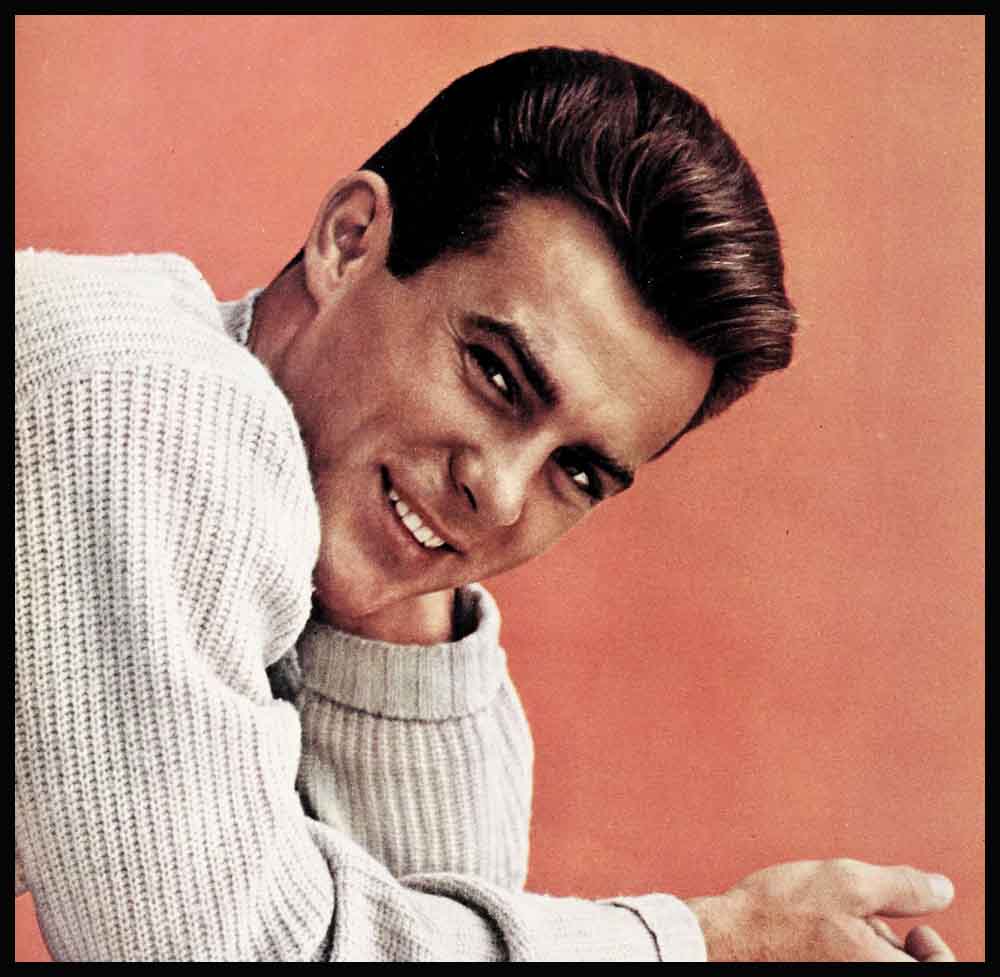

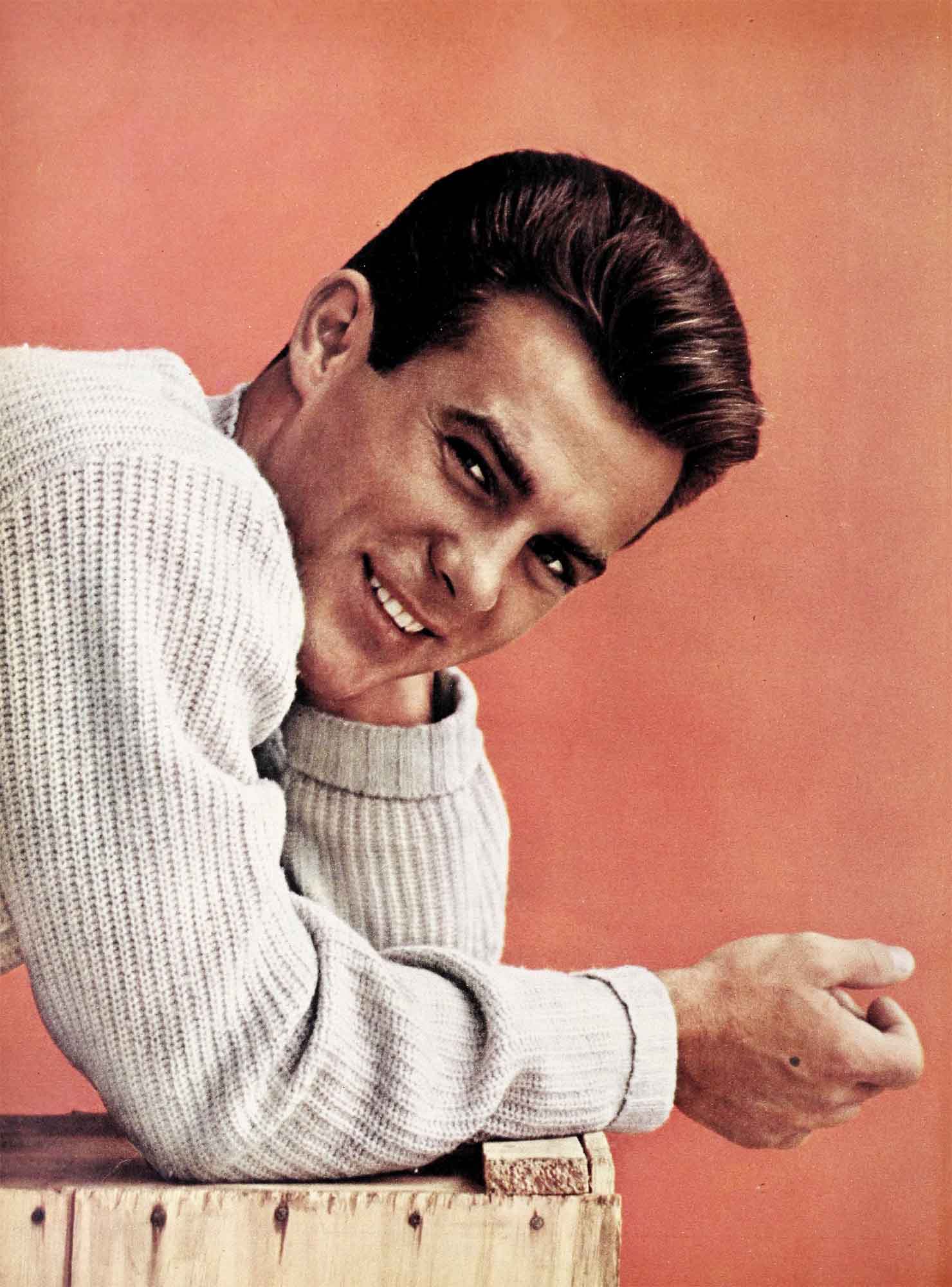

Read Robert Conrad’s Story

Something happened to him that summer when he was sixteen. It made him take a long look at himself.

“I’ve got to change,” he thought desperately. “I’ve got to be somebody. Even when I ran away from home to make something of myself, all I made was a big flat flop of it.” He was remembering how he’d stood by the road with his thumb out, while the cars whizzed by. He’d made it to Minneapolis and then, broke and defeated, he’d had to phone his mother for help. She wired him plane fare home to Chicago and she was nice about it. So was his stepfather. But their niceness made him feel more than ever how he longed to be like them—successful, brilliant people. He hated being a school-kid while his buddies, all older, were already in Korea—soldiers and men. But he? He was too young—he had to stay home.

