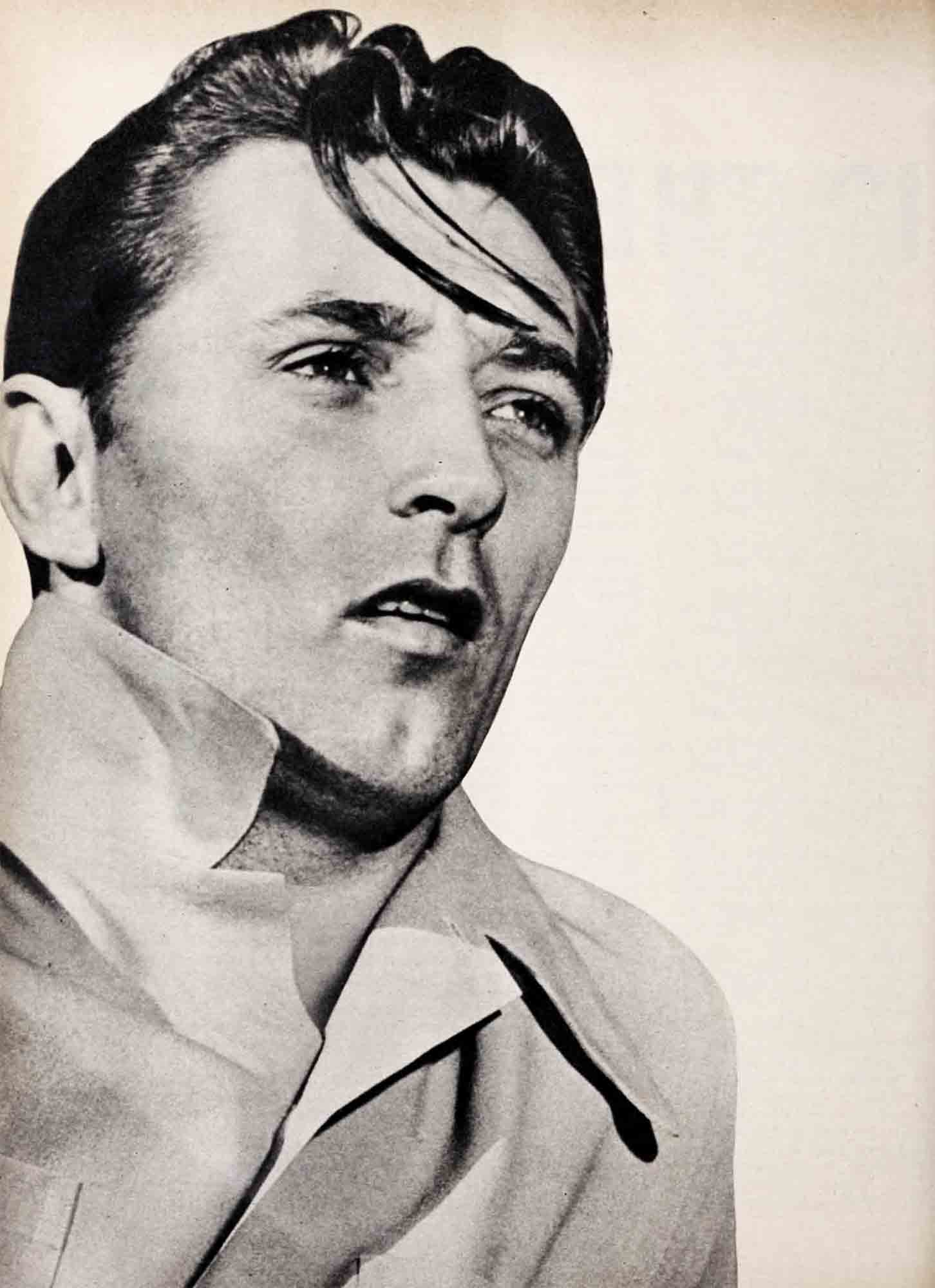

Why Can’t Robert Mitchum Behave?

Bob Mitchum has gone and done it again—made himself a raft of new headlines that have tongues clucking and brows wrinkling. And the sad thing about it all is that Bob, somehow, just couldn’t help himself.

It is perhaps one of his major misfortunes that he resents officialdom with,a furious resentment—an antipathy that goes back to his boyhood, when at the age of sixteen, he was cruelly tossed into the horrors of a Georgia chain gang merely for the sin of being broke and hungry. From babyhood on, he has resisted authority; rightly or wrongly, he has fought to be the opposite of a “yes man.” He is unable to tolerate even the slightest pushing around or the simplest questioning of his motives.

