your story to do, is put everything in its proper place, and let the reader find out why one thing led to another.”

“So where do we begin?”

“You might try Cincinnati,” she suggested. “Everything started there, and sort of keeps going back to there.” She paused and then said with remarkable frankness, “I was pretty young when I came to Hollywood the last time. Maybe the things I want to remember are only the good things, or the things that were good for me. Why don’t you get the other side? Talk to the people who had to put up with me and helped me along, and things like that. They know more about me than I know myself. I’ve told my own story so often, maybe I’m getting in a rut.”

Now we were getting somewhere. I knew that when Doris made “Love Me or Leave Me” at M-G-M, there had been a period of three months in which she cooperated with the press so fully that she averaged 200 interviews a week. It might well be that Doris had told her own story too often. All told, there had been 3,000 interviews during the filming, and when you figure that Doris has starred in some twenty pictures, the total comes out to be a lot of interviews. Just another insight into what it means to be a movie star. But that’s a different story.

As the umpteenth interviewer, I had to ask, “And who do I see in Cincinnati?” I reflected meanwhile that it’s a rare movie star that wants you to go to her home town to pick up the local gossip.

But already Miss Day was as chipper and eager as though she were going home for a visit herself. “Oh, you must see my Uncle Frank, and Barney Rapp and Grace Raine. And Will Lenay, and Danny Engel and Milt Weiner—the whole crowd. You’ll like every single one of them, bless them all.”

There were still many friends of Miss Day whom I wanted to interview in Hollywood—stars, directors, producers, character actors, extras, and neighbors. But she was right. To know the Doris Day of Hollywood only recently acclaimed by Motion Picture Exhibitor as the top box-office draw of all actresses, I had to know first the girl in pigtail braids from Cincinnati.

I was there the next morning.

So the story of Doris Day’s journey begins. Today she has reached a high plateau of happiness and success. But how did she come to it, and by what painful steps? Be sure to go on with George Scullin’s story in May Photoplay. (Doris is being seen in M-G-M’s “Julie” and Warners’ “The Pajama Game.”)

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1957

AUDIO BOOK