Why Elizabeth Taylor Turned To Eddie Fisher?

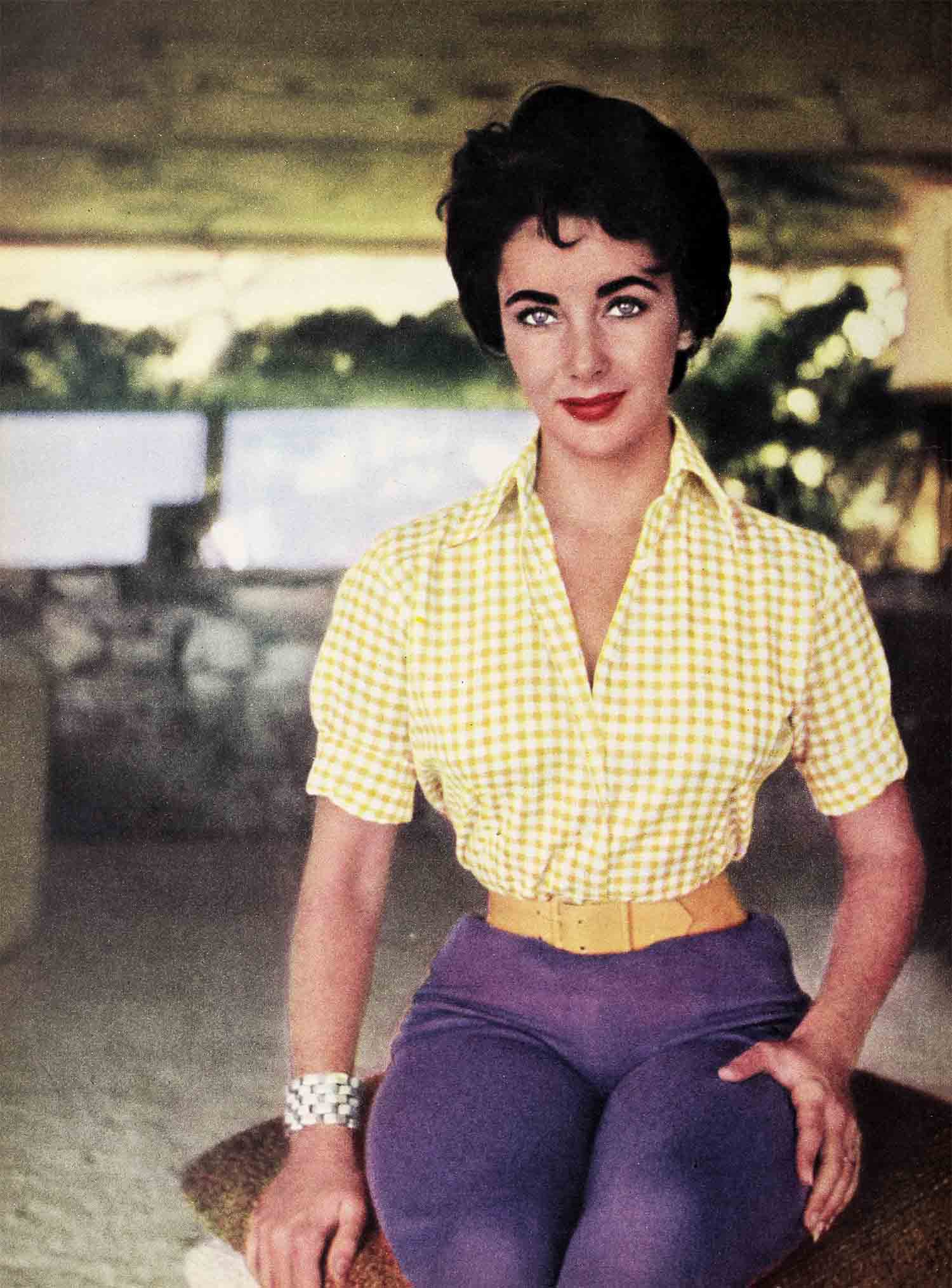

The reporters and photographers pressed forward as they glimpsed the face they had been waiting for. Liz Taylor came down the ramp of the TWA plane arriving from New York at Los Angeles International Airport. Her face, an expressionless mask, seemed a little thickened, perhaps because she held her chin lowered as she watched her footing on the steps. Hot afternoon sun glinted on a jeweled clip that trimmed her high blue turban and on the diamond-studded collar that circled the neck of her Yorkshire terrier, Theresa, which she held in her left arm.

The same California sun burned hot on the tired newsmen, who had been waiting there for hours. “Miss Taylor!” they called out. “This way, Miss Taylor.” She ignored the voices.

Publicity agent Dick Hanley, her companion on the cross-country flight, ushered her rapidly, with a protective hand on her arm, to a special airline station wagon. It sped off; the newsmen ran in pursuit. By the time they caught up, thirty yards away, Liz had left the station wagon and gotten into a waiting limousine brought. by her agent, Kurt Frings.

Through the car window, she looked blankly toward the raised cameras. Out of breath, the reporters clamored questions: “Do you know that Debbie and Eddie are breaking up? . . . Do you expect to see them? . . . Why did you come back to the Coast?” Liz remained silent, until one of the reporters pleaded, “Miss Taylor, won’t you please say something?”

Her lips parted, and out came one cool word: “Hello.”

Did Liz Taylor know then that headlines were naming her as the immediate cause of the trouble in the Eddie Fishers’ household? If she knew, she did not show it. She did not look upset—merely annoyed, as if the voices and questions were coming from another world, which did not concern her.

They were coming from the real world. But that has never seemed quite real to Elizabeth Taylor, who has spent most of her life in a sheltered, unreal world all her own—a soft, comfortable, pretty world, with her beautiful self at the center. It became a fabulous kingdom while she was married to Mike Todd; yet Mike did not create it. It grew up around