A Character—But Still Brando

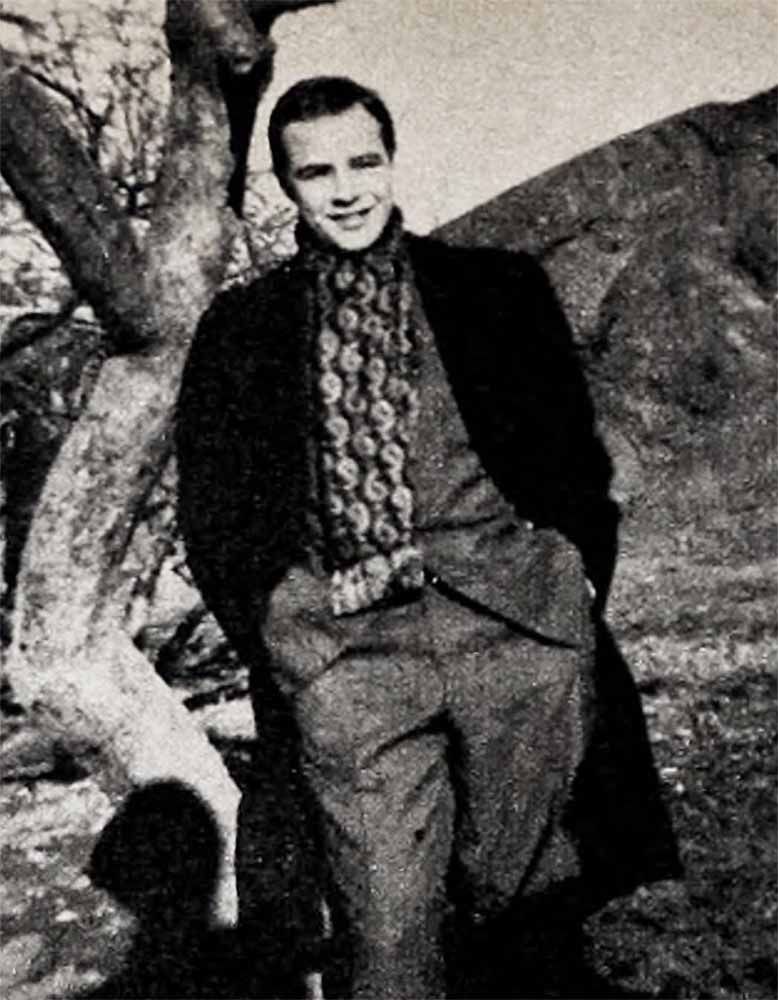

Scrambling along a jagged rock ledge in New York’s Central Park, a well-dressed young man in a blue-gray business suit, super-white shirt with button-down collar and subdued knit tie turned sharply to the three girls running after him and yelled, “Come on, the view’s terrific.”

Even a few blase New Yorkers turned and chuckled as they saw the enthusiastic young man perched high on a rock pile. He looked as though he had just achieved the remarkable feat of climbing Mount Everest.

Other folk may have recognized him to be Marlon Brando, and said to themselves, “that guy Brando’s a character.” This is hardly so to the people who know him, like the three fans who scurried after him in the park. To them, he was a great actor, kind of a hero—and a friend—and they joined (at his request) in his plot to work off some energy with just as much enthusiasm.

“Now that you come to think of it, we might have looked a little funny,” says Philomena Ignelzi, who is president of the Marlon Brando Charity Fan Club. “But it was a beautiful afternoon and it just seemed like the natural thing to do. Which is one of the most wonderful things about Marlon. He always makes you feel natural and relaxed. He knows how to bring you into things and into the fun. And as you can imagine, Gertrude (Heim) and Patricia (Mulqueen) and I were pretty nervous about the whole idea of meeting him.

“It all started one evening last January. I had just gotten home—I had an evening class at Hunter College that night—and Mother had kept some food warm tor me. I was just sitting down to eat when she casually said, ‘A young man called today and wants you to get in touch with him.’

“ ‘Who?’ I muttered rather disinterestedly, tired from the long day.

“ ‘He says his name is Marlon Brando,’ Mother answered, trying with all her might to keep calm.

“ ‘Marlon Brando,’ I screamed. ‘You’re kidding,’ ” and I couldn’t eat another bite. To boot, he’d left his telephone number for me to call him back!

