What Psychiatrists Are Saying About The Liz Taylor Syndrome?

(Background Information on the special problems confronting beautiful women in the public limelight has been supplied by a number of psychologists, psychiatrists and psychotherapists. Most helpful in this respect has been Nancy L. Bloomberg, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist certified by the State of New York. The specific application of this information to the problems plaguing Elizabeth Taylor, however, has been made by the present writer, and all analyses and interpretations of the “Elizabeth Taylor Syndrome” are his own, based on a careful examination of voluminous files of printed matter and on confidential reports.)

What is it about Elizabeth Taylor that when she sneezes or buys some dresses or visits a night club it immediately makes news ’round the world?

What is it about Elizabeth Taylor that makes men—even the meek ones—smile when her name is merely mentioned?

What is it about Elizabeth Taylor that intrigues women?

What is it about Elizabeth Taylor that has made her a hospital patient in almost every year of her adult life . . . that has exposed her to appendicitis, influenza, incipient ulcers, severe colds, ruptured spinal discs, throat nodules, meningism, tachycardia, staphylococcus pneumonia and, most recently in Rome, a throat hemorrhage or a nervous disorder or food poisoning or acute fatigue, depending upon what edition of what newspaper you happen to read?

What is it about Elizabeth Taylor that seems to attract trouble, invite scandal?

What is it about Elizabeth Taylor that has caused her to have four marriages (two of them ending in divorce), although she is just thirty years old?

What is it about Elizabeth Taylor that has made her one of the most infamous and famous women in the world?

To answer these questions it isn’t enough to quote Lord Byron’s phrase, “the fatal gift of beauty,” and let it go at that. The answer won’t come, either, by examining each of her illnesses as an isolated example of physical malfunctioning, or by putting her marriages under a microscope and dissecting each one separately; or even by looking into any one scandalous episode in which she has been involved (or allegedly involved).

What will give you the answer is the over-all pattern of her life and her behavior. To discover this we must go back to the beginning of her trouble, or as near to the beginning as authentic reports and records permit.

The roots of her trouble stem from her family situation when she was a child. The general story is well known by now, yet often very crucial details are omitted or glossed over in the telling.

Liz’ mother is a frustrated actress. As Sara Sothern, she was just getting somewhere in her stage career, when she married the handsome, wealthy, “quiet” Francis Taylor. The word “quiet” is the key one here. Mr. Taylor took a back seat to the mother. Mother is the aggressive one; father is quiet and lets mother lead.

When Elizabeth is born and grows into a pretty child, her mother’s own desires to be an actress are transferred to her daughter. And because there’s safety in numbers, because if one fails the other may succeed, she has the same ambition for her son Howard, two years her daughter’s senior. He is as handsome as her daughter is beautiful. He must be an actor, too.

So when the daughter is nine, the mother arranges for her to begin her screen career. At the Taylor dinner table there is nothing but talk of Elizabeth’s talent, Elizabeth’s beauty, Elizabeth’s imminent stardom. That is, the mother talks, and sometimes the daughter contributes a word or two, while the father and son sit silently, picking at their food. All Mrs. Taylor’s energies, hopes and desires are devoted to making her child a success. Nothing else matters.

Then, for six months the child literally has no father. The mother and father separate. Is it that he can’t stand his wife’s need to dominate? In any case, they drift back together again, but the father represents no major source of strength for the little girl.

Imagine the absurdity of this child’s life. Her mother is always with her, and her father is . . . her father is . . . the movie studio. She is overprotected, overdriven, overstimulated. She produces emotions on cue before the camera; she is alternately pampered and pushed. She is a child without a childhood. She wants to rebel, but she doesn’t know how to rebel. She is a puppet, with no inner life of her own. Her body doesn’t belong to her; her face doesn’t belong to her; her mind doesn’t belong to her.

She puts the problem succinctly herself: “In school, at the studio, we weren’t even allowed to stop to daydream in class. So I used to escape to the girl’s room.”

Bored . . . bored . . . bored . . .