Liz when she was a little girl, a child with a shining, spiritual sort of beauty. Everyone she knew tried to keep her safe inside her world, and this protection she accepted serenely, as a matter of course. There was only a hazy dividing line between her own life and the make-believe life she lived on the screen, where everything always turned out happily.

On the screen, the twelve-year-old Elizabeth rode a splendid horse to victory. When the picture was finished, a studio representative told her, “We have a present for you, Elizabeth.” She was led to a stable, and there was the horse, towering over her. to put her arms around its glossy neck, and she felt a soft muzzle rubbing affectionately across her shoulder, as if to

say, “Yes, Elizabeth. I’m real, I’m yours.”

But all the events inside her special world didn’t go on turning out as happily as a smoothly written script. can be given presents; a woman can’t be given a successful marriage. On one of the first nights of the honeymoon, an eighteen-year-old bride shouldn’t be alone in her stateroom. But Elizabeth was. She huddled in a brocaded chair in a luxury suite aboard the Queen Elizabeth and fingered the chiffon of her negligee and sniffed quietly, hearing the whisper of the sea outside the portholes and the music of the ship’s orchestra, up on the deck where Nicky Hilton was gaily gambling.

The scene was very badly written, so these pages in the script were torn up and thrown away. After divorcing Nicky. Liz could again play the beauty pursued by dozens of adoring men. Or, when the time came, she could play the cherished wife of an older man, the mother of his sons—a charming picture. Life with Michael Wilding promised peace and stability. But the picture was spoiled by vulgar little details of real life—like money. Wilding was an actor of some stand- ing, but even back in England and most particularly in Hollywood Liz far overshadowed him. When the hurt to his normal male ego canceled out Mike Wilding’s usual good nature, arguments shook the stability of the marriage. And when he kept quiet and took the hurt. the peace of the household sagged into dullness. Not yet twenty-five, Liz refused to settle down in such a world.

