When A Star Finds Heaven

The man in the bathing trunks, the aqua-lung and the goggles, with the snorkel breathing tube in his mouth, was so excited he shivered, even in the tropical waters off Nassau.

He had never tried skin-diving before and—like everything else he undertook for the first time—he considered it the greatest.

The water was so clear, the sand at sea bottom so white, the marine grottos so lovely and the fish so exotic that the skin-diver was impelled to comment on it all. What he said was, “What a sensation—what beauty—what mystery. . . To the few curious fish about, it sounded like nothing. Then Kirk Douglas lost his snorkel tube, took on a load of limpid sea water and had to be hauled to the surface.

Afterward he confessed sheepishly, “I was so at home in the water that I forgot I didn’t have gills.”

His embarrassment was unnecessary because the incident was a capsule story of his life: normally he plunges into an alien situation, is delighted by it, identifies himself with it and, having merged with the medium, he comes up triumphant and refreshed.

Zestful is the word for Kirk. He has a dynamism that belonged to the strapping, hard-muscled heroes of long ago: men like Beowulf of the north and Ulysses of the south, whose life, incidentally, Kirk recently helped to put on film.

During the past two years, Kirk has covered around 50,000 miles. In rolling up this mileage Kirk has worked and/or vacationed in Israel, France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Nassau and Jamaica. Usually he has known where he was, but he had an uncomfortable moment in Rome. He was having dinner at the Excelsior Hotel one night when he heard a musical cry fall from the public address system, as follows, “Kee-airk Doo-glah, telefona; Kee-airk Dooglah, telefona.” Idly, he mused that an able song writer could do more with it than could be done with some such sound effect as “Sh-Boom,” but dropped the matter there.

Somewhat later a friend joined Kirk at table, and asked why Kirk had failed to answer the page. Kirk said nobody had paged him. “In Italy,” said the friend, “when you hear ‘Kee-airk Dooglah,’ get with it. That’s you.”

Not only did he fail to recognize his name over the loud-speaker, there were times when he was stranger to the character whom he observed in the bathroom mirror getting his teeth brushed each morning. The interloper was wearing a curly red-gold beard which was the pride of a local barber.

The barber had taken charge of Kirk’s facial hedge when it was as fine and few as a mouse’s eyelashes. As the weeks went by, the skilled scissors snipped a bit here, a bit there, shaping, coaxing, sculpturing. “I began to feel like a French poodle.” Throughout the picture’s shooting schedule, Kirk had to return—every few days—to the barber to keep his facial costume in satisfactory Ulysses trim.

Probably the happiest American east of Rothschild’s Beverly Hills haircuttery was Kirk the day he was told that the picture was finished, there would be no retakes, and he could find out if he still had a face under the feathers.

Dropping into the barber chair with a joyous grin he said, “Off it comes.”

The barber took one step backward in an eloquent Latin gesture of shock and managed to shake his head. “No,” he said, brandishing a pair of razor-sharp scissors. “You keep. So beautiful. So thick, So curly.” His hands shaped a beard in the air. “Boys have faces like girls. Men have beards.”

The discussion continued with Kirk begging for a shave and the barber begging for the life of his masterpiece. “Let’s put it this way,” Kirk said finally. “If you won’t shave me, I’m going to someone who will.”

That was the haymaker. The barber asked for a picture of Kirk wearing the beard, then set to work to destroy what he considered an obvious work of art.

The original Ulysses loaded his ship with odds and ends of merchandise picked up from the shores he touched, including now and then a slave maiden. His Douglas counterpart did okay with the exception of the slave maiden; in that case he secured a stunningly better break. We’ll get back to that later.

Not one to collect tangibles ordinarily, “I’m not a personal possessions guy,” Kirk broke a rule by having several pairs of alligator shoes handcrafted for him by Cucci of Rome. He bought slacks on the island of Capri, sport shirts in Venice and ash trays made of Arabic bracelets in Israel. These additions to airplane luggage presented no particular problem, but Herr Douglas fixed himself up just fine in Munich.

In one of the mesmerizing top shops he spied an electric train that did everything except sing “On the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe.”

Kirk once told an interviewer, “No man is completely a man who has lost out of himself all of the boy.”

