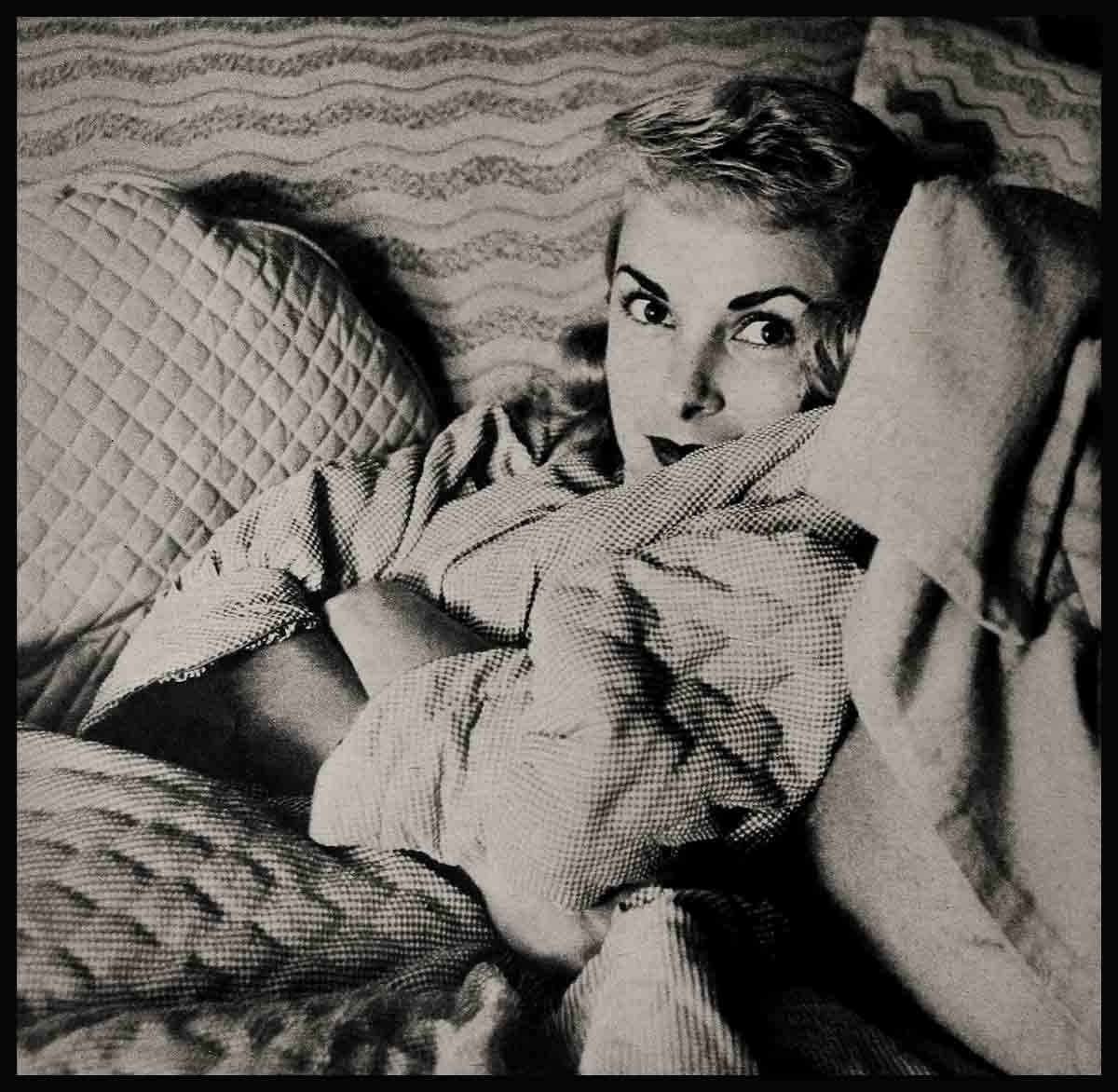

How I’ll Bring Up My Baby—Janet Leigh

It was funny, Janet Leigh reflected, sitting in the sun a few weeks before the baby was born—funny the way she hadn’t thought of a name for the baby. She and Tony just referred to it as It, or sometimes he, or sometimes she. It was proof that neither of them really cared whether it was a boy or a girl. She was sure she didn’t, and Tony was too happy about becoming a father to care one way or the other. If it was a boy, she thought, she’d be all right as a mother. She’d been a tomboy herself, and could always substitute when Tony was working. She wondered if she could still throw a curve ball.

He would—she would—it was so awkward not having a name ready. But then neither of them wanted a name right away. It would be like talking about a part in a picture before you really knew you had it. She supposed they’d end up with a Biblical name. They were substantial names, and not frilly, and they had worn extremely well through the ages. Frilly! She laughed, as her thoughts moved to lace and polka-dots.