AUDIO BOOK

“Bob,” says Dorothy, his wife, sadly, “has the rugged independence of an Army mule.”

Unluckily for Mitch, this facet of his character is inescapably mixed with a compulsion to have everyone like him. The result is a curious compound of orneriness and over-amiability. He seems forever torn by impulses to go overboard in one direction or another. “Poor Bob,” a close friend once remarked, “he has always fought against hurting himself, his family and those he loves; but sometimes he seems unable to help himself. Something perverse—some demon—always seems to be nudging him. He is one of those tragic men born to be their own worst enemies.”

Certainly Bob’s unpredictable antics baffle and sadden his friends. Those who know him only slightly dislike him intensely; those who know him well have an affection for him that comes close to adoration. They respect his intellect, admire His humor and humanity and feel a little awed by his rare sympathy for the little guy. Yet, even those fondest of him know there are times when Bob, driven by deep, subconscious guilt feelings, acts like a raging child banging his head against a wall, inflicting pain on himself-—but paining his friends and family even more.

Bob’s last escapade shocked intimates, and even his most devoted friends agree that it was curious behavior. What happened was that Officer J. N. Ryan, patrolling L.A.’s Wilshire Boulevard, saw Mitch whip his black Jaguar speedster around a right turn and “race along like a grasshopper, doing better than seventy miles an hour.” When Bob finally was flagged down, a few miles farther on, he got out of the car (he had not been drinking) and handed the policeman his keys.

“What are they for?” asked the mystified officer.

“Maybe my driver’s license is in the trunk,” Bob deadpanned.

Mitch, however, finally produced his driver’s license from his wallet, then asked, “What have I done?”

“You were doing seventy-four.”

The police officer proceeded to fill out a citation, but when he asked Bob for his correct address, the actor reportedly replied, “I don’t have to tell you.”

Then suddenly, while the officer was still writing the citation, Mitch got into his car and roared away. When Ryan, unable to catch Bob again, returned to the West Los Angeles police station, he found Officer David Sellers on the phone. “It’s Mitchum,” said Sellers. “He claims some officer stole his driver’s license.”

Ryan, according to the newspaper accounts, then took up the conversation, and asked Mitchum why he had driven off. “I didn’t know who you were, Dad,” he quoted Mitchum. “I thought you were a bandit or something, so I went home.”

Other stories stated that Mitchum also asked the officer, “You got a witness, bub?” And when the policeman said “No,” Bob reputedly grinned and quipped, “Well, neither have I. See you in court.”

At 3:00 a.m. when reporters swooped down on Bob’s house in Mandeville Canyon, they found Dorothy home but Mitch gone—“out with a friend,” according to the patently distressed Mrs. Mitchum. The next day Mitchum was face to face with a possible five years, six months and five days in jail and $5,500 in fines, based on a triple complaint issued by the Deputy City Attorney’s office. The charge was escape from lawful custody, resisting, obstructing and delaying an officer in performance of his duty, and doing seventy miles an hour in a thirty-five-mile zone.

Fortunately for Bob, his wife and youngsters, the judge before whom he appeared a few days later, let him off with only a $200 fine, but castigated him severely for doing “an extremely silly thing.”

“Yes, Your Honor,” Bob admitted, now thoroughly subdued, “it was a silly thing to do. I’m sorry.”

It must be said for Bob that he took his notoriety and punishment without a murmur, paid his fine and went on his way without shrieking, “I was framed.” His home studio, RKO, could have provided Bob with a mighty battery of high-priced legal eagles to defend him. But Bob thanked them politely and declined all aid.

“I’ll handle this myself,” he said. “If I sound like a fool, I am, but I’m my own fool. Nobody else’s.”

It is a curious character trait of Bob’s that when faced with a tough situation, he cannot deal with it soberly and with gravity on the spot. “I hide my feelings if I’m panic-stricken,” he admits. “I get a tendency to crack wise.”

This strange compulsion could also account for the fact that he seems to take a satanic pleasure in shocking people—in deliberately spraying the air with lurid, smokehouse language when the most correct matrons are around. His favorite remark when he finds himself in stuffy company is, “Well, when I was on a Georgia chain gang . . .”

There are those who think that, deep down, Mitch actually hates himself for real or fancied inadequacies—that in his inner self he seeks his own destruction. How else explain the Mitchum explosions that periodically lead to headlines?

