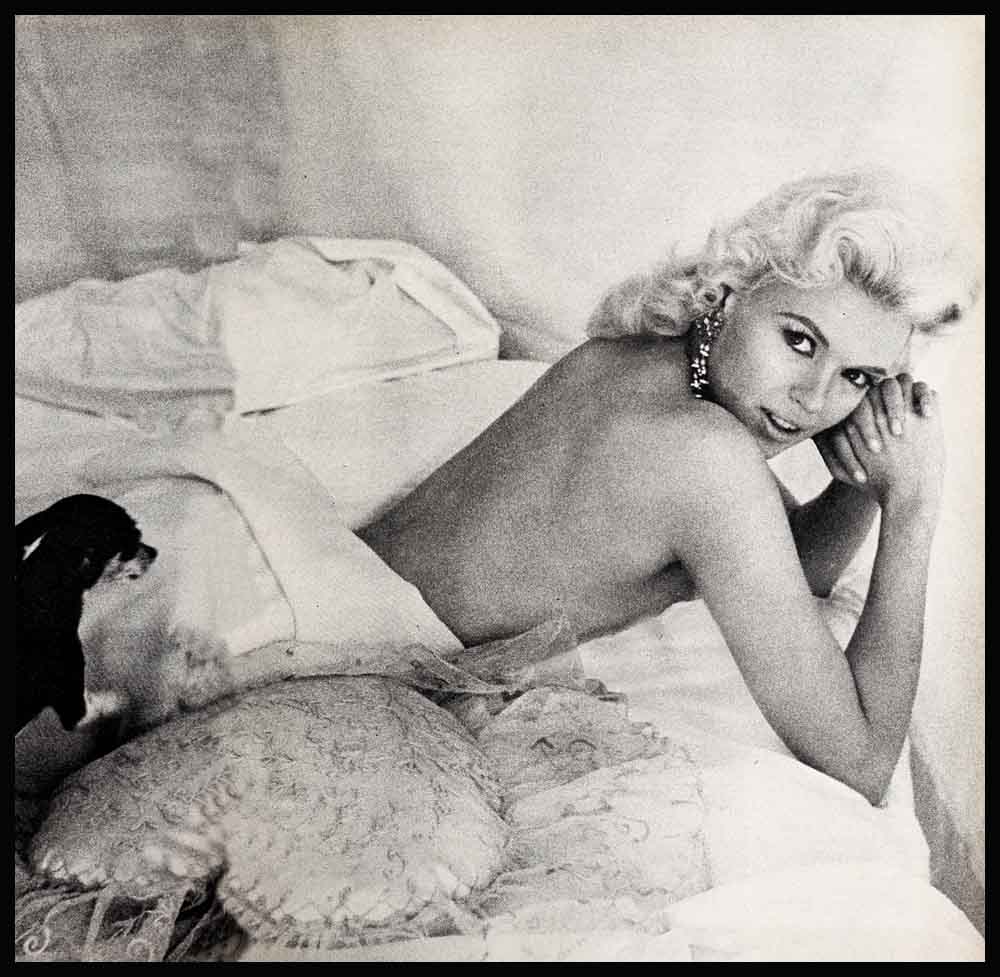

Has Hollywood Lost Its Glamour?

