“Slim” Pickin’

When, some months ago, the nation’s moviegoers and film distributors decided that Hollywood’s new box-office champion was a lanky, middle-aged Boy Scout director named James Maitland Stewart. Hollywood was delighted. It appeared that now, indeed the unobtrusive were beginning to inherit the movie world.

For James Stewart—long-time heir-apparent but never king—can scarcely be likened to the handsome or many-muscled or debonair buckos who heretofore have occupied the throne. He has, for example, little in common with Tony Curtis, Bob Wagner or Tab Hunter.

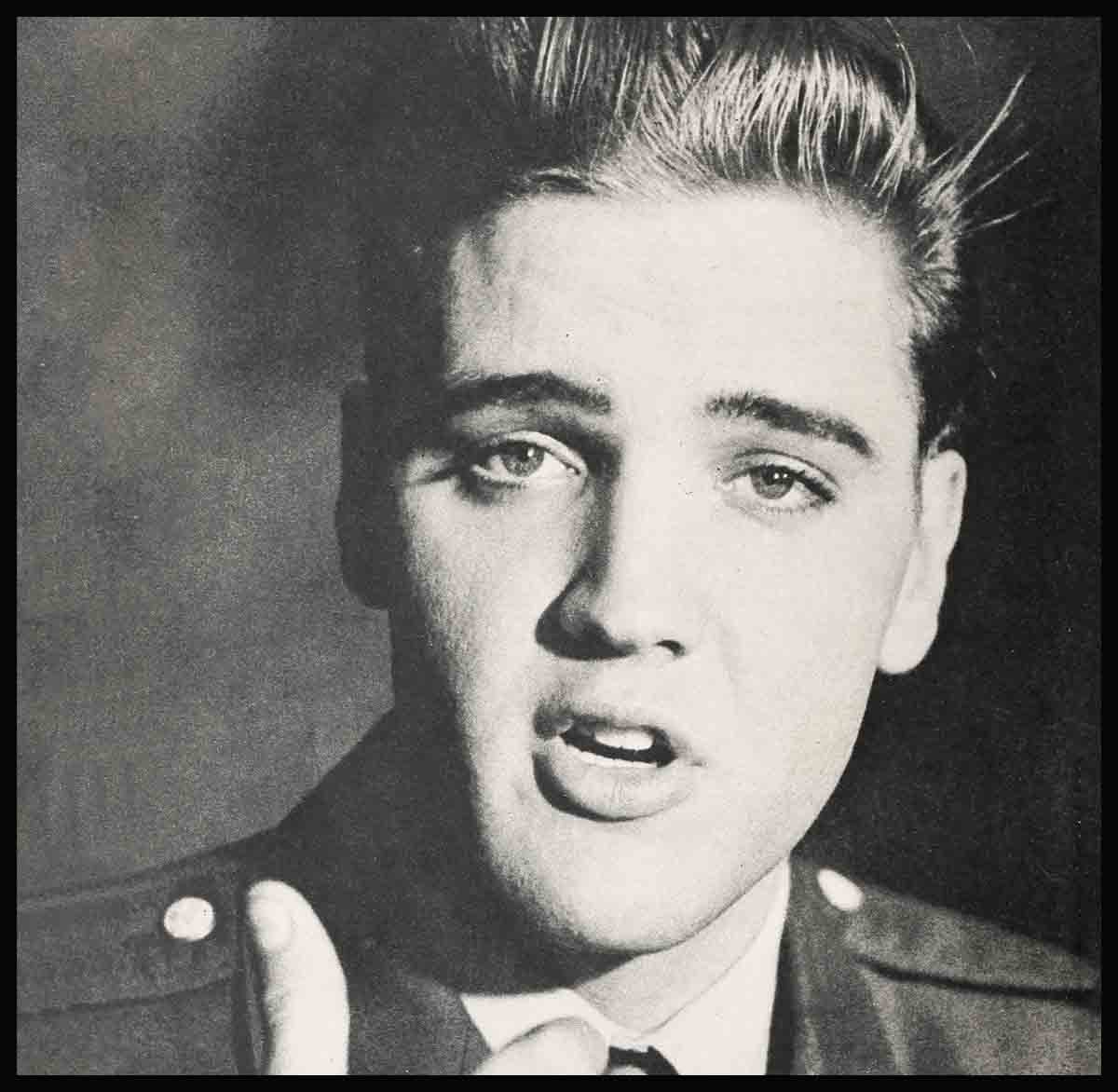

Characteristically, Jim received the news that he was box-office king at home one evening, while mulling over a problem. The problem was: What price extravagance? Jim was sitting in the den of the Stewart home in Beverly Hills, deep in thought. He kept running his hands through his hair—which has turned quite white but at the moment was a shade of orange, having been dyed for his role as Charles Lindbergh in “The Spirit of St. Louis.” Quite understandably, this particular shade revolted Jim, and it temporarily dissuaded him from appearing in public any more than necessary.

The den is the Stewarts’ favorite gathering place, and Jim was at perfect ease as he considered the inanity of spending money hand over fist. On the subject Jim’s (not Jimmy, please) reasoning runs like this:

You can drive only one car at a time. Moreover, taken one at a time, cars can have no more than four wheels and one engine. One car is apt to be as good as another. Therefore, with all due respect to the Mercedes-Benz, why a Mercedes-Benz? The Stewarts have a car apiece—an Oldsmobile and a Ford station wagon—which they have long deemed sufficient.

Similarly, Jim feels a man would look silly wearing one suit over another, purely to demonstrate that his wardrobe is expensive and over-stocked. Jim doesn’t have many suits. He has many dollars—a subject he prefers not to dwell on—but not many suits. However, the suits he has are very, very good. So are his favorite cashmere jackets, which he wears until leather pads have to be applied to the fraying elbows—and eventually leather pads for the leather pads. But never in his life has Hollywood’s current king (a name he would vehemently oppose being called) stinted on quality. For instance, the bronze heads of their four children, which last Christmas were among the gifts he gave his wife, Gloria, were masterpieces. So have been the furs he has draped across Gloria’s shoulders. And the termites currently residing at the Stewarts’ 36-year-old dream house are superb specimens. The bronze heads are forever; the furs of a lasting luster; the termites thriving on a diet of choicest mahogany.

