My Girl, Debbie Reynolds

The letter that arrived yesterday morning worried us. My youngest brother in El Paso, Texas, just eighteen and in his first year of a four-year college scholarship, announced his plan to marry immediately if he could get my consent. When Debbie came home from the studio and heard the news about her young Uncle, she cracked up a storm and began spluttering.

“The dope! Marry at eighteen! Holy cow! With three years of college ahead of him? He’s only a baby. Why—why, I’ll buy him a ticket to Paris—anything. Only we must try to talk some sense into him,” Debbie begged her grandmother, who is visiting us.

AUDIO BOOK

Debbie’s fuss ended, however, when Grandmother pointed out that she had no right to interfere—any more than she would if Debbie made such a decision. If Debbie wanted to write her Uncle her views—all right, but it wasn’t up to the family to influence him one way or the other.

Debbie’s like a lot of teen-agers I know. She’s been brought up to use her mind to make her own decisions. And thank goodness. For how else does one prepare a daughter to take the good steps, the right steps toward adulthood and marriage?

Debbie’s ideas against early marriage are strictly her own. Her own brother Bill married at nineteen. I married at sixteen—and very happily—so I’ve never tried to influence the children one way or the other. Dad and have tried to show Debbie what constitutes a good marriage indirectly, and listening to her views at present, I think we’ve succeeded.

Once, when Debbie was a little girl in El Paso, she watched me setting four places at the table for dinner. It was even before the birds and bees period of explanation! Debbie appeared to be thinking deeply, looked up at me and said, “When I get big, I’m going to ask ten children to come live with me—not just two. What do I have to learn to have my own house?” I told her she could practice taking care of children with her own dolls, that she’d learn more and more each year and by the time she was ready to marry, I hoped she’d know the answer.

Today, I think Debbie knows how to run a home of her own, even though, because of the demands of her career, she has had less time to practice household arts than other girls of her age. Yet, I feel confident she’ll make out all right.

What mother ever thinks she’s done a perfect job on her children? None. And that’s as it should be. What I’ve done for Bill and Debbie is try to make them self-reliant and to respect not only others but themselves, too. Debbie’s grandfather used to tell her, “Live by the Ten Commandments and you’ll be all right.”

Debbie was born in El Paso on April Fool’s Day, 1932, Dad was a railroad carpenter on the Southern Pacific in that town. When she was eight, Dad was transferred to Los Angeles and we found a house in Burbank. We’re still there, and Dad is still on the job. Our home is about twenty miles from Debbie’s studio, M-G-M, but it’s thousands of miles away as far as the glamour and razzle-dazzle of Hollywood is concerned.

None of us would have it any other way. Our home was, and is, run for the family as a whole. We share pleasures together and we share responsibilities together. When Debbie was very young, I gave her duties, such as setting the table, helping with the dishwashing, making her own bed and picking up her clothes in her room. On the last, though, I’ve never had much success. And when I talk to the mothers of Debbie’s friends, I find they haven’t had any greater success. Debbie frankly doesn’t like household chores, and I can’t say I blame her. Neither do I. But confronted with the necessity, such as when I’m visiting my family in Texas, Debbie can do a pretty creditable job with our Burbank home.

Our neighbors, watching my daughter play sandlot baseball, dressed in old faded blue jeans and T-shirt, shake their heads and say that she lives and acts little like their conception of a movie star. Recently Debbie completed a theatrical engagement in “Gigi” in St. Louis. We were at the airport and Debbie bought an armload of movie fan magazines. Two women nearby kept eyeing her.

“It sure looks like that Debbie Reynolds,” one whispered to the other.

“Nope. It couldn’t be.”

“Well, how do you know.”

“Simple. No movie star would be reading movie magazines.”

But if they’re listening, it was, too, Debbie, and she does, too, read fan magazines. She’s as big a movie fan as any. “Only way that I can keep up with my friends, now that I’m so busy,” she says.

And now that I think of it, it’s a good thing those St. Louis doubters didn’t see Debbie, her dad and me sleeping all night in our car the time we drove our son back to his Army camp and couldn’t find any place to stay. They’d never have believed she was in films, for sure.

