Sandra Dee: “I’m In A State Of Shock!”

Sandra the bubbly, Sandy the joyous imp, Sandy whose laughter can be so infectious it lights up a whole set and forces everyone within earshot to join in—this Sandra Dee is no more. Today, she is sobered by life, her child face motionless as a mask, her eyes two dark holes. As she talks, tears hover on the edge of her eyes and on the edge of her little voice. Today, she is the saddest girl I’ve ever seen.

“I’m just in the dark,” she sighed. “I don’t know what’s going to happen. I’ve learned so much in these last months. I’ve learned you can love a man and still have trouble with him . . . more so than if you didn’t love him because then it wouldn’t matter at all . . .”

Slowly, she fingers the wedding ring she still wears and looks out into space. “It’s not easy for Bobby either, you know. He’s in the dark, too. Oh, I want so to be happy. I don’t know what it’s going to take, but that’s what I want . . . happiness. Right now, I’m happy most of the day. I’m working long hours day after day, on ‘Take Her She’s Mine.’ In between scenes, we play a game called ‘Essence.’ I play with Kay (Kay Reed, her hair stylist), I play with Mark (Mark Reedall, her make-up man) . Everyone joins in the game and that keeps you busy. And it’s a cute picture, and a hectic one, fast-paced, funny. I’ve had to learn the guitar, learn to accompany myself for the three folk songs I sing—Bobby’s racket. But I have to go home at the end of the day. I’m not happy the minute I’m quiet. I’d like to have quiet happiness again.”

This wistfully . . . she’s had no quiet happiness since Bobby left, to make night club appearances from which he never returned. It was one month later before Sandra announced their separation.

Still in shock

“We’d been separated for a whole month before that announcement. I was in shock. I couldn’t make any announcement. I’m still sort of in shock. A little disillusioned with life, this isn’t by choice. . . . You know the only boy I’ve ever cared for is Bobby. I never really dated until Bobby. All the teenage layouts in magazines were publicity stuff. According to the press reports, I was the biggest run-around that ever hit this town—and I never had a date. Weird, isn’t it?”

