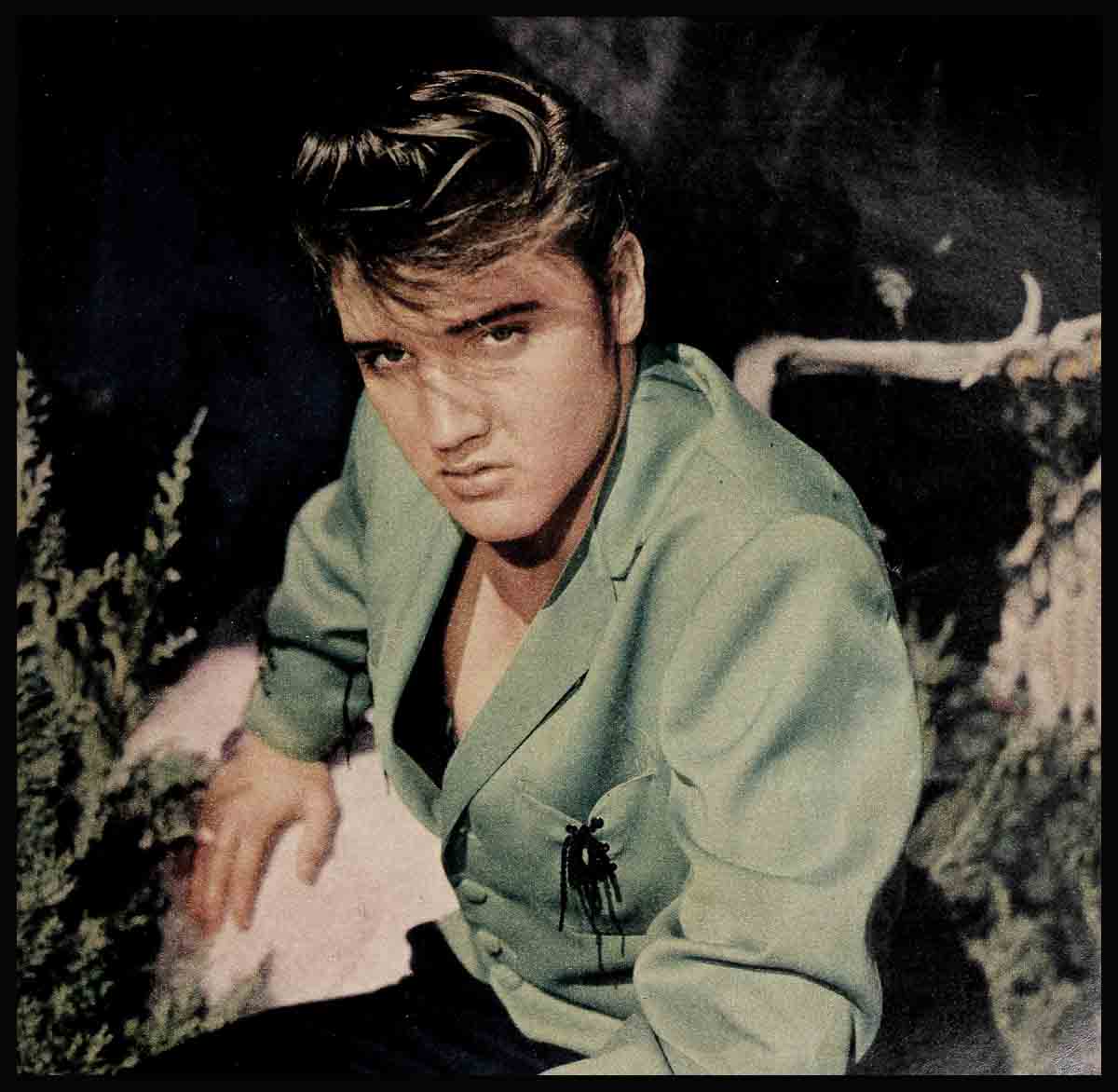

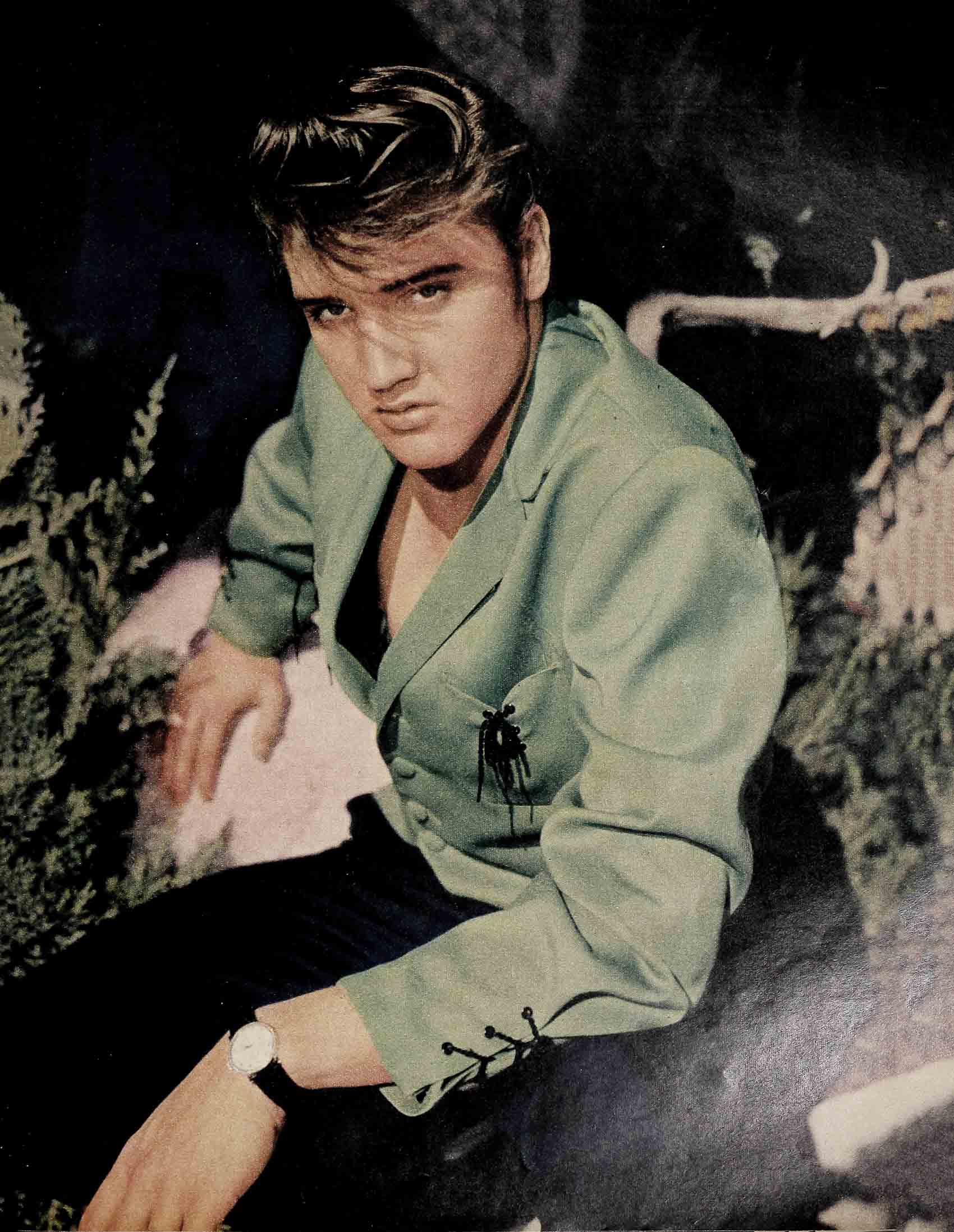

Who Is He? Why Does He Drive Girls Crazy?—Elvis Presley

It was at the Coliseum in Fort Worth, Texas, not long ago. The tall boy on the stage had hardly begun his song, “Let’s Play House,” swaying and twisting his body with the beat, fairly lashing at the strings of his guitar, when his audience of 7,000 turned into a sea of excited girlhood. Suddenly a teen-ager jumped up. “Oh, Elvis, I’m going to die!” she screamed. Other girls rose, shouted and danced as the singer’s voice went into full-throated cry.

“It was utterly fantastic,” said a writer reporting the show in The Ft. Worth Star-Telegram, one of the city’s newspapers, the next day. And it was. But it was nothing new. Elvis Presley has cast this same musical spell through a good part of the rest of a the south and all along the eastern seaboard. He doesn’t even have to be seen, apparently; the mere playing of one of his records seems to be enough to stir up wild enthusiasm. And it’s been like that almost since the day, nearly two years ago, when he quit his $35 a week delivery-truck driving job in Memphis, Tennessee, to go on the road—a nineteen-year-old troubador with a magnetic manner and an atomic baritone.

His rewards have been big. He has four Cadillacs, a canary yellow convertible, a pink Fleetwood sedan, a blue limousine and a light purple Eldorado. His show salary runs to thousands of dollars a week. For a fortnight at the New Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada, he collected $15,000. His first big time recording, “Heartbreak Hotel” (backed by “I Was the One”), sold a million within ten weeks of its issuance last January, and practically every guitar-playing singer in the country is imitating him. And early last May he was signed for the movies in a contract that can well bring him millions over the years.