True, after five years of picture-making, Debbie’s got a swimming pool (though we had to give up our whole back yard for it and Debbie had to make two theatrical tours for the money); a crystal mink stole (her past Christmas present to her- self, purchased as a bargain because it was made up for someone else and turned out too small); a new white and shrimp-pink Mercury (bought at the factory and driven home last month). I suppose that proves she’s .a movie star, but she also sells Girl Scout cookies and that proves her sense of values hasn’t changed.

Debbie and I have been all wrapped up in scouting ever since she was old enough to join (we still are counselors), and she has more different badges of merit than Mr. Carter has pills—including one for baking and cooking! Frankly, I think they were looking the other way when they handed her that last one! But seriously, it’s my feeling that if you get a boy or girl interested in some such character-building community organization, you need never worry that he or she will take the wrong path in life. And that’s why I never lost sleep, lying wide-eyed in bed, waiting for Debbie to come home when she first started dating.

I must say though that I almost despaired of her ever taking boys seriously. She was interested in them, all right, but only so far as their prowess in football, baseball and bowling was concerned. Debbie loves sports—all kinds. In fact, if you pasted up a list of her favorite sports on a giraffe, the ones she considers “real cool” would extend from top to bottom. (I’ve just remembered I mustn’t say “real cool” any more. As soon as I learn to use one of Debbie’s bebop expressions, she says that one is as outdated as the dodo and I’m a “real square” if I still use it.)

Debbie’s brother Bill treated her as a kid when she tagged along to play baseball or football. Like most big brothers—he’s two years older than she—he’d say, “Gosh, I wish I could trade that kid sister of mine for something useful, like a bike.”

Bill would tease her, saying, “Greg thinks you’re peachy-keen.”

“Really?” Debbie would glow. “How did he like my one-handed catch yesterday? Smooth, huh?”

“Naw, I mean he’s got a crush on you.”

“Oh, fiddlesticks,” she’d explode. “Boys!”

But around sixteen or so, she began to discover that boys are here to stay. And her interest in clothes mounted in the same ratio. I’ve made most of her clothes because Debbie has always been tiny for her age. Now she wears a size seven and can find dresses in that size, but formerly it was impossible. Anyway, she couldn’t afford all the store-bought clothes she needed—and wanted. So whatever free time I have from housekeeping, my work with the Red Cross, Girl Scouts and Blood Bank activities, I’m glued to the sewing machine.

The result? Dresses, coats, suits, formals, overflow her room-length closets. And Debbie, unfortunately, is the kind of girl who must try on five outfits before she’s ever satisfied. The other night, Bob Neal, a young Texan, was over. Hoping I’d embarrass her, I asked him if he’d like to see the result of a baby Texas cyclone and took him into Deb’s room. But he wasn’t unhappy. He merely picked up a box of snapshots of Debbie and looked at them.

Debbie’s grandmother shook her head. “Sake’s alive, Maxene,” she said, “how do you ever expect to get that young one married off if you let her fellers see how untidy she is?”

Frankly, I’ve done nothing to try to get Debbie married. That’s up to her completely—just as her career is. She’s been dating Bob Neal, Tab Hunter, Hugh O’Brian, Bill Shirley and a young plastic surgeon, Dr. Michael Flynn, besides lots of boys not in pictures. But I don’t think our Five Foot Dynamo is really in love yet. When she is, I’ll know it. Because Debbie is a shouter. She’s been called “the lass with a delicate air”—but not by me.

Since she was eighteen Debbie has been making five-dollar bets with friends at the studio that she wouldn’t be married at twenty-one, twenty-two, or twenty-three. One with Lana Turner, I think, is now due, and Lana owes Debbie five dollars. Debbie has all the little signed slips carefully hidden away, and if she doesn’t marry this year or next, she stands to collect about one hundred dollars.

I know that lots of girls look over every date with a calculating eye while hearing those distant strains of Lohengrin. Not Debbie. With her, it’s just fun, whether it’s a date for bowling, dancing, beach picnic, barbecue party, a premiere, a movie. When it comes to clowning, that Vitamin Kid can outclown any three girls. But neither her dad nor I worry about Debbie winding up an old maid. When the time comes, the right man will find our daughter. For years she’s been saying she wants to marry a doctor because they’re such wonderful men. She’s even told our family doctor, but he just laughs and says, “Heaven help him. It’ll set the profession back ten years!”

