James Cagney: “If You Want To Be Somebody”

There was a time, not too far back, when opportunity was believed to knock on every door, success depended upon whether you were there to answer it back. If you wanted to be a movie star, just sit long enough in a Hollywood drugstore, sipping a soda. A talent scout would ultimately come by, discover you and change your name from Jean Turner to Lana. You’d be famous in a matter of weeks.

Then times changed. Don’t go to Hollywood, everyone warned. Wait until Hollywood comes to you. And while you’re waiting, better learn how to act. Breaking into pictures these days takes more than looks, more than personality. So, all over the country, young hopefuls enrolled in schools and colleges. After all, Marlon Brando, James Dean and Eva Marie Saint had studied at the Actors Studio in New York. Charlton Heston had gone to Northwestern. So had Ralph Meeker, Jean Hagen and Patricia Neal.

But now, suddenly, times had changed again. When the big studios reduced the number of actors on their contract lists, they stopped scouring the campuses for new faces. Nowadays, you could act your heart out in college plays, but no talent scout would catch your performance. Hollywood was no longer coming to you—not unless you had a name.

Last spring, however, Hollywood did come to one campus—in the person of James Cagney, who was invited to Rollins to receive an honorary degree. The College was making him a Doctor of Humanities—Jimmy Cagney, who had once pushed a grapefruit into his leading lady’s face! But the Public Enemy of the Thirties had grown into the Yankee Doodle Dandy of the Forties, and now, in the Fifties, was hailed as one of Hollywood’s greats.

To fifty-some students in the Drama Department, it was the chance of a lifetime. If anyone could give them the real low-down on Hollywood, it was Jimmy. He had been there in the old days, and he was still there—still a star. What’s more, he was also a producer and a former president of the Screen Actors Guild. But best of all, he had promised he’d sit down with them and try to answer all questions. How he had broken into pictures and how could they do it today? What were their own chances of ever becoming stars?

He was celebrating his twenty-fifth year in motion pictures and the completion of his fiftieth film, but the man who arrived on the campus at Winter Park, Florida, was still young. His hair was still red. His step was springy enough to make professors vow they’d start exercising in the college gym—first thing tomorrow. And you had to search his face for a line or wrinkle under that mass of freckles.

Jimmy had been in pictures before the fifty young “dramats” were even born. All of them, however, had seen his Academy Award-winning performance as George M. Cohan, the famous song-and-dance man, in “Yankee Doodle Dandy.” In fact, that was the first thing they asked about. They wanted to know how Jimmy had approached the character, since Cohan was as “loaded with mannerisms” as Cagney himself in the early days.

Jimmy grinned, amazed at how alert and serious-minded these students were. Mostly twenty-two, they had been ten or twelve when “Yankee Doodle Dandy” was first released in 1942. Yet, even then, they had been studying motion pictures as an art form as well as an entertainment medium.

“It wouldn’t have been Cohan,” he replied, “not without the mannerisms. So whenever I was playing him on-stage, doing one of his song-and-dance numbers, I flew all over the place. But off-stage, in the scenes depicting his private life, I played him straight. I didn’t want the impersonation to get in the way of the performance. You see, first of all, Cohan was a human being—then a performer.”