The one word that crops up most frequently in Elizabeth Taylor’s description of her feelings about herself and the world—then and now—is “bored.” This is what psychologists and psychiatrists call a screen word, a convenient mask to cover a variety of painful emotions: fear, insecurity, inferiority. “Bored” when youngsters her own age ignored her; “bored” when no one asked her for a date when she was fourteen—and, again, when she was fifteen.

Then, according to the files on Elizabeth Taylor, she discovered a secret, not consciously, but she discovered it nevertheless. She found out that people would pay attention to her when she was sick or hurt. She was always bumping into things on the set, falling over her own feet, even getting a sliver of steel in her eye. And when these things happened, people noticed her. The directors, producers, fellow-actors and her mother would panic and act as if the world were coming to an end. But most important, her father would pay attention to her.

In the Elizabeth Taylor file there is an interesting event recorded. One day she was complaining of severe pains in her legs so the studio brought a wheelchair to the side of the set, in which she’d rest until it was time for her to go before the camera. But at the end of the day, when a young actor she had a crush on came over to visit from another set, she jumped out of the chair and ran over and threw her arms around him, revealing no trace of a limp.

This doesn’t mean she was faking or malingering. A malingerer is consistent. He’s acting. He doesn’t forget to fake. He’s doing it consciously, for a purpose. But Elizabeth wasn’t faking. Her pains were real. Her condition was real.

Psychiatrists have a technical name for what was happening to her which simply means that psychological symptoms are changed to physical symptoms. Let’s put it this way: Suppose she had a wish she couldn’t fulfill. Suppose she wanted to rebel, to run away from the set, but was afraid to. So without knowing it she might produce leg pains, which would be her way of saying, “I don’t want to stand on my own feet” or “please, won’t someone support me?”

And because of the illness, she did get attention; the studio was thrown into a panic. And she didn’t have to work as hard. Somehow, somewhere along the way, she began to confuse “panic” with “love.” If people panicked because of what she did—or didn’t—do, that meant that they were really concerned, that they really loved her. Becoming ill or getting injured became the sure-fire way for her to insure this panic-love reaction. Soon, therefore. illness took on magical proportions; it was a way of making people pay attention to her, especially her father.

Her brother Howard, two years older than she was, had a more direct means of handling the situation. When his mother arranged a screen test for him, he showed up for it all right, but first he had shaved off all his hair. This effectively accomplished two things at once: it stopped the test and it discouraged his mother, who never again spoke of a movie career for Howard.

But Elizabeth had no such direct methods of fighting her mother.

That’s the pattern of her whole life: a difficulty in relating directly and warmly to people; a confusion of panic with love. Also, of course, there is her additional and fatal curse—she is too beautiful.

Imagine what that must be like. If you’re told day in and day out that you’re the most beautiful girl in the world—and inside you have not had the time to develop anything else of your own—no convictions, no resources, no independence, no personality—then this beauty becomes your only refuge and your only weapon. Sometimes, people use this weapon against you, and this makes you cry out, “I’m an actress. I wish they’d stop talking about my being beautiful. It makes people ignore any talent I may have.” But in a crisis you yourself always fail back on your beauty, your most dependable weapon.

Yet, ironically, you’re frightened at the thought of having to meet people, scared that in the mirror of their eyes you’ll find out that you’re not beautiful, after all. So you’re late for appointments, or break them completely. Why? Because you’re doing and redoing your make-up, making certain you’ll be beautiful.

Elizabeth Taylor’s own words in this regard are most enlightening. “What do I do for so long? Well, I tint my fingernails, then my toenails. I cut my hair. I pluck my eyebrows. I brush and rebrush my hair. Also, I do all my daydreaming when I’m making up. I sit with lipstick in hand reliving a scene that took place last week, wishing I’d said that instead of that.”

Daydreams. She had little besides her beauty and her daydreams. A child in a woman’s body, a girl with no preparation for normal life. And suddenly this child-girl is a bride. Is there any wonder that her marriage to Nicky Hilton was over in two weeks, although it dragged on for months?