Debbie’s standards have always been high. She’s really embarrassed in a lowcut glamour gown. Photographers are always saying, “Take your hands down, Debbie.” This innate modesty colors everything about her. She doesn’t drink or smoke, and she isn’t going to be talked into it by the people around her. She says she’ll never marry a divorced man —won’t even date a man until his divorce is final. “Say,” I heard her shrill over the phone the other night, “is your year up yet?” (She was referring to the California law which demands a year waiting period before a divorce is final.) Nor will she date a boy a second time when she finds on the way home that, as she puts it, he “develops as many arms as an octopus.” When she dates, she picks her escorts carefully and she wants to know where she’s going beforehand. “It doesn’t have to be a big production,” she explained to me, “but we have to have some activity planned. I like the accent on action, so there isn’t time for parking in the car or looking for dark corners.” Wolves-about-town she refuses to date.

Because I think Debbie is mature enough for her age and because so many other young actresses have their own apartments, I once asked her if she’d like one—nearer to the studio. And she exploded: “That’s like saying our home isn’t good enough for me. I love it here and I want to stay until I marry. I’d hate to live alone.” So, quick-like, I dropped the suggestion. Dad converted the double garage into a little guest house, thinking Debbie would like it for study and rest when we didn’t have house guests. But Debbie won’t budge from the house.

The truth is that Debbie is as contented in her home as a five-year-old in a candy store. She’s been all over our country and to South America, to Korea, Japan, Mexico and she’s been a guest in the most glamorous estates around town, yet she’s never felt the slightest bit ashamed of our modest home. I think this is because we’ve never taught her that the biggest is the best. And if she should marry a young man just starting out in a profession, she’d be content with their circumstances. Though Debbie’s eyes are green, she’s never envied friends who have more of the world’s material possessions. When young people are jealous and envious of others, I think it’s because parents have neglected to instill a pride of home in their children—a pride based on the comforting fact that of all the houses in the world one alone is home.

In this, Debbie’s attitude is mature, just as it is in her work. At first, I admit, that little character I call my daughter looked upon acting as a lark. Then she began to grow and to take it seriously. The change was noticeable. She’s gone from child to grownup. For it’s my belief that the ability to stick to a job—to struggle through it until it’s finished—is a real test of maturity.

Like honey, she sticks to anything until she becomes a part of it. Take the French horn, for instance. Personally, I’d rather not take it—but Debbie practiced and practiced until she could play it well while she was in high school. Lately, she’s been persistent in learning to dance, sing, do ballet, gain proficiency in diction and dramatics. She’s shown endurance, accepted unpleasantness, discomfort, frustration, hardships. And she’s learned to size things up, make her own decisions.

Once when a friend asked my husband, Ray, some question about M-G-M, Ray said he’d never been there. And he hasn’t. And I’ve been there only when necessary.

I remember that the studio school teacher suggested that I come and supervise Debbie daily. I declined, politely. (I have a life of my own, too.) And when Debbie was eighteen and through school, the teacher said that now, more than ever, a young girl should have her mother with her at the studio. “Debbie.” I told her, “is self-reliant and has-sound judgment. I’ve every confidence in her. She isn’t going to do anything that she wouldn’t do if I were here watching her.” And she didn’t.

Debbie handles all her own affairs—decided on the details of her new contract, selected a business manager who allows her twenty dollars a week for spending money. She uses it for lunches, movies, banana splits and malteds, bowling, buying herself a belt or a scarf and many weeks she’s amazed to find a few dollars left over. This ability to budget is another sign of increasing maturity.

But when Debbie first signed her contract with Warners when she was just sixteen, I confess Ray and I weren’t quite ready to let her make her own decision about a career. No one in our family had ever had theatrical ambitions and we weren’t sold on the idea that there’s no business like show business. We were a bit skeptical about the whole idea. (Only recently my mother found out that Maxine Elliott, the great stage star, was a distant kin of ours. Frankly, I have to confess that I’d never heard of her or that a theatre was named for her on Broadway.) Actually, we would much rather have seen her go on with her ambition—to become a gym teacher. Without telling Debbie, we went to the studio and had a long talk with everyone she would be working with. And we concluded that Debbie would be in a safe environment—that these were all mighty fine people.