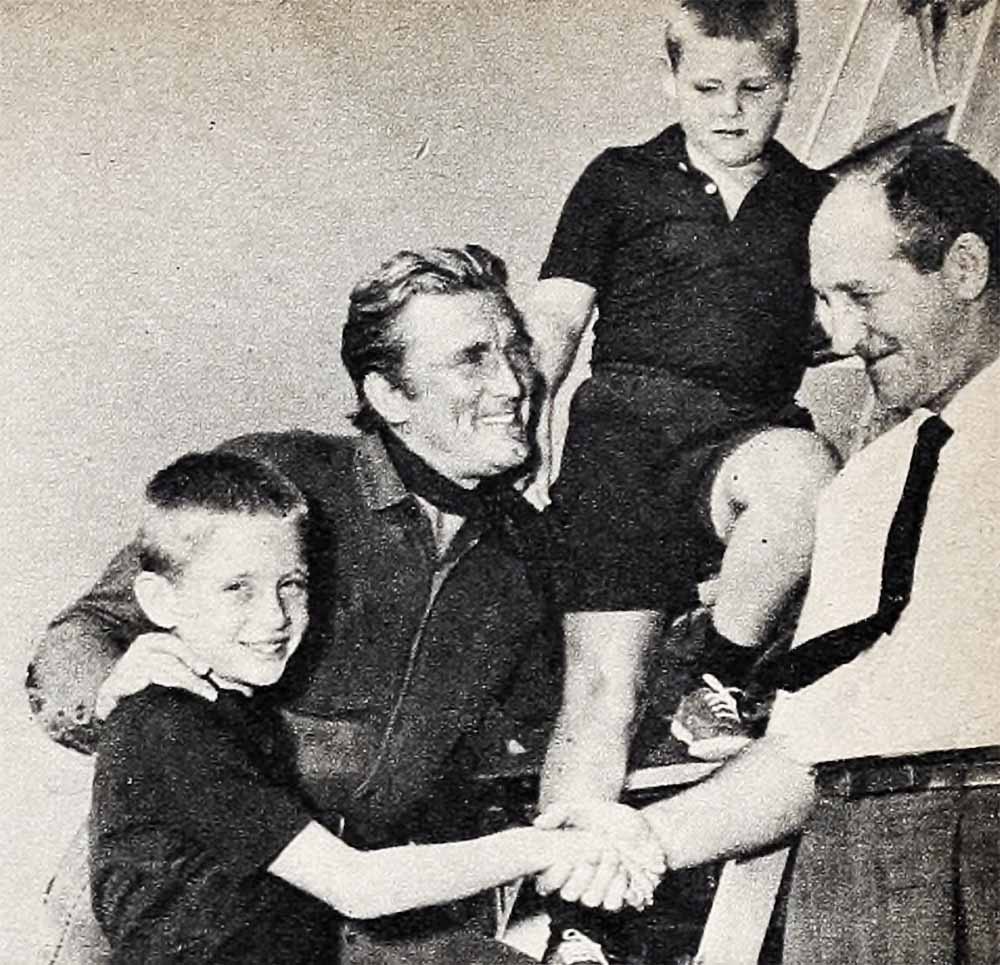

What happened next proves that Kirk is completely a man without having lost the small boy touch. He bought two trains. Because,” he explained quickly, “I have two sons. Can’t come home without a present for both.”

Also, the trains were impressive bargains. The exchange was to Kirk’s advantage and he was spared the import duty which adds heavily to the cost of imported toys when purchased in the U.S. However, the trains were so heavy that before he had finished paying the overweight airplane baggage charges as he lugged the presents over the face of Europe, he could have bought a diesel unit for the Super Chief with the outlay—“Darned near, anyhow.”

Of course, the intangibles that a man brings back from two years in faraway places are the things he keeps forever. Kirk has a dream sack full of them.

He reached Venice late one afternoon and was shown to his room in the Gritti Palace Hotel. Strolling to the casement windows, he was overwhelmed by the sight of sunset turning the Grand Canal golden.

Everyone carries away a bit of Rome. The portion that stuck in Kirk’s memory is the cobblestone Piazza di Spagna from which ascend the Spanish Steps. On the corner still stands the little house in which John Keats died in 1821, at the age of twenty-six.

On that corner Kirk would meet Anne and they would set out to explore the fabulous city. Together they found another treasure: an Italian love song, “Com’ E Bella.” Kirk would like to record it some day, with a French ballad, “Tu Ne Peux Pas Te Figurer,” (You Can’t Imagine) on the flip. (Incidentally, have you picked up a copy of Kirk’s Decca pressing of “Whale of a Tale,” backed by “The Moon Grew Brighter?” Good listening.)