“The reason Marlon knew of me was that I’m the president and one of the founders of the Marlon Brando Charity Fan Club, and I’d recently sent him a copy of our first club journal. It took quite a few phone calls back and forth (I was a nervous wreck), before we reached each other. But when we finally did, he was very interested in the work we were doing and asked all about us. He said he liked our journal very much and fully appreciated and approved of the charitable work we were doing on his behalf and in his name. Then he asked, ‘I’d like to meet you and some of the other girls in the club. Could you make it?’ Could we! ‘We’d love to.’ I answered. So he suggested we call his secretary and ask her to set a time since ‘she’s the one who keeps track of my engagements.’

“Miss Medwick, Marlon’s secretary, made a date for three of us to meet him for lunch at one P.M. the next Saturday at the Russian Tea Room on West Fifty-seventh Street.

“I’ve been a real ardent Brando fan for fully five years, ever since I saw him in his first movie appearance in ‘The Men,’ and I’ve seen every one of his pictures. In fact, ‘Viva Zapata!,’ my favorite next to ‘Waterfront,’ I’ve seen five times. So the thought of finally having lunch with him was exciting beyond measure.

“I had met Marlon once before. During the summer of ’fifty-three I traveled to Ivoryton, Connecticut, one weekend to see him in a summer stock performance of Shaw’s ‘Arms and the Man.’ Marlon was playing Sergius (and getting rave reactions). It was a wonderfully funny part, in fact, Shaw had called Sergius ‘my comic Hamlet,’ and Marlon was terrific. I arrived early and was waiting on the lawn outside the theatre when I saw Marlon drive up with a bunch of his friends in an old car, get out and go into the small near-by restaurant. While one of the fellows was taking some props out of the trunk of the car, I went over to him—quite timidly—and asked if he could introduce me to Marlon after lunch. He said he’d see what he could do.

“When finally they finished eating and came out of the restaurant, Marlon was immediately surrounded and I figured that was the end of my chance to meet him.

“But I was wrong. While still talking to the group, Marlon looked up and around, then said something to the boy I had talked to. He took me right through the cluster of people and introduced me to Marlon. I was very impressed with Marlon’s courtesy, his sincerity and his genuine interest in the people around him.

“Henry Josten, who’s the local newspaperman, summed up the local opinion of Brando with ‘he’s one actor who’s completely down to earth. No prima-donna airs about him, no superiority either. He’s a friendly, warm person, and I feel we folks around here probably have gotten to know the real Marlon Brando better than anyone in Hollywood or even New York.’

“The following winter I finally plucked up enough courage to write to Marlon and ask him for permission to start a Marlon Brando fan club that would be devoted to charity. His reply in longhand:

Dear Philomena:

To be plain, I am totally indifferent to fan activity and all that. You mention that there might be some connection between the fan club and charitable work.

If my name could be lent to any (but strictly charitable) work, I happily and willingly donate my name, for whatever it is worth, to the purpose of establishing an organization devoted to charity.

I wish you the most complete success in your plans and future

Sincerely yours,

(signed) Marlon Brando

“When we finally met Marlon at the Russian Tea Room, as he had suggested, Marlon was a little late. The first words he said, while joining us at the table his secretary had reserved, were, I’m terribly sorry—I was held up. I hope you haven’t been waiting long.’ (He was a far cry from the jeans and T-shirt type he’s accused of being. His diction and voice are pure and distinct and he was dressed in a neat gray suit—with tie!)

“I introduced myself and Gertie and Pat. We were afraid, beforehand, we’d be too tongue-tied to do much talking, but nobody has a chance to be shy around Marlon for very long. Before you know it, he’s asking you questions about where you live, and what kind of work you do, about your family and about your club work, and you’re laughing and kidding, forgetting all about your earlier fears.

“When it came time to order we weren’t very hungry. I guess we were too nervous, so we ordered sandwiches. But Marlon wouldn’t hear of us eating everyday American food in a Russian restaurant.

“ ‘You don’t want to eat a sandwich,’ he said. ‘You must try some of the Russian specialties on the menu.’ And then, very patiently he helped us select some of the foods that were his favorites—since we didn’t know anything about Russian food. He insisted that we try the Borscht, then ordered specially prepared steaks for us. He, himself only ordered scrambled eggs and coffee. I was sitting there, kind of toying with my bowl of Borscht. Seeing that I had hardly touched it, he merely pulled the dish over in front of him and finished it himself. There’s no nonsense about Marlon!