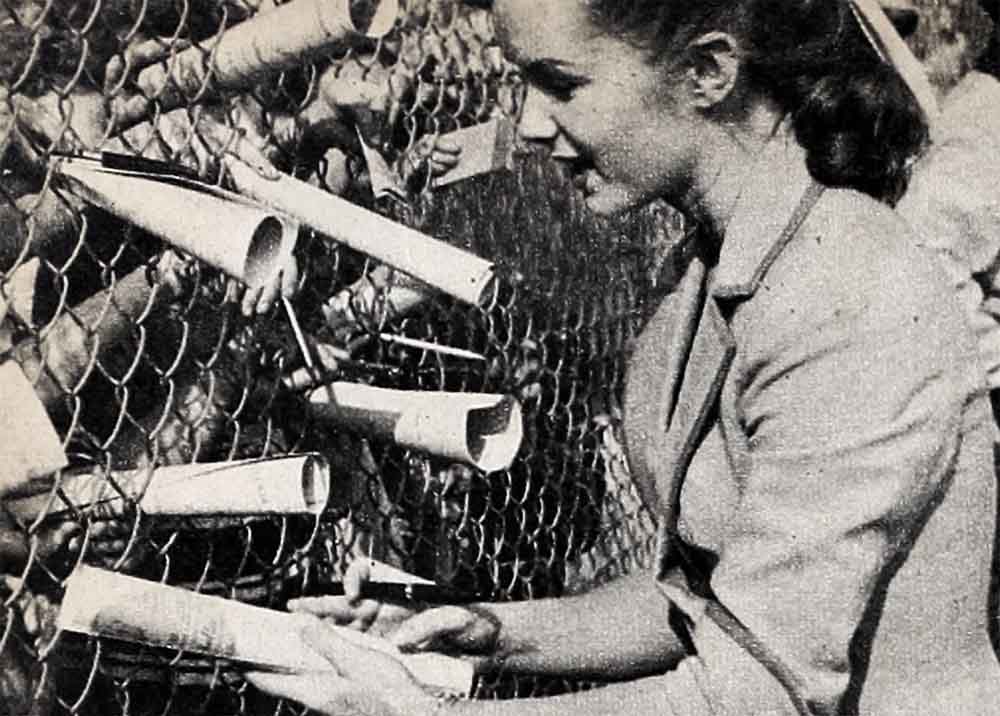

Sometimes I suppose Debbie must think longingly of her ambition to become a gym teacher. She has so little leisure time now. Tourete, her poodle, and Henry, her cat, scarcely see her these days. And her collection of toy monkeys gathers dust. “Heavens to Betsy,” she laughs, “if I had a husband it would be ‘Hi’ and ‘Bye’ and I’d have to give him a picture of me to remember me by.” She blows in exhausted from a long day at the studio, and even if she has a few days off to go to Palm Springs, the time is pretty well filled with picture layouts and personal appearances. Every chance she gets, she’s off entertaining at camps and hospitals. This is her personal contribution and she’s never too tired or busy to continue with it.

Dad likes to watch wrestlers on TV—Debbie considers them like yesterday’s corn fritters, so after dinner, if she doesn’t have a date, she gratefully climbs into her bed, chews away vociferously on a stick of gum while she grows a crop of goose pimples listening to her mad passion—murder mysteries on the radio. Right now she’s in the throes of reorganizing her possessions which, like a Scotch magpie, she’s hoarded through the years—old school jumping ropes, athletic equipment, cheerleader batons, dolls, magazines, scrapbooks, letters and pictures. She covers her bed with sorted piles, then puts everything on the floor when she goes to sleep. Next night, back everything goes on her bed, while she continues the sorting.

Dad and I look in on this bundle of energy and wonder what we’ll do for laughs when the day finally comes that Debbie leaves the house as a bride. We both never hoped to be perfect parents to Debbie. Nor have we demanded perfection in her. We’ve been aware of the necessity of give and take on the part of all of us, and that’s why, I think, we have always had a happy home. And without pinning a blue ribbon on myself, I think Debbie—together with many of her girl friends—will make a fine potential crop of mothers and I envy the girl who’ll be my grandchild.

Anyway, I think I pay her the highest compliment when I say I’d be happy to be her daughter!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1954

AUDIO BOOK