What man who has been to Paris has failed to take away with him something of “the city that is loved as a woman is loved?” Not Kirk. He started modestly then scored a grand slam. He loved Paris; everything was great—with one exception . . . He was having a certain amount of trouble with his guidebook French.

Like the night he sped out of his hotel, pressed for time, and told the cabby, “Paramount Theatre, s’il vous plait.”

“Comment?”

“Paramount. PARAMOUNT. . .”

“Comment cela?”

Kirk sprinted back into the hotel, summoned a bellboy and explained his destination. Said the bellboy to the cabby, “Pah-Rah-Moont Theatre. Pah-Rah-Mont!”

Dawn burst over Eiffel Tower. The cabby’s eyes expanded, his eyebrows leapt upward, and he shrugged as only the Parisian can shrug. “Ah—mais oui—Pah-Rah-Moont.”

Kirk settled himself in the furthest corner of the back seat and revised, with some frustration, the remnants of his college course in German—his only attempt until that moment to master a foreign language. Phrases bubbled to the surface of recollection, things like “Ich liebe Dich,” “Du bist ein schones Madchen” and other airy persiflage. ‘I’ll never use it,” Herr Douglas told himself glumly.

The only certain thing in life is its uncertainty.

She came on the set for “Act of Love” one day. She was wearing a bright red coat —unusual for the black-loving Parisienne—and Kirk wanted to know who she was. He was told that her name was Anne Buydens (pronounced approximately Bwedaw), that she had been born in Germany. She spoke four languages fluently; French, German, Italian and English.

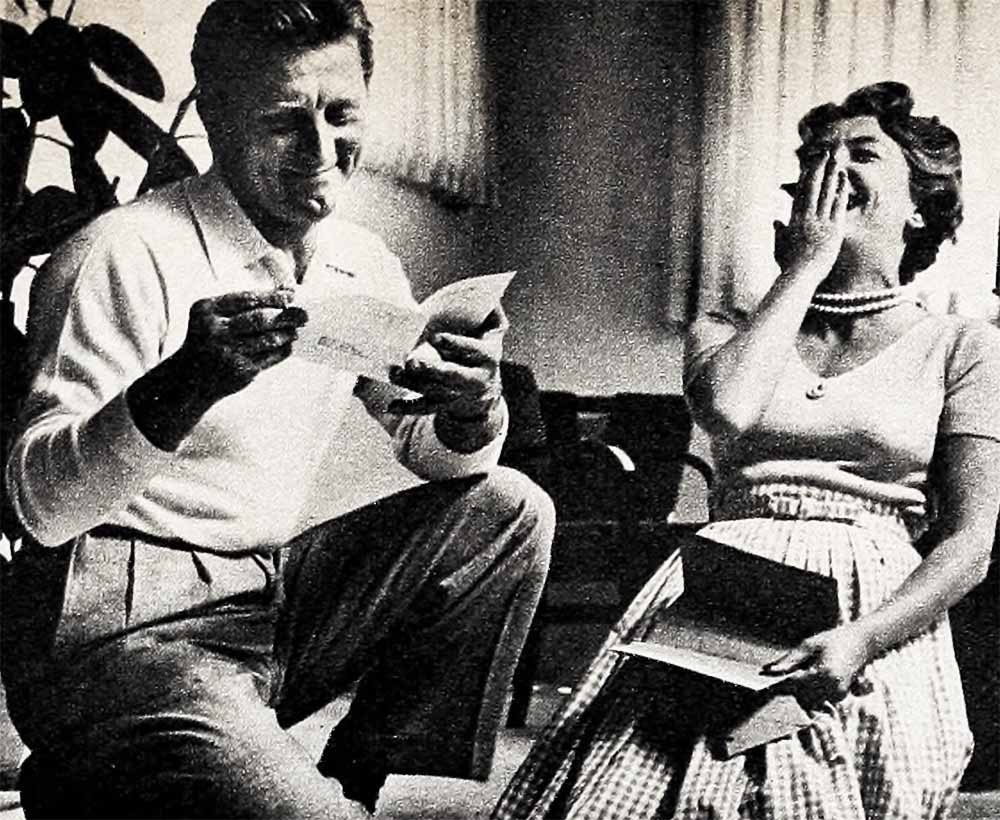

Madame Buydens and Kirk finally met through their mutual friend, Anatole Litvak, who knew Kirk was in need of someone to steer him through French and allied hazards and to serve as press-relations expert.