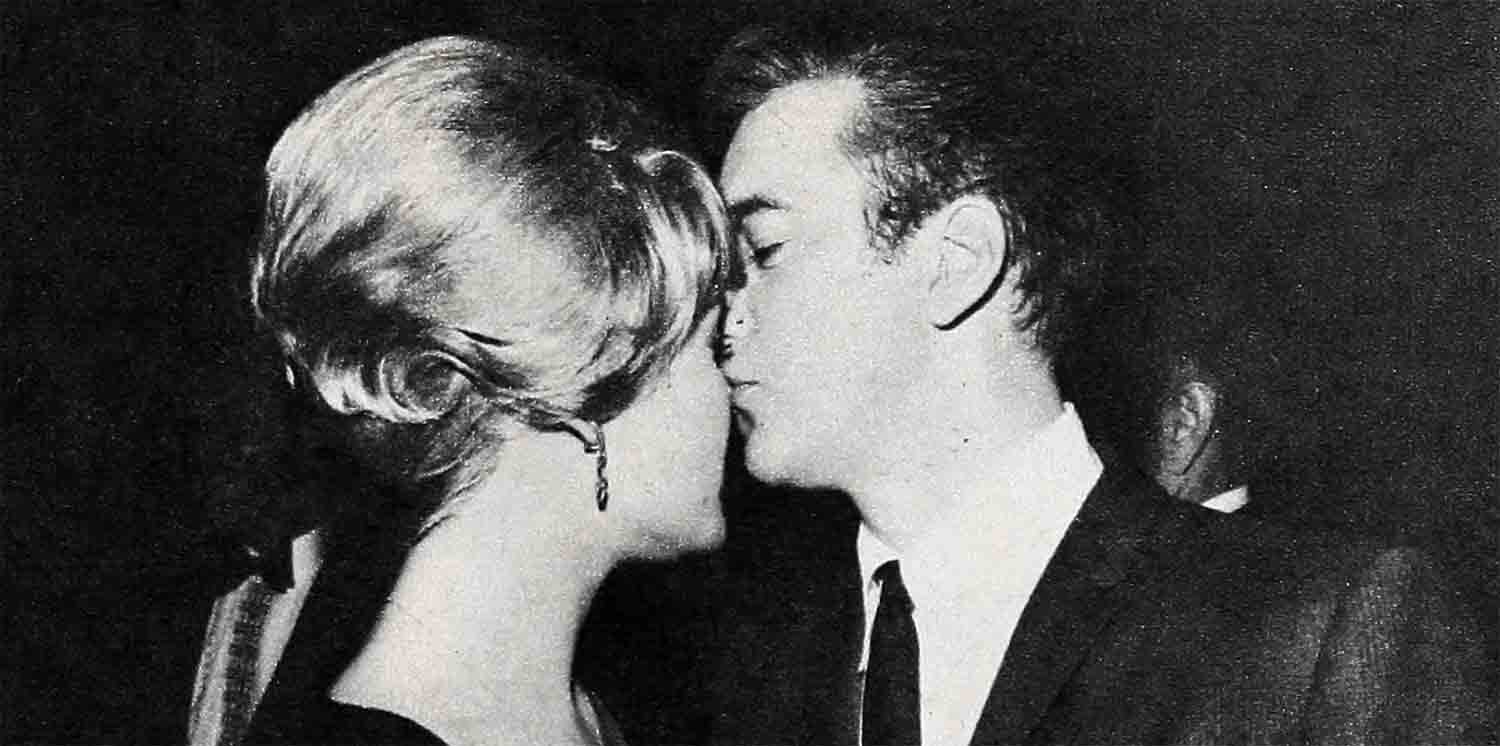

The old Sandy would have grinned and made a pixie face. Today’s Sandy articulates the words as if she doesn’t know what they mean. “Bobby was my first real date. He gave me my first real kiss off screen. It’s fantastic. He wouldn’t believe it at first—about being my first date. He did after that kiss. And I’d hated him so at first, when we first started shooting ‘Come September.’ But when you react so violently to a person there has to be a reason. It was strange to discover that it was love.

“It’s hard for someone who went from nothing to marriage. I’d had no life but work, really, and I’ve never been able to adjust to Bobby’s life. I can’t. I’m naturally slow-paced and he’s a whirlwind. A brilliant man, everything he does . . . he devises most of his own material. He can make pictures, appear in night clubs, travel all over, do everything a mile a minute. I can’t. You should see me now crawling home at the end of the day. I’m so tired I can scarcely bend over to pick up Dodd.

“This little boy, he’s something else again.” For a moment I thought she was going to smile. She didn’t. She just reached and picked up a cigarette. “He’s wonderful. Sixteen months old, he talks—‘I want,’ ‘Mamma,’ ‘Daddy,’ ‘door,’ that sort of thing. Of course no one understands him except Bobby, the nurse and me. We had a myna bird we were keeping for a friend and the baby started mimicking him.”

She can’t stop talking about the baby—her one link with Bobby. “Dodd’s a good little boy and very funny. I saw him the other day sitting in the projection room with a cigarette. Just like Bobby, only it wasn’t lit and he had the wrong end in his mouth, I didn’t want to tell him.

“He used to look exactly like Bobby, but he’s changing. He has Bobby’s eyes and my nose and mouth, my color hair, blond, very thick and curly. I wish I could give you a picture of him for the magazine but that’s something my husband has always been adamant about. No pictures of the baby. I never agreed with Bobby on that and I don’t really know why he felt that way, but it’s something I can’t break away from just yet. I’m not sure, even though I used to argue with my husband about it. I’m not sure yet.

“Bobby loves this little kid the same as I do. He’s crazy about him, and the baby’s crazy about Bobby. He loves men, I think all babies do, because men have a different attitude. They don’t jump at each thing like a woman does, they don’t keep wiping his face and smoothing his hair. If he gets dirty, so he gets dirty. He loves to watch Bobby shave. As a matter of fact, Dodd just came back from the Flamingo where he stayed with his daddy from Tuesday to Friday.”

The baby has traveled from the time he was born. For a while it looked as if he’d be born in Texas where Sandy was on location with Bobby for “State Fair,” but they made it home in time. Three weeks after Dodd was born, he took his first excursion—to Las Vegas. Since then, he’s been to New York, Buffalo, Chicago, Boston and back to New York and back to Las Vegas, time after time. This was a little family that was always going to be together. Nothing was going to separate them. Not for a minute. Even when Dodd began to walk and it wasn’t so easy to keep him quiet on a plane or in a hotel room. But now Sandy is working at Fox, Bobby is playing Las Vegas, the baby goes visiting, and Sandy has eyes like two great dark holes in her face.

Once in New York, she was all alone with Dodd and he had a temperature of 105°, a virus, the New York doctor said. Bobby had gone to Boston for the night, the nurse had a virus downstairs, Kay, Sandy’s hairdresser, had a virus upstairs and there was Sandy alone with eleven-month-old Dodd and he was burning up. She panicked. She phoned her Aunt Ollie in Jersey—she and her aunt have always been very close, Sandy’s always been crazy about Ollie’s boy Serge, and now Aunt Ollie has a baby girl and she left both with colds to come help Sandy.