Ana then she met Mike Todd. Life with this Mike promised everything except dullness. Yes, they quarreled. Later, Liz was to say tenderly, “Our fights—and we had plenty—were a sort of love-making.” Liz and Mike Todd quarreled even while they were courting. And, as always, Liz sought the comfort she had been brought up to expect.

One evening, a date with Todd broke up in a storm of angry words, and Liz fled home by herself. The house was silent; little Michael and little Christopher were asleep upstairs. In the living room, Liz fretted and worried and finally picked up the phone and dialed a familiar number. Eddie Fisher’s sleepy voice answered.

“Eddie, it’s Liz. I’ve just had the most awful fight with Mike. The things he said—”

“Aw Liz, it’ll blow over. you’ll hear from Mike.”

“But I’ve just got to talk to somebody. Can you come over?”

It was after midnight. On the phone, Liz could hear snatches of Eddie’s voice: “Liz . . . sounds upset . . . wants me to . . .” And she could hear the gentle murmur of Debbie’s voice.

Eddie came over. He sat beside Liz on the couch and gave her the soothing words she wanted to hear: “You know Mike loves you. He didn’t mean it. Any minute now, that phone’s going to ring.”

As far as Eddie Fisher was concerned, Mike Todd could do no wrong. “My boy,” Mike called him. While Mike’s boy and Mike’s beloved talked together, thoughts of the quarrel melted away. It was two in the morning when Eddie patted Liz’s hand and said, “Everything’s going to be all right. Want me to make some coffee?”

“Tea, please.”

Eddie was in the kitchen when the phone at last did ring. Liz leaped for it, whispered, “Hello,” and heard the rough-edged voice she’d been longing for: “Liz, baby. I’m sorry.”

At that moment, Eddie sang out, “That’s Mike, isn’t it? Hey, where do you keep the tea bags?”

The voice in Liz’s ear exploded into a roar that made her hold the receiver away. “Who’s that with you?!!”

In the happy times that followed, the incident made laugh material for the foursome: Liz and Mike, Debbie and Eddie. “Who’s that with you?” became a running gag.

It was Mike with Liz, Liz with Mike, always. As Mrs. Michael Todd, Liz saw her world expand gloriously to make the earth their kingdom. Her whim was law, but she had no important decisions to make, no big responsibilities. Mike was her king. Did she want to see the dancing bears in the Moscow circus? Did she want to buy a $3,000 ball gown in Paris? She saw the bears; she bought the gown (and found when she got it back to New York that it was too tight). There was nothing smug and pompous about their enjoyment of luxuries.

If reality threatened to break in, Mike was always there to shield her. In the hospital, fearing that she might lose their baby, that her own life was in danger, she felt his big hand close around hers, and heard the reassuring words: “You’re my little girl. Nothing’s going to hurt you.” She believed him, and baby Liza entered their world.

But at last reality did smash in, and Mike Todd was not there. It was on a night of rain; Liz had gone to bed after waiting for a phone call that never came, a call from Tulsa, which was to have been Mike’s first stop on the flight across the country in his private plane. She slept fitfully. In the morning, Dick Hanley and Dr. Rex Kennamer came to her door. Before they spoke, she knew what they had come to tell her.

For months, the moments after that kept recurring in nightmares. The pat-pat-pat of bare feet running frantically through a house suddenly filled with terror. A voice screaming wordlessly, senselessly—her own voice, but somehow apart from her. Fingers scrabbling at windowpanes, at a closed door. She wanted to get out of this nightmare of tragic reality and go back to her own safe world, where the phone would ring and she would hear Mike’s voice.