“Marlon was genuinely interested in the kind of work the club was doing. We told him about our various projects of sending get-well cards to people who are very ill and badly in need of a little boost for their morale and of collecting, repairing and sending toys to children in hospitals. When you talk to Marlon, he listens very carefully and looks at you with such interest that you cannot help feeling that what you say is very important to him.

“ ‘Wouldn’t it be great,’ he said finally after listening to us talk, ‘if we could raise enough money really to help? And not just help the ones who are sick. Imagine if we could send new clothes to a little girl or a little boy who really needed them. Think of how they must feel having to go to school in ragged, hand-me-down clothes.’ He promised to help us in any way in our work and even suggested a fund-raising ball. Marlon’s very much interested in social work, and I’m convinced that he never would have lent his name to any fan club activity if it weren’t for charitable purposes.

“As a result of my talk with him, I started devoting one evening a week to a Cub Scout den of the East Side Settlement House, which is all I can sandwich in between club activities and going to Hunter College night school. But I hope to do more for, as Marlon explains, we can all contribute to helping others—we don’t need big names or important contacts or lots of money—just a little sincerity and a little of our time.

“But to get back to lunch. When we were through with coffee, I asked Marlon if he would autograph a photograph I had brought along.

“ ‘That’s a terrible picture of me,’ he said laughing.

“But I told him I liked it very much and he said ‘That’s all that matters.’ He inscribed it: ‘Dear Phil, If it weren’t for you a lot of people would be a lot less happy. That’s the best I could hope to say about anybody. With gratitude, Marlon.’ I’m very proud of that inscription.

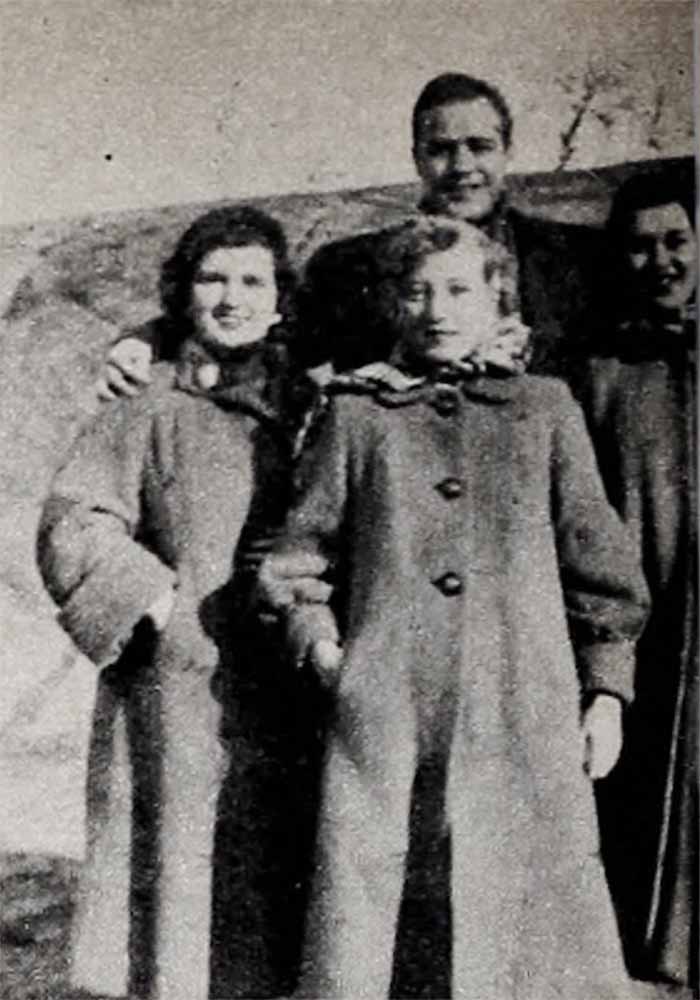

“During lunch, Marlon had asked me to put my own picture in the next journal. I told him I’d only do that if he would be in the photograph, too. ‘Sure,’ he said without hesitation. ‘Too bad we don’t have a camera with us. We could do it after lunch.’ With that, up came two cameras, till then hidden underneath the table.

“We left the tearoom—walked over to the park and took a whole roll of pictures. Marlon, of course, knew a lot more about photography than we did so he’d pick out the spots and help us with the lighting. We spent the afternoon in the park, walking and climbing up the rocks. Altogether, Gertie, Pat and I agreed—it had been a beautiful afternoon—and it wasn’t just the weather!”