After her marriage broke up, she didn’t go back to her mother. She moved from friend’s house to friend’s house to friend’s house. It was during this period that she dated an older divorced man—Stanley Donen—and contracted a most significant illness, colitis, and discovered she had a tendency towards ulcers. (Colitis is an inflammation and spasms of the large intestine.) For months she could eat only baby foods.

There are three illnesses that psychiatrists—and even the most old-fashioned physician—label “psychosomatic” (or, to use the more scientific term, “psychophysiological”)—a characterization of diseases which result from psychological strain and tension. These illnesses are asthma, colitis and ulcers.

It is of significance that her colitis cleared up and she was able to throw her baby foods away as soon as she started going with Michael Wilding, the first of a series of “forbidden men” in her life. Her revolt against authority had begun with her discovery (never conscious, but a discovery nevertheless) that illness equals panic equals love, and now that revolt manifested itself in a different way, in her choosing the first of many men who didn’t quite fit a parent’s idea of a suitable man for her.

For one thing, Wilding was twice her age. For another, he was the constant companion of Marlene Dietrich, and a girl just doesn’t go after another woman’s man. Definitely, Mike was a “forbidden man.”

But Wilding was also handsome and sophisticated, and then again, he was like her father: mild, a gentleman, soft-spoken and passive. once they were married, Elizabeth Taylor dominated him like her own mother had dominated her father.

Her relationship to the children she and Wilding had was extraordinary in its intensity. She seems to have had so much empathy that she could be like a child herself with them. And when they screamed or threw temper tantrums, she would be so moved that she had to retreat and give them over to their nurse. As she said, “When they cry, I cry.”

When she was younger. she had a similar intense devotion to her pets. But when the animals became unruly and wild, she had shied away.

During her marriage to Wilding the old illness-pattern reasserted itself. Following the birth of her first child on January 6, 1953, she spent interminable weeks in hospitals in California. Denmark and England. After the birth of her second child, on her 23rd birthday, however, she did not become ill. Instead, she sued Wilding for divorce.

Michael Todd. whom she married next, was a very different sort of man. He wasn’t weak, he wasn’t mild, he wouldn’t be dominated. Yet he was another “forbidden man.” He was also much older than she was, more than twice her age. That was important but not the important factor. The important factor was that he didn’t fit at all into her parents’ idea of the right husband for her. He was crude, he was loud, he was aggressive; he was the very opposite of a gentleman.

Todd treated Elizabeth Taylor the way she seemed to want to be treated: like a child. He was the permissive, affectionate, out-going, generous father. He showered her with jewels as large as lollipops. Anything she wanted was hers. “Give me that,” she’d say, and Todd would get it for her. If she’d said she wanted the stars, he’d have paid to have a handful made for her—out of diamonds that glowed in the dark. He made her daydreams and night dreams come true.

The panic-means-love pattern did not disappear completely. There were illnesses and operations, but Todd, the man of strength, almost changed Elizabeth Taylor’s fate. Almost, until that night his plane crashed into the side of a mountain and he was killed.

After Todd’s death Elizabeth Taylor was heartbroken with grief. Dark, dismal grief. For in that one death the man who had both taught her how to love as a mature woman and had given her the childhood she never really had, died. Then along came Eddie Fisher.

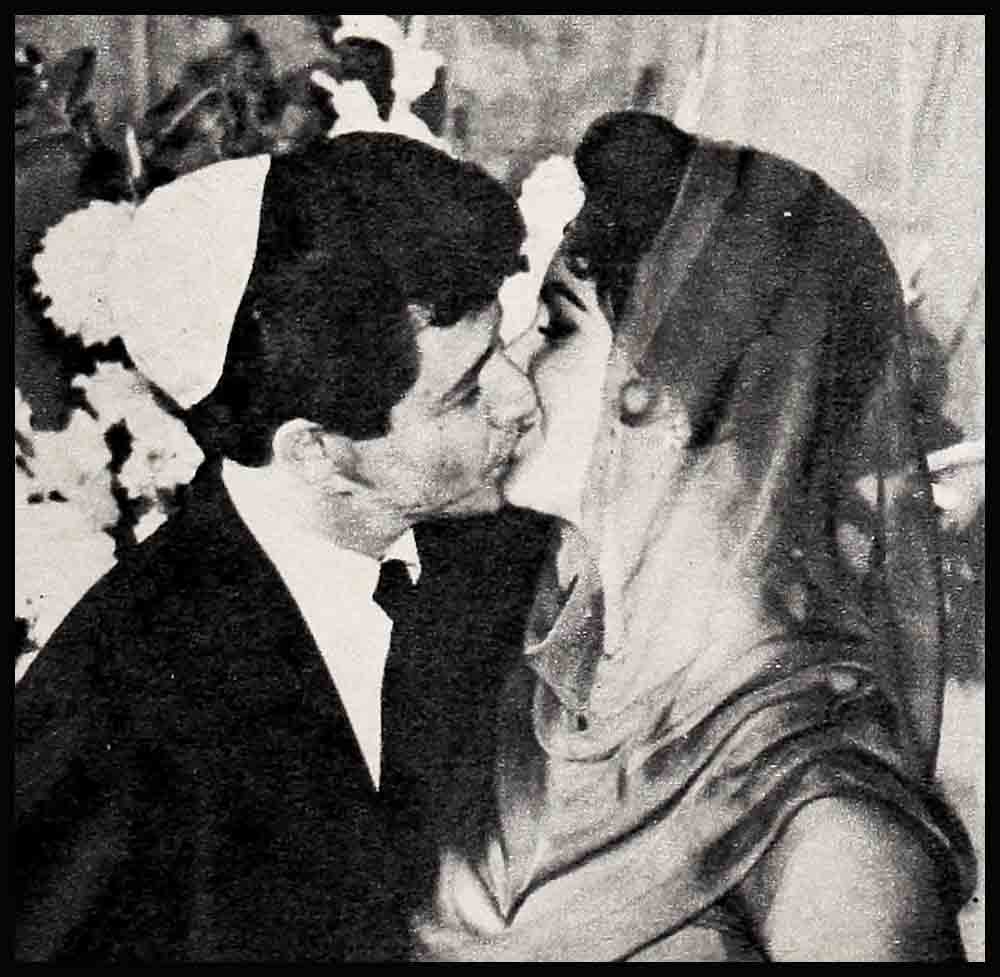

Fisher, the most “forbidden man” of all, was married to Debbie Reynolds, America’s Sweetheart. Fisher was the father of two children. This was the man whom Elizabeth chose to replace Mike Todd. A marriage created out of panic, and, in turn, creating panic that wasn’t short-lived.

Panic when the Liz-Eddie-Debbie scandal was smeared across the front pages, and Hollywood big-shots tried desperately to smooth things over!

Panic until Eddie’s divorce came through! Panic at the wedding in Las Vegas! Panic after they were married. Panic from a never-ending flood of hate letters and “drop dead” messages that threatened to drown them.

Panic among studio executives when a rash of ugly rumors (all of them later proved to be untrue) spread over London where Elizabeth had delayed shooting on “Cleopatra” because of a virus she couldn’t shake. She’s unhappy with the script; she’s on a crash-diet because she can’t fit into her costumes; she’s pretending to be ill because she wants to be released from her contract: these were just some of the false rumors rife at the time.

Panic that spread from director Reuben Mamoulian (one paper actually used the word “frantic” to describe him) up to the head of 20th and down to the extras when Elizabeth was rushed to a hospital with a temperature of 103°, which she had been running for twelve days. Panic when her symptoms were diagnosed as meningism.