Clothes would be their weak point, as parents, all right, even if it was a boy. She remembered the father and son she had seen in that men’s shop, and how they had walked out wearing identical gray flannel suits. That would be Tony, with his mania for clothes. He’d have a ball buying clothes for a son. And if it was a girl, what things she would have! That would be her own department, the ruffles and ribbons. But they mustn’t spoil this child. To give children nice clothes was one thing, but to lavish them was another. This baby must grow up knowing the value of a dollar and that life, while secure, is not necessarily, a bed of roses. It would be so hard to find the middle road.

When she was a little girl she had felt the lack of clothes. She loved them so and never felt she had enough. Not like the other kids in school. Her own daughter must never feel that lack, but then again, she must learn that nice things don’t grow on trees. You must work for them, you must deserve them. Well, maybe the child would inherit her own money sense. When she was only twelve and was given money at Christmas, she had managed to wait until the January sales before she went shopping. She figured that was pretty unusual for a child of twelve. And it had always been clothes. She remembered the time she was seven or eight and had won a contest as a drum majorette. She was to receive a prize and they had wanted to get her a bracelet or a ring, something that would last as a memento. But she had been wanting a raincoat and had insisted that’s what her prize must be. Let’s see, it had been green plaid, and there had been a hat to match. And then when she was older she had worked in the five-and-ten after school and on holidays. Yes, she’d had sense about money, all right. But what if the child inherited Tony’s genius for spending? Tony always wanted to buy the world for everyone he loved. And Tony loved so many people. Well, you certainly couldn’t say that was wrong. The baby should have some of that generosity.

And another thing, this baby was going to get one big lesson in life from his father. Tony had always said he would teach his children that the most important thing was to love people. This baby would know that soon. All you had to do was live in the same house with Tony, and it rubbed off on you.

She hoped the baby would have Tony’s enthusiasm for life. Then again, maybe Tony’s enthusiasm should be tempered a bit with some of her own practicality. If the baby grew up just like Tony, she’d have to spend half her life pulling them both down out of the air. A new thought struck her and she laughed softly. What if this baby were a girl, and a perfectionist like herself? Tony had a hard enough time living with her and her clean ash trays, but two women like that in the house would be too much for him.

On the other hand, suppose the child was hampered by Tony’s inability to say no. Then her life would be in an uproar. Not one, but two people saying sure, they’d speak at the club luncheon—or have the Women’s African Violet Association for tea, or giving away clothes they hadn’t worn yet.

But she hoped Tony’s talents would be handed down intact. Tony was so facile. He could do and learn anything he wanted to. She appreciated painting, but she couldn’t paint. She loved to listen to music, but she couldn’t create it. He had so much artistic ability, and this would be wonderful in a child. As for what she might give it, maybe it would have her love for singing and dancing. And she hoped it would have her nose. She wondered briefly if anybody would object to her saying that. After all, it was a pretty good nose. But it should have Tony’s hair, dark and curling, and his eyes and lips.

Janet looked down at her lap. There was a book lying there, and she hadn’t even opened it. She sighed happily. It was obvious she wanted to think about the baby, and why shouldn’t she indulge herself? There had been all those months of feeling rotten, and during that time she couldn’t even think straight. But now she felt she could beat her weight in wildcats, so why not take time to think, if she wanted to? Tony wouldn’t be home for a while, and there was nothing that had to be done. He must be so relieved that she was feeling better—he had been a tower of strength when she was sick, and if he worried he hadn’t let her know it. He really was holding up quite well. But then, they weren’t children any more; they’d been married for five years. There was no sense getting hysterical over having a baby. Lots of people had babies. And it was wonderful. It made you feel complete, it filled the future.

Not an only child

This one wouldn’t be the last baby, she hoped. She was an only child herself, and she’d been lonely. She had read a lot, but you can’t read all the time when you’re a child. Oh, she could entertain herself if she had to, and it had been fun on rainy days playing store by herself and making out those endless shopping lists. But it would have been more fun if there had been a brother or sister to play with. She’d seen the love and enjoyment Tony got from his brother, and it was a heart-warming thing to watch. No, God willing, this mustn’t be an only child. One would be easier to bring up, perhaps, because you could give it more attention, but then was that really a good thing? Large families always seemed to have better-behaved and adjusted children, and maybe it was because the parents had less time to fuss over each child.