A long-time friend, and just as staunch a Brando fan, is Stella Adler—who has known Marlon ever since he first arrived in New York in 1941, a teenager from Libertyville, Indiana, and applied at the Drama Work Shop of the New School. While Miss Adler won’t credit herself with foreseeing Marlon’s outstanding career from the beginning, she can be quoted as having said, after one week of instructing him, “This puppy thing will be the best young actor in the American theatre within a year.

“What people don’t seem to understand about Marlon,” Miss Adler said one afternoon in her school at 50 Central Park West, “is that he is an actor. When he studies a new part, it is an intensely Creative process with him. Louis Calhern once made the remark that on the set of ‘Desiree’ there was a guy by the name of Napoleon who thought he was Marlon Brando. I think that can be said of Marlon whether he plays the poet Marchbanks in ‘Candida,’ or the ex-pug Terry Malloy in ‘On the Waterfront,’ or Sky Masterson in ‘Guys and Dolls.’

“Marlon’s an actor twenty-four hours a day. I’ve heard it said that anyone as intense as that must be a schizophrenic, a split personality seeking escape from his own identity by assuming another on the stage. I’m no psychiatrist, but to me that doesn’t make much sense. I believe that most people who have a talent, a vocation in life and who do a job superbly well, don’t just work on it for eight hours a day, but carry their work with them wherever they go. With Marlon, everything he sees or does, every person he talks to, every contact is grist for his mill. After watching a person for two minutes, Marlon can imitate him precisely. He constantly observes. He constantly studies. This isn’t necessarily a conscious act, for the truth is, Marlon isn’t very good at any methodical studying. He’s like a sponge—he seems to absorb information and knowledge through his pores. I’ve known Marlon for a long time now, and he’s never impressed me as being anything but a perfectly normal, highly talented young man.

“And I emphatically won’t go along with people who say Marlon is eccentric. He’s high-spirited and full of fun—perhaps a little reckless at times, true—but he’s always been very young and I don’t particularly see where this makes him so different from millions of other American boys. He’ll go off on a kick—from playing the bongos to boxing, fencing, interpretive dance and riding a motorcycle. When he was on his motorcycle kick I was worried about him because I was afraid he might get hurt, but this is, after all, his own business. After he learned all about motorcycles, he outgrew them. Besides, he needs an outlet for his energy. Marlon can never sit still for any length of time, he’s so full of energy, a kind of nervous vitality. But one thing is true, he’ll take a chance or a risk only when he alone is involved. I’ve never seen him—or heard of him—doing anything that might harm someone else. He’s always very considerate of others and he’ll go out of his way to do a friend a favor.

“Once he went forty miles—’way out to Long Island—to surprise me. It was during his motorcycle period, and I’d casually mentioned a special kind of pastry I liked which only seemed to be available at one bakery on the south shore of Long Island. The next time Marlon came up to the house he brought some of that pastry with him. He’d gone all the way down there and back just for a dollar and a half purchase.

“Contrary to legend, Marlon is always dressed very neatly when he comes visiting. He’ll wear a T-shirt and a baggy pair of pants when he goes to rehearsals—but then so does everybody else. Also, I’ve never known him to be anything but well-spoken, well-mannered and well-behaved.

“It would be surprising if it were otherwise in view of his fine family background. Marlon’s father is a sucessful Illinois businessman; the Brandos had a comfortable home and a very pleasant family life. You’d have to look far before you’d find a nicer all-around American family. all the Brandos are very Creative people with an interest in the arts. Marlon’s mother, who passed away about a year and a half ago, was at one time an actress with the community playhouse of Omaha, Nebraska, and a very beautiful, girlish creature. His sister Frances is a painter, and kid sister Jocelyn, also a talented young actress, best remembered for her role in the play ‘Mister Roberts.’

“And Marlon always went to good schools—several of them. I guess Marlon didn’t get along any too well in school. At his last one, Shattuck Military Academy in Minnesota (‘the military asylum,’ he called it), he was caught in a prank and asked to resign shortly before graduation, in 1943. During the following summer he worked as a tile fitter for a drainage construction company in his home town of Libertyville, Illinois. For all I know, he might still be doing that if his father hadn’t offered to stake him to a professional education. Marlon decided on acting and came to New York that fall to live with his sister Frances, who was studying at New York’s Art Students League. (He worked four days at Best & Company, balked at calling out ‘lingerie’ and such things and quit.)

