He’ll Never Win An Oscar

It is a curious and yet undeniable fact that in forty-odd years of show business—the last twenty-four of them in Hollywood—Archibald Alexander Leach has rarely been tabbed “An Actor.” Not in the sense that indicates lofty critical praise. He has been acknowledged to have, and he has, great physical magnetism. It is generally conceded that he is handsome. But in the last definition of the craftsmanship he has sought and in which he has been so long successful, he has been little honored.

It may be said now that this circumstance has not escaped the attention of Mr. Leach— who in 1932 decided he would be more euphoniously known as Cary Grant. Indeed, it has irked him, since Cary Grant’s notion of screen acting is vastly different from that of the press or public.

So, for that matter, is Cary Grant’s notion of everyday behavior. But it is only recently that Mr. Grant has got around to unburdening himself on these and a few other subjects. Apparently, up to now, no one remembered to ask him.

AUDIO BOOK

One day in the late winter of this year, Grant sat himself down behind a pot of tea—since a vicious attack of hepatitic jaundice, he no longer drinks or smokes—and answered anyway. He was a little harassed by time and pressure. In a few days he would leave for Spain and the making of “The Pride and the Passion” for Stanley Kramer. Frank Sinatra and Italy’s Sophia Loren would also be among those present, but Grant’s was the bedrock name. He’d been setting in order a house in Palm Springs and a house in Beverly Hills. But he behaved like a man who had not a single urgent engagement until 1960. He is a singularly courteous, uninhibited fellow.

Mention inevitably was made of the then upcoming Oscar awards, and he smiled whitely beneath his somewhat graying hair and above his rather full chin. “I won’t win it,” he said equably. “Not that I’m nominated, of course. But when I say I won’t win it, I mean now or any other year. I don’t say I should, and I have nothing but respect for the nominees. But ‘acting’ by today’s critical lights has something to do with facial acrobatics and missing teeth. Light comedy has no more chance than the man who keeps his features still. You know, any amateur can black out a tooth, stick on a beard, and pretend he’s something he isn’t. The tough thing, the final thing, is to be yourself. That takes doing, and I should know. I used to be Noel Coward. Hand plunged in the jacket pocket, you know. It took me three years to get that hand out of there, and they were three years wasted. Noel Coward is great at being Noel Coward, but the role I do best is Cary Grant.

“In fact,” says Mr. Grant, “the same general idea goes for everyone under every circumstance. But it’s so hard for people, especially the young, to find it out. You see a girl enter a party or any kind of crowded room. In a moment, she goes into a role. Her hand touches her hair. She does something meaningless with her arms. Her natural poise has deserted her so she’s superimposed another poise. If she’d simply stick to being herself, she’d be a hundred times more charming. But that’s something she’ll have to learn. I doubt that it can be taught.”

Grant, oblivious to the double-takes of fellow-diners who by then realized they’d flushed a screen star, poured more tea and re-routed himself to the original subject of Oscars, cutting across a few hilly digressions to head them off at the pass.

“So I’ll never get one,” he said. “I had a crack once. Instead of a droll fellow in a dinner jacket, I was a psychopathic murderer. Picture called “Suspicion.” But when it was over, my poor victim got the statue. Joan Fontaine. That’s when I folded my tent and stole away.

“Really, though—and this isn’t sour grapes—actors know the problems of acting and no one else does. Not fully anyway. Well, how could they? A fan letter from Ethel Barrymore would be worth more to a player’s self-esteem than a thousand good notices. The truth is, not many critics know what they’re talking about. That’s an observation, not an indictment. They’ve been kind enough to me. But they just don’t know. It’s what I’ve been talking about. Let a player roll his eyes and chew scenery and the critics get excited. They dig up that one about ‘submerging himself in the role,’ and I guess by inference curl their lip at Cary Grants. So all right. But they still don’t know what they’re talking about. The stage—that’s something else. But on film, the actor who Controls his face and plays himself—he’s the one who’s learned his business.”