The friends were still there to help and comfort her. Debbie Reynolds, saying, “What about the children? Liz, let them stay with me for a little while.” Eddie Fisher, with her on the long flight to Chicago, with her at Mike’s graveside. Her brother, Howard, taking her out of the terror-haunted house to stay in his San Diego home, with her children. When Liz finally went back to work, studio friends closed in around her to shelter her with kindness. Her dressing room was filled with the scent of red roses, gift from her director and fellow players, whose card read: “You are deep in our hearts.” And there was a small bunch of violets from the crew, men who had known her as a twelve-year-old.

On the set, Liz at first choked and stammered over lines that echoed reality too sharply: “You don’t know what it is to lose someone you love.” But soon she felt at home among the lights, microphones, cameras—familiar and reassuring to her.

When the picture was finished, she plunged into a search for the way back. In Palm Springs, she had been happy with Mike. So she went to Palm Springs, a lush green miracle among the bare sands and mountains. But the palm trees and the brilliant flowers now looked garish and dead; Mike wasn’t there. She had to be taken home in a state of nervous collapse.

Liz flew to New York, and again friends greeted her. There was Monty Clift, who’d been through troubles of his own. His sensitive face lined with the understanding born of hard knowledge, he told her, “Liz, there are some things you just have to learn to live with.”

They were having dinner at the Luau, where the exotic food and the colorful Hawaiian decorations are meant to create a holiday mood. But Liz suddenly saw herself there on an earlier evening, wandering into the little shop connected with the Luau, and exclaiming over a straightcut, slit-skirted dress.

“Whaddya call that?” Mike had growled.

“It’s a muu muu. Oh, Mike, I’ve got to have it!”

“All right, honey. Natives!”

Mike’s voice was all she could hear; Monty’s receded into mere sounds. She couldn’t bear to stay in the Luau a moment longer. “Monty, I want to go home, please.” She fled from New York, back to California. Places weren’t enough; without Mike, they were nothing.

One evening while she was having dinner with Debbie and Eddie at their house, they were talking eagerly about his coming night-club date in Las Vegas, at the Tropicana Hotel. “Coming to Vegas for the big night?” Eddie asked Liz.

“You know I am. I wouldn’t miss it!”

And Liz was there at a ringside table when the music blared out an opening theme and Eddie came onstage. She applauded each number with real enthusiasm. At the lavish party that the Tropicana management threw afterwards, she found a moment to tell Eddie, “Mike would have been proud of ‘his boy”!” Now she could say the beloved name without tears.

Sympathy had gone out to Liz before this, but at the party her friends watched her and felt a load lift from their hearts. “Look at Liz, will you? She’s certainly her old self again.”

Liz had found the way back—not through places, but with people. She danced with Rock Hudson, smiling, at ease; she danced with Arthur Loew, Jr., her escort that evening. In Arthur’s company, she almost felt like a teenager again, because they’d been part of the same crowd in the days before her first marriage. They shared pleasant, trivial memories: “Remember the time we were over at Janie’s and you dropped the hamburger into the fire? Remember . . .”

It was Arthur who introduced Liz to the sun-drenched, quiet town of Tuscon, Arizona, hidden away in the mountains. She had come there for the first time only two weeks after Mike’s death, so weak that she had to be helped off the plane. This town, rousing no memories of Mike, offered her a true refuge. The people and the press of Tuscon shielded her with an amazing conspiracy of kindness: no flash bulbs, no prying questions, never a word in the papers. She was simply accepted as a welcome visitor, and she kept coming back.

The town had had a deep meaning for Liz ever since she first entered the Tuscon home of Arthur’s sister, Jane Morse. Riding was Jane’s favorite pastime, and she had promptly taken Liz out to the stables. As soon as the doors opened, the air was full of the strong, earthy smell of horses and hay and leather. To Liz, it was the odor of her childhood, and she suddenly felt safe again, he little girl with her arms around the neck of the splendid horse that had been given to her for her very own.

Anxious for her children to know such a friendly, outdoor life, Liz began bringing them on her visits. Eventually she decided to rent a house in Tuscon. She was just about to move in when the idyll was shattered by an unlucky mistake: The local paper, in an otherwise discreet and sociable article about the new neighbor, gave the street address of the house.