“One of the things few people realized about Marlon is that he’s quite without drive. Success as such doesn’t mean a thing to him. He has no desire to outstrip his competitors. While he appreciates money, it is certainly no end in itself for him. I think Marlon would be a failure if he tried to do anything that doesn’t deeply interest him—or rather, I don’t think he’d make the effort.

“With acting it’s different, of course. He broke through very quickly, and from that moment on acting got under his skin. His performances in the drama workshop of the New School attracted attention from the very first. It wasn’t difficult for a professional to see that he showed a good deal of promise. For one thing there was his great physical beauty—not just good looks, but that rarer thing that can only be called beauty. And for another, he had a quality which in the theatre we call ‘visibility.’ It’s a sparkle—a gift of God—there’s no explanation for it. Without doing anything, it made him stand out in any group. The eye would just naturally travel to him and stay there.

“As a drama student—whatever his shortcomings may have been in other schools—Marlon was very easy to get along with. He was disciplined and serious, and if he ever did cut up, it never reached a point where it interfered with our work. I remember one rehearsal when nothing seemed to go right and everybody was becoming irritated and tense. We were doing a scene from ‘Ghosts,’ by Ibsen, with Marlon taking the part of the tragic young hero. When he made his entrance, he was wearing the most fantastic putty nose I’ve ever seen. Everybody was in hysterics for about five minutes, which relieved the tension, and afterwards the rehearsal went well.

“In this respect, Marlon is a real ham. He loves to fool around with make-up, putty, false noses, beards and wigs. And he has a wonderful ear for inflections and accents, along with a natural gift for mimicry.

“Marlon has no difficulty at all in imitating all kinds of voices and accents. When my husband and I ran into him in France one summer he surprised us by the beautiful French he spoke. He was easing himself into the language the way he eases himself into a part. He sounded like a Frenchman. He picked up a working knowledge of Spanish in two weeks. He’ll never call up the house without disguising his voice. I confess that after all these years he still succeeds in fooling me each time, whether he puts on a British, Mexican, Italian or plain Midwestern accent. I think that’s a measure of how good he is.

“I remember how surprised critics were when he spoke with perfect diction as Mark Antony in ‘Julius Caesar.’ They failed to realize that he had to learn to talk like Stanley Kowalski in ‘Streetcar,’ that he did not normally speak that way. After all, one of his earliest parts on the professional stage was Marchbanks, opposite Katherine Cornell in Shaw’s ‘Candida.’ He spoke beautifully.

“Perhaps Marlon’s nicest trait is his loyalty and devotion to his friends. During the twelve years I’ve known him he hasn’t to my knowledge dropped a single one of them—nor has he lost any. Unfortunately, that is not always true of others who have become successful so quickly.

“Another thing which is well-known about Marlon is his gentleness. In the mind of the public Marlon’s become identified with tough parts, implying a degree of brutality that’s entirely foreign to his real character. Actually, he’s a real softie who can’t bear to hurt anyone’s feelings.

“Once I sent him a play written by a young friend of mine. ‘How did you like the script?’ I asked him the next time I happened to see Marlon at a friend’s house.

“ ‘Terrible,’ he blurted out, not realizing that the author was standing right next to me.

“Though it had really been my fault for putting him on the spot, Marlon was inconsolable. He was remorse-stricken for weeks over what he considered his unforgivable lack of tact.

“I can say, though, that there’s one thing Marlon can’t do well. That’s lying. Not too long ago, he came up to the house with a beautiful shiner around his left eye. When I asked him about it, he was ashamed to admit the reason and concocted some cock and bull story instead. I didn’t believe him for one minute and he knew it. We both started to laugh. He can never keep a straight face when he’s lying. Yet he’s marvelous at telling a story, exaggerating and embellishing it for dramatic effect. This is probably where a lot of the Brando stories circulating around can be traced to, but Marlon doesn’t consider this lying, it’s all part of acting, of telling a good story.

“When you’ve known Marlon as long as I have, you can discern between the two and know when he’s pulling your leg. But in the meantime, if you’re trying to puzzle him out, the important thing to remember is that you can’t judge him as you would a businessman, think of him as a Bohemian intellectual or classify him as a matinee idol. He is none of these—by his own choice. Marlon is an artist—a great artist. People may call him a character, but he’s still in reality just Brando.”

THE END

(EDITOR’S NOTE: The Marlon Brando Charity Fan Club works with fans throughout the world. If you want to know more about the activities of this club, write to Miss Philomena Ignelzi at 149-41 45th Avenue, Flushing 55, New York, sending along a self-addressed stamped envelope.)

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1955