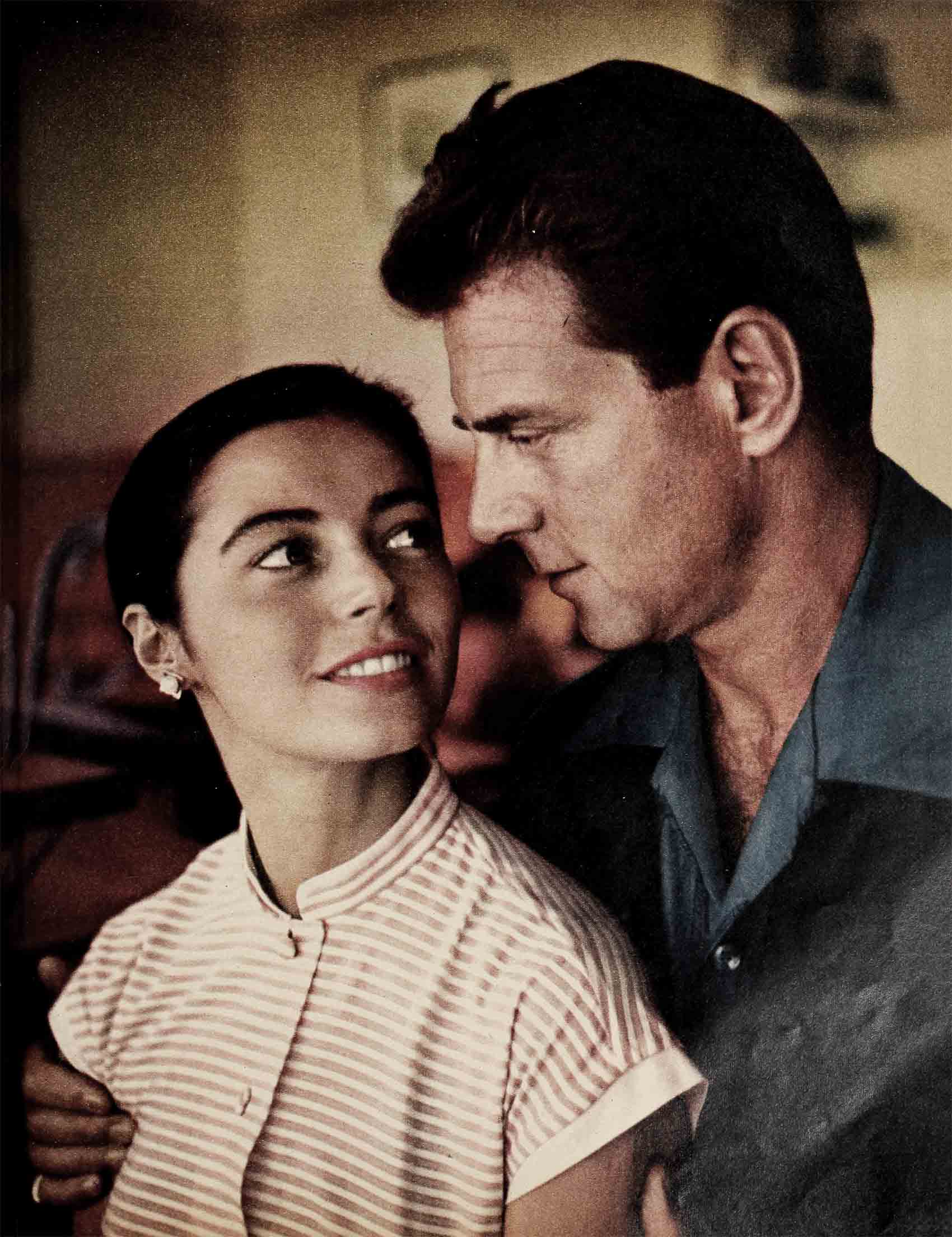

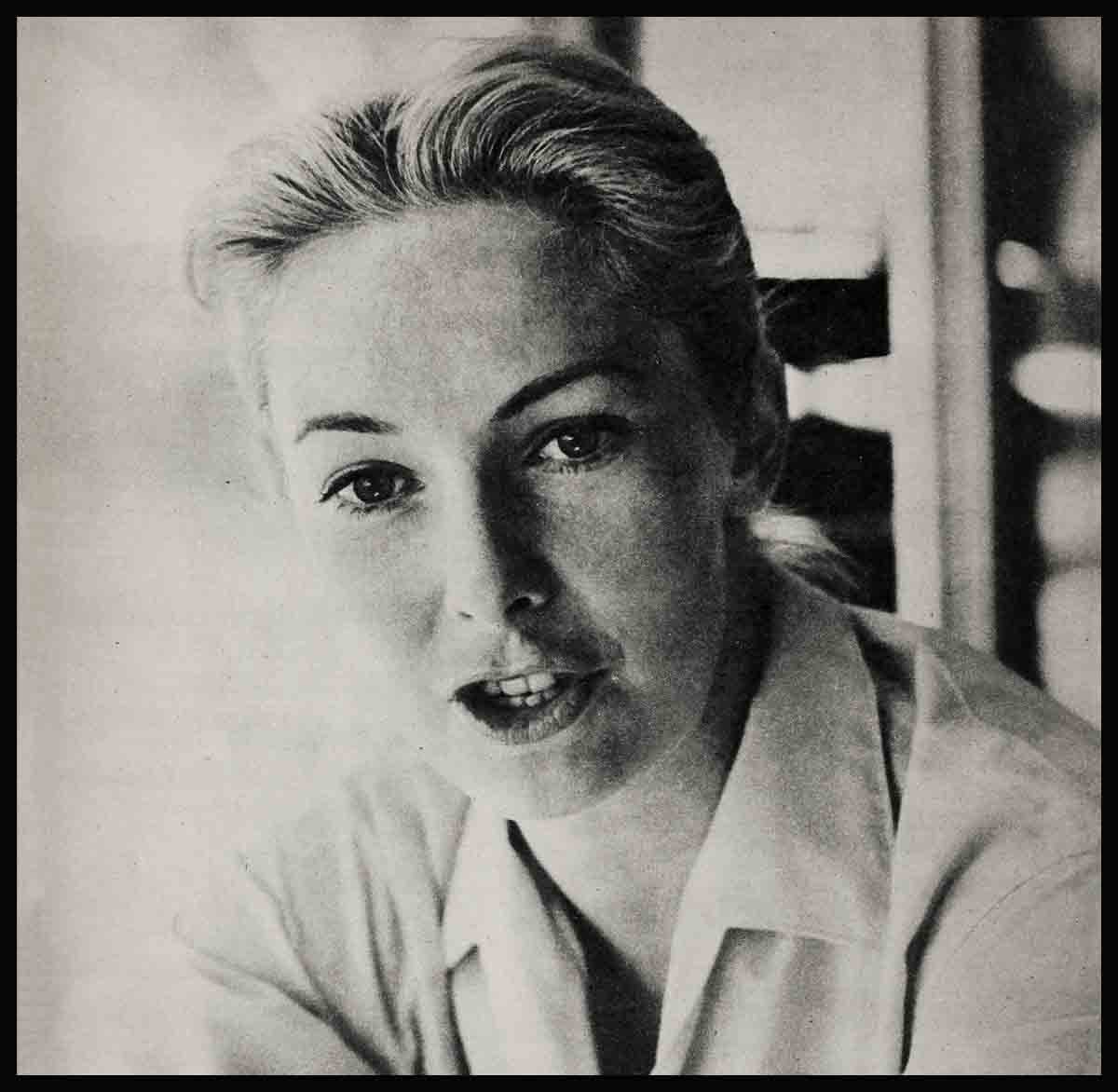

Marisa Pavan: “I Needed To Marry An Older Man”

When Marisa Pavan chose to marry a man twenty years older than she was, the people who did not know her or her husband said many things.

They said that she was foolish and her husband selfish. They said that her husband was separated from her by that most unspanable word—a generation.

They said that Jean-Pierre Aumont was grasping at her youth to replace his own lost youth.

They reminded her that in 1944, when she was a twelve-year-old schoolgirl watching the American Army march into Rome, he was one of those war-scarred men who had fought their way north mile by mile and battle by battle for nearly a year. When she was twelve, he was a thirty-two-year-old married man—who was to become her husband eleven and a half years later.

“In reminding me that my husband is separated from me by incalculable joys and timeless winters of the heart,” Marisa says softly, “they were attemping to shame us, I think, because we had done something that they considered unusual. But I will not be shamed.

“In Jean-Pierre I came unexpectedly upon all the richness and fullness that I did not have. In Jean-Pierre I found a complete man—not just the jagged edges and nervous energy and bits and pieces slapped together into the shapes of younger men I had known.” For the first time in her life Marisa saw a man at peace with himself and his life. She hungered to have this richness, this fullness, this joy near her.