There wasn’t a thing his mother and stepfather wouldn’t do for him. Music lessons, voice culture—whatever he wanted, Conrad Robert Falk could have. But the more they lavished on him, the more he felt he had to get somewhere on his own. Because that was what a girl like Joan Kenaly rated.

Joan Kenaly was the great thing that had happened to the boy this sixteenth summer. Joan and love. And it killed him that he’d found his girl just in time to lose her.

“Do you have to go to Florida?” he pleaded. “It’s a million miles from here.”

AUDIO BOOK

“What can I do?” she mourned. “That’s where Daddy wants to live.” Her father was retiring from a fabulous law career in Chicago. Another somebody! And Joan, herself, was terrific. The prettiest sixteen-year-old and the smartest student in Sacred High Convent. Knowing her, changed his whole world. He wanted to grow up immediately and be a man for her, because he loved her. And because she never asked anything but to love him in return.

Joan whispered, “I don’t have to go with my folks right away. They’ll let me finish out the year at the Convent and then join them.”

A little hope flickered. something,” he said. half a year yet.”

They were sitting in a booth at the sweetshop where they always met after school. They sat on the same side, so they could hold hands and talk low. To the adult world, they were a pair of kids in love with love—“puppy stuff.” But the boy knew that the biggest thing in his life was to grow up quickly, so he could marry Joan and take care of her forever.

The Kenalys went to Florida, and now every time Bob and Joan met, their heads were closer and their whispers lower. They could talk of nothing but the decision they hardly dared to make.

But they made it. A month before his seventeenth birthday, they eloped. On February 23, 1952, he became a man with a wife to support. Head of a household! After the first shock, that was the way both families played it too. The youngsters wanted to be independent, financially and every which way—and their families let them. It was their privilege.

And, somehow, it worked. He went out and got himself a job at a dollar and eighty-six cents an hour, as a dock worker for a trucking company. By putting in long hours he could swing the expenses, including sixteen dollars a week rent for a furnished apartment. For the first time he felt he had some control over his life. He began to feel he could do better than the dock job. And it felt good.

“I wish I could study voice again,” he confided to Joan. And his little-girl wife asked serenely, “Well, why can’t you?”

The family grew

With her encouragement, he switched to a night job, took vocal lessons by day, and still supported the two of them comfortably. When he was hired as vocalist for a brand-new band, at five dollars a night, he felt he was making a start. He sang at college dances, business banquets—until the band broke up and it was back to the docks for Bob. Besides, the family was growing. Little Joan was born on the next New Year’s Eve, and by the following Christmas, a second child was well on its way.

“It’s going to be the best Christmas of my life,” Joan told him happily. She was full of plans. They’d put up a big tree this year, even if Joanny was only a baby she’d still love it. “I saw the darlingest toys for her,” Joan said, “and I’ve got your surprise picked out.” Then she added with a laugh, “I’m just waiting for your next pay check, to make like Mrs. Santa Claus.”

“Listen,” he pleaded kiddingly, “leave me a few dollars to buy your presents, will you?”

“Christmas is for children,” they kept telling each other, proud of their parenthood, but they were merry as a pair of kids themselves. Until next pay day. And then he came home with dragging feet and a face that had so much trouble written all over it, he couldn’t hide it. Finally, he had to tell her. But it was hard to say. Instead, he pulled the envelope out of his pocket and handed it to her. And she saw what was in there along with his pay. A pink slip! “Yep,” he said gloomily, “that’s what I got for Christmas—fired!” And, as if he was afraid she’d think he was no good on the job, he said, “They had to cut down—there just isn’t enough shipping this time of year.”

Her arms went around him, consolingly. “Well, of course, Hon, or they’d never fire a hard worker like you. Look, let’s not worry. You’ll get something else soon.”

“You’re sweet,” he murmured, and held her close. But even her sweetness couldn’t keep the old, “I’m a nobody” feeling from creeping back into the very marrow of his bones. “A fine flop I am,” he kept brooding. “I can’t even provide a decent Christmas for my family.”