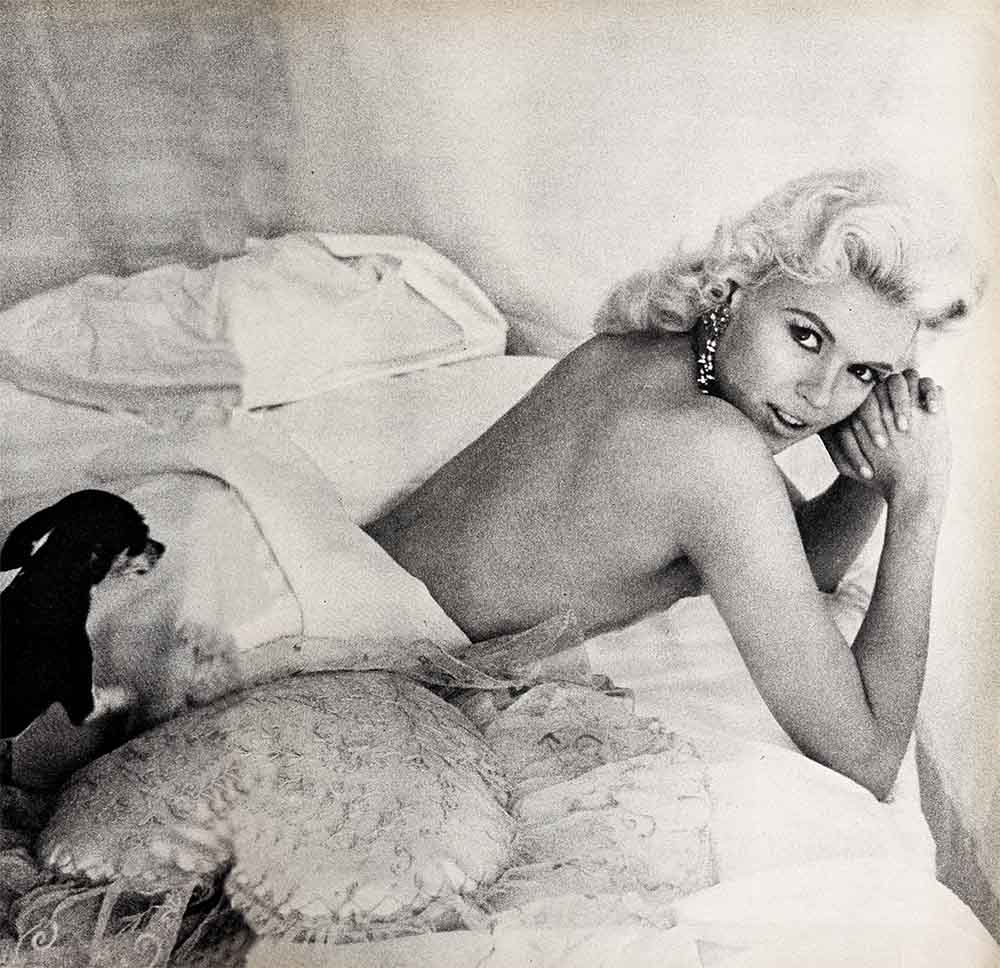

When Jayne Mansfield showed up at a lavish party recently she made a grand entrance, wearing a sheath of shimmering gold that hugged her body as closely as nature would allow. Casually trailing $20,000 worth of champagne mink, junoesque Jayne matched stare for stare. One of the female guests snapped cattishly, “What’s she trying to do—set the clock back thirty years?”

“I sure hope she does,” was the fervent reply of a nearby male.

The next morning, answering her critics in a bikini fashioned from what, one photographer cracked, “must have been the smallest leopard in the world,” Jayne flared: “Hollywood’s getting to be a community of staid married couples. After all, this town was built around glamour, not babies!”

And so it was. Those early years of Hollywood—they were the brightest, maddest, gayest and wildest in the history of motion pictures. It was the golden era of movie queens and movie kings, of sudden wealth, spectacular glamour, of tragedy and scandal, of pomp and show and circumstance.

Locked behind the wall of silence that encompassed pictures in the Twenties lies this whole fantastic world of silent movies and its people—Valentino, Norma Talmadge, the Gish sisters, Wally Reid, Garbo and Gilbert, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin.