It’s such a fabulous beginning that Elvis himself finds it hard to believe sometimes. “Man,” he tells you, “I sure hope it keeps up.” So do his parents, Vernon and Gladys Presley, who have been able to retire in a $35,000 home in East Memphis which he purchased for them. But most fervently of all, so do the increasing tens of thousands of girls who crowd the theatres, armories and arenas when Elvis comes to serenade them.

In San Antonio, Texas, they formed a human pyramid trying to reach the high window of his dressing room backstage. In Washington, D.C., those who couldn’t get close enough for an autograph when he sang on the S.S. Mt. Vernon, anchored in the Potomac, had to be led from the boat in tears. And when he played the ballpark in Jacksonville, Florida, kids who did reach him nearly ripped him bare.

What Elvis is like

The young Southerner who is causing this furore is only twenty-one years old now, and of mixed Scotch, Irish and Italian blood. He doesn’t drink or smoke. He has never gambled. But he is tall, a full six feet, with eyes set deep and dark in his head, and features strongly, almost insolently, masculine. His singing style is unlike that of the great crooners or sobbers who have come before him. Elvis just lets go—but with tempo. Some critics call it rock-and-roll. Others say it’s hillbilly. And perhaps the most accurate compare it with tribal chanting. Certainly there is a lot of sex in his voice. Elvis doesn’t soothe his fans—he sends them. When he gets to rolling with “I Got A Woman,” “Long Tall Sally” or “Blue Suede Shoes,” the quivering and fainting begins.

The navy shore patrol had to be called out to quiet his audience when he sang in San Diego recently. At that Ft. Worth concert forty girls had driven over in a chartered bus from Dallas to see him, and two of them exhibited scars on their arms where they had tried to carve his name into the skin with pen-knives. Told of this after the show, Elvis, wearing a lavender sports coat, black dress pants and a pink mandarin-styled sports shirt, shook his head in perplexity. “I don’t get it,” he said.

But he would rather be puzzled than have it stop, because if things are fat for him now his early years, which began on January 8, 1935, in the small town of Tupelo, Mississippi, were on the thin side. “We were never wealthy, but never what you call real hungry,” he says.

A twin, whose brother died soon after birth, and thereafter an only child, Elvis was brought up over-protected, in his opinion. “I couldn’t go out with the other boys, go swimming, or even play away from the house until I was fifteen,” he remembers. What is significant about this is that on his twelfth birthday, when Elvis wanted a bicycle, his mother bought him a guitar instead.

Elvis played it. He wasn’t very good, sounding mostly like someone beating on a bucket lid, as he expressed it. But it got him to singing more than usual, which pleased his folks. They recalled that, at the age of four, he could sing louder than anyone else in the choir. To this loudness he began to add a quality of tone which lent itself to folk songs and won him fifth prize in a Mississippi State Fair singing contest.

There was always a girl

Elvis never did study music, but Be kept up his guitar playing (“I just know a major chord or two,” he says) and attended the L.C. Humes Jr. High—High School in Memphis for six years, during which time he found there was always a girl he couldn’t keep his eye off.

“First thing you know, when I was sixteen and a sophomore, I fell in love with a girl who was nineteen and a senior,” he recalls. “She was taller than I was, and heavier too. But I thought her the most beautiful girl in the world.”

When that girl confirmed what other ones he had previously gone with had told him, that they thought he could sing, he decided to have a recording of his voice made for himself some day.

He went to work after graduating from high school (with average marks) for a precision tool company, moved on to a furniture company where he ran a table shaping machine, and wound up delivering material for the Crown Electrical Company in Memphis. In the meantime

he had saved enough money to have the Memphis Recording Company, managed by a Sam Phillips, cut a record as he sang “I Don’t Care If The Moon Don’t Shine,” and “Blue Moon Of Kentucky,” to his own guitar accompaniment. Phillips, who also issued records under the Sun Record Company label, decided Elvis’ voice ought to be heard around the country.

Actually only a few hundred records were initially distributed, all within a 300 mile radius of Memphis, but the response was so definite that on the strength of it Phillips signed Elvis to an exclusive contract. Lovers of his records began calling for Elvis to make personal appearances, and he decided to try his luck playing the smaller towns through the south and the eastern part of Texas. The first time that Col. Parker, the hill-billy impresario, saw him was in November of 1954, but Parker was busy then managing a tour for the famous Eddy Arnold. A few months later Parker was in Texarkana, Texas, when he happened to hear that a young singer playing Boston, Texas, had pulled more fans in to see him than the town had people. Parker investigated, and this time he signed Elvis to a contract.