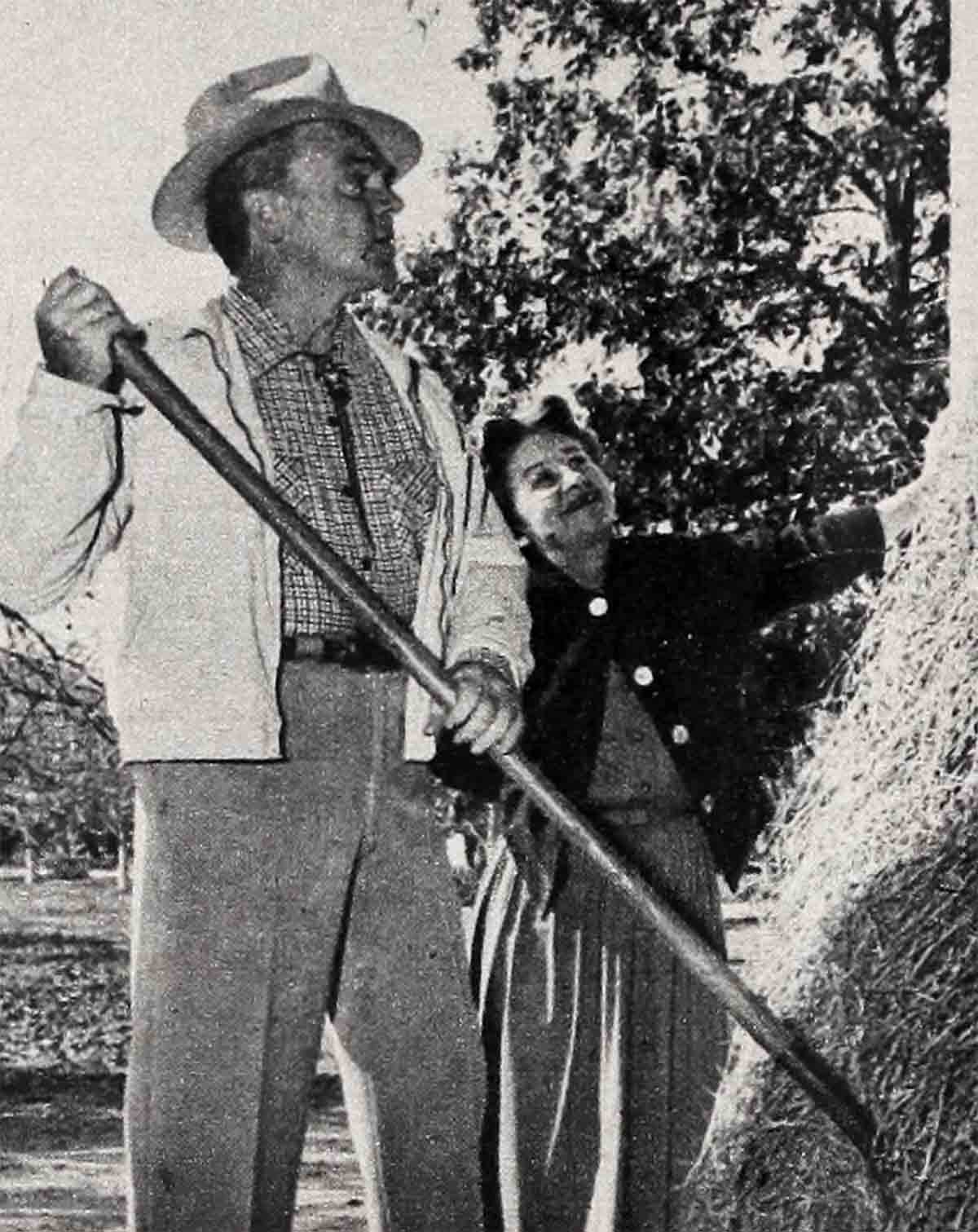

In his own life, too, Jimmy has insisted upon being a human being first—then a performer. All the glamour that attaches to him as a Hollywood star is by virtue of his acting on-screen, not off. In private life, he is strictly a family man. He and Billie (Frances Willard Vernon) have one of the town’s most successful marriages, simply by making their life together a “fifty-fifty proposition.” They met when both were in the chorus of the Broadway musical, “Pitter Patter.” Married on September 28, 1922, they have been working together ever since, first in vaudeville, then operating a dancing school in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and now as farmers. They not only live on a ranch in California’s San Fernando Valley, where they raise trotting horses, but commute to a two-hundred acre dairy farm at Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts.

The Cagneys have never been part of Hollywood’s night life. A columnist recently asked Jimmy where he had been keeping himself since he hadn’t seen him in ages. “I like it at home,” he replied. And home, to the Cagneys, means James, Jr., aged sixteen, and daughter “Casey,” aged fifteen. It means quiet evenings with good books, good music and good friends. It also means time for Jimmy’s special interests. He draws a bit. “But then, who doesn’t?” he asks. He dances daily, not only as a physical conditioner “to take off lard and improve the wind,” but “to get up new routines—you can never tell when you’ll need them.” In addition, he experiments with barnless farming (“When you don’t have to build a barn, you save money,”) crossbreeding cattle and is something of an authority on soil conservation.