It was a tough time to feel so low. Every store window glittered, every sign said “Happy Yule” in letters ten feet high. The world was celebrating, everybody felt fine—except him. Every day he went through the “Help Wanted” pages and ran around job hunting.

Finally he found something, an ad calling for a “driver-salesman,” which translated into a milkman’s route. But that was okay. In fact, it was fine. For the next three-and-a-half years, he rose before dawn every morning, made the deliveries and was free for other enterprises—an afternoon job in a candy factory, and night-time singing engagements that paid off in experience, if not in cash.

After a while, the experience paid, too. The singing jobs got better, until he was ready to form his own combo, “Bob Conrad and His Friends.” They did fine, played to crowds, he was making a living. But somehow he never seemed to pull the “right people,” the ones with influence in the entertainment world.

“Leave it to us, Son,” offered his mother Jackie and her husband Ed Hubbard. “We know the people who can help you. We’ll bring them over here to hear you.”

But he refused. The old ache was still with him. “I don’t want you shoving me down people’s throats,” he insisted. “I’ll do it on my own or bust trying. Just give me time!” His mother sighed and gave up. When she wanted so much to help, when it was only a matter of a little push here and a tactful word there—why did her son have to be so stubborn?

At home, it was an entirely different story. When he came home, Joan greeted him with open arms and his baby daughter gurgled ecstatically at her Daddy. He was the big man in their lives. And on March 1, 1954, he knelt by Joan’s hospital bed with his arms around her, admiring their new daughter Nancy.

Joan, tired but happy, “Wasn’t it a miracle, dearest, was born on your birthday?”

“She was exactly what I wanted,” he told her softly. “Show me a man who ever got a better birthday present.” This was a family man talking, with a wife and two babies depending on him. And he had just turned all of nineteen!

The hunger for success

More than ever, the hunger for success hounded him. And hard as the singing bug had bitten him, the acting bug now bit even harder. His dream was to study with Robert Schneiderman of Northwestern College’s drama school. But with the crazy hours he worked, how could he attend classes?

He went to see the famous coach, poured out his hopes and problems, and Mr. Schneiderman agreed to take him on privately. Meanwhile, he sang in clubs that were only so-so, all the while searching for a break that would get him into the better clubs, so he could take better care of his wife and children.

And then it happened! A swank new club opened in town and they wanted him. “We won’t pay you a salary,” they told him, “we’ll do better—a percentage of the net profits.” He hesitated, then decided to take a chance. In a place like this he’d surely be seen by the right people, the ones who could make his future.

At the end of two weeks, he came home to Joan with his share of the profits—a check for a hundred and thirteen dollars!

“I did better on the docks,” he told her.

“I won’t listen to such talk,” she said. “The docks weren’t getting you anywhere. This club might.”

But it didn’t! It folded right from under him.

He talked it over with Joan again.

“Maybe we ought to go to New York,” he said, and she didn’t bat an eyelash. If he wanted New York, they’d try it. Or maybe Hollywood, suggested by that young actor Bob had recently come to know, Nick Adams.

They tried New York first. When he made not the slightest dent, they took the rest of their savings, piled the babies into the car, and drove off for Hollywood. They hit the “golden city” mid-August, 1957. They found a little apartment to rent and phoned Nick Adams that they were in town.

Nick was still struggling himself, but he immediately took Bob to every casting director, producer, writer or anybody he knew. Bob nearly got a part, but the picture didn’t materialize. He got a small one in another, but neither the picture nor he proved earth-shattering. He pounded the pavements again, Hollywood style, making the rounds of offices and parties, both in hopes of being noticed. His savings dwindled, but the only words Joan uttered were of love and encouragement. Even while he went to the endless parties hoping somebody would “discover” him, and she sat home with the babies, she never complained.

Their last hope

In nine months there wasn’t a day’s work. They were down to two dollars that had to last a week until the next tiny unemployment check came in. And that day, the phone rang. He tumbled over himself to reach it. Maybe a part. . . .