The article came out on Saturday. On Sunday, crowds of idle, curious tourists—not townspeople—swarmed up and down the street, looking for Liz, thinking she had already moved in. Teenaged kids drove by the house, honking their horns, calling out, “Hey, Liz! Can I have an autograph?”

Reality had crept into her refuge, reminding Liz that she was a celebrity, sentenced to live in the spotlight. She couldn’t go back to Tuscon. All right, then—she would vacation like a celebrity. She cabled for a reservation at the Hotel du Cap in Antibes, on the French Riviera. And perhaps that’s where she should have gone. Perhaps three lives would have been happier if Liz had gone to Antibes . . .

Confusion over her passport delayed her, to begin with. When she opened the safe-deposit box and took it out, she read with a shock: “Mr. and Mrs. Michael Todd.” She had forgotten that she and Mike had a joint passport. Forms were filled out and sent through; a passport for Elizabeth Taylor Todd arrived. She flew to New York to start the trip—but dawdled around there.

On the Friday before the Labor Day weekend, Eddie Fisher called her at her hotel suite. She wasn’t surprised to hear his voice; she knew he was in town for discussions about his TV shows for the coming season.

“You won’t believe this,” he announced, “but Grossinger’s is opening the indoor swimming pool at long, long last. You are hereby invited to the ceremonies.”

“Eddie! What are you talking about? I don’t understand a word.”

He chuckled and explained. Grossinger’s, famous Catskills resort, a favorite among showpeople, had been building an indoor swimming pool—or at least talking about building one—for years and years. A model of the pool had been displayed in the lobby for so long that all the regular guests joked about it. “Now,” Eddie went on, “it’s really finished, and Jennie Grossinger’s asked me up for the opening. I’m driving up Sunday afternoon with Danny Welks. Want to come along?”

“Well . . .” Liz said. “I don’t know whether—”

“Come on! It’s wonderful country, and the weather forecast sounds fine. You”ll love Jennie—love the place. It’ll do you good.”

“All right,” Liz laughed.

“We’ll pick you up about four or four-thirty. Okay?”

“Okay.” Shaking her head in amusement, Liz hung up. She’d never been to Grossinger’s and couldn’t really picture what it was like, though she knew it had strong associations for Eddie: He had gotten his first break as a singer there; he and Debbie had been married there.

Well, at least it would be something different for Liz. The French Riviera could es she had been there before—with Mike.

It was almost dark when they arrived. From the many buildings of the sprawling resort, lights glimmered through the trees and the cheerful chatter of a holiday crowd drifted out. The car kept going, to a secluded row of private homes. Among them was the Grossingers’ own house, where Liz and Eddie and Danny were to stay.

When the three entered the living room—wide-windowed, furnished and carpeted in soft shades of green—Jennie Grossinger greeted Liz warmly, taking both her hands. “You’re just as beautiful as your pictures. Now—you’ll want to change for dinner. You’ll be at our table.” Her tone was cheerful and brisk, with only a hint of the solicitude that everyone showed toward the young widow.

Every head turned when Liz, in a simple black cocktail dress, walked into the spacious dining room in the main building. Paul, the Grossingers’ son, said later: “We’ve had plenty of celebrities here, but not one who ever created the commotion that Liz did. Everybody just had to get a look at her.” There were a few gasps of surprise, but mostly the other guests just stared and whispered among themselves.

With Eddie, Danny Welks and Milton Blackstone, Eddie’s manager, Liz was seated at the Grossingers’ big table. She forgot about all the eyes focussed on her; she had the illusion that she was just dining with a family, in their home. Eddie, too, seemed utterly relaxed, free of the moods that Liz knew (and Debbie knew much better). When Abe Freedman, the maitre de, came over to say hello, Eddie introduced him to Liz. “Abe remembers me when I worked here for thirty dollars a week.”