The mansions that rang with their festive parties stand quiet and serene in the smoggy sunshine of Sunset Boulevard. Most of them are remodeled beyond recognition, some have become pitifully passe. The bright spots that found the old-time stars at play are no more. Only a remodeled Cocoanut Grove, where Joan Crawford kicked up a wild Charleston, remains; a monument to an era gone forever, along with its gayety. The Daimlers, the Stutz Bearcats, the Pierce-Arrows, resplendent in zebra linings and silver hubcaps, no longer glide along Hollywood Boulevard. One no longer glimpses the white-toothed smile of dark-complexioned Valentino or the jolly bulk of Fatty Arbuckle behind the wheels of their flashy roadsters. And of course one no longer hears the horn of Wally Reid blasting out “Yankee Doodle Dandy” at corner intersections.

Gone, too, are the liveried chauffeurs, the white, fur-robed Cadillac of Norma Talmadge, Billie Dove’s baby-blue block-long Pierce-Arrow, lined with the softest of blue velvet with chauffeur’s uniform to match. Gone, all of it, gone.

Hollywood was a world apart in those days, peopled with creatures born to adoration by a movie-struck public. Pictures were still new, unique and awesome and the people in them far beyond the mundane workaday world outside. The public, of course, knew nothing of Valentino’s ulcers or Clara Bow’s emotional problems and would have shied away from dry subjects that robbed their idols of glamour—subjects so freely discussed among present-day stars.

Francis X. Bushman was dethroned by the very public that elected him “King of the Movies” when knowledge of a wife and children came to light. Nothing so prosaic as babies and exchanged recipes for upside-down cakes ever appeared in print. Movie stars in the silent Twenties were America’s royalty, and the public kept them securely and lovingly on their thrones.

The stars themselves worked at glamour. They knew its value. And movies grew and prospered. Of course, no one could foresee the advent of a tiny ogre called the microphone that would eventually shatter their world. But while it lasted the stars lived their glamourous lives to the fullest. And the world loved them.

They each played their part. The comics, the heroes, the heroines, the villains. And, of course, the cowboys. Never has there been a movie cowboy to equal the unbelievable Tom Mix, with his all-white cowboy suits and hats, his diamond belt buckles and gold fittings. His white Cadillac, upholstered in pony skin, bore the gold-encrusted initials TM that were to become his trademark. They appeared interlaced on the amazing wrought-iron gates that enclosed his hilltop mansion, and on its roof stood the huge letters TM blazing away in white lights. Neon had yet to be heard from.

Out in the San Fernando Valley, the great William S. Hart, the most famous of all cowboys, lived quietly on his ranch—with newcomers Buck Jones, Harry Carey and Hoot Gibson hot on the trail of Hart’s sombrero and saddle fame.

On Whitley Avenue, in the heart of Hollywood itself, lived Valentino, the greatest of all screen idols. Then the most famous star in movies, he had married the exotic Natacha Rambova. She broke his heart, this Natacha, for Rudy loved the strange woman who cared nothing for Hollywood and its people, and very little for Rudy. With half the women in the world worshipping the dark-eyed Italian, it remains an ironic twist of fate that Valentino failed to win over the one woman he loved most.

The Whitley Avenue house became the mecca of artists, sculptors and the elite of Natacha’s world, who gaped at Rudy’s golden boat-shaped bed, the purple velvet draperies at the bedroom windows and the black patent-leather and scarlet-satin furniture that graced his huge living room.

Rudy’s death in New York precipitated a riot that for sheer bedlam will go down in motion picture history. Natacha had left him. Pola Negri, then enamored of the star, paced the rooms of Falcon’s Lair, newly purchased by Valentino but never lived in, like a caged tiger. Her cross-country train trip to attend Rudy’s funeral, her emotional shenanigans at his bier, never, never have been equaled. Drama the public wanted—drama she gave them.

With little or no income tax to gobble up their wealth, with salaries high and living costs low, Hollywood glimmered and glowed in its wonderful prosperity. Gloria Swanson had turned down $20,000 a week to form her own production company. Mary Pickford was paid $1,050,000 for three pictures by First National. Money poured in. And money poured out.