“There are no bargains,” Jim maintains. “You get what you pay for. But extravagance is hard to figure.”

Nevertheless, winning one of the top motion picture accolades, while certainly not a bargain, did come as a welcome dividend. It climaxed Jim’s hardest-working and most rewarding year, which included such top-notch films as “The Far Country,” “Strategic Air Command,” and “The Man from Laramie.” Jim had a comment to make about becoming box-office king. He said, “Well!” And grinned. This is fairly eloquent for Jim. On another occasion he might have said, “Wull,” and then paused, as if thinking out the rest of the sentence.

He was extremely pleased about being named Mr. Big; any actor would be. But Jim, without ever consciously working for it, has nevertheless waited a long time—more than twenty years. There is no reason to believe it was ever one of his major ambitions. Perhaps it never occurred to him that an actor whose screen personality is essentially timid and reserved would pull in many more votes than the crooners, the comics, the lovers, and the cow- licked extroverts. Established stardom, yes. He’s had that for most of his screen career. He’s also received the incidental rewards (especially if you think of a seven-figure fortune as incidental). But the box-office championship came as a joyful jolt.

In spite of all that has come his way, Jim continues to be what he has been for so long. To his friends, he’s a thoroughly simple, uncomplicated man. To casual acquaintances, he seems somewhat intricate and contradictory. He really is a member of the executive board of the Los Angeles Area Council of the Boy Scouts, covering five western states and Hawaii. And he really works at it. He’s also a churchgoing Presbyterian; the family doesn’t miss a Sunday at church unless impeded by illness or minor disaster. As a family man, Jim is a fair but firm disciplinarian of the children, quick-tempered on occasion, especially when he thinks his authority is being directly flouted. He is also a dedicated picnicker and fisherman, a golfer of fair talents, and he likes to play the accordion occasionally.

When Jim speaks, his twangy, nasal speech is deliberate and thoughtful. He is careful with words—but not miserly. He really isn’t untalkative, despite the early phases of his courtship of Gloria, when he found his vocal chords paralyzed. It’s just that he has no use for idle chatter. He likes sense and taste to be integral parts of all conversations. This is a trait which has been known to severely unnerve interviewers, as happened recently. One question asked by a reporter had not been a very good one and Jim, as is his custom, answered it by saying nothing. The silence grew painful, though not to Jim—he was simply thinking. Finally, he said what he thought: “That’s sorta silly, isn’t it?” It was.

Jim, himself, lost verbal control on only one notable occasion, and that was the first time he met Charles Lindbergh, a man as shy and withdrawn as Mr. Stewart. It happened at Romanoff’s (the only place Jim likes to eat lunch out) two years ago, and for once Jim found himself out- silenced. Actually, he had good reason to be awestruck, for Lindbergh had been his boyhood idol. However, Jim realized the mute impasse had to be cracked, and so he cracked it. Still finding himself alone on the platform, so to speak, he began babbling. To this day, he has little idea of what he said. Probably Lindbergh hasn’t either. Nevertheless, they have a great deal of respect for each other.

Jim has been charged—if “charge” it is—with being a personality rather than an actor. In show business jargon, this means that he does not submerge himself in any given role to the extent that the audience is apt to forget they are watching James Stewart. This observation is probably an unjust one, because although Jim’s mannerisms are his, so are anyone else’s theirs, and twenty years of constantly putting them on exhibition as an actor have inevitably made his traits well known to the public.

But that he deliberately injects his personality into a part can be disproved by noting his early preparations for the portrayal of Lindbergh. Jim spent many long hours watching all the available newsreel—some 50,000 feet—of his hero. He studied Lindbergh’s walk, the carriage of his head, his smallest mannerisms, until he knew them cold. Thus, if he appears again to be James Stewart in “The Spirit of St. Louis”—it will have to be because Lindbergh is imitating him!

As a matter of fact, Jim very nearly didn’t get the Lindbergh role. It took two years for it to happen, and then it happened in two minutes. Leland Hayward, the producer of the picture and one of Jim’s closest friends, was pretty convinced he wanted an unknown for the part. Well, he had considered Jim but, rather privately, thought he was too old for the part. Then, too, Hayward hadn’t the slightest idea whether Jim would be interested, and professional ethics had prevented Jim from saying so. But, just as privately, Jim wanted the part badly. As a boy, not only had he worshipped Lindbergh, but in May of 1927, when Lindbergh had taken off for Paris, Jim—clerking in his father’s hardware store in Indiana, Pennsylvania—had placed his self-built model of The Spirit of St. Louis in the store window and periodically posted bulletins of Lindbergh’s flight,.

Now, one night twenty-seven years later, things came to a head. The James Stewarts and the Leland Haywards, along with Jim’s father, Alexander Stewart, and his new bride, were dining at Chasen’s (where the Stewarts prefer to have dinner out). The Lindbergh picture was mentioned and Jim’s father, who’s never believed in holding back, stood up and announced to Hayward and the restaurant at large that his son, and only his son, should portray the great man for posterity. While Jim felt like swooning from sheer embarrassment, Hayward was impressed. Alexander Stewart is an impressive gentleman, and pretty soon the matter was sewed up.

While making “The Spirit of St. Louis” was exciting, Jim also found it extremely arduous, since he appears throughout most of the picture. Also, for endless stretches, while sitting in a cockpit or cabin, he was forced to convey emotion only through facial expressions (as he had to in “Strategic Air Command”). It’s a ticklish job of acting, as well as fatiguing. Then, too, he had to put up with that reddish hair. So much touching up was necessary, Jim finally remarked: “Now I know what a woman goes through!”