“Smarter than I am . . .”

Three days and three nights of this fever in a room with a little oven to heat the place so the baby’d perspire . . . but then it was over and he has never been ill since. He’s a husky fellow, weighs twenty-seven pounds, is thirty-seven inches tall and has always been a great eater until lately, when suddenly he’s lost interest in his food and is wild for the dog’s food.

“He’s too much,” Sandy says. “He’s going to be smarter than I am by the time he’s three. I never knew a child could be such fun. He won’t use a fork to pick up his meat. No, sir. Not ever. He’ll pick up the meat and put it on the fork. He throws his food on the floor and yet he’s so neat in other ways. He sees things, picks them up, puts them in the ashtrays . . . goes around stamping butts out. I’ve gotten a great charge taking care of him. It seems too bad now, to leave home so early he’s still asleep and not see him all day. But I want to work like mad right now. Work, work, work. It keeps your mind on something constructive. I leave home at five in the morning, get home at six thirty, and that’s all. It’s a godsend the work. At first I thought, how could I ever make this picture? But here I am.”

Sandra Dee. The Cinderella girl. I stayed at the studio for her birthday party late that afternoon. They’d been shooting the sequence where Sandy, in a bikini, is painting in front of the house. Late in the afternoon, a cake was wheeled in, bouquets of flowers and photographers swarmed onto the set. “Happy birthday, Sandy. What does it mean to be twenty-one?” someone yelled.

“It means after nine years of work, almost three years of marriage and a sixteen-month-old son, I can finally vote, order a glass of wine in a restaurant and show my navel.” She was alluding not only to the bikini but to several other abbreviated costumes for the picture including the magnificent Cleopatra dress made of twenty-four-carat gold cloth, the top a sort of half bra.

“What’s your next picture, Sandra?” called someone else.

“ ‘The Richest Girl in the World’—and I will be, literally. Ross Hunter is letting me keep all the Jean Louis clothes and it’s killing me.”

She’s very flip. She poses for pictures, puts on a good show for the cameras. But later, back in her dressing room, she has a headache, takes a couple of aspirins and admits she’s feeling a little sorry for herself. “It’s weird,” she says. “I’m happy and unhappy. Disappointed a little.” She keeps scanning the nine great bouquets of flowers. One has a tag with no name. Maybe the flowers are from him, maybe not. She phones home. The baby is fine, the nurse is fine. Bessie Binger. “She’s one of the things I’m happy about. I’m closer to her than to anyone right now. Closer even than to my mother. My mother I can’t involve in this business about Bobby and me. As a matter of fact, this is something I have to do alone.”

And it’s the first time she’s had to do anything alone. In her childhood, there was her father, then her devoted mother, Mary Douvan, then Ross Hunter, who discovered her and has become her closest friend, then Bobby. Through the years there’s always been someone looking out for Sandra.

I remember our first meeting. It was at MGM. the day after her fifteenth birthday. There’d been a party on the set and “Baby” wore her hair in pigtails. “Baby.” Everyone called her “Baby.” Director Bob Weiss had given her a bicycle to ride around the lot and her mother had given her a little champagne-colored fur stole. She told me then how hard it was to wait. she felt half kid and half grown up and she’d never had a date and if a boy even talked to her she felt flustered and fussed.

She could hardly wait to be sixteen . . . drive a car . . . go out without her mother . . . get rid of the teacher-welfare worker to whom she’d been glued from the moment she arrived in Hollywood. She was frantic to be married. And twelve months later was telling me, “So I’m almost seventeen and I do drive my T-bird and love it. But now that I don’t have to go anywhere with my mother, I go everywhere with my mother. Now that I’m about to graduate. I’m brokenhearted at parting with Gladys Hoene, the teacher who taught me to like teachers. Romance is still ahead. Dating is still ahead. I still dream of getting married but the fact is that having arrived in Hollywood—sophisticated, but the most—I now feel like a kid just beginning to grow up.”

“I didn’t know how lucky I was”

I remind today’s Sandy of this and she remembers very well. “I didn’t know how lucky I was, having the teacher and working such short hours,” she sighs. “I couldn’t work more than eight hours and three of those were school and one lunch. Isn’t it funny how the appeal is lost, once no becomes yes. The best cigarette I ever smoked was in the bathroom with the window open. It’s never been as much fun since.”