Imported mosaic tiles lined the swimming pool of Pauline Frederick and a carved teakwood teahouse rested beside the enormous pool of Charlie Ray. inside Charlie’s bathroom, an embossed tree of life adorned one of the panels, with jewel-encrusted pockets projecting from the tree. In each of these pockets reposed a toilet article, imported soap, toilet water, dusting powder and makeup for the ladies.

Whole palaces were leveled throughout Europe to supply Marion Davies’ beach home with panels, mantels, doors and bric-a-brac. The walls were hung with priceless paintings from abroad, and solid gold knobs and fittings graced the innumerable bathrooms.

Observed a visitor from the East to this Babylon of the West, “It’s beyond belief. In almost every home one sees old masters and fabulous antiques.”

The Benedict Canyon estate of Harold Lloyd boasted a private golf course, waterfalls and swimming pools. Charlie Chaplin owned a block-long movie studio on the corner of La Brea and Sunset, maintaining his own crew, prop rooms, advertising and publicity staffs. A huge pipe organ in his home near Pickfair pealed forth its somber melodies late into the California night.

Behind Fatty Arbuckle’s home stood a private gas pump, where friends could fill up their cars to their heart’s content. A buffet of delectable foods was always ready for anyone who cared to drop in. Homes were overstaffed with servants and proud peacocks roamed the lawns—a mark of true opulence.

Parties were rowdy or elegant. Or both. Invitations to Mickey Neilan’s gay fetes naturally included all-night swimming. Orchestras played as butlers nonchalantly handed liquid refreshments in crystal goblets to the bathers as they swam. Or sank. Or both. Uninhibited gaiety was in order.

But on the whole Hollywood strove for elegance in parties and achieved it. The Mayfair dances were the epitome of charm and beauty, with stars dressed to their teeth in their bespangled fripperies. Perky flapper Colleen Moore threw one of the prize parties of the era, in a large frame house that was in the actual process of being moved from one part of the city to another. As the house slowly rolled down Wilshire Boulevard, the guests within waxed merry.

A famous Charles Ray party lasted through dawn with the music going strong and the array of food constantly replenished till daybreak. When the sun rose over the hilltop, Charlie, holding his wife Clara by the hand, made an announcement: This was their farewell party. That day Charles went bankrupt. Taking leave of his friends, he was reduced to becoming an extra. He never rose above this, for the caste system then was rigid.

For sheer snobbery there has never been anything to equal Pickfair, with Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford the acknowledged King and Queen of Hollywood. An invitation to Pickfair was a royal command and, until such an invitation was received, no one could count himself a social success. Visiting royalty, social lions, famous people such as Bernard Shaw, were feted at Pickfair where the service was elegant and the taste impeccable. The finest silver and china and food, liveried servants—one behind every chair—marked the mansion. And it was here at Pickfair that a plump young starlet was to meet defeat. Her name was Joan Crawford. But that comes later.

Gloria Swanson was the Symbol of suavity and high-style elegance. Her Mack Sennett days and marriage to Wallace Beery far behind her, Gloria reached out for class. When huge aigrettes in complicated hairdos, beads and bangles and miles of chinchilla fur were the order of the day, Gloria outdid everybody. She outdid many of them in husbands, too. And not only in quantity, but quality.

The hysteria that shook Hollywood when Gloria snagged the handsome Marquis Henri de la Falaise as a husband was frightening. Met by a delegate of bigwigs from her studio upon her return from Europe, Gloria and her bewildered Marquis found themselves in a mile-long parade, waving frantically from the rose-bedecked limousine to the “peasants” that lined the boulevards. Bands played, streamers streamed and across Hollywood Boulevard huge banners read, “Welcome Home Gloria and Hank.”

Later the glamourous Connie Bennett stole the still-bewildered Marquis and annexed him as her own. But as Queen of the Paramount lot, Gloria reigned supreme. That is, until the famous Pola Negri was ensconced in the dressing room next door. Then the feud was on. Learning of Pola’s abhorrence of cats, Gloria had every alley cat within miles rounded up and secretly placed in Pola’s dressing room. The howling and yowling, the swoonings and groanings and the beating of breasts that followed were fearful indeed. Finally, in despair, the studio deported Gloria to the Kingdom of Paramount in the East while Pola reigned in the West.