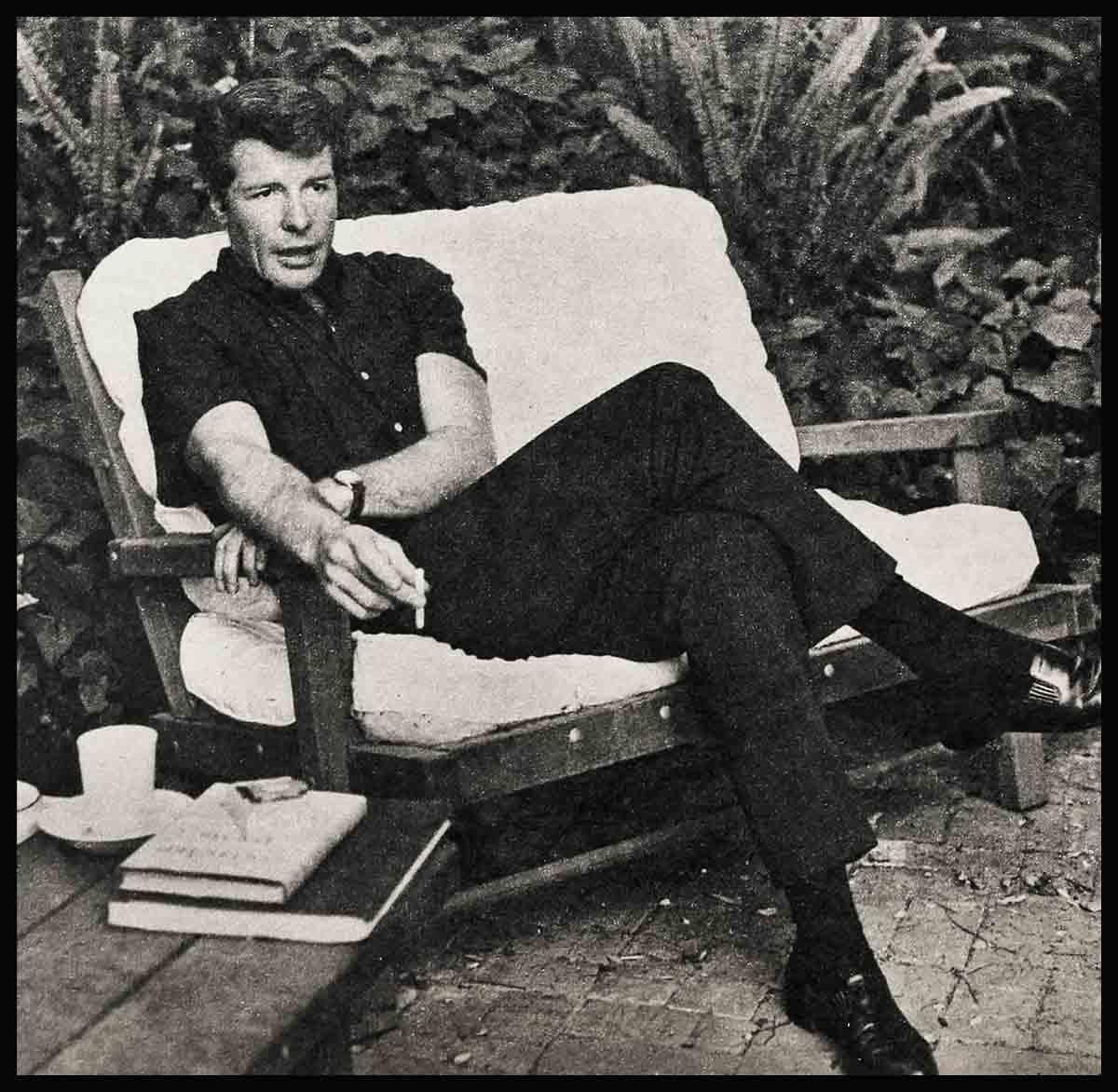

Although he has never completely lost some of his small-town ways, nor fully taken on the highly polished airs of the movie world, Jim has always displayed a keen business sense. The description of the late Wendell Willkie as “the barefoot boy from Wall Street” aptly applies to Jim, too, for he knows how to make himself a pretty good deal.