Her friends frowned disapprovingly and said she was foolish. They frowned disapprovingly and said Jean-Pierre was selfish. “Selfish!” Marisa flashes. “How much youth is overvalued in our world! If either of us was foolish, it was Jean-Pierre. He spread his richness over me like a boundless spring of flowers. What did he receive in return?”

In return, Marisa feels, he received a wife still feverishly caught in the grip of the raging impatience, confusion, uncertainty, and solemness that is worshipped under the name of youth. “I think that Frenchmen are known to have made better bargains than this one,” she laughs. Then her face becomes quiet as she presents her philosophy, “I cannot speak for you walking in the darkness with your young love; or you, growing up together day by day, year by year as though some closeness has been bred into you by all the classes in which you have sat together and all the summers you have shared; or you, meeting in the spring of your last collegiate year and falling in love in those two incredible months. I cannot speak for you, but, for myself, I could not have married any of your tanned and self-confident young men. I needed to marry an older man.”

She needed a gentleness and patience and understanding and sympathy that a young man could not have given her. She has always been drawn to men and women older than herself. She’s always felt that young people are too involved with themselves to be able to give of themselves easily to others. They try to change each other, to possess each other. And she dosen’t believe that any person can possess another person, even in intimacy. They can only give to each other freely.

To Marisa—and Jean-Pierre—marriage can be, must be, a perfect communion of two people who understand each other. Perfect communion of mind and body and spirit is not easily won. It must be worked at. It will not fall from the sky.

“My marriage is not yet perfect,” Marisa rushes on to explain. “There are things I do not yet know about Jean-Pierre and things he does not yet understand about me. But already we share a closeness that I do not think I could have achieved with a boy.”

For Marisa, he’s right

To Marisa the essence and joy of marriage is sharing this closeness. It is knowing that someone needs you and that you need someone and not being too proud or too afraid to say this to each other. It is love and tenderness and understanding.

“What is true for me and for my marriage will not be true for others and for their marriages. I can only speak for myself. I can only say what is right for me.”

And for her, Jean-Pierre is right. She needs a husband who is also a friend, a companion, and a teacher. She needs a husband who is strong and who can teach her how to be strong, too.

Jean-Pierre is strong. He is satisfied with life. He has tasted even its bitterest moments, and yet he still finds life good. He has learned to enjoy life.

In the Sanskrit ’Salutation To The Dawn’—a poem in which the ancient people of India spoke their praise to each new day—is this line: Today well lived makes every yesterday a dream of happiness, and every tomorrow a vision of joy. Marisa speaks the words, adding, “I do not know if Jean-Pierre knows this poem, but its words are almost a key to his enjoyment of life. He makes every minute of every day of his life important. He lives each day well.”

To enjoy life—to spend no time in regret or fear—is a difficult thing to learn. Marisa makes things difficult when they are not. She is bruised by words, she is a little afraid of people.

Before Jean-Pierre she stood a while on the sidelines of life, in the far corner where the bright lights and the music and the circle of the dancers did not quite reach. The young men she knew plunged into the circle without waiting for her, and she could not follow them. Then Jean-Pierre came along and held out his hands to her and began to teach her how to enjoy life and how to enjoy people.

A new world

She has always chosen to stay home, rather than to go to a party filled with people she had never met. But all people seem good and beautiful to Jean-Pierre. He does not label them good or bad or dull or stupid. “He has led me also into his wonderful world of people and shown me how each person has worthiness in some way, and how I do not need to be afraid,” Marisa explains, and for a moment her eyes mirror the bright new world JeanPierre has opened for her.

Jean-Pierre understands people, with the kind of understanding that comes from the sorrows and from the winters through which a person has lived, that comes only when a person is mature.

“Because I am not yet completely mature, I am glad to have this maturity by my side to help me grow,” Marisa freely admits. “When I am sad or hurt, he will say, ‘It is not right to be sad. Give each thing only the importance it deserves. Never look at anything as seriously as it appears.’ And because he is too lighthearted to be serious for long, in a moment he will be laughing at something and I will be laughing with him.”

Jean-Pierre has taught her many other things. He has taught her the meaning of love—and the meaning of loneliness. She never knew that she could be as lonely as she was when she left him in Paris a month ago and came to make her present picture, The Eyes Of Father Tomasino.

She would never be happy married to a younger man. “I think perhaps I would be too old for a man of my own age,” she laughs. “I have usually been bored by young men and uninterested in the things that they can find to talk about and in the things that interest them.”