When scandals broke they were neither stingy in scope nor dingy in consequence. The murder of handsome director William Desmond Taylor inadvertently involved Mary Miles Minter, the latest threat to Pickford’s crown, and overnight ended her career. The death of handsome Wally Reid, victim of dope, stilled the gaiety for awhile.

Fatty Arbuckle, the rotund funny man, sank into obscurity after a feminine guest died under sensational circumstances following a rowdy party given by the comic. The trial made headlines for weeks, with fans agog over the wild and woolly doings of Hollywood. Defeated and dejected, Fatty, for a time, hung about the fringes of the bright world that had once been his and then was gone.

It was the era of clear-cut talent classification. The heroes were always heroes and never since has there been a more virile and handsome group of men. Thomas Meighan, Earl Williams, Dustin Farnum, Harold Lockwood, Conway Tearle, Richard Barthelmess, James Kirkwood, Richard Dix, Rod La Rocque, Ronald Colman, Cariyle Blackwell, Ramon Novarro, Jack Gilbert, Ricardo Cortez and of course the Barrymores.

Lionel, tall and stalwart, survived from the earliest days of movies to take his place as a leading man. But it was John, with his marked handsomeness, that brought distinction and perfection of talent to the screen. Long before his disintegration—which certain producers made Capital of—John Barrymore was the greatest of his day. Unhappy, hell-bent on self-destruction, John married his beautiful leading lady, Dolores Costello, and began the pitiful trek down hill. The long walk that joined his bedrooms with the day time living quarters was at one time lined with cages of snarling wild animals that reduced the visitor, to say nothing of his wife, to shivering wrecks.

Makeup reached a peak never dreamed of with Lon Chaney’s “Hunchback of Notre Dame.” Sentiment oozed from the pores of Janet Gaynor’s and Charlie Farrell’s “Seventh Heaven,” and the “spectacular” of the Twenties, DeMille’s “King of Kings,” made history. Comedy reached its peak with Harold Lloyd, Harry Langdon, Laurel and Hardy, Buster Keaton, Ben Turpin and the world’s greatest pantomimist, Charles Chaplin.

The women of the silent Twenties were every inch and every pound real women. No one starved or dieted or fretted over figures. Norma Talmadge, dark-eyed and beautiful, was the reigning queen of romance, with sister Constance, Colleen Moore and Dorothy Gish the bright comediennes. Lillian Gish literally reduced the paying audiences—20$ to 50c on an average—to blobs of anguish in “Broken Blossoms” while snappy, peppy Bebe Daniels went to jail for speeding. For fifteen days the Santa Ana jail was the mecca of all Hollywood as Bebe played the gay hostess in her flower-decked cell.

It was the era of slogans, with Barbara LaMarr the woman “Too Beautiful to Live” and Mae Murray “The Girl with the Bee-Stung Lips.” Corinne Griffith became “The Orchid Lady,” dainty Marguerite Clark “Little Queen” and Mary Pickford “America’s Sweetheart.” Lilyan Tashman, “The Lady of Taste,” was the first to introduce an all white-and-red decor, and plump, fantastic Theda Bara was “The Vamp.”

“Born under the shadow of the Sphinx and reared beside the Nile,” according to her press agent, Miss Bara was a stout and gentle lady born Theodosia Goodman in Cleveland, Ohio, who dearly loved nothing better than a good dish of corned beef and cabbage—a secret well kept from her fans and even Hollywood itself. With the advent of the Twenties, Theda’s barebosomed glory slowly faded away and the statuesque Betty Blythe became the bead-strung “Queen of Sheba” and Clara Bow the “It Girl.”

In the late Twenties two events occurred that changed the entire course of motion-picture history: a tall, stocky Swede named Garbo slipped into town and Al Jolson sang aloud in “The Jazz Singer.”