Kirk explained to Madame Buydens that she had been mentioned glowingly by several persons, Tola Litvak among them, and that it would be deliverance if someone 114 who knew her way around both the motion-picture industry and the continent of Europe would come to his aid.

Madame Buydens said thank you very much, but she had never done that type of work, so she could not consider herself the proper person to undertake the assignment.

Could he take her to dinner that evening and discuss the problem? Kirk ventured.

Madame Buydens thanked Mr. Douglas pleasantly, but she had a dinner engagement.

Well, then, could he drive her home and discuss it on the way?

That was thoughtful, but she drove her own car.

Kirk gallantly escorted her to same. At the time he was driving a Simca, which is—roughly equal to a Ford. Anne Buydens was driving a Porsche, a German car equivalent—roughly—to a Buick.

Trumped again.

The ancient Ulysses lashed himself to the mast in order to avoid bodily injury while listening to the siren’s song. His modern counterpart exhibited no such concern for life and limb. When, in the course of conversations overheard at parties attended by both Anne and Kirk, he learned that she was going to Klosters, Switzerland, for the skiing, he rushed to the resort in advance.

Outfitting himself from cap to boots in what the upright skier should wear, he took a few lessons so as to remain that way. When, a few days later, Anne’s train pulled into the Klosters station, there stood the American skier, Kirk Douglas, ready for the snow job of his career.

Quicker than you could say “slalom,” a romance developed, and the first thing Kirk knew, he was wandering through gift shops, collecting sweaters, purses and gloves in Anne’s favorite shade of blue.

Back in Paris, she cooked small dinners in her apartment for Kirk. By that time Kirk had begun to take a knowing interest in oils; he fell in love with a Brayer which hung above the apartment fireplace. It recorded a peasant festival, and it was a delight to the color-loving eye. Long afterward Anne was to say, “I shall never be entirely sure whether Kirk married me for myself or in order to become half owner of the Brayer.”

When Kirk had to visit Brussels, he asked Anne to guide him, since she had lived there. She convoyed Kirk through a series of art galleries and restaurants, two of which proved to be memorable. Kirk spotted an oil by Utrillo—the study of a church and a crowded Street under brilliant sunlight—which he coveted. (Not being clairvoyant, he had no idea that this canvas would one day be his wedding gift from Anne.)