On reconsideration, the reference to the stage suddenly agitated Mr. Grant’s bile. He’s done the stage bit himself, and presumably knew whereof he spoke.

“Now there’s something,” he said. “Broadway’s assumption of superiority to Hollywood. There is something. And the gifted young men—and they are gifted, more times than not—come here from there and promptly fail apart on the simplest take. Because they know nothing of the making of pictures. Where they had a whole stage to work on and could cover for a multitude of errors, here the smallest mistake screens as a cataclysm. And I can’t tell you how many mistakes you can make in one close-up scene. I can’t even show you because it would take too long.”

But there was time for seventeen technical errors, which he demonstrated in rapid succession. “I’m before a camera now. It’s a close shot, necktie up. You’re—oh, Grace Kelly. I say to you: ‘I’m here today, gone tomorrow.’ That’s all. And take a sip of water somewhere in between.” He spoke the line and went through the business. At the end of each take, he said: “But I can’t do it like that. Setting down the glass, I drowned out a word. And I can’t do it this way. Did you see why? I’ve a double-chin and forgot to hold it up. This time I’m holding the glass so an arc-light’s reflected in it. Broadway wouldn’t know about these things.”

Did Grant, then, as an established star, have doubts about those who were Corning up so fast behind him, the Rocks and the Tabs, the Rorys and Tonys?

“No!” he said. “In fact, I’m glad you asked me that. I’m with them all, and I know what they’re going through because I went through it once. I was talking about technical deficiencies. No, these kids have it and they’re going to deliver it. Their problem is one of concentration, utter concentration. There’s so much, when you’re on the way up, to distract you. So many trimmings and trappings. And all necessary. Makeup, publicity, photographer, that first self-consciousness at being a more or less public figure—oh, everything in the world. including the fear you might not stay on the streetcar. I’ll come to that. But in spite of it all, their big job is to concentrate, learn their business, and forget the rest while that’s going on.

“See, if you can’t do that, you’ve really got a problem. I mentioned Grace Kelly.

Of course, we’ve lost her now. But concentration! That girl could study a script with a house burning down around her. And when she’d finished, she’d know every nuance and every thought the character had to have. That’s only one of the things that made her great. Bergman had it, too. The big ones all have it. I know someone once asked Spence Tracy what the first important thing was a young actor should do to get a foothold in this business. I imagine they expected one of those faith-and-courage answers. But Spence just looked up for a second and said, ‘Well, it might be a good idea if he’d learn his lines.’ He wasn’t kidding a bit, either. I’m not running down faith and courage, but learning your lines is at least just as practical.”

And what about the streetcar bit?

“The streetcar bit,” said Grant. “It’s my visual apparatus for the Hollywood scramble. The streetcar fills up in the back and empties out the front. And there’s only room for so many. It’s a precarious sort of streetcar. Call it Aspire. Call it anything. When I first jumped on the back and was hanging on the rail for dear life, the ones up front in the aisle seats were people like Richard Barthelmess. You know? Well, I hung on like mad and shoved and pushed and finally had a little room with the standees on the rear platform, and I thought, well, so far, so good. Then I looked behind me and there was another crowd trying to get on. And a few of them do and that shoves you up a little further toward the front. Gary Cooper got on about the same time, I think, only a little earlier, but he’s the one nobody’s shoving. Coop sits there with his legs stretched out and lets people trip over him.

“Then all of a sudden you hear a shout, and someone yells back to us in the rear, ‘Hey, So-and-So’s fallen out the front!’ And that’s the last you hear of So-and-So. That streetcar represents Hollywood to me, and where I am now I won’t guess.”

About three-quarters forward with a snug seat at the window?

“That’s a comforting way to look at it.”

Yes. But there is also the possibility that the point does not really concern Grant to any great extent. At a youthful fifty-two and in his full streetcar status, Cary Grant is thought by his friends today to be bearing away on a course parallel to stardom rather than toward it. That is, his career has come to have more significance to him as a means than an end.

