The Dividends Of Courage—Guy Madison

High on a hill in the Outpost in Hollywood tonight, a tall lean man in a tan buckskin suit, shoes removed, pads into a gay new . yellow nursery and bends over a crib. For a while he stands there, quietly looking. And the cares of the day, and the years, fall away.

“Hi, Charlie,” says Wild Bill. “How’s the girl?”

Her name is Bridget Catherine. Or you may call her Wee Belle Hickok. Her father calls her Charlie. Which at first confused their serious Swedish nurse no end. “Why does your husband call the baby Charlie?” she finally asked Mrs. Madison. “Well,” Sheila began, and tried with, “well, it’s sort of an expression. Sometimes he calls me Charlie. It’s a habit. It’s just. . .”

They may say it differently in Sweden, but it’s just that, to Guy Madison, Charlie also means “I love you.”

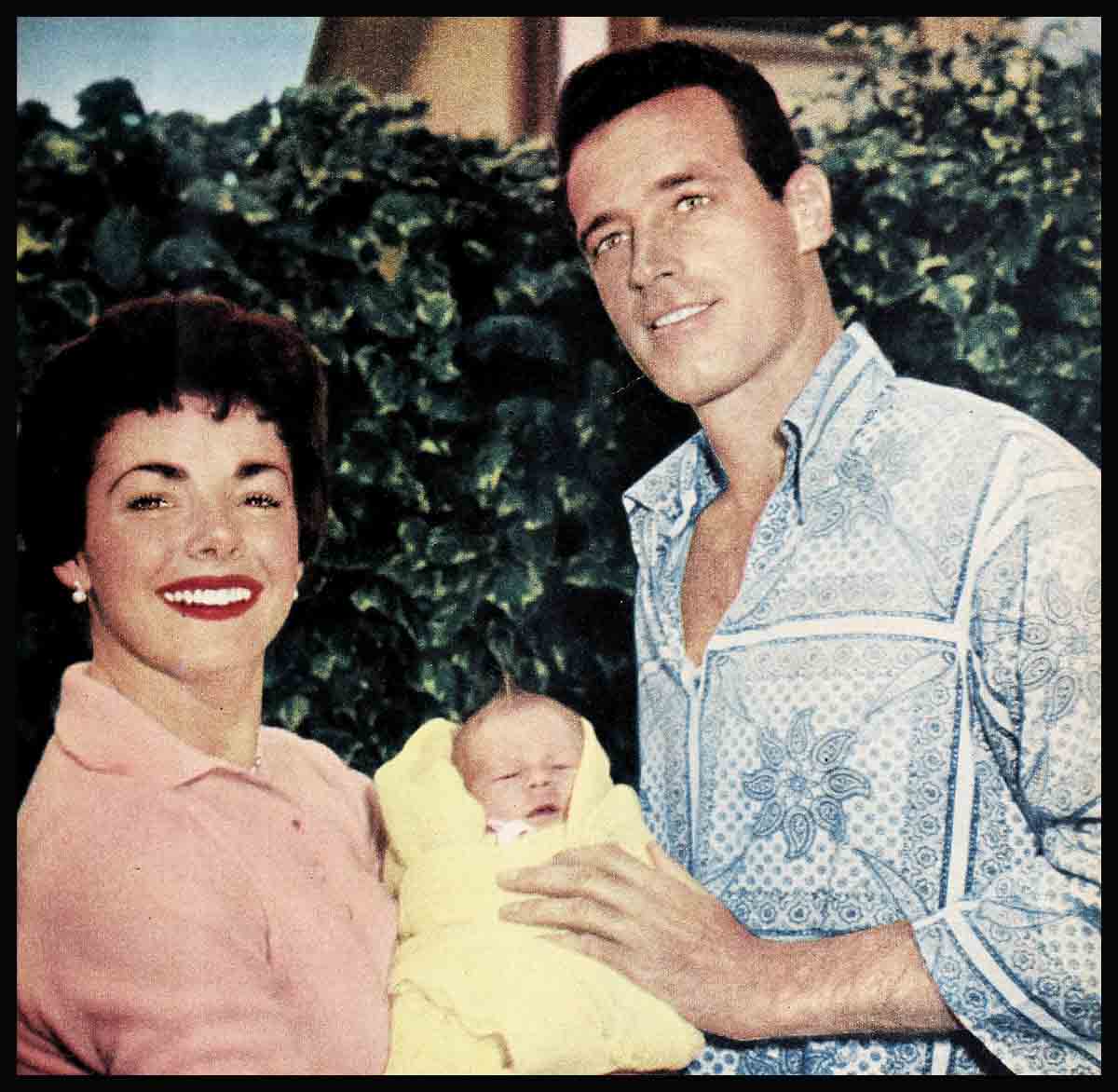

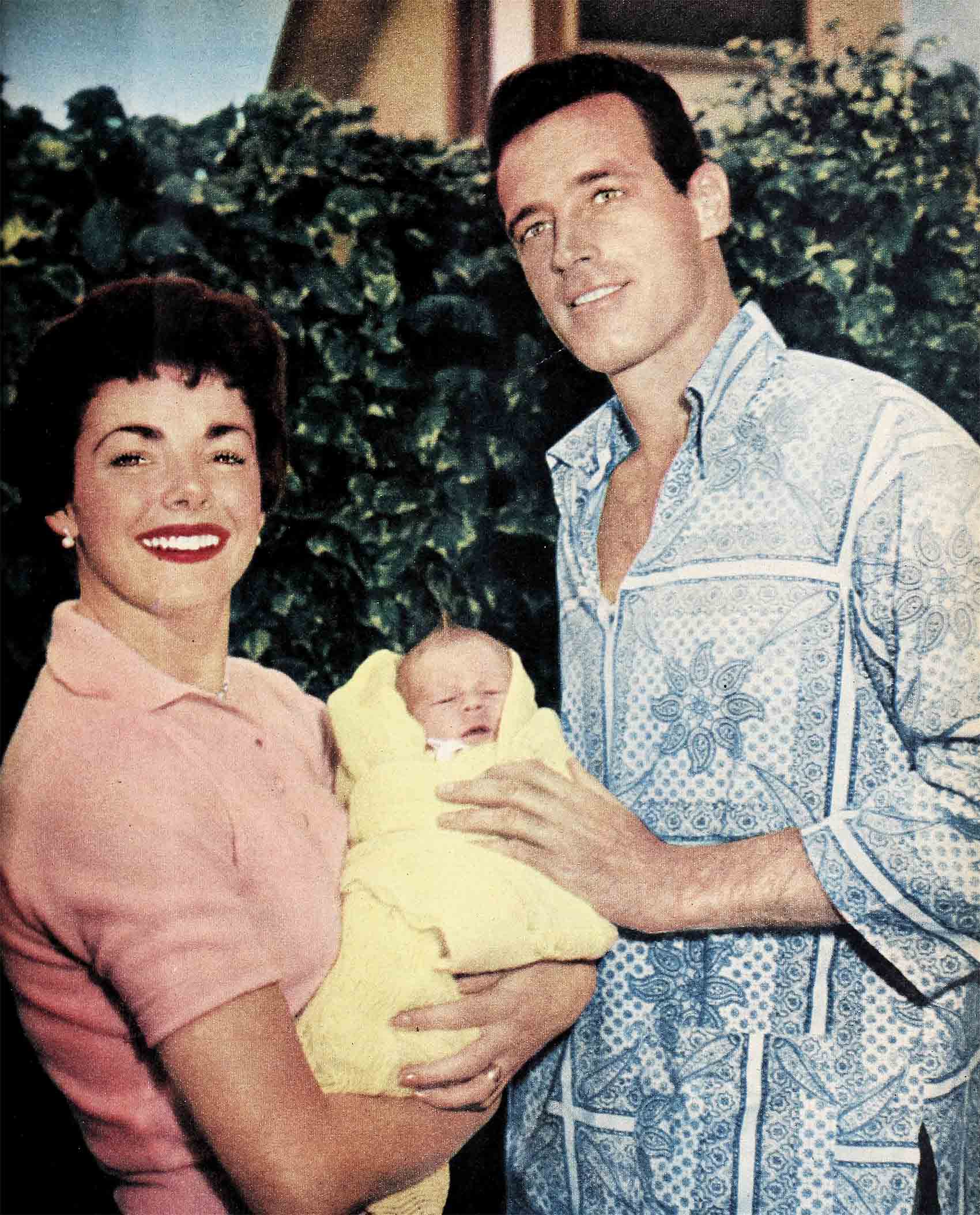

Here in this happy new homestead high in the Outpost section of the Hollywood hills, Wee Belle Hickok fells her father with one flick of a dimple and a cling of her tiny thumb, But he’s quick on the draw—with the camera. Day and night, before he leaves for the studio and after he comes home, he shoots her—preserving every expression, every movement, every day of her life.

As her pretty Irish mother laughs approvingly, “He shoots film on the baby in color and in black and white, when she’s having her bath, when she’s eating her Pablum. And,” she adds softly, “when she’s finding her mouth—her thumb all over her face.”

When Bridget was born, her mother came out of a foggy world early in the A.M. to find a man sitting beside her bed. “I heard somebody say, ‘Look who’s here.’ It was the doctor trying to wake me up. Guy and the baby were both there. The doctor put the baby beside me, but I couldn’t see too well. It was all pretty blurry. I could see Guy just sitting there looking at her.”

He went home and came back loaded down with camera equipment. “He stayed there all day shooting pictures of the baby through the glass. As he explained, ‘She’s more than usual, you know.’ ”

Away from home, her father speaks off-handedly, almost throwing the lines away, “Oh, she looks like anybody’s baby, I imagine. When they’re yours, you think they’re finer, more exceptional,” he begins to warm, then recovers quickly with, “but this can be very boring to others, talking about them.” He says he carries no snapshots of her. “I have some at home,” he adds finally. He has thousands at home. A whole new hacienda full of them. And it’s getting fuller all the time.

Characteristically, it’s as hard as ever for Guy Madison to talk of things close to his heart. As hard as it used to be for a sailor named Bob Moseley who’d grown up a hundred miles over the “Ridge” in Bakersfield and never dreamed of the fabulous future and the fight that awaited him on the other side.

He’s weathered it well. His sun-tanned face is more mature but with that same familiar look, both tender and tough. His keen thickly lashed hazel eyes are wiser now.

But today not only his daughter but life itself are more than usual for Guy Madison. He has a home built of an unusual tawny-colored wood and natural brick. It features a shake roof, a large stone fire- place, the warmth of Early American furnishings and a sunny yellow color throughout. And there is, of course, the gayest, sunniest nursery ever. “Yellow is such a happy color,” sighs Sheila, “and it looks so nice on her.”

