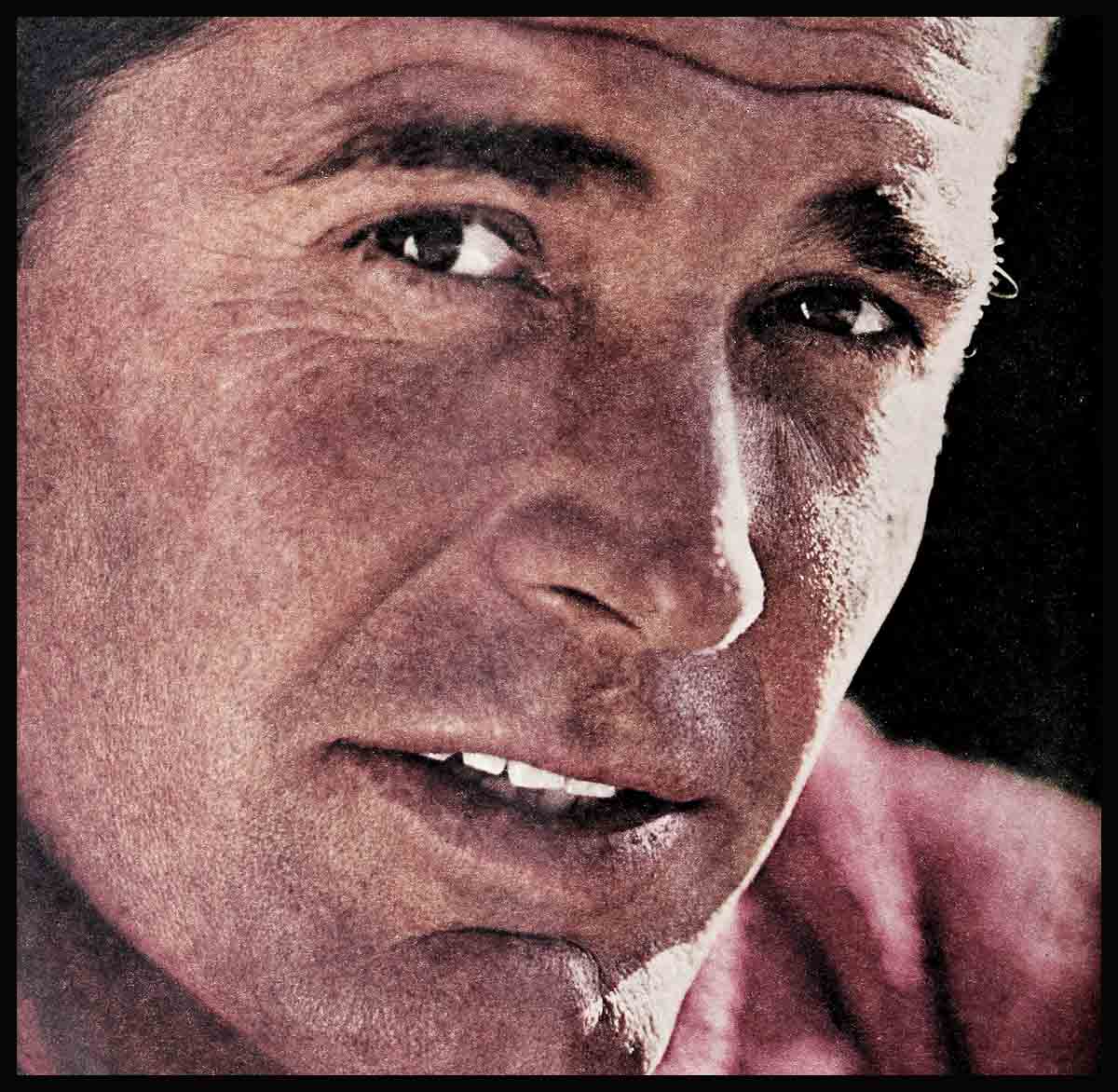

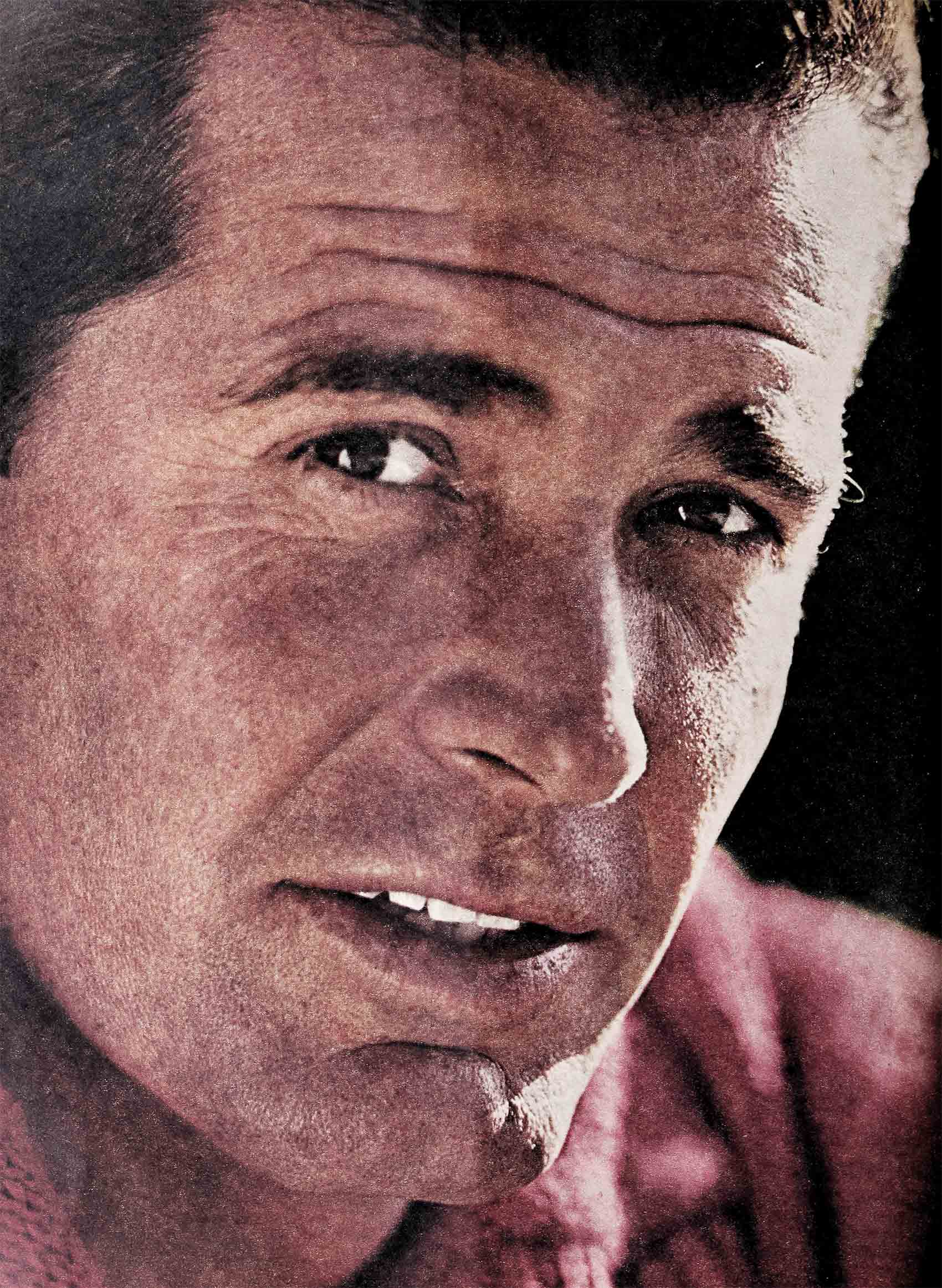

James Garner: “I’ve Never Made A Mistake In My Life!”

Jim said it on the movie set of “Move Over, Darling,” his black eyes flashing to me across the dressing room, daring a contradiction: “I feel I’ve never made a mistake. What d’you think of that for a statement?” From a guy who doesn’t like to make statements! Who hates publicity, shuns it, wants to keep himself to himself, loves the camera, loathes the limelight. What did I think? Well, I thought . . . how about that crooked little pinkie on your right hand, Jimbo, that took the rap time after time when your temper got out of hand, and you had to bust something with that right fist of yours? . . . How about those teen years when you were in and out of school because “all teachers were squares” and there were more glamorous things in life such as pool halls, fishing and hunting?

. . . How about the young rebel who wouldn’t listen when every adult was telling him, “You have a good body, you have a good mind, do something with them.” You once told me, “They wouldn’t stop reminding me of my height and my looks, so naturally I went the other way. One time an aunt of mine even dug up a talent scout, she was so sure I could be an actor. But nothing happened and that was okay with me. I fought being an actor. I never knew what I was looking for.”

. . . How about hitching up with the Merchant Marine at the age of sixteen and almost getting yourself killed? If you hadn’t been on leave, you’d have been at the bottom of the sea when that tug sank in a hurricane with your crew aboard.

. . . How about those drag races on Mulholland Drive with the cops breathing down your neck?