It was his mother, “I’m opening my own public relations outfit, Bob, and I need you for a full partner.” Bless her, with her delicate tact. No “I-told-you-so’s.” No recriminations. She was offering a way out with dignity. All he had to do was bring his little brood home to Chicago and walk into a ready-made set-up.

He didn’t hesitate. “Mom, I love you for this, but I can’t.” It was her set-up, built by her brains and work. Nothing of his was in there. He had no right to the success it was sure to be. “I’ve got to make it on my own, Mother—in my own way.”

She pleaded. “Think of Joan, think of the children. At least discuss it with her.”

“Mom, I don’t have to. Joan believes in me. She wouldn’t want me to quit trying.”

They said goodbye and hung up. All that day, making the fruitless studio rounds, he told himself he’d done the only possible thing. A man doesn’t run away. When he was a kid, he ran away and let his mother bail him out. But never again! If he took the easy way now, no amount of money or prestige would keep him from being a nobody to himself. Not ever.

He went on knocking at doors that never opened. Finally, one opened a crack. A director casting for a picture gave him an appointment for an interview. He and Joan were full of hope. It was his biggest opportunity so far.

The day before the appointment a car, making an illegal left turn, smacked broadside into Bob’s car. He was thrown out with such violence that he landed in the emergency ward of a hospital, having his head stitched up.

“Do a good job and let me go home, will you, Doc?” he said.“I’ve got an important appointment tomorrow.”

“With this head?” the doctor asked indignantly. “Relax, buddy, you’re not going anyplace tomorrow.”

“It’s urgent,” he pleaded. “It’s—it’s a crack at a good job.”

The emergency doctor’s curt tone softened. “I’m sorry,” he said, “but you wouldn’t be able to work anyway—at least for a couple of weeks.” At the dejected silence he offered, “I’ll sign you out to go home, but I’m telling you for your own good, go to bed and let your wife take care of you.”

For a moment, hope flared in him. Once he got out of this hospital he’d use his own judgment. If he had to go after that job with a head bandaged like an Arab’s, he’d go! It wasn’t until he was helped off the table and onto his feet, when he discovered he was weak as a baby—that he knew. This was defeat again! Another chance—the biggest chance of all—knocked out from under him!

Home, he lay in bed and held tight to Joan’s hand, because this time his courage had hit a low that was almost lower than he could take. Eyes shut against the pain in his head and his heart, he prayed silently, not to distress Joan with his misery.

And then it happened

“Dear God,” he prayed, “am I ever going to get my chance? I try, I do what’s right by my lights—am I doomed to stay a nobody the rest of my life?” But he didn’t ask God to help him get a part after his head healed. Jobs you find for yourself—prayer is to take comfort from talking with God. That was the way he saw it.

And that was the way it happened, finally. For no more reason than the bad breaks had hounded him, the good ones sought him out. He got some work in “Sea Hunt,” it led to more TV work, and finally to the best break of all—his part in “Hawaiian Eye.”

One day he said to his wife, “I guess I don’t have to tell you how good it feels to be a somebody at last.”

“Why you big lug,” she said fondly, “in my book you were always a somebody.”

“Me? When I drove a milk wagon? When I was nothing but a hunk of muscle loading on the docks?”

“Honey,” she said, “you were a great guy to your wife and kids even when you came home every day smelling like a gooey candy factory. Even when you sang for coffee-and-cake money, I knew you’d get someplace because you had what it takes.”

“You mean like luck?” he asked with a grin.

“I mean like guts—which you have.”

“I have you, that’s what,” he said, and kissed her. “For a fellow bucking his way up, that’s the most to have—a wife like you.”

Joan reached up to return the kiss.

THE END

BE SURE TO SEE BOB ON ABC-TV, WEDNESDAYS FROM 9-10:00 P.M. EDT, IN “HAWAIIAN EYE.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1960

AUDIO BOOK