“And he was glad to get it,” Abe grinned.

For Eddie, these were home grounds. After dinner, the group went through the crowds milling around the lobby and talking, as they usually do at this hour, and strolled along the winding path under the trees to the rustic building that houses the theater. With Danny, Liz sat in the front row and applauded when Eddie was called up to the stage to take a bow. “Labor Day weekend at Grossinger’s is lucky for me,” he said. He didn’t have to explain; almost everyone present remembered that a green kid had once gone up to this stage to sing at this holiday time, nine years before.

And it was in September, too—the 26th, 1955—that Eddie and Debbie were married, at the home of Dr. and Mrs. Etess (the Grossingers’ son-in-law and daughter). This evening, several people asked Eddie casually, “Where’s Debbie?” And he answered each time, “Home in California, with the kids.”

The Etesses also live in the secluded row at the edge of the grounds, but it was too dark to see far when the group returned to the Grossingers’ house. Getting ready for bed, Liz heard the rustle of leaves outside, the fiddling of crickets, the rising and falling buzz-saw of locusts —all placid country noises. New York seemed very far away; so did the Riviera and Palm Springs and Tucson—and California.

Liz slept peacefully through most of the morning, while Eddie and the other men rose early to get a start on the golf course before the weekend crush. There were 1,500 guests at Grossinger’s, and a good many of them jammed in to cheer the ceremonies opening the indoor pool. But late in the afternoon of Labor Day the crowds at play all over the grounds began thinning out, and after dinner the roar of departing cars rose to a crescendo and then died away, and the country noises took over.

Starting to wane, the moon rose late. The green of the Catskill slopes looked black, with lighter slashes marking the trails where skiers would swoop in a few months. There is a walk that honeymooners and sweethearts know, past the tennis courts (deserted now) to the lake. Bathers stopped going there after the outdoor pool was opened; grasses grew again around the margin of the lake, so that there was not a sign of people. (Who wants people?) The still water caught the moon . . .

The sky was gray and rain threatened when Liz and Eddie left Grossinger’s at quarter of four on Tuesday afternoon, for the fifteen-minute drive to the air field built especially for the resort. Without a qualm, Liz stepped into the private plane that Eddie, Welks and Blackstone had rented. There was even a sense of exhilaration at the lift you can feel only in a small plane when the wheels leave the runway. Airborne, it banked, and Liz could see below her the scattered buildings among the greenery, the gunmetal sheen of the lake, all tilted at a strange angle, as if they were about to spill toward the horizon, off the edge of the earth.

The plane leveled onto a course for New York. Liz felt a stirring of anticipation. In New York City, fall isn’t just the sad end of summer; it’s the beginning of the season. A hint of excitement begins to crackle with the first hint of crispness in the air.

That week, at a show-business party in the Harwyn Club, Liz danced with Eddie all evening. (Queried about this later, she Eddie happens to be a very good dancer, that’s all.”)

Friday evening, Liz and Eddie joined friends Eva Marie Saint and Rick Ingersoll at the Blue Angel for an hour’s chat over champagne. This is a small and intimate night spot, usually crowded. As the party made ready to leave, the headwaiter came over to the table with a whispered word. Liz, Eva and Rick left by the front door; Eddie, by a side entrance. But all four got into the same limousine—and a flashbulb went off before it pulled away.

Front-paged on the Saturday edition of a New York paper, the smiling picture set fire to a gunpowder trail already laid by gossip. Column items kept the sparks running along it toward the now inevitable explosion of headlines.

Liz took off for California at five minutes past midnight, just one week after Labor Day at Grossinger’s. But there was a report of fire (false, it later proved) aboard the big plane, and it turned back to land at Idlewild. Liz had to stay there, at the International Hotel, to wait for a later flight. Phone calls to her suite were fended off, but when she went to breakfast, the reporters were waiting, to serve her questions along with her orange juice and coffee.