No difference in age

When she is with Jean-Pierre there seems to be no difference in their ages. Because he is older he has known many experiences and many sensations that she has not known, but he shares these with her and makes them as tangible for her as dozens of colored balls. And in everything else—the things they laugh at, the way they think, the pleasures they enjoy—they are of the same age.

“Or perhaps I am a little older than my husband,” muses Marisa. “At times I am sure that I am. I am always the serious one. I am the one who must lock the suitcases and put out the cat and wind the alarm clock or they would never be done.”

On the first day of their honeymoon they were waiting in the San Francisco Airport for the plane that would take them to Hawaii.

“Come,” Jean-Pierre said.

“Where?”

“We’ll hire a car and I’ll show you San Francisco.”

“But the plane . . . do we have time?”

He laughed and took her hand. “If we wait at the airport we’ll just be wasting time.”

“Okay.”

They hired a car and drove through the hills and threaded their way down the narrow streets of Chinatown and stopped the car and stood on the shore . . . and threw a pebble into the bay. They drove over the bridges and back again, and watched the ocean glisten below them in the sun.

She looked at her watch.

“Is it time?” Jean-Pierre asked.

“Yes.”

He drove up one hill and down another. He ran his hand through his hair and started up another hill. Fifteen minutes later he gave up.

“I think,” he said, “that we’re lost.”

They were. It took them another half hour to find their way, and they got back to the airport just in time to watch their suitcases take off for Honolulu.

Absent-minded Pierre

That was not the last time they missed a plane. And they almost missed their wedding in the first place. They were stepping into the elevator on their way up to the judge who was to marry them. Someone shouted, “Jean-Pierre! Marisa!” And ran towards them with a piece of paper in his hand. It was their marriage license. Jean-Pierre had kept it “to make sure it will be safe,” he had said. And he had left it in his bedroom when he picked his bride up to take her to her wedding!

Jean-Pierre is impulsive and absentminded and undisciplined. Once in Paris he decided that he wanted to go to London. He didn’t give Marisa any time to tell the cook or pack a suitcase. And the only thing that kept them from being in London that evening was the fact that he forgot their passports.

The next time they took a trip he very shyly handed the passports to her before they left.

Jean-Pierre is impulsive and undisciplined. But his wife does not like disciplined people. They are too cold. They do not have warmth and fire. And his impulsiveness is part of the joy with which he meets each new day. Even his absentmindedness is part of his enjoyment of life. He cannot remember to catch a plane if there is something else to enjoy.

The two of us . . .

This enjoyment of life—this richness, this contentment that her husband has—Marisa hopes to acquire in time. “I have been married only six months,” Mrs. Aumont smiles, “and yet already there is a certain purpose to living that I did not know before. With Jean-Pierre I find a certain security—not a financial, but an emotional security—that I did not have six months ago. Life has suddenly more meaning and in everything I do, in my thoughts, and in my feelings, there are always the two of us involved.”

Marisa Pavan never asked Jean-Pierre his age. His age didn’t matter. Once some of her friends said, “Oh, you’re going out with such an old man!”

“Oh yes?” Marisa answered, “how old is he?”

“I remember their answers,” Marisa smiled. “One of them said, ‘He is forty-two.’ Another said, ‘He’s forty-seven.’ Another said, ‘At least thirty-four.’ Another said, ‘I’m sure he’s almost fifty!’

“ ‘Oh?’ I said and shrugged. ‘It doesn’t matter.’ ”

Then one evening Jean-Pierre said, “I’m worried, Marisa. You don’t know what age I am.”

“It doesn’t matter, Jean-Pierre.”

For a moment he was very serious. “It does. It hurts me. I can’t tell you. I’ll give you the passport and you can add.”

He reached into his pocket and handed her his passport. Then he turned away and stared out the window. “I am so bad at figures,” Marisa remembers, “I looked at the date and the year. Then I tried to subtract that year from 1956. But I didn’t have a pencil and the figures got all jumbled up. Finally I threw the passport on the couch.

“ ‘Jean-Pierre!’

“He turned back to me.”

“ ‘It’s too much, Jean-Pierre. I can’t count. The figures won’t come out right. And I don’t care! I don’t care!’ ”

And she doesn’t care. He is twenty years older than she, but—“It is Jean Pierre who knows how to entertain me when I am sad, knows how to make me happy, how to handle me, when to compliment me and when to be silent, when to protect me and when to hold me in his arms.” Nothing else matters to Marisa Pavan—Mrs. Jean-Pierre Aumont.

THE END

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1956

No Comments