The world itself has always been more exciting to Jimmy than Hollywood, and how he lives, more important than how he makes his living. But the one affects the other. The kind of actor you are, the quality that determines whether audiences like you or not, depends not so much on mannerisms or tricks of techniques but on what kind of human being you are. And that’s why, when the students wanted to know the first step in becoming an actor, Jimmy made a gesture that included the entire campus and said: “Get this early stuff behind you as quickly as possible.” College is only a preparation. The important thing is life itself.

If the students seemed surprised, it was because they had heard Jimmy’s speech when he received his honorary degree. Speaking on conservation and what it means to the South, he not only traced this history of conservation from the end of the Civil War but knew what conservationists are doing today and what still remains to be done. Surely someone who had made a scholarly speech like that wasn’t going to underestimate education!

Jimmy smiled. A fond smile, for he was thinking of Mama and how proud she would be if she could have seen him made a Doctor of Humanities. She had insisted that all her children have fine educations. As a matter of fact, Jimmy was only eleven when she made him go with her to a lecture at the East Side Settlement House in New York. The subject of the lecture didn’t matter; it was learning. But the speaker happened to talk about conservation, which explain’s Jimmy’s lifelong interest in it. Hearing the lecturer describe how the Dust Bowl was covering up orchards, young Jimmy resolved that one day he’d go to agriculture school.

But he was only to complete one semester of college. He had been attending Columbia University, working at night to pay his way, when his father died, leaving his mother with four sons and a baby girl. As the second oldest child, Jimmy felt it was up to him to help support the family. He quit college, but like any actor who hopes to grow in stature, he has continued his education all his life. And he has learned from personal experience as well as from books.

No, Jimmy was not one to underestimate the value of an education. But for an actor, time is of the essence, and the sooner these students got started, the better. College is a fine background for any career, but acting is something that can’t just be studied. It takes practice and experience.

“Go out where it’s being done,” Jimmy advised, “and go and do it.”

And he didn’t mean Hollywood either. He recalled the time that he and Billie, in their vaudeville days, were stranded out there. Jimmy tried every studio—the same studios that now compete for his services. But then, they weren’t interested.

The same is true now. You don’t get started in a movie career by knocking on casting-office doors. Hollywood must come to you—and it still does—but not till you’re ready. And when is that? When you’ve learned how to package your talent so attractively that someone wants to buy it. Like any kind of merchandising, it takes more than the quality of a product to sell it. It takes displaying that product to the best advantage. And this is something you can only learn from experience, by testing your talent in front of all kinds of audiences.

“The Seven Little Foys”

Clark Gable had the same experience as Jimmy in Hollywood. When he was working as an extra at $7.50 a day, no one “discovered” him on the set. No producer recognized that here was movie material. It wasn’t until he worked his way up from stock to the Broadway stage that Hollywood found him playing Killer Mears in “The Last Mile.” And even today, the Marlon Brandos are recruited from the stage. The Charlton Hestons and James Deans are discovered, not in college plays, but on television.

The problem, of course, is getting started. But it can happen right in your own home town. If you sing, dance or do an act, you can try your local radio and television stations. You might have to work for nothing, at first, but at least it’s a start. And then there are the big amateur television shows on national networks that recruit talent from all over the country. If your town has a little theatre group, that’s as good a place to start as any. It doesn’t have to be the theatre or television, however. Esther Williams was a swimmer. Doris Day sang in a dance band. The important thing is getting out where your talent can be seen, then working your way up—improving your talent—so that more and more people want to see it.

To do this, you will have to make your own breaks and your contacts. In show business, contacts are a must. But they don’t have to be big shots. They can be other people, like yourself, also interested in acting. Jimmy, for example, got his first big break—a part in a Broadway play—because Victor Kiliam, an actor friend, arranged an interview with the producers.

Yes, but how did he get started in the first place?

Jimmy smiled. “I got my start wrapping packages in Wanamaker’s department store,” he replied.