Take, for example, his recent negotiations with M-G-M. They approached Jim about making “Designing Woman.” This was before they had decided to put Grace Kelly in the picture, too—and, of course, before she had contemplated becoming Princess of Monaco. Jim, according to all reports, said he’d sign if he could have Grace Kelly—to which Metro hastily agreed—both, he went on, in “Designing Woman” and on loan-out for whatever picture he decided to do next. Before anyone knew it, Metro had agreed again—then they went about for days muttering, “What happened?” The barefoot boy from Princeton had scored again.

Gloria Stewart is also an admirer of Grace Kelly’s screen abilities. In fact, once she was fairly dazzled by them. Referring to the famous kissing scene Grace did with Jim in “Rear Window,” Mrs. Stewart said, “She went over him like a vacuum cleaner!”

Jim has seldom subjected himself to making personal appearances—not because he dislikes being in the spotlight, but because he refuses to be personally exploited. However, his strong feeling about good international relationships, plus his intense curiosity about other countries prompted him to agree, during a recent trip to Japan, to appear at a Tokyo theare during the run of one of his pictures. Also to his credit, Jim was still cheerful after being informed that his appearances would begin at 8:30 in the morning, the time Tokyo movie houses open. After every show that day, Jim followed his screen image onstage—an experience which would dismay even veteran vaudevillians.

Apparently, this created a great deal of good will among the Japanese. Soon after Jim’s appearance, movieman T. Ise of Tokyo wrote to an official at Paramount. “Never before,” the letter read, “has a star of any country brought such wonderful results than the recent visit has any of Mr. and Mrs. James Stewart. Not only from our business standpoint for ‘Rear Window,’ but from the standpoint of people’s diplomacy, the tremendous and heartwarming results given by their visit have been immensely gratifying.

“As various episodes which impressed Mr, and Mrs. Stewart eloquently show, the sincere welcome and good will shown by the Japanese fans were unusually enthusiastic. They, in turn, were so warmly (responsive to) the great heart shown by Mr. and Mrs. Stewart that the results of their recent visit have become so great and so fruitful as have never been witnessed before, for which I wish to express my heartfelt gratitude.”

Forwarding a copy of this letter to Jim, the Paramount executive added: “Dear Jimmy: The above was not inspired by me but is purely spontaneous. Thanks a million.”

Assuming top rank at the box office hasn’t changed Jim much except that it is made him even more happy and grateful to all those who made it possible. Otherwise, he’s the same-as-ever James Stewart. He still likes his sport coats perfectly tailored, his food cooked to perfection—even though he still doesn’t eat all of it. (He absolutely cannot gain weight, Once ordered to a hospital for fattening-up treatment, at a studio’s request, Jim lay in one place for ten days and gorged himself on the chubbiest diet science had devised. Result: He lost five pounds.) He still carries the leather script-holder Rosalind Russell gave him in 1937, when they made “No Time for Comedy,” and he probably always will. He still has no use for phonies, and is tolerant of bores.

It could be said, then, that after twenty years in Hollywood, James Stewart is, in many respects, the same as he was as a boy, growing up in Indiana, Pennsylvania. He always loved planes, and spent much time building models. Today, he owns a full-sized one. Naturally, it’s a good plane and, although Jim doesn’t own an airline, he could probably afford to buy one. And he’s still a camera bug. In fact, his home overflows with photographic equipment.

Jim was a fair-to-middlin’ artist at Mercersburg Prep School, and later, at Princeton, he showed promise of becoming a fine architect. But after graduation, he took an artistic detour and stepped into acting.

Jim’s war record is still noteworthy. He flew on twenty-five bombing missions and rose from private to full colonel in the Army Air Force during World War II.

As with many actors, however, his stretch in the Air Corps took a big hunk out of the middle of Jim’s picture career. But he returned from the war to become bigger and better than ever. He also discovered the various career benefits of the Western. A well-made Western always reaps handsome dividends—especially if its star happens to own part of the picture, and a part of a picture is what Jim can and does command. Besides, he likes to make Westerns and says of them, “They are the true literature of this medium, its greatest natural form.”