“So now you’re twenty-one.”

“Yes, and I’m not very happy. I’m happy with life and yet a little disappointed, a little disillusioned, I’ve never been that way before. I’ve changed. This is the first time I’ve been conscious of change. Here I am. I’ve had so many hopes and they have mostly come true. Now some of my hopes are being broken. I suddenly realize I’m a mother, I have a great kid, I also have a personal problem—and for the first time in my life. I’m facing it alone. This is the first time I haven’t had anyone to lean on. I’ve been carrying the ball.”

It hasn’t been easy. For several weeks, Sandy stayed at home, took care of the baby and said nothing. She took the baby, went to Palm Springs, came back. Then she took him, and the nurse and Kay Reed and Universal-International publicist Betty Mitchell and went to Hawaii. It was hot and lovely and Sandy and the baby spent all their time on the beach. Then she came home and made a statement that she and Bobby had separated.

“And then I lived through two weeks of hell. It began the next morning with news-reel photographers on the front lawn. Dodd couldn’t even go out to play! I hadn’t expected anything like this. I hadn’t really made any announcement. There has been no talk of divorce. This is really just a pause in which we decide what to do. I didn’t expect it to hit the front pages. In London, it was on the front page!

“But I’m learning. I guess what I’ve learned primarily is patience. I was number one on the list of wanting everything to happen yesterday. I’ll probably never be patient again if I survive this. And I guess I’ll survive. You hear of friends going through unhappiness like this and you think, ‘My God, I’d die.’ Well, you don’t die. You’d like to but you don’t. You are tougher than you think. You just live very quietly one day and another. That’s what I’m doing. There’s no incentive to go out at night. I used to go out because it pleased my husband. Now to please myself, I go to bed. Period.”

“And nothing is black. You keep thinking this is the worst thing in the world until something else happens that makes the first catastrophe light by comparison. I thought things were at their worst when my grandfather died some months ago.

“But I’m beginning to understand. No matter how much you love someone. . . . And Bobby’s the best husband, so protective. He acted all the time as if he were afraid I’d break.”

I remember when they went to Dallas for “State Fair.” They went to Neiman Marcus to shop, and crowds mobbed them. Sandy was about to have the baby any minute and Bobby was terrified. He got the manager to keep the store open one night just for them and they bought all the baby things.

“Bobby is able to do anything, move mountains. And isn’t it strange the reason I disliked him so in the beginning was that he was so forward and I was so backward. And after a while I loved that. Domineering is just how he is, he can’t help it and I like it. Being married to a man who’s so positive has its advantages. I never wanted to wear the pants. I never wanted to make decisions. I haven’t. Bobby’s made them. And he never pushed me too far. He knew when to push. With the baby he’s very definite. Careerwise Bobby’s definite, too, of course.

“And you know what my father once told me. ‘Never push life, just let it happen’—well, that’s how I’m living today. I can’t remember what I did yesterday. It doesn’t matter what I did. There’s nothing to do but wait and hope for happiness. I want to be happy. Someday that means having someone with me, being close to someone, having more children. Right now it just means patience.

“And Hollywood has nothing to do with it. If you make a success of anything, you have more demands on you, you have more money, you just naturally change. I don’t say I haven’t changed since I was fifteen, I say if I had stayed in modeling I’d have changed. Everyone changes. When you are a success you have more enemies and more friends, more of everything. I have few friends my age because I didn’t go to school and there are so few people my age with whom to have anything in common. They’re either married and absorbed in that or not married and scattered all over.”

Someone brought in some coffee and Sandra drank hers. She hadn’t touched the birthday cake. She couldn’t.

I thought of the fifteen-year-old “Baby” surrounded by loving care and it occurred to me how lonely this girl must be now. Ross Hunter for years has stood by as mentor. He lives right next door to the Darins. He never knew one thing about Sandy and Bobby until he read it in the paper. Sandy was at a party at his house on Thursday, Ross left the next day for London, the following day he read the story in the paper.

“It’s as it must be,” Sandy says. “I’ve been carrying the ball alone. I have to. There’s no one to lean on. Any relative or friend of mine couldn’t be unbiased and this has to be unbiased. This is a different situation. There’s too much at stake. There are three lives. . . .”

She couldn’t say any more. Tears were too close. Twenty-one years old—she has everything and nothing . . . and you don’t die, you can’t die, you just wait.

—JANE ARDMORE

Sandy’s in U-I’s “Tammy and the Doctor,” and 20th’s “Take Her, She’s Mine.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1963