This time, the contact was a friendly salesman who had connections in vaudeville. Through him, Jimmy got a twenty-five-dollar-a-week job as a female impersonator—the act used six boys as chorus girls. Jimmy had never taken a dancing lesson in his life, but he picked up the steps quickly. He has been picking them up ever since.

“I’m a hoofer,” he claims. “I’ve always been a hoofer.”

It was his acting, however, that first brought him to Hollywood’s attention. In 1930, Jimmy and a young girl named Joan Blondell appeared in a play called “Penny Arcade.” It turned out to be a hit, and Al Jolson bought the screen rights. When he sold them to Warners, Jimmy and Joan went along with the package, repeating their roles in the version, re-titled “Sinner’s Holiday.” After a long and successful career at Warners, Jimmy eventually rebelled at playing nothing but hoodlums. “I’m sick of carrying a gun and beating up women,” he declared, and formed his own producing company with his brother, William. Together, they made such pictures as “A Lion Is in the Streets,” and “Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye.”

So, when Hollywood insists that times have changed, Jimmy—as a producer—is quick to agree. Times are tougher than ever, what with rising costs and competition from television. But for actors, things couldn’t be better. There are now more community and summer theatres than there were when Jimmy started out, and many of them now operate on a professional basis. And television has helped immeasurably, using a constantly increasing number of actors. It is not only a training ground, but provides a perfect showcase for Hollywood. There is not a motion-picture producer or director on the West Coast or the East who doesn’t watch television regularly for new talent. As for the Broadway stage—that spawning ground for so many picture stars—even that is a much more comfortable place to be now that television is giving so many of its actors a steady livelihood.

There is still, however, no easy road to stardom. “It’s a rough business,” Jimmy insists, “because it depends too much on circumstances—circumstances outside your control.” It means working your head off so you’re ready for a lucky break—if it comes. And, sometimes—going hungry.

“But don’t write any of those letters home. You know the kind—Dear Ma and Pa, Please send . . .”

The fifty students smiled back at Jimmy. Yes, they knew the kind.

“It doesn’t work,” Jimmy said, “getting help from home. You do better on an empty stomach.”

He wasn’t advocating going hungry for art’s sake, but rather for life’s. An empty belly will make you take any kind of job—so you can eat. But learning how to do that job is what builds up your confidence as a person and marks the beginning of your real education as an actor; that’s how you learn about life, people, yourself.

When Jimmy was starting out, “There was no such thing as being choosy—and it was nothing to work twenty-six hours straight.” As a boy, coming from a working family, he worked nights after school and during summer vacations, “And every penny of it went into keeping a family of five kids in hand-me-down clothing and not-very-fancy groceries.” Even after he had broken into show business, during layoffs, Jimmy took any job he could get. “It didn’t matter what kind—anything to eat and to learn how to do it.” As a result, in addition to being a dancer, actor and professional farmer, Jimmy has also, at one time or another, been a copy boy, a racker in a pool room, a bellboy in the Friars Club, a Stock Exchange runner in Wall Street, a book handler in the public library, a switchboard operator and a waiter in a tearoom.

“When I was ham-and-egging around New York,” he recalled, “I’d try anything. I remember they needed someone for a vaudeville sketch and could pay sixty dollars a week. ‘You can’t take it,’ my friends told me. ‘What do you know about vaudeville?’ ‘Nothing,’ Jimmy admitted, ‘but on the other hand, how do I know I can’tdo it?’ That’s the principle I’ve been working under ever since.”

So he told the fifty young hopefuls at Rollins College, if you really want to be actors, “Go out where it’s being done—and go and do it.” And if you’re determined to be a star in motion pictures, never give up—never say die. Even age has nothing to do with it. You can be an unemployed actor, not make a picture in two years, and then suddenly . . .

Jimmy winked. In the past twelve months, he had completed four big pictures for three different studios—starring roles as varied as the tyrannical captain in “Mister Roberts,” the western sheriff in “Run for Cover,” George M. Cohan in Bob Hope’s “The Seven Little Foys” and Marty, The Gimp, in Doris Day’s “Love Me or Leave Me”—the story of Ruth Etting. At fifty-one, Jimmy Cagney is the hottest bet in Hollywood today.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1955