. . . How about the final decision that really switched your life, the day you were laying carpets with your dad and suddenly he said, “Jim, you don’t really want to do this. Go out and get a job you would like. You can live at home; you don’t have to worry about food. You can go two years without working; it’s okay with me. Find out what the hell it is you want to do!” Years later you admitted: “My dad kind of forced me into acting, didn’t he? At least he sent me out looking when I’d never have gone looking.”

. . . And how about that shell you kept yourself locked into until you were twenty-five? Locked in because you were a guy with problems, an introvert, scared of the outside world, afraid to come out?

“It’s a funny thing,” today’s Jim says, “I feel that if I had ever done anything differently I wouldn’t be where I am right now.” Zooming to the top of the film world, he means, with four in a row: “The Great Escape,” “The Wheeler Dealers,” “The Thrill Of It All” and “Move Over, Darling,” all sure hits for Garner, and a wife he’s happy with, and a life he keeps the way he wants, and two youngsters he’s crazy about—all the things the kid from Oklahoma dared not even dream of having.

What Jim means

What he really means is not that he never made a mistake, but that in some wonderful way the good Lord hasn’t made a mistake, that talent doesn’t go wasted in this world, even if the man who owns it tries to hide, tries to run away, doubts his ability, downgrades himself.

“A Marlon Brando I am not,” Jim told me the first time we met. He was Maverick then and giving Ed Sullivan and Steve Allen a run for the ratings. “I don’t know that I have much talent, but I’ve had good luck. There are fifty guys like me around Hollywood, just like me, and you should have seen my first screen test! I was a stiff.”

Big Jim was underrating himself. He was already weary of the Maverick bit, and in those days he wasn’t making much money. The future didn’t look like much. “I don’t kid myself that this is great acting,” he confessed. “I’m just a personality holding down a job. I’m fair looking . . . I have some common sense and I understand people—at least I try.”

The truth is, there’s only one person Jim hasn’t always understood, and that’s himself. In early interviews, he told how his mother had died when he was five and how he’d missed her, how his dad had remarried a couple of times unsuccessfully. He spoke of hating the farm where he was born and raised, hating the long ride to school on horseback. He gave the impression of a kid who’d grown up with a chip on his shoulder, who’d been “on his own since he was thirteen.” Those were the facts and moods that came out in early interviews, and writers wrote their stories with varying degrees of sympathetic understanding—understanding which curled Garner’s hair.

“On my own at thirteen, baloney! When I was thirteen, my father moved to California looking for work and left me in Norman, Oklahoma, with seventy relatives, including two grandmothers, a flock of aunts and uncles, my brothers Jack and Charles, a real barnful! On my own! What a joke. I was just restless and hankering for more excitement than school offered.

“When I was sixteen and went into the Merchant Marine, it was 1944 and every boy my age wanted to get himself a piece of the war. We didn’t have much sense. I stayed in a year, came to Hollywood to stay with my dad for a while and intended to ship out again. But Dad talked me into going back to school. Hollywood High. I played football until I ran into the same trouble I’d run into back home: my grades dropped so low I couldn’t play.

Modeled bathing suits

“About then, a modeling agency called the school looking for guys equipped to model bathing suits. The Phys. Ed. teacher picked me, so suddenly I was making ten bucks an hour and going to Palm Springs for five days on assignments. It was unsettling for a seventeen-year-old.

“My teachers weren’t making that much money! How could they teach me? Why should I listen? I quit and went back to my hometown in Oklahoma and this time made good enough grades to play some serious football—until I busted my knee.”

Jim was always trying to make action substitute for what lie really wanted, self-expression. His older brother Jack was the funny one, the entertainer, “the one who took the attention, the conversation and the girls away from me.”

With self-expression so difficult for him to achieve, it’s no wonder he backed away from becoming an actor. “I’d read about actors in the magazines,” he admits. “The stories were so maudlin they turned my stomach—night club crawling and multiple love affairs. That’s all they seemed to do. I couldn’t have cared less.”

Cared? Scared of the actor’s life would be more accurate. Scared of the night club crawling and the multiple love affairs. As a matter of fact, to this day the Garners keep away from night clubs, keep away from premieres. Jim doesn’t even drink. “Quit drinking years ago,” he’ll tell you. “Figured it’s not good for an actor. I’ve seen too many out here ruined by the sauce. I don’t belt it around any more.”

James Garner is a strong man who has nothing to be afraid of, yet is still afraid. That’s why his life really began with Lois, why his family means so much to him, why the Garners are a closed corporation. They have friends, but not many (“I would rather have one close friend than many”). For the most part, Jim and Lois are people who live quietly together. They don’t spread their emotions thin; they give themselves to each other and to the children.