Talkies were on their way.

Hollywood had never seen the equal of the sizzling love scenes between the beautiful Garbo and the dashing Jack Gilbert, who was to die a few years later of a broken heart—the first real fatality of the talkies; an idol whose soft and timbreless voice cost him his title of “King of Lovers.”

Photoplay said at this time: “In the history of the world there is no race of demi-gods whose fame is so zealously and jealously guarded as motion-picture actors.” Just about that moment a wildcat from across the border, one Lupe Velez, leaped into the long arms of a lanky cowboy named Gary Cooper, and the “jealously guarded fame” did a nosedive into low comedy.

To friends in her Mexican home or to friends anywhere, Lupe would scream, “Look at heem. He is bee-ootiful,” and wrap herself around the gangling Cooper. It was a front-page three-ring circus from first to last, and the “last” came when Coop, gradually stepping from Westerns to drawing rooms, trekked ofi on a big game safari in Africa with the Countess di Frasso and came back a gentleman in taste and clothes. And saw Lupe no more.

And then the status of the movie star gradually changed, during the Thirties. Fans now began to regard their idols as less than god-like. Rather they were men and women who talked and blabbed and gabbed like everybody else. With this awareness, much of the old glamour slipped away. Possibly forever.

The stars themselves willingly stepped down from their pedestals to gossip, by way of the fan magazines. Hidden families were disclosed, romances were discussed and aprons were donned for housewifely photographs.

Out M-G-M way, a curious thing was happening. From the 145-pound bouncing cut-up, a new Joan Crawford emerged in the most amazing metamorphosis of the times. Gone was the poundage, the wild red hair, the thousands of freckles that literally covered her big-eyed face, and in their place stood a beautiful woman. Dubbed by her studio “Empress of Emotion,” the new Joan was chic personified.

Of all the queens from the Twenties, Joan has survived the longest and strongest. Her clothes, her moods that vary and confound, plus a kind and generous heart, are the epitome of glamour.

She had found her own true love in no less a lad than Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., scion to the royalty of Hollywood. Together they prattled in a new language of love, understood by no one but Joan and Doug. Between bites of mustard on crackers—Joan’s favorite slimming diet at the time—they wooed and married while Doug’s stepmother frowned disapproval.

Mary Pickford never accepted Joan. At one point, “America’s Sweetheart” is said to have snapped at her new daughter-in-law, “Don’t you dare make me a grandmother!”

For her first formal reception at Pick-fair, Joan chose a handsome gown with a sweeping train. But even before the drawing room was reached, a rending sound revealed the worst. The train had been ripped by prodding feet. In horror and embarrassment, Joan fled, later to flee the marriage itself.

With the onrush of talkies, desperate movie moguls sought experienced “speaking” people from the Broadway stage. Unsure of their stars, they took no chances, and soon Hollywood sound stages were crowded with the imports. With the advent of the New Yorkers, Hollywood took on a new air of sophistication. Voices toned down, homes grew less ornate, hairdos became sleeker and Adrian of M-G-M became the designer of the age. The chi-chi and doo-dads were rapidly becoming passe. Accents were added to intrigue and amuse as the long line of foreign actors poured in. Garbo had already won acclaim as the greatest actress of all time and now came Dietrich.

Paramount Studios arranged a studio party for the press, eager to glimpse the startling and naughty creature of Germany’s “Blue Angel.” The day finally arrived, the press arrived and Dietrich arrived, arrayed in a long baby-blue organdy gown, accentuating her plump figure, topped by an atrocious fluffy pink hat and carrying a pink parasol over one shoulder. The press gaped, Paramount gulped while her mentor and guide, her mustachioed director, Josef von Sternberg, stood defiantly by.

She caught on fast, this Dietrich. The organdy along with the pounds disappeared, the hair grew lighter, the eyebrows grew higher and a beauty, a rarely beautiful woman emerged. Freely she talked of her little Maria in Germany, and the ever obscure husband, Rudolph Sieber, who today operates a chicken ranch somewhere out in the San Fernando Valley. She was chatty, friendly, easy. Until a new day dawned not only for Marlene but the entire feminine world.