“Miss Taylor, why were you and Eddie in New York at the same time?”

“I’ve been here on a vacation. just happen. We made no plans.”

“Why are you going to California?”

Through clenched teeth: “Because I’ve got three children there.”

“Are you in love with Eddie?”

“That’s a stupid question! I’m not going to dignify it with an answer.”

“Are you going to see Debbie in California?”

“Of course I am. Why not?”

“All these stories about you and Eddie must—”

“You know I’m a friend of Eddie’s! Everybody knows that. I can’t help what people say. I think this is all pretty stupid!”

Even Liz could not mistake the picture of herself that was slowly being built up through these questions. It was not a pretty picture, and she refused to look at it. To her, it seemed utterly false and unreal.

Meantime, while Liz had been sleeping at the International Hotel, Eddie had reached California, on a flight arriving at 2:40 a.m. California time. Liz’s plane finally took off at eleven minutes after noon, New York time. While it crossed the continent, Eddie and Debbie came face to face. And when Liz’s plane touched down, at 5:30 p.m., California time, the afternoon papers were out with stories of the bitter quarrel in the Fisher home.

Chased to the limousine by the newsmen and finally argued into speaking, Liz said, “I haven’t read the paper. I don’t know what it’s all about. . . . I don’t know if I will see Eddie and Debbie tonight. I just don’t know. . . . I only planned to be gone a couple of weeks, and I’ve already been away that long. I had to come back Se a film, and I miss my three kids.”

But Liz didn’t go directly to her children. With the reporters’ cars in pursuit, the limousine went out La Cienega Boulevard into Beverly Hills. It was believed that Liz had a reservation for one of the $150-a-day bungalows at the Beverly Hills Hotel. The limousine did take her to the hotel, and Liz hurried alone through the lobby. Suddenly, she turned into one of the banquet suites, where a party for Mexico City publisher Carmen Figueroa was in progress. Startled guests saw Elizabeth Taylor whip across the room, her brown wool dress floating out behind her, the little dog Theresa still held in one arm. Liz went out through a side door—and vanished. The press had been successfully thrown off the trail.

While headlines announced the Fishers’ separation, Liz’s whereabouts remained unknown. Actually, there had been a second car waiting to whisk her to agent Kurt Frings’ home in Beverly Hills. If Debbie Reynolds discovered that she was staying at this mansion and called her there, Liz did not come to the phone. But after a day had gone by, Liz did consent to give one interview—and nearly everyone found her words shocking: “Eddie is not in love with Debbie and never has been.”

Asked again whether she loved Eddie, Liz said: “I like him very much. I’ve felt happier and more like a human being for the past two weeks than I have since Mike died.”

Her own world was bright again; she didn’t want to see what was going on in that vague world outside, where a picture of a very different Liz Taylor was taking shape. Indignantly she said, “You know I don’t go about breaking up happy marriages.” To Liz, the idea was ridiculous; she couldn’t do such a thing—not the sweet twelve-year-old who had grown up to become Mike Todd’s “little girl.”

But Debbie and Eddie were separated. Swiftly Liz added, “You can’t break up a happy marriage. Debbie’s and Eddie’s never has been.”

With these words, Liz may have protected the picture of herself enshrined in her own mind. But people outside were not convinced. Debbie’s mother said bitterly of Liz: “Everybody knows what she is . . . Liz won’t get hurt, because nobody can hurt her.”

In a sense, this may be true. Just once, Liz did take the full force of a terrible hurt. Others have spiritually survived such blows, but Liz’s earlier life had left her totally unprepared, and her feelings may have died with Mike.

In another sense, Mrs. Reynolds is mistaken. There is one person who can hurt Liz Taylor—and that person is Liz herself.

—JANET GRAVES

LIZ CAN BE SEEN IN M-G-M’S “CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1958

What Debbie Reynolds Can’t Forget?