Not long after Bob had returned from the Canada location for “River of No Return,” for which he had been loaned out to Twentieth, he had a late call to shoot some night scenes. He had dinner and returned to his dressing room to glance over his script while the lights were being readied. On an impulse, he decided to make an outside telephone call. Reports of the incident vary, but the story is that an inexperienced night operator either failed to identify him or felt she could not make the connection without front-office approval. (There was a studio economy wave on.) At any rate, Mitch became enraged at the supposed affront, grasped the phone and yanked it from the wall.

The following day, when all the gossip columns buzzed with the incident (some extra girl on the set had leaked the story), Bob again tried to solve a tough situation with a wise crack. Publicly, that is. But deep inside he must have been humiliated by his outburst. As he once confessed, “I always manage to put my foot into it one way or another. This isn’t my intent. It’s just the way it works out.”

Only recently, Bob added another to his long string of skirmishes with Howard Hughes, who owns his contract, when he declined to appear in “Susan Slept Here.”

This time, however, reason seemed to be on his side. “It was a good, cute script,” Bob told intimates, “and that little Debbie Reynolds, who was to co-star, is really a doll. But the picture is a musical, and I was supposed to sing and dance in it. ‘It’s a great switch for you,’ the high brass told me. ‘You’ll fracture ’em.’ But that was just what I was afraid of. I’m not a singer and I’m not a dancer. Sure, some day I’d love to do a musical, but not yet. I’m not ready—not nearly ready.”

When Mitch told the Big Wheels more or less the same thing, and suggested that they pretend they had never even heard of him, there was a flurry and scurry and clamping of executive jaws. In no time at all Bob was on suspension. Furthermore, his $5,000 a week salary was cut off.

Some people who didn’t know Mitch well sneered at him for daring to flip away that kind of money in these uncertain times, and merely for the sake of a silly principle. But what they didn’t realize is, that’s the way the guy is made: rebellious at heart, a game fish who has always swum against the stream.

The trouble with Mitch—one of the troubles, anyway—is that he not only hates stuffed shirts, but lets them know about it. Now there are stuffed shirts and stuffed shirts, and there are some in Hollywood whom you are not supposed to unstuff—not in public nor in print, anyway. But Mitch does, rudely and with great glee. “People,” he says, “are always telling me, ‘Watch it, boy. Play it safe. Be careful.’ But that chokes me off. What for? Being careful’s not living—that’s for the cemetery.

“If I ever get out of pictures,” he once said, “I’ll open a factory making fancy celluloid buttons marked ‘Genius.’ I’ll bet I sell one to every producer in town.”

During his early struggling days, he worked for awhile as a shoe salesman to help pay the rent and milk bills. The money wasn’t much, but it was needed—desperately. Yet that job ended suddenly when Bob informed a hard-to-please customer that he had a foot like a cigar box and that the store just didn’t stock any six-toed shoes.

Another time, and later, Bob was called in to discuss a picture contract with very important executive who thought Mitch, with his Indian face and 180 pounds of rogue male appeal, had possibilities as a leading man. “The first thing to do, of curse, said the executive, “is to change your name. We’ll make it Robert Mitchell.”

Robert, who then had two kids, a wife, one pair of pants and a little less than a dollar to his name, uncurled his big frame from the chair and stood up. “Which way is the door?” he asked.

The name remained Robert Mitchum, because the executive was a nice guy, and didn’t care to make an issue of a minor point. Yet Bob’s stubbornness could have cost him that job.

Too often, though, Bob’s continual search for the right answer has led him into paths that wound up leaving him no-where. Some of the endings have been tragic; some have been childish.

It has been said of Mitch that such time as he can spare from sleepy-eyed stardom, he cynically devotes to the neglect of his character. Part of the pattern of his self-destruction is deliberately to destroy your good opinion of him. Ask him what he does to keep in trim and he will, as likely as not, inform you, “Well, I carry out the garbage once a week.” Inquire if he is a basically happy person and his answer is, “Every Thursday when I pick up my pay check, yes.”

What Bob says is constantly filled with overtones of sardonic wit, as most of those who come in contact with him know. It is a kind of unhappy whistling in the dark—a deep desire to cover up a very real helplessness. People who hide behind such macabre humor are forever appearing to shatter respect for institutions and truths in which they really believe very deeply.

Bob’s tendency towards lurid self-dramatization is another aspect of his deep-seated disbelief in himself as Robert Mitchum, human being. Once, in speaking of the troubles he has caused his wife, he called himself “a comic strip character who is glued to his background by printter’s ink. It is Dorothy’s misfortune,” he went on, “to have reared a monster.”