She took to pants. In mannish trousers, coats and hats she strutted her stuff and startled the natives. The birth of slacks for women had dawned and a new Dietrich was born. Aloof, strange and never again the warm and friendly Marlene of old.

The bearskin rugs upon which the silent vamps writhed and wiggled had been sent off to storage, and the beaded beauties had folded their tents—borrowed from Valentino’s “Sheik”—and silently stolen away. In their places strutted a swivel-hipped, bold-eyed, buxom blonde ogling invitation at a tall dark lad from England, who had cast aside his stilt-walking act for movies.

“Come up and see me some time,” Mae West urged Cary Grant, and the nation, to a man, went West. The world accepted Mae’s risque invitation, including even our present-day Navy, who wouldn’t be without their Mae Wests. Cary himself progressed from history-making comedies with Irene Dunne, Katharine Hepburn and Rosalind Russell to be the smoothest and suavest of heroes.

In the years ahead, the crown once worn by Francis X. Bushman as King of the Movies came to rest on the brow of Clark Gable, the most virile and rugged he-man ever to grace the screen. But unknown to Gable at that time, the girl who was to make tragic history as his future Queen, Carole Lombard, sailed away for a honeymoon with Bill Powell. Tragic Carole. Tragic Bill Powell. And heartbroken Clark Gable. What a hand of sorrow Fate was destined to deal them. With a girl called Jean Harlow as a fourth.

She had appeared on the scene all of a sudden, it seemed, this Snow White beauty called Jean Harlow. Actually Jean began as an extra in Clara Bow’s “Saturday Night Kid,” but from the beginning she was marked for notice, stardom and death. And she knew it.

“I’ll die young,” she confided. “There is something I must learn in this space of time and then I’ll go.” Less than a year later the Platinum Blonde was dead. And in the years ahead not one of her many imitators was ever able to take her place.

With Gable, Jean created a sensation in “Red Dust.” The girl with the beautiful body, who gave little thought or time to it, let alone applying a tape measure, was the sex queen of the era. On-screen, that is. Off-screen Jean was a warm, friendly, impulsive girl, who wanted only a home, husband, children and peace. In producer Paul Bern, a charming man, she saw her dreams come true. Or thought she did.

Two months after their wedding Paul Bern killed himself in the bedroom of their home and the aftermath of rumors all but destroyed her. In despair Jean later married cinematographer Hal Rossen, a marriage that ended in divorce.

The second act of this tragic drama begins to unfold with Carole Lombard’s divorce from William Powell. A short time later Carole met Jean’s friend and costar Clark Gable. With Carole—a woman among women, a man’s woman, a beauty, a forthright dame beloved by everyone—it was love at first sight. She worshipped Gable, adored him, married him and, in a way, died for him. In her anxiety to get back to her husband from a 1942 bond tour, Carole took a night flight home and found death on a lonely mountainside.

Fate now closes ranks for the last act of this four-star drama. Harlow, still searching for love and happiness, found it in Carole’s former husband, Bill Powell. Jean loved Bill Powell with an ache that could I almost be felt by those around her. Nothing meant anything to Jean now but Bill. Gladly she would have renounced career, fame, everything for marriage with Bill Powell, the suave and brilliant actor who returned her love but was not ready for a second marriage. He wanted to be sure. To take time.

“If I could cut out the pain of this love with a knife, I’d do it myself,” she once told a friend. But nature did it for her. Jean’s sudden death from uremic poisoning left Hollywood shocked and saddened. In his agony of despair, sympathy went out to Bill Powell. A few months later, he quietly married Diana Lewis, an unknown starlet, and retired to Palm Springs. Critical illness had overtaken him at one point in his life and nobody knows what toll heartache exacted. Gable alone, of the tragic four, remained. With the wife he loved so deeply gone, Clark was destined to search many years before he found happiness again in marriage.