“I don’t think,” an intimate observed of him recently, “that Cary wants to work his head off any more. Say three pictures every two years, and the rest of the time traveling or just taking it easy and boning up on the civilization he lives in. His horizons have broadened—and God knows, he isn’t hungry any more.”

Nor are these the only changes evident in the man. The younger Cary Grant was a fellow with a considerable range of mood, from a kind of euphoric gaiety to numbing, surly depressions. These last were particularly apparent after the breakup of his marriage to Barbara Hutton Reventlow, which had a tragic quality of its own. Of all the unions this unhappy woman has essayed, that with Grant seemed to have had the best footing. From her, Cary Grant neither wanted nor needed a single thing; this made him distinctive in the ranks. No one doubts that he loved her, and most think this love was tinged with a measure of tenderness that could be called pity. Assuredly he wanted to see the marriage work. Just as certainly, he exerted a heroic effort toward that end.

But he failed. Or someone failed. Or something. Miss Hutton was said not to be terribly fond of Cary’s friends, for example; and not exactly overwhelmed by Hollywood, when she saw it against her haut monde playgrounds in Europe.

Cary and Barbara were married on July 8, 1942, in a ceremony at Lake Arrowhead, and Grant at that time was a gregarious, earthy sort of chap who liked Cockney dialect, sang ribald songs to his own piano accompaniment, and talked incessantly—as on occasion he still does. “You’ll find me a fertile subject,” he told an interviewer recently. “I gabble on like a New York cab driver.”

But when the two were divorced a little more than four years later, Grant went into periods of dark silence, and strange phases of passing friends without recognition. His habitual expression became a glower, and friends guessed he had reached a point of view that could be summed up in the words: Success is a phony and attainment absolutely pointless. Well, it is possibly not a very healthy way to feel.

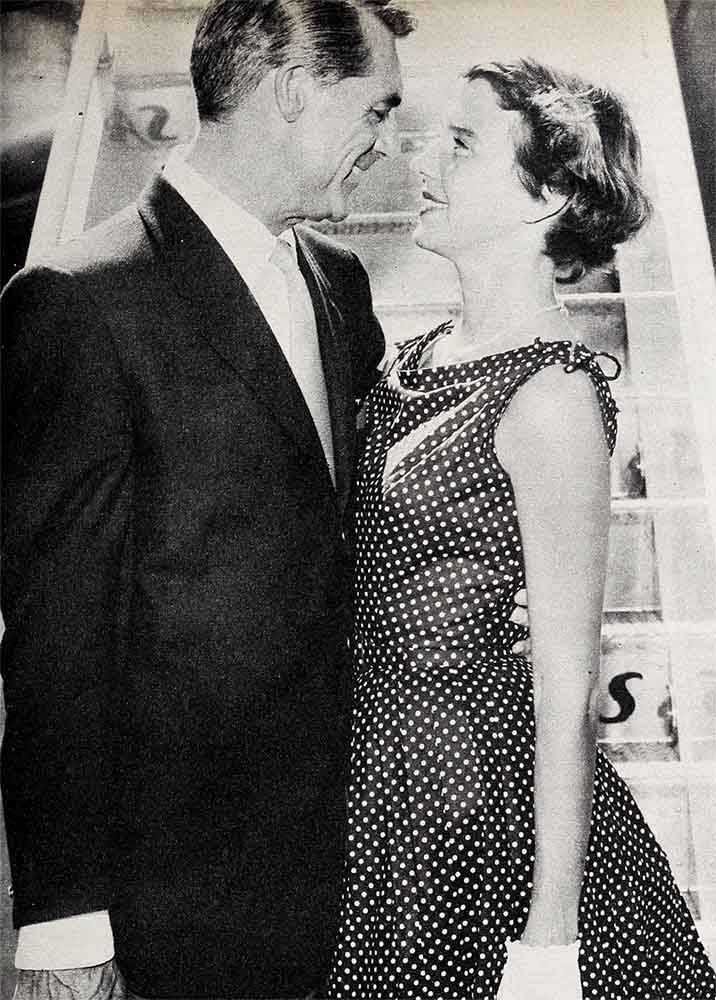

But, as history well knows by now, along came a young actress named Betsy Drake, and to him she was the redemption of everything, most conspicuously love and hope. They met in 1948 and were married as soon as humanly feasible. She is Cary’s third wife—his first was Virginia Cherrill, a 1934 union that lasted two years—and by any reasonable betting odds his last one.