His sister Julie still remembers when Bob, at the age of twelve, accidentally shot his best friend in the hip when a shotgun went off in his hands. Bob was sick with remorse and threw the gun away with loathing; he didn’t use a gun again for years. But even then he dramatized the incident, He came home and told his mother that he had finally done what everyone had prophesied he would do: he had shot a man; he was a criminal!

When Mitch makes headlines, his friends and family are abashed and saddened. Those who know him feel that it is a great pity so talented a human being, with such great potentialities, should prove himself his own worst enemy by his actions. His attitude towards his work is professional; his story sense is sharp and accurate and many a script on which he has worked has benefited greatly by his suggestions. His humor, too, is fresh, original and rib-tickling.

People who worked with him on “River of No Return” fondly remember the day when Mitch, riding a fierce-looking range pony, was supposed to amble up the main street of a tiny frontier town and dismount. Five times he repeated the action, and till director Otto Preminger just wasn’t satisfied.

But finally, the sixth time around, all went well. After Preminger yelled, “Print it Bob wiped his brow in relief. “Some day,” he drawled, “I’d like to make a modern Western where the cowboy comes into town—driving a Cadillac”

Among Mitch’s thousands of fans, none is more enthusiastic or loyal than a recent convert named Marilyn Monroe. Having worked with Bob and seen his patience and understanding and unselfishness on the rugged “River of No Return” location—Bob and Marilyn almost lost their lives on a log raft in swiftly boiling rapids—she told everyone, “Mitch is one of the most interesting, fascinating men I have ever known. He’s a hard worker, who rarely misses a line, or cue or a bit of business. I was worried about the picture, but he helped me gain the confidence I needed. He was free with his time, his energy—with everything he had. When I hurt my leg on location, no one was more concerned about my welfare than Bob. He gave you the feeling that, if you needed it, you could have the shirt off his back.”

Not long ago, it was Mitch who “agented” the very capable Dick Egan into the lead opposite Jane Russell in “The Big Rainbow.” Dick is an extremely capable young actor who had so far lacked the big break. Bob not only went to his good friend Jane and told her, “You’ve got to get this guy,” but even persuaded producer Edmund Grainger to catch Egan’s last picture. Bob got nothing out of this other than the satisfaction of boosting a fellow player.

Despite all his reputed quarrels with his wife, he is deeply in love and would be miserable and lost without her. She is the only girl he has consistently been interested in since the age of sixteen. He idolizes his two boys, Jim and Chris, and his baby daughter, Petrine.

One day, during the filming of “River of No Return,” Mitch stood on a raft in a process shot in turbulent waters, while four special effects men on catwalks overhead shot lethal steel-headed arrows literally between his legs. These arrows hit the solid oak planks of the raft so hard they had to be pried out with heavy pinchers. The Indian attack on the raft went on for six or seven takes, with Bob standing on the shaky craft’s huge wooden sweep and crooning softly to himself. The man seemed nerveless, devoid of emotion.

Yet a few minutes after the scene was wrapped up, Mitch was over in his trailer dressing room dangling little Petrine on his knee (Dorothy had brought her over for a visit), feeding the tot a cup of milk with amazing tenderness, and then parading around the cavernous sound stage with the baby perched high on his shoulder. He was also gruffly solicitous of little Tommy Rettig, the boy in the picture.

But the gnawing, dissatisfied restlessness somehow remains—and probably always will. Bob’s wife says that he is really a bachelor at heart and the most married bachelor in town. “Mitch,” a director who has worked with him says, “is an actor who loves acting, yet feels that acting is a humiliating thing for a grown man. That makes him deeply unhappy. I really believe that he would rather be a writer or a director—and as a director, I think he could do a terrific job. But since they won’t let him do what he really wants, he rebels—and then he gets into trouble.”

Is Bob, then, really his own worst enemy? There are many who think he is—this gruff, seemingly cynical, idol-smashing character who all too often inspires such a curious mixture of deep affection and intense exasperation. “I love the guy,” a fellow worker confessed, “but, doggone it, these grey hairs and this ulcer I have were given me by him.”

So, as Mitch chuckles, “Go fight city hall.” All in the same day you have to admire him, pity him, laugh with him and sorrow over him. Once he said, “Oh, well, we tramps have our own little world.” Someday he’ll find that little world isn’t quite enough. Until then he’s Mitch—a man like nobody else.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1954

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments