Search For Faith

OUTSIDE THE JAPANESE orphanage a heavy-set young man wearing dark-rimmed glasses sprawled on the green spring grass and sang gay songs for the little children who crowded around him. They were simple old-fashioned songs like “Old Black Joe” and “Oh, Susanna.” The Japanese orphans, charmed by the American stranger, spiritedly applauded after each number, shouting “Hallo,” the only English word they knew, to show their appreciation. The singer was Marlon Brando, who was in Japan making “Sayonara.” The day the picture was completed he had asked one of the Japanese players to take him to an orphanage that he had visited the year before when filming “Teahouse of the August Moon.” It had been built around an old Buddhist temple. Marlon, who had filled up the back of his car with flowers and candy, watched the children in their classrooms. When they were let out to play he romped with them on the orphanage grounds. He tossed them up in the air, carried them around piggyback and then, after the last of the candy had disappeared, sang to them in a quavering tenor.

AUDIO BOOK

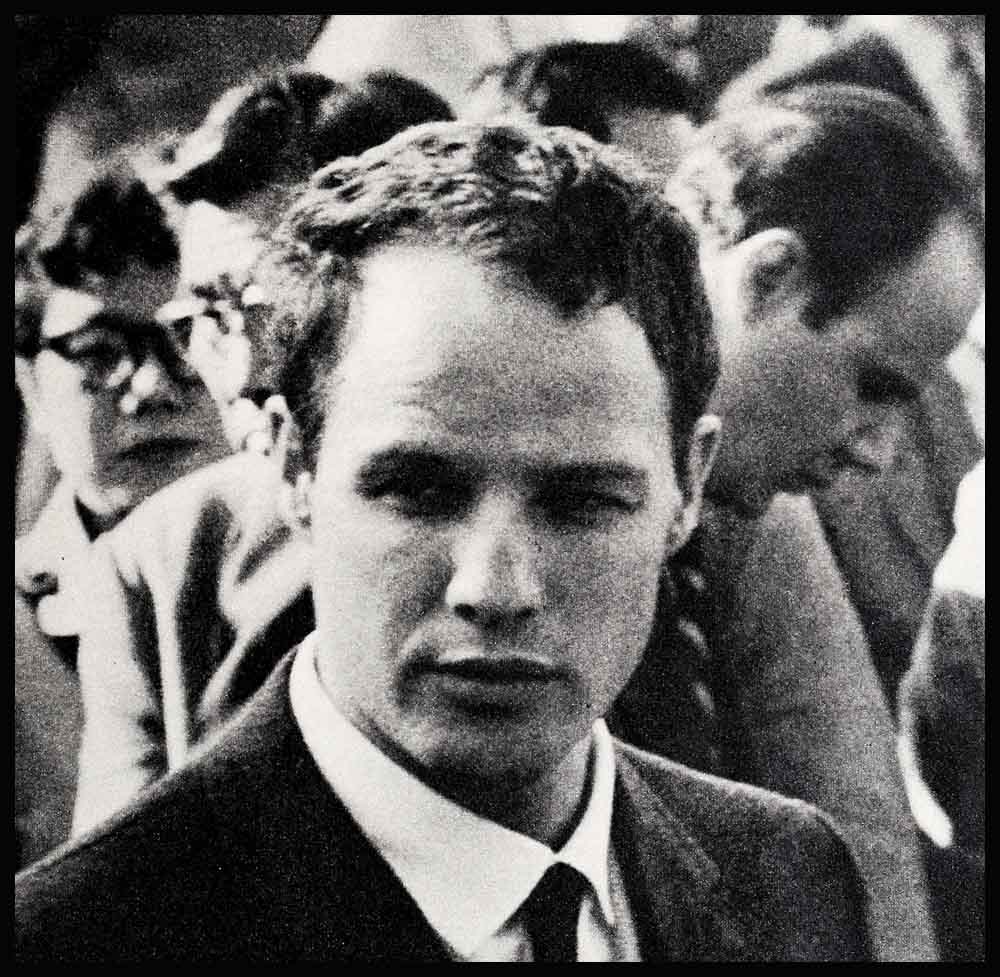

This was a strangely different Brando than anybody had seen before. Happy and relaxed, there was a kind of tenderness about him that made the bongo-playing, T-shirt, motorcycle-riding days seem as remote from his new personality as the tiny orphanage was from Hollywood.

Perhaps it is because for the first time in a long time Marlon finds himself in an environment where he can be himself, and be accepted. Marlon makes it clear that he likes and respects the Japanese people—and they, in turn, like and respect him.

Some of the stories coming back from Japan are tender and moving. M-G-M called a party for the Japanese press, and Marlon, who used to feel so uncomfortable and unacceptable that he felt he had to prove he didn’t care at all by being rebellious and offensive, was content to sit quietly in a corner the entire evening. “He’s even shyer than Japanese,” said one of the Japanese newspapermen in wonder, and they liked him for it.

He’s a little bit in wonder about Asians too. “They stand at a distance . . . they don’t bother you,” he says, almost in awe. “I went into a Hong Kong store to buy something, and a lot of people started peering through the window. By the time I came out there was a big crowd, but no one pushed at me, or asked for autographs. They quietly parted and made a path for me to walk through.”

There are heart-warming episodes. But there are others too, both confusing and disturbing. There is the report that Marlon has lost his fervor for acting, that he has turned writer, he’s hard at work on, and has almost completed, the psychological Western he’s been writing called “Burst of Vermilion,” which he intends to produce and direct, as well as act in, for his own Pennebaker Productions. And then there were other reports. That Marlon has become interested in Buddhism, Marlon has re-discovered religion. Recently, newspapers carried a story that Marlon was going to give up acting. Another alluded that he wanted to go into the ministry.

And there, far away from where the gentleman in question can answer these reports himself, he’s stirred up a tempest of claims and counterclaims. His fans worry. “Doesn’t he care about movies any more? Why has he been away so long?” “I know he said he wanted to do ‘Teahouse of the August Moon’ ” wrote one fan, “to promote a better understanding —but now he’s doing ‘Sayonara’ abroad too, and there’s talk he’ll make still another picture m Japan. That’s being away from home too long! People forget. As it is, even now Marlon’s appeal seems to be fading. He isn’t on the popularity polls anymore (he used to be close to the top) and the magazines don’t write about him anywhere near as often as they used to. What’s happened to the guy? Where is the old Marlon Brando of ‘Waterfront’?”

Frankly, these questions worried many people, for despite the fact that he’s achieved stardom and almost achieved marriage, Marlon’s never managed to find any real joy or happiness or contentment.

When he was in his early twenties, he tried his luck on the Broadway stage— where actors have been known to starve for years between odd jobs and walk-on parts before they got a big break—yet Marlon made stardom with his second play, the electric “Streetcar Named Desire.” To old timers, it seemed like a short cut to heaven, but it let him restless, and when a chance to make movies came along, he grabbed at it.

But a movie career gave him little joy, either. He fought with everyone, and time and again threatened to leave Hollywood. “Movies aren’t an art,” he shouted to all who would listen. “They’re big business. And if an actor regards it as anything else, he’s a dreamer.”

Misunderstood, almost ostracized by Hollywood socially, he fought for roles that would give him a chance to be an actor of variety and depth, and stories that were strong, real and honest.

The vigor of his Mark Antony in “Julius Caesar” surprised the critics, and when “The Egyptian” was on the studio schedule, he shocked the studio—and everyone else—by walking off the set. “Who,” he muttered, “could compete with 50,000 camels?” Elia Kazan, and a good script, got him on the screen in “On the Waterfront,” and his judgment seemed vindicated. He kissed and made up with 20th Century-Fox, and made “Desiree” for them.

And then he softened, and that was the year of The Big Change—the year after his mother’s tragic death. He traded in his blue jeans, trotted out a tuxedo for formal occasions and a homburg for informal ones, dressed the way people expected him to and acted the way they wanted him to. He’d even gotten himself engaged to Josanne Berenger and won himself an Oscar for “Waterfront.” It looked as though Marlon had found fame and respectability and love—and that he liked it.

He treated his role in “Guys and Dolls” lightly, talked about “not having to be perfection, just doing a good day’s work,” and started his own Pennebaker Productions with intentions of producing a Western, “To Tame a Land.” It looked as though money was what he wanted, and money was what he intended to get.

And yet, just a little while later, he went off in still another direction. His thoughts crystallized, his plans emerged, and he asked to do “Teahouse of the August Moon” “to help bring East and West together,” then made a trip through Asia in preparation for doing his own “Tiger on a Kite,” a story for the United Nations, before he started work.

Then, last summer, he put his closest feelings into words when he told a reporter, “By now I’ve made enough money to live comfortably the rest of my life, so my main concern is not with making money,” he said. And then he sobered, and said the words as though he were taking an oath, “I would like to make a cultural contribution and help some of the big social problems of our day.”

Later, he told another reporter, “The Asians are looking to us for signs of friendship. You have no idea of the harm an unsympathetic picture can do.” Then he added, “Only by international brotherhood of man will the world survive.” It was the kind of statement that might have sounded pedantic, yet when Marlon said it, it emerged as a personal philosophy.

To those who were watching and observing him closely, it was an electrifying statement. Here was a man who could fight for the underdog, who could do good things when he was acting (as Mark Antony in “Julius Caesar,” as Terry Malloy in “On the Waterfront”) but who’d never had the courage before this to say that he wanted to reach out directly to people. Now he was ready to do it.

From Japan, the reports of his kindnesses, his sympathies, his wanting to do good, generous things came as something of a shock. Yet they needn’t have. Basic ally, he’s been that sort of person underneath, yet he seems to have worked overtime to hide it from the world.

A close friend of his relates that when Marlon came home from Shattuck Military Academy he told his father that he wanted to be a minister, because he felt that some day he would have something to say.

His father studied him closely and said, “You can reach out to people in an audience too—and you can teach them something.” That’s when Marlon decided he wanted to be an actor.

And, if you were looking for the signs, you could have seen them in his childhood, when he begged a friend not to step on some ants in his presence “because they have a right to live too,” and in his early days in Hollywood, when he shocked a few people by showing disdain for a top-notch producer because he had animal trophies in his office. “All those slaughtered animals!” he’s supposed to have said with a shudder, when someone asked Marlon how he liked the producer.

There were other signs too: He paid for a year’s worth of visits to a psychiatrist when a friend’s wife was having her emotional troubles, and he agreed to do Ed Murrow’s “Person to Person” because, as he put it, “Mr. Murrow is making a contribution.”

There were signs then that Marlon was coming out of his shell, but only now is it clear that he isn’t afraid of being the kind, gentle person he always was, potentially. Instead of hiding behind the face and voice of the character he’s portraying, he isn’t ashamed to show himself as the kind of person he’d like to be. Screen writer Louis L’Amour, a friend, says, “Marlon is still growing. He still has his best work to do. He hasn’t come more than half way as far as he can go, and will go.”

This was partly responsible for his break with Josanne Berenger. “Josanne,” he once said succinctly, “still has some growing up to do.” He might have added that he himself did too—and that they were growing in different directions. He might have said it, but he didn’t need to. It was something he felt.

A career, love, peace of mind—these are the things that Marlon is fighting for. Today at times he acts like a man who is fighting for his soul and his conscience. all his life he’s acted as if to be shy and gentle were something to be ashamed of. Now he’s less afraid to reveal this side of his nature. The steps toward maturity have been slow and painful for Marlon, but he has come a long way. As one of his friends put it, “Marlon has recently discovered that living is more important than anything else. I think that if acting ever became an obsession instead of an occupation or a means of expression, if it ever became more important than love or friendship, he’d give it all up. His search for faith goes on. Some day, he’ll find it, and himself—and I think he’ll find happiness when that day comes, too.”

THE END

DON’T FAIL TO SEE: Marlon Brando in Warner Brothers’ “Sayonara.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1957

AUDIO BOOK