Yes, today Guy Madison’s living on top of the world. And his is a setting befitting a man who’s lived so close to the ground. Through sliding glass doors stretch sweeping vistas of greenest hills and bluest skies.

Today Bridget’s father can look down on the future he fought for and is now her own—on yesterday’s defeats as well as today’s triumphs.

Below him are Columbia studios, home of his own independent “Buckshot Productions,” with his loyal fighting agent and discoverer, Helen Ainsworth, as producer and vice president. Farther down Sunset another building houses offices and sound stages for “Wild Bill Hickok Television Productions.” Guy has a percentage of them, and he controls the vast merchandising setup.

In the distance twinkle the lights of Culver City and the old Selznick International studios where, twelve years ago, a surprised sailor in Hollywood on a twenty-four-hour pass was offered a contract and was soon on his way to becoming a famous motion-picture star.

“I feel silly. I can’t act. I’ve never acted. Not even in high school in Bakersfield,” the abashed sailor kept saying over and over again. Agent Helen Ainsworth, thumbing casually through a Navy magazine, had come upon a candid shot of a boy climbing a mast on a ship.

During a furlough he found himself playing a three-minute bit—as a sailor in a scene with Jennifer Jones. The fans took him immediately to heart. Forty-three thousand letters poured in. After his discharge he came back a star in his second picture, “Till the End of Time.”