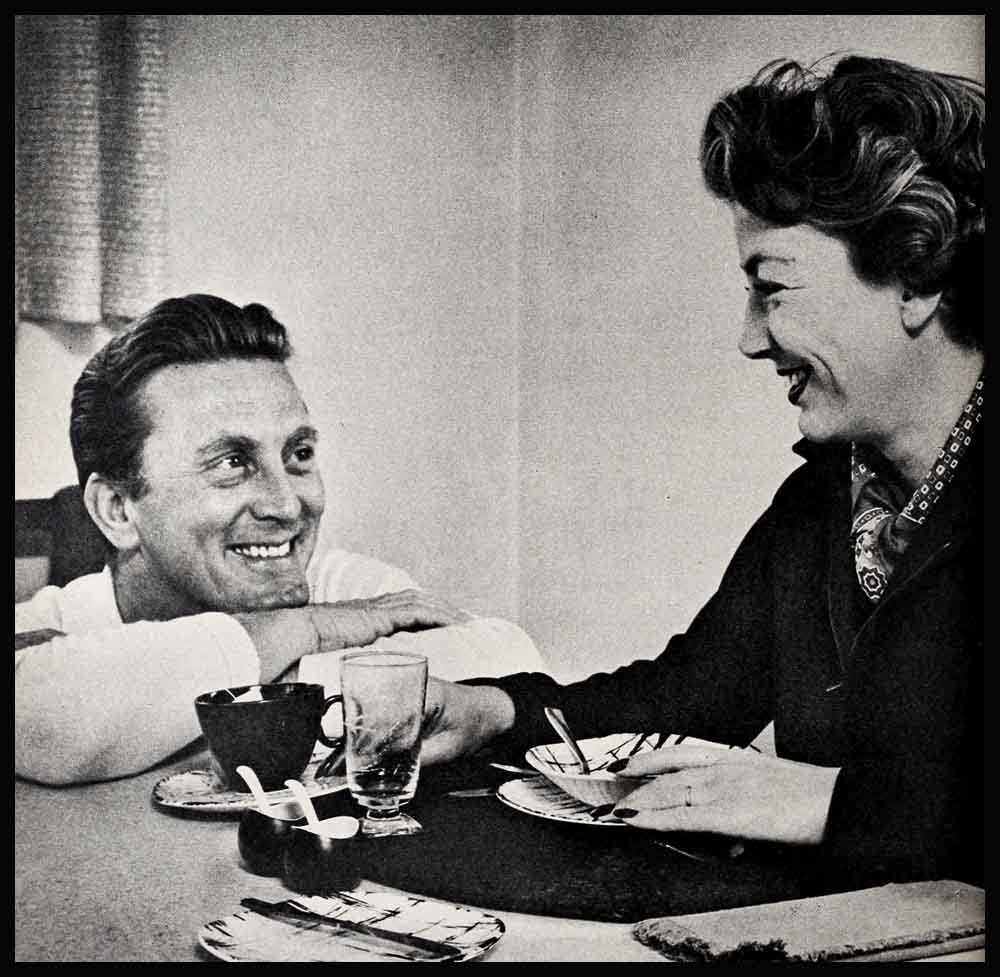

The restaurant was Le Filet de Boeuf, situated on the square (La Grande Place) where it had once been a fine home like others along the Street. Its exterior trim was gilt so that in the red sunlight of late afternoon Le Filet and its phalanx of neighbors looked like a picture torn from a child’s storybook. The restaurant’s dining room contained only six tables, but there the simplicity ended. The linen, the crystal, the heavy antique silver, as well as the china, were treasures, and the dinner proved to be merely the best Kirk had enjoyed in Europe. Kirk told Anne so as she sat opposite him, smiling in the soft candlelight.

Not long after, he traded candlelight in Belgium for sunlight in Jamaica, and set to work in “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.”

He was entranced by the island, by the Round Hill Hotel, by Calypso, by the explosive shirts, by the frenzied native dances. He could have done without the native driving, but even that supplied a small pivot on which great events turned.

Driving to location one morning, a jet process through villages which jumped backward—both man and beast—to make way for the careening car, the driver was unable to avoid a fine fat pig. After a shrug for the departed pedestrian, the driver would have charged on if Kirk hadn’t intervened. “We’ll have to find out who owned the pig and pay for it,” he insisted.

The driver thrust out his head and yelled, “Hey, pig-owner! Pig-owner! Pig-owner!”

No response. After a few more calls the driver flung out his hand in a gesture of dismissal. “Boss, this pig ain’t got no owner,” he announced and drove on.

Kirk thought about it with a wry grin. There in the road lay a fugitive wanderer, having lived his brief, careless life and having ended in the dust without an owner to claim him—or to collect his insurance.

Even, mused Kirk, the great Ulysses had finally come home after twenty years. Perhaps he wished he had done so earlier. In any case there came a time when one had to admit to various ownerships. Possibly that was one of the great lessons of travel.

So Anne Buydens was invited to California to see whether she liked the country, the people, Kirk’s two sons, Mike and Joel, and Mr. Douglas. A three-ply affirmative vote took her to Las Vegas on May 29, 1954, to become Mrs. Kirk Douglas and are planning a new addition to the elan.

In other respects Kirk is sinking roots. Kirk has now gone into business for himself, having established Bryna Productions and made releasing arrangements through United Artists. The first picture will be “The Indian Fighter.”

After two years and fifty thousand miles a man must have absorbed a conviction or two: Kirk admits to one major conclusion. “The more you see, the more you realize, humbly and gratefully, how wonderful it is to have been born in the New World, in the Americas, where opportunity is as real and sustaining as the air we breathe. I’ve never forgotten that I’m the kid who sold newspapers, collected bottles for pocket money, waited table, drove trucks, earned my way through college, got a picture break and wound up in Hollywood. Some of that flashed through my mind as I stood in line at the Command Performance reception, wearing white tie and tails, and awaiting my turn to be presented to Her Royal Highness, Queen Elizabeth II.”

The Queen murmured a friendly phrase to Kirk, something like, “How nice it is to have you visit us,” and afterward reporters besieged Kirk to find out what, exactly, had been the royal words.

Kirk was not going to give up to the I printed page the moment he, himself, could not quite believe. “What Her Highness said is a secret between the two of us,” he murmured with quiet dignity.

Wonderful world, huh?

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1955