Heaven knew she’d been fussed over enough. By now it was a joke between her and her mother. After her hair was washed she’d been made to wear two hats, to be certain she wouldn’t catch cold. And she didn’t remember it, but she’d been told about the time her mother was preparing to bathe her, as a baby, and had the house so hot it was practically steaming. A neighbor had come in and realized her mother was about to faint, and had to take over with the temperature, the bath, and her mother. There was no doubt about it; she’d been overprotected. That was the trouble with an only child. You had nothing else to think about and kept looking for possible dangers. If you were forever telling him to be careful, to look out, and not to do that, he might grow up scared to death to take a step for himself.

l was a nau-gh-ty girl

Except that, on second thought, it hadn’t worked that way with her. Maybe it was because she had been stubborn, maybe it was because she was self-sufficient; whatever the reason, she had never been timid, she hadn’t grown up into a Polly-sit-by-the-fire. On the contrary, she’d been disobedient.

She hadn’t been allowed to even ride home from school in cars, or date like the other kids, and she had resented it. She didn’t drink or smoke and didn’t want to stay out late, but she had wanted to do some of the things the other girls were allowed to do. So she’d chafed at the bit and ended up doing things she wasn’t supposed to. When she was wrong, she knew it, and it bothered her conscience.

She’d never blamed her mother for it. The problem had been that she was the youngest in her class. She had skipped three half grades, so all her school friends had been a year or two older than she was. So it had been hard for her mother; it had made a problem for both of them. If this baby were given an opportunity to skip a grade in school, she wouldn’t allow it. It made too many emotional problems for a child. If they were bored in school as a result of being held back, you could always fill in the void at home. You could give them piano lessons, or teach them to paint—Tony could do that—or have them tutored in a language. And in the meantime they’d be growing up with children their own age.

She thought Tony would agree with her on this. She couldn’t foresee his disagreeing with her on very many things about bringing up the child. Not the important things, anyway. They’d give it love, and they’d give it discipline. She wanted to get a pile of books on child rearing, but she wasn’t going to swallow them verbatim. It was a matter of applying the advice to the individual child. She’d take what she wanted from each book, and she wasn’t going to agree with any of that modern theory about never crossing a child. She’d cross it all right, if it did something wrong. There was a lot to be said for common sense, too.

She couldn’t see any reason why this baby wouldn’t grow up with the same sense of family closeness she had had. Her parents had given her a great deal of that. True, there had been the tug of war all the time about the privileges she felt she was denied, but what fun they’d had as a family! There were the weekends when the three of them would get in the car, planning a trip to nowhere. They’d end up in Santa Cruz or some other place—it was always a surprise—or they’d go on picnics together. And there were the days her parents had taken her and the whole gang to the football and baseball games. She was sure they’d done all that to make up to her for the lack of other things.

She hoped this baby would like school. She had loved it so much, whereas Tony had resented every day of it. Oh, he could get excited about Daniel Boone or Alexander the Great, but dates and trivia bored him. It was a matter of his application. He could then, and still could, get wrapped up in anything that interested him and do a job to perfection, but nobody could drive him to doing something he disliked. She, on the other hand, went too far overboard in the opposite direction. She tackled a job as a matter of discipline, and put even more effort into it if she didn’t like what she had to do. The baby, for its own sake, should be fifty-fifty on this score.

Well, whichever way this baby was put together, she and Tony would allow it to have its individuality. She wouldn’t force it into anything. She’d expose it to all the things its parents were still learning to appreciate—the art and the music and the good books and the gracious living. And the friends who were well-versed in so many interesting topics. But expose was the word, not cram. And this baby could pick and choose what it liked. She hoped that all during its growing-up period she and Tony would be able to give it these advantages. There would be college, if the child wanted it. And maybe education in Europe after it had finished formal schooling here.

Starring Somebody Curtis

But there she was, pushing already. She and Tony mustn’t make the same mistake with the child that they had made with each other. Always pretending they enjoyed every single one of the other’s interests, when they didn’t really. They had learned, but it had taken three whole years. There is such a thing as closeness, but it mustn’t become suffocating.

Yes, she would let the child go its own way, but she couldn’t help wondering if it would choose show business. If the answer was no, she wouldn’t care, as long as he or she was happy—and if the answer was yes, it would be fun. And sort of nice, too, when she and Tony were old and gray, to go see a play or a movie starring Somebody Curtis. Heaven knew show business had been kind to them.

A shout echoed through the halls and out into the garden, and Tony was standing there, grinning at her.

“Hi,” he said. “What’ve you been doing?”

“Thinking,” she said. “About what the baby will be like.”

He walked over and kissed the top of her head. “You got it all settled?”

She nodded.

“Just one thing,” Tony said. “If it’s a girl, don’t ever let her see you cleaning an ash tray before I’m through with it”

Janet laughed. “I’ve got that settled, too,” she said.

THE END

—BY JILL RAWLINGS

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE AUGUST 1956