The Thirties’ villains no longer whirled clipped mustaches a la Lowell Sherman and Lew Cody of the Twenties. Instead, they roared in with a burst of violence upon the screen. James Cagney thrust a grapefruit in Mae Clarke’s face, Edward G. Robinson Little Caesar-ed his way to fame, Humphrey Bogart played it cool and easy, while a dark and deadly menace named George Raft flipped a coin to the top. It was the era of gangsterism.

The sparkling talents and personalities of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers gave musicals a glamour they rarely attained after the team split up. others made their own contributions to the Hollywood glamour story. Ann Sheridan added “oomph” to the language, and Veronica Lake’s peek-a-boo bob started a national fad. In “The Hurricane,” a limpid-eyed, sarong-clad Dorothy Lamour made native love beneath tropic palms seem like everyone’s idea of paradise. Though Dotty was later to do a variety of other things—and even publicly burned her sarong on behalf of the war effort—memories of those early island epics make “sarong” and “Lamour” inseparable.

Hollywood thought it would never again see anything like the Valentino craze, but when the Nelson Eddy rage reached its frenzied peak, it seemed like the good old days all over again. Worshipping women threw themselves prostrate on his lawn, and letters of proposals poured in by the thousands. But history began its deadly repetition. Even as the team of those early lovers, Francis Bushman and Beverly Bayne, were forced by fervent fans to marry or suffer extinction, demands were made on Nelson and Jeanette MacDonald, his co-star. When Jeanette chose to marry Gene Raymond, and Nelson to wed Mrs. Sydney Franklin, interest in the pair began to wane. They had let down the world and the world returned the compliment.

The glamour procession continued as a young Viennese starlet floated nude before a camera and made I’ll m history. Though husband Fritz Mandl made futile attempts to buy up all prints of “Ecstasy,” and later divorced her, ravishingly beautiful Hedy Lamarr was already on her way to fame and fortune in Hollywood. So was a well-proportioned brunette who strolled suggestively down a Street in a minor item titled “They Won’t Forget.” They didn’t.

Dark tresses turned blonde, Lana Turner worked her way up through films like “Johnny Eager” and “Ziegfeld Girl” to become one of the top all-time glamour queens.

Plump little Margarita Cansino was getting nowhere as a hoofing extra. But renamed Rita Hayworth, with hair tinted a glorious titian, there was no stopping her. And Betty Grable of the legs turned glamour into one of the great box-office attractions of all times.

A pretty, pleasing starlet of the twenties, Sue Carol, gave up acting, became an agent and married her client, Alan Ladd. As a new-type killer in “This Gun for Hire,” the blond, slight Alan became the rage. It was mainly due to Alan’s appeal and Sue’s help that the last bar between fan and star was forever lowered. The love, marriage, home and children stories given out by the Ladds brought on a whole new Standard of relationship between Hollywood and the public. Glamour gave way to coziness, and mystery to intimacy. Then came Pearl Harbor, and Hollywood took to uniforms. With stars of the motion picture screen joining the common cause of freedom, the last shreds of glamour began to fall away.

The de Havilland-Fontaine sister feud, the Rita Hayworth-Aly Khan nuptials, MM wiggling across the screen with that gleam in her eye, helped recoup some of the lost glamour. Then Marlon rode into town on his motorcycle and threw those last bright shreds to the wind. Today only Jayne with her leopard skins and Debra Paget, with her jewel-studded limousine, can hold a candle to the queens of yesteryear.

Summing it up for Photoplay, Gloria Swanson, looking back on the glorious and glamorous past of Hollywood, says, “The glamour associated with Hollywood in the Twenties and Thirties merely reflected the glamour of the world at that time. There was a freedom and abandon everywhere. Added to this, Hollywood had all the excitement and thrills of a new industry. In a sense we were pioneers. We were working and playing in the last frontier of what had been the wild and very wonderful West.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1957