It wasn’t too easy for Bob Moseley to acclimate himself to this strange and fabulous new life which had come to him right out of the briny blue. But he was sincere, determined and willing to slave away with an army of coaches.

He felt a little out of pasture in some Beverly Hills drawing rooms. He wasn’t hep to the glib chatter and the double-entendre. People in bunches bothered him anyway. But he began boning up like crazy on the arts and literature, on biographies and current events. He kept a dictionary in the back of his old 1939 black Ford coupe and carried it with him everywhere then. “Might as well,” he said simply. If somebody handed him a ten-dollar word, he wanted to be able to give him back his change—and a little more.

But if a few trimmings had escaped him, Guy Madison was well-heeled with life’s more basic ingredients. With character and principle. With respect and devotion for his father, a Bakersfield mechanic, his mother and sister and three brothers. Honesty, truth, sincerity and loyalty he knew. He’d grown up knowing words like these and honoring them.

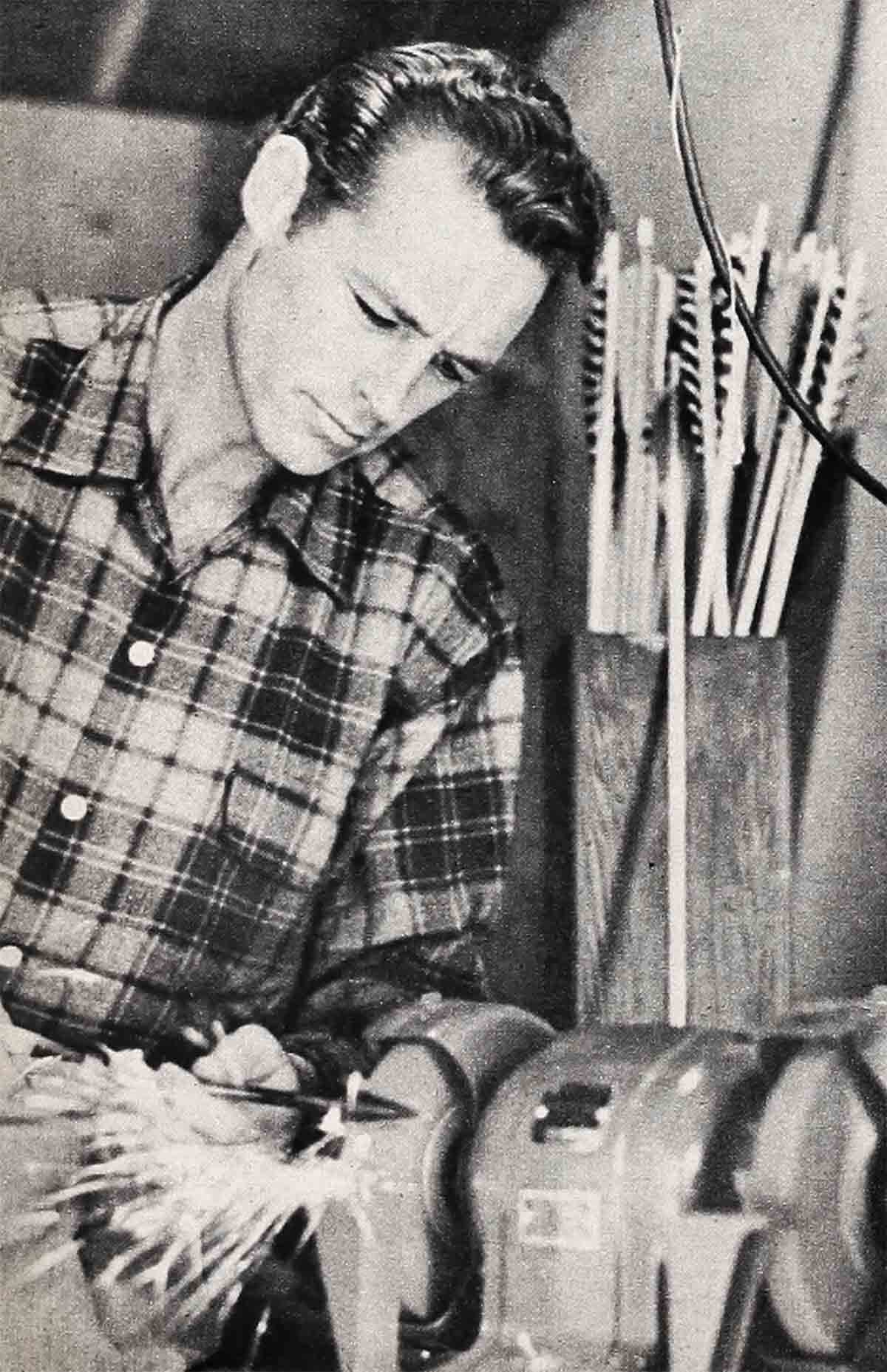

Out-of-doors he was king then, too. He loved to hunt, swim, dive for abalone, and soak up the sun. He was hot with a bow and arrow and he went hunting for wild boar on Catalina Island, often accompanied by a salty dog named Discharge.

In the sun, in action, Guy Madison warmed to his full height. The out-of-doors was his stage. And that’s where an all-but-forgotten Guy came to life again, as “Wild Bill Hickok,” riding across television screens throughout the land and on to the motion-picture screen again. This time to stay.

But today from their own sunlit hill, Bridget’s father can also look down on some defeating days in-between, remembering when his contract was terminated at Selznick International and one executive told his agent pityingly, “Well, you’ve certainly got a dud on your hands. Nothing’s going to happen with him.”

During the years that followed, many Hollywood producers were of the same opinion. Not in the same words, but they all added up to, “Go home, Sailor Boy. You’ve overstayed your leave.” Bakersfield’s Bob Moseley had never asked to be a movie star. Hollywood had invited him. But now he aimed to stay.

Tonight, looking down on those lights that twinkle back at him from Beverly Hills, he well remembers that day five years ago that made this possible. He’d been turned down for another part, and Guy and Helen Ainsworth stood in a parking lot on Camden Drive with one thought, unspoken, “What now?”

Standing there beside her car, the large, calm, authoritative woman said suddenly, almost thinking aloud, “Do you know what?”

“No. What?”

“You’re going to be one of the top Western stars. That’s what you’re going to be!” she said, her voice rising with confidence and enthusiasm.

“You think so, Helen?”

“Yep.”

Today Guy Madison knows many answers that weren’t to be found in any books or dictionaries. But he holds no bitterness for the past. “It’s all part of growing up. I wasn’t hurt too much,” he says.

With today’s success and happiness, Guy can afford to be generous. There’s no room for memories which don’t include the lovely dark-eyed Irish colleen brought so much warmth and love and laughter into Guy Madison’s life today—as well as a daughter who’s so much “more than usual.”

Bridget Catherine, alias Charlie, has a wealth of red hair. “There’s red hair on Sheila’s side of the family and on mine, too,” her father says. And her hair curls “when we dampen it and turn it,” her mother affirms. Her nose? “It’s so turned up—it’s up in the sky.” Each is quick to give all credit to the other. “She doesn’t look a bit like me—look at those dimples. Just like Sheila’s,” Guy tells friends proudly. While her mother’s just as busy being equally fair about the whole thing. “She has your eyes, Guy. Now Guy, she has your eyes.”

She has his eyes, all right, and there’s still the same happy wonderment in them Guy felt when he fell asleep in Sheila’s hospital room and awakened to find himself her father.

“I was pretty exhausted. I’d been in Mexico on location for two pictures, and I’d also been sick. We finished shooting one night and I was on the plane all the next day flying home. The baby was born that night. I stayed awake until midnight.

“I’ll never go through that again,” Guy told a friend grimly. “I’ll never be away from Sheila when she may need me. Nothing could make me go through those last four weeks again.”

They remember how they felt when Guy had to return to Mexico for four weeks’ location for Columbia’s “The Last Frontier” just before their baby arrived. They’re sure Fate must have been watching over them with a very benevolent and maternal eye, for Guy flew in from Mexico on a 5:30 P.M. plane and rushed Sheila to the hospital that same night.

Sheila had insisted on meeting his plane. “When I picked him up at the airport I didn’t feel well and we stopped at the doctor’s office on the way home.” The doctor advised skipping any other immediate plans and going on to the hospital. “But Guy had been away a month and I wanted to talk to him. I had a nice roast cooked for him to come home to and I wanted to have dinner with him at home. I was very ill. I’d have been better off if I hadn’t eaten. I know that now.”

Later that night at the hospital, Guy wanted to stay with her in the labor room. “He stayed as long as he could, but he was so tired he couldn’t keep his eyes open. I got the nurse to give him my room to sleep in.

“Guy’s flowers were the first I saw when I finally came to, yellow roses, about four dozen of them,” Sheila remembers dreamily now. “He gave me a beautiful gold pendant, a calendar disc with her birthday marked with a diamond. Some day I’ll give it to Bridget.”

When Sheila got home from the hospital, Guy told her she should get a whole new wardrobe. And she got it—all gingham! “Guy likes gingham. Not long after we first met, he asked me why I never wore it. So I bought gingham. Shorts, sports dresses, afternoon dresses—everything.” Guy came home from the studio one night to find both of the women in his life attired from stem to stern in gingham. “I even got gingham checkered diapers for the baby,” she laughs.

With his customary serious application, Guy takes fatherhood more than usual. At the hospital when Bridget was first born, Guy worried because he never heard her cry. “Are you sure she has vocal chords?” he would say anxiously. Until finally the doctor snapped her bottle and she yelled. “Oh yes, she can cry,” he assured Guy calmly. Of this, Guy soon had no cause for doubt. Then he worried because she did.

One day the nurse was trying to teach the baby to roll over by herself. “She’ll be crawling before you know it,” the nurse observed proudly to Bridget’s dad. “Yes, I hope you’re training her,” he said earnestly. “Guy thinks she has to be trained to do everything,” her mother laughs. And he’s beginning to suspect the same holds true for her dad.

On the nurse’s first Sunday off, Guy and Sheila were taking care of the baby and having a ball. Guy went to the kitchen to fix her Pablum, and Sheila could hear her husband rattling dishes around. “It’s in a cup on the shelf,” she called. “Guy came back with a dish of something mealy that looked like Pablum, but the baby cried and wouldn’t eat it. I kept trying to make her,” she recalls now with a wince. Finally she asked Guy, “Are you sure that was Pablum?”

“I’ll go back and look,” he said.

It wasn’t. He’d mixed whole-wheat flour with her formula. Sheila was aghast. “And I forced it down her!” she said. Guy was on the phone calling the pediatrician in nothing flat, with Sheila prompting, “You’d better tell him you did it—I don’t want him to think I did it.

“Fortunately the pediatrician assured us no harm was done.

“I think her father’s going to turn the baby into a tomboy,” her mother muses fondly. “She’s going to ride and swim and shoot. And we’re taking her on a wild boar hunt on Catalina,” says Guy’s piquant-faced bride, who’s as wholesome and rugged as she is gay and glamorous. “Guy’s made me a dozen of the most beautiful arrows you’ve ever seen,” boasts Sheila, who’s as misty-eyed about arrows as other women are about mink.

For all today’s happiness, Bridget’s father is still a man of relatively few words, even fewer where those he loves so much are concerned. Mention Sheila’s a doll and you get a rare quick smile. “That’s why I married her.” Ask what he loves most about her, and he says quietly—and decisively—“If you love somebody, you love everything about her.”

You can take Sheila’s word for this, too. “He’s exactly the man I was looking for—in every way,” she says. As for what she most admires about him, “I think his patience and understanding with people. I’ve never heard him say anything bad about anybody. He can always find some excuse for them. I don’t think Guy’s ever done a wrong thing in his life,” she adds slowly. Her career? “I never miss a career—and Guy says he has my career all mapped out for me.”

Sheila suspects, with some degree of reason, that the stage he’s mapped out may be their new kitchen. “It has a lovely view, and when we started planning the house, my husband said, ‘You’re going to spend a lot of time there—we might as well get what you like.” Nothing was too good for their kitchen. There’s a beamed ceiling, a lush copper stove, a glamorous yellow refrigerator and other yellow appliances. A kitchen guaranteed to inspire and bring out the creative, except, say, when it comes to cooking corn bread.

“I’d never even heard of corn bread before I met Guy. And he doesn’t like the ready-mixed kind. I have to make it myself, and Guy taught me how. But every time I make it differently. Either lighter or darker. Once, in a big hurry, I used the ready-mixed and guy said it was the best corn bread he’s ever tasted, but he doesn’t like it,’ she says smiling.

A wealthy girl, Charlie. From her mother, she has beauty and wit and tenderness. From her father, spirit, sincerity and the strength to live up to the legacy he’s homesteaded for her. She will have all the answers her father’s found. Those that weren’t in the dictionary he used to carry in the back of his old beat-up car.

The girl he calls Charlie will be exposed to her father’s own wholesome evaluation of life. Guy always believed in discriminating between people only as individuals. He picked his people one by one for what was inside them.

Nobody would know better than her father how cruel other discriminations and snobbish behavior can be. Back in Bakersfield, a hub for many migratory workers, Bob Moseley was never part of the town’s leading clique. “The head ones,” as he used to explain. “If you didn’t have a car or good clothes or wouldn’t take a drink, you weren’t in.” Not that this particularly bothered him.

Nor did he worry too much about whether or not Hollywood would accept him socially later on. The way he sized this up, there really couldn’t be too many legitimate cliques in Hollywood. “It would be hard to have them here. Some people might like to, but they can’t very well. They don’t know who’s going to make out, or whether they themselves will continue making out. They don’t know who’s going to be in, up, down or out.”

Nor did Guy know whether or not he would “make out” in Hollywood then. He admitted he would rather be a movie star than anything, and he’d work like fury to get there. “It’s a mighty fine business and I like it. It would be hard to leave. There’s more money in it than anything else, too. That’s what scares a few of the people who come here, I think. They get scared they may not make good here, or they feel themselves slipping, and once in a while they do things they otherwise wouldn’t do in order to stay. But I’d never be confined to doing something I don’t want to do, something I don’t believe, because of any job.”

Guy Madison made out fine—and on his own terms.

It seemed inevitable that Bridget’s father would become a spokesman for clean sportsmanship on the screen, that he would achieve his own fame championing justice and honor and truth, and that he would be among those who inspire today’s youth.

“This is only one man’s thought, of course, but I think you can give people good clean entertainment in good outdoor action pictures and help more than in pictures with a message,” he says seriously now.

With a daughter of his own, he holds youth and its problems and its future even closer to heart today, and with his own affinity for the out-of-doors, Guy’s already planning the ranch he’ll have when she’s older. In his opinion, any star’s children are better away from the limelight during the more impressionable years. “I think it’s better to raise them away from Hollywood—at least part of the time. Some day we’ll have a ranch not too far away from here and we’ll spend as much time there as we can.”

His own future? “Someday I want to direct.” Meanwhile, he just wants to “go on having a home, raising a family, working hard and trying to make enough money to be sure I have security for them.” There’s a little redhead in that future now—a little redhead who’s more than usual, you know—and her father’s plans surround her.

For all his own experiences since he’s been in Hollywood, ask Guy if Bridget will follow the same profession, and he says in a tone which leaves small doubt. “She will if she wants to.” Her father and her own red hair will see to that.

As for his own long hard pull, he says, “I feel I’ve been very lucky.”

Lucky—to be able to put a future in a little girl’s hands. Lucky to be able to give her advantages and make life easier for her than was ever his own. Lucky there’s a Mrs. Sheila Madison.

Through unhappier years and the long hard pull, Guy was led onward and upward by his own deep unshakable faith that told him it all had to lead somewhere.

“I’d hate to think you could spend twelve years working for nothing. Not have something to show for it. It had to be for something. Lead somewhere.”

It led to the top of a hill and to all the happiness there for a more-than-usual man.

THE END

—MAXINE ARNOLD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1955