Panic which gripped the entire world when she lay near death in The London Clinic from staphylococcus pneumonia in both lungs. It was then, if ever, as she spent two long weeks breathing through a tube in her throat with an electronic lung assisting her, that she should have realized she was loved. Not just because Eddie hardly ever left her side night and day, not just because her father and mother were close by constantly, not just because friends and fellow-actors, executives and extras, made pilgrimages to her bedside, but because for every one hate letter she had been sent previously, she now received a thousand get-well letters, all with the same theme: “Our hearts are with you; our prayers are for you. Liz, we love you.”

That night of the Academy Award presentations, when millions watched the TV screen with their fingers crossed and heard the words, “The best performance by a female star,” and then, “Winner—Elizabeth Taylor!” That night, once and for all, should have marked the end of her need of the panic-equals-love formula. She had caused panic—worldwide panic, and she had received love—worldwide love. That should have been the end of it.

But the patterns of childhood—the mechanisms by which one revolts against authority and reaches out for” love—are more powerful than any “should’s” or “must’s”—or than experience itself.

The studio, with millions of dollars down the drain and not one foot of usable film of “Cleopatra,” cautioned, “Take it easy. Get well.” Eddie, still feeling the effects himself of his wife’s London ordeal, tried to insure that she’d have the calm and peace necessary for a complete recovery. Her doctors insisted that she rest and rest and then rest some more.

But little hints of Elizabeth’s rebellion against their orders—and demands—began to leak into the columns (she was staying out too late at too many parties, she should never have agreed to go to Russia, etc.), and little ripples of panic began to wash against those who loved or needed her.

Miraculously, however, the ripples subsided. The Italian shooting of “Cleopatra” started, and everything progressed wonderfully. Elizabeth was being “good”; Elizabeth was in perfect health; Elizabeth was giving the performance of her life; Elizabeth and Eddie couldn’t be happier. The studio was pleased. Eddie was ecstatic and the doctors were contented.

Then, almost without warning, crash! The same old pattern: illness (“Liz Taylor in Rome Hospital”) ; forbidden man (“Liz, Eddie Split: It’s Burton”) ; panic (“Skouras Flies to See Liz As Rift Reports Persist—$20 Million at Stake”).

Time Magazine confounded a confusing situation even more by stating, “Taylor, according to gossip, is merely using the Burton rumors to shield the real truth: that she is mad, mad, mad for her personable director, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 53, who, however, is very busy shooting all day and scripting all night.”

Immediately, however, there were headlines and stories of denial, featuring Spyros Skouras, president of 20th Century-Fox (“Skouras Has Word for It: False”), and Eddie, once the “forbidden” man— now the “forgotten” man—kept insisting rumors of a split were “silly.” But columnists didn’t need a crystal ball to predict that the Fisher-Taylor marriage would end long before Liz completed her starring role as the vamp of the Nile.

Even when they finally flash “The End” at the close of “Cleopatra,” it seems most likely that the Elizabeth Taylor Syndrome —illness equals panic equals love—will go on. There are people all along the way who have been victimized by Elizabeth Taylor’s syndrome, but the Chief Victim, of course, is the actress herself. Some essential element for bringing herself lasting happiness seems to be lacking.

She seems to have no close female friends. Is this an expression of her feeling toward her mother? There have been many men in her life. Does this reflect her early years with her father? She may always be disappointed in love because her dreams may be more than any reality can fulfill. She is not happy with her beauty. She attracts men with it, and then when they cannot live up to her phantasies, she may feel betrayed. When she is most beautiful, she doubts her own beauty. With her difficulty in feeling simply and directly like other women, with her difficulty in recognizing and reacting to feeling in others, she seems unsure that she’s wanted and loved. It is when she sees panic in others—as she did in Eddie Fisher that night in London when she lay near death— that she can have no doubt that she is loved. For it is the very same emotion she saw in her father’s eyes years ago—when the Steel sliver stuck in her own eye, when the sharp pains shot through her legs.

Panic is love, love is panic, illness equals panic equals love; this is the pattern of the Elizabeth Taylor Syndrome—the unbroken pattern that has made “the most beautiful woman in the world” one of the most unhappy women in the world.

—JIM HOFFMAN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1962