“I love her so much,” Grant said a few weeks ago, “that for once, words fail me.”

Now the moods and depressions are gone, the gaiety less hectic. With maturity (and Betsy) has come an amiable mellowness, together with an inclination to stay home and investigate in more detail what goes on between the covers of books. Home is high in the section of Beverly Hills that really is given over to hills, the suburban extension of a flatland of box hedges and well-manicured lawns. Here the Grants live quietly, staying away from television a good deal of the time, while Betsy reads or putters and Cary continues his scholarly pursuit of what the hypnotists are up to; a subject, by the way, that interested him long before Morey Bernstein took out after Bridey Murphy.

There was a time, according to associates, when Grant drove too conspicuous cars at too many miles per hour. Now he drives modest, middle-priced cars at a sedate pace, staying over in the right-hand lane and rarely moving to pass the slowest deterrent to his progress.

“Cary,” a friend has said, “even if he was late to a party, wouldn’t pull out to get around Don Wilson pulling Jackie Gleason in a rickshaw.”

Our newly tranquil Mr. Grant was born in Bristol, England, on January 18, 1904, the son of a clothing manufacturer and grandson of a British actor of some repute. Cary himself thought at an early age he’d like to follow Grandpa’s steps, but he likewise thought he’d like to be an electrician. Presently, while he was still not much more than a child, a chance to bracket the two arose. He conceived a new theatrical lighting effect and took it to the manager of Bristol’s Princess Theatre, who was delighted. He even installed it.

And thus a bridge was crossed. The lighting device was the last Grant was ever to create, but the theatre became his love forever. At thirteen, he broke out of the home corral to join the troupe of one Bob Pender, a group that specialized in eccentric dancing, stilt walking, clown routines and pantomime. Cary had been with it four weeks when Leach pere dropped around and dragged him home by the scruff of the neck.

Eighteen months later, however, our hero escaped again, rejoined Pender, and got his father’s blessing.

No w Grant was a knockout comic—strange apprenticeship for the economy of style and motion he later was to evolve—and the company played the Hippodrome in New York. The year was 1920—and nothing happened. But back in England, something did. Grant, singing now, was noticed by producer Arthur Hammerstein, who brought him back to the States for “Golden Dawn.”

Grant remained on Broadway for a succession of musicals: “Polly,” with Fred Allen and Lady Inverclyde; “Boom Boom,” with Jeanette MacDonald; “Street Singer,” with Queenie Smith; and “Nikki,” with Fay Wray and Douglass Montgomery.

“I got by in New York,” he has lately recalled, “but it’s hard to say just why. Because I had black hair and white teeth, I guess. Looking back now, I can’t account for it any other way. But I found out one thing: The stage actor who yells that he can’t be bothered with Hollywood—that guy already has his bags packed. And the louder he yells, the bigger his hope chest.”

Grant, who has admitted from the first he had his bags packed, motored to California after “Nikki” closed, and by and by was playing straight to a promising actress for a Paramount screen test. And as happens now and then, the lady turned out to be not so promising, but the stooge caught a few influential eyes.

They became ayes as well, which leaves us with very little more to say that is not a matter of record.

Grant, who became an American Citizen on June 26, 1942, and meanwhile took time to legalize his more famous name, enjoyed a success that for its unbroken nature has proved somewhat monotonous. Not to him, though.

He also enjoys tennis, badminton and swimming, roughly in the order named, but professes no hobby in particular. Still, there is ample time for him to find one. Outdoor dinner parties featuring barbecued critic, for instance, might prove just the thing.

THE END

LOOK FOR: Cary Grant in United Artiste’ “The Pride and the Passion.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1957

AUDIO BOOK