The Stewarts have two sons by Gloria’s former marriage and twin daughters of their own. Ronald is 12, Michael, 10, and Judy and Kelly are 5. Although it took Jim forty-one years to join the marriage clan, he has more than made up for lost time. Whenever he speaks of his “family,” his eyes light up and he’s apt to pull out some snapshots for proud display. And he particularly enjoys being told that his twin daughters resemble him.

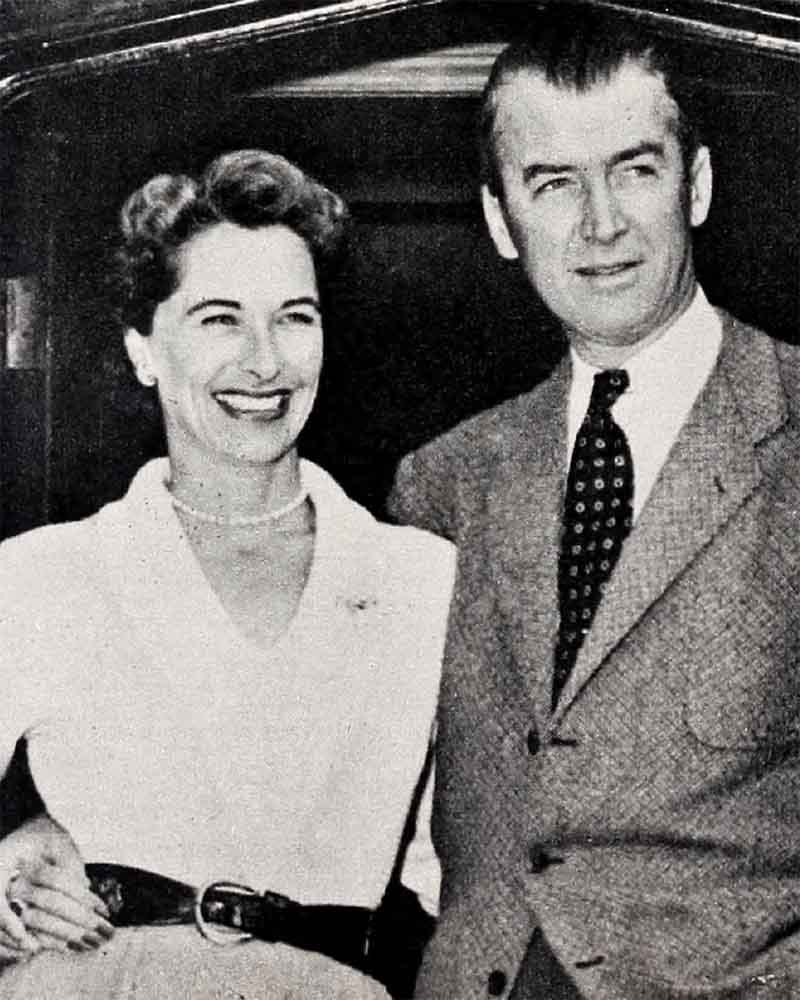

Both Jim and Gloria prefer quiet evenings is at home or with close friends, in contrast to “doing the town.” Jim readily admits he hates being separated from his family, even for a short time, which was frequently necessary during the past year, Making “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” with Doris Day, took him to North Africa and England, then back to this country. And, two days after he finished the Alfred Hitchcock thriller, Jim was off again, to Paris to start filming “The Spirit of St. Louis.” Gloria always accompanies Jim on his foreign locations and always, at home or abroad, her vivacious, witty personality perfectly complements Jim’s reserved, thoughtful manner.

If becoming box-office king had been his goal, it could be said that Jim had a long pull. But Jim has never sought it; it just came to him. Rather, his aim in life has been to do his work right, to live decently and in peace.

Still, Hollywood is mighty pleased with its new “king,” and hopes he will reign for a long time. And there doesn’t seem to be speck on the horizon that says Jim won’t.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1956

No Comments