The panic is on

Through subsequent months, and in the course of two tours, Elvis, supported by a three-piece “combo,” played a hundred dates, from Washington, D.C. on the north, down to Florida towns on the south, and as far west as Colorado. And without fail he got riotous welcomes. Then, in January of this year, Elvis went national—and the real panic was on. He made an appearance on the Dorsey Brothers’ television show, a network telecast, and was such a hit that he was brought back a half dozen more times.

The first time the Dorseys presented Elvis the girls in the studio audience were shocked into silence. But at his next appearance they were ready for him and swooned and fainted all over the place. By now Hollywood was talking about a screen test. Elvis agreed to come west and make one for producer Hal Wallis.

“How much acting experience have you ever had?” he was asked.

“Never read a line in my life,” he replied frankly.

But the job Elvis did won him a seven year contract with Wallis, binding him to make one picture a year for the producer during this period. By the time he has made two of these films it is expected by the studio that he will be as effective as the late Jimmy Dean was.

This is studio talk, not Elvis’. All he knows is that he enjoyed the day of the test as much as any day in his life, and that when he saw himself on the screen he thought he looked like his parents.

Show business people are usually puzzled the first time they see him. As he comes lumbering out from the parted curtain when he is announced, his guitar hanging low and somehow more like a gun holster rather than a musical instrument, they ask, “What’s the matter with him?”

But when he galvanizes into action, they snap rigid in their seats.

It’s not just looks

It’s not just Elvis’ looks that are provocative—though his 180 pounds of blue-eyed, dark-brown haired masculinity provoke a great deal. It’s also what he says.

Walking out on the stage of the huge Shrine Mosque in Richmond, Virginia, last year, he announced, as he was supposed to do, that his first number would be, “I Was The One.” But then, as was not according to script, he added, “I usually have a quartet to sing along with me on this one. If anyone wants to come up and help me, they’re welcome.”

The next moment there were 300 girls climbing onto the stage, the stage manager was lowering the asbestos curtain to cut them off from the audience so that no more youngsters could crowd up, and an emergency police call had been put in.

Elvis hadn’t meant to start anything. It’s just that he hates to meet folks (and that’s what he considers his audiences) without being friendly and making a little conversation. The same instinct on his part got things off on a wrong footing in Las Vegas at the New Frontier Hotel.

It was decided that a special matinee performance would be staged for young people, who would be charged a dollar apiece to drink Coca-Colas and listen to Elvis—with all the proceeds going towards a $35,000 fund being raised for a night baseball park for the youngsters. Elvis was to sing without fee. The hotel agreed to provide its ornate banquet room and the refreshments without cost.

All went well until Elvis made his entrance and looked over his audience of 700—mostly girls his age or under.

“I’m sure glad to see you all,” he began, “because ordinarily the hotel doesn’t allow anyone in here under eighteen unless they bring their own whiskey.”

That did it. There were peals of laughter and the kids threw themselves into listening to Elvis as strongly as he threw himself into his singing. He did fifteen numbers and then the fun really started. After he went off stage the girls started hunting for him—through all the halls, banging on room doors and calling to him. It was evening before they were finally all hunted up and sent home.

More boy than man

All his appearances, including TV, are going to bring in more money for Elvis per week than most lads his age make in a year. But he is all set with his plans on how to handle his income. “I am going to save a lot and spend a lot.”

Actually, he is more boy than man when it comes to extravagance. Except for the home he bought his folks, and his cars, two of which he uses for traveling, his spending is minor. For recreation he likes to hunt up an amusement park and play the games of chance along the midway, throwing baseballs at a pyramid of bottles or tossing darts at balloons. One day he came home with twenty-four kewpie dolls he had won at a carnival. From time to time he will get gadget-minded. One day he turned up for the beginning of a tour carrying a portable movie projector and a can of 16 millimeter film, including an old Abbot and Costello movie.

“It’s for when I want to relax when I go to bed at night,” he explained. “I’ll shoot the picture on the ceiling and lay there and look at it.”

But for real relaxation Elvis admits he likes girls—or rather a girl. If he can get a chance to go to a dance with one where he won’t be recognized, and if he can get onto the floor with her and close his eyes to dream around slowly—that’s the kind of dancer he is, by the way—he is happy.

He doesn’t want to get more serious than this now because he knows his future still lies in traveling and moving quickly to take advantage of opportunities. That future, as he sees it, should eventually mean acting, and just acting. He is perfectly willing to put away the guitar for good, and even get away from singing, for a career in the movies.

And that’s the way things look ahead for Elvis Presley—except for one thing. His own parents married very young and he admits that the marrying urge can strike him too. “Most any time, I suppose,” he says.

THE END

—BY LOUIS POLLOCK

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE AUGUST 1956