Says Jim: “For twenty-eight years, I never knew what I was looking for. I guess I wanted roots . . . I guess I’d always wanted roots. I was unhappy. It was my second year in Hollywood and I couldn’t have been more obscure. I had no goal, had no idea what I wanted to do. I had seen a lot and done a lot and there was little left. Lois was the turning point.”

He met her just after completing a dilly of a movie titled “Shoot Out at Medicine Bend.” They met at a pool party where Jim was horsing around in the pool with a dozen youngsters. (“I’ve never met a kid I didn’t like.”) He was the monster they were trying to drag under water. Lois sat quietly watching the game, and what attracted Jim was at once her beauty and her sadness. When they talked, he discovered that her little girl, Kim, then eight, was in Children’s Hospital with polio. Lois was a native who’d lived in and near Los Angeles all her life, wasn’t a bit impressed with actors, had tried acting herself and found it disenchantingly hard work. She was a private secretary at Mark Stevens Productions. Jim describes her as “a sort of lovely edition of Audrey Hepburn, only full-bodied like Sophia Loren.”

He was in love with her within an hour. Six weeks later they were married and he adopted Kimberly and helped teach the child how to walk again.

He not only taught Kim how to walk, he taught her to ride horseback. Today he’s proud of her crack riding, her fine dancing. He’s crazy, too, about his five-year-old Greta. When she was a baby, he walked her to sleep every night until the doctor made him stop.

“She’s only four months old, Doc,” Jim said, “why not spoil her a little?”

Now he knows better, and Greta is not spoiled, any more than Jim was as a kid. He’s drawn on his own experience and realized that you have to learn to take it. “I remember at six having a race with my dad at the Nine Mile Corner. He was in a Model T and I was on my horse. I was beating him, too, until that horse of mine stumbled and fell. Dad kept right on going. I got on again and tried to catch him. I lost the race,” he remembers now, “but not my self-respect.”

He won’t be bested

Jim is the kind of man who won’t be bested. Take his fight to the finish with Warners. In March of ’59 he’d signed a new contract at that studio. “Maverick” was going great guns. A year later lie was notified that his weekly check for $1750 would not be coming to him because of the actors’ and writers’ strike. In addition, Warners wouldn’t allow him to work anywhere else. If he even showed his face on Bob Hope’s TV show, they wanted half. Garner sued and he won—not only terminating his contract, but freeing himself from a series he felt had overexposed him.

“At Warners they owned me, I felt like a side of beef hung up in a refrigerator. From time to time they’d slice off a piece and bring it out for display.”

Though each day is a fight to stay on top, Jim can work hard all day and then leave the actor at the studio and take himself home. “I’d be a nervous wreck otherwise.” There’s no temperamentality; there’s a husband and a father. “When I’m not there, the place falls apart.” And there’s no keeping up with the Joneses. “Hell, I don’t even know ’em.” There’s no talk of show business at home, no reading of scripts. “Just livin’ . . .” The house is complete with white carpets, Japanese and Danish modern furniture. “My wife must give money away, I don’t know what she does with it!”

If Jim’s uncomplicated approach to life hasn’t changed, Jim’s status has—and with that change in status he has come up against a responsibility he abhors—publicity. “I’m not a great windbag,” he says, “In fact, being interviewed makes me feel funny.” It’s an invasion of his shell, the shell he has never entirely emerged from, that he’s still a little afraid to emerge from for fear of “maudlin” stories about the mother who died, or the stepmother he sassed, or the adopted child he taught to walk, or any of the other deeply felt moments of his life.

How phony stories start

“Publicity is the main thing I don’t like. I’d rather play golf than take publicity stills. I’d rather dig a ditch than do an interview. The premieres, going to a preview and watching yourself with the press right there—that’s part of what I don’t like. Phony stories . . . they’re my pet peeve in the whole world. That’s the thing that really bugs me. I think I should hate something and that’s it.”

So he won’t do interviews and that leads to “phony stories.” “And right there,” I told him, “right there you’re making a mistake—the one you say you’ve never made.”

And it is a mistake. But all he says in rebuttal is: “I’ve always looked at this as a career and a business. I want to be in it as long as I can. I’m doing the thing I’m best equipped to do . . . to make my life and my wife and our children’s lives as secure as I can. In no other business could I make this kind of money and enjoy it so much. And yet, this is really the most insecure business in the world. You’re subject to the whims of the public. I’ve taken gambles. When I left Warners, people said. ‘He’s ruined his career.’ I had to have the courage of my convictions, do what I think. And like I say, I feel I never made a mistake. If I had, I wouldn’t be where I am right now—and that’s pretty good!”

What Jim is really saying is that despite every mistake he’s ever made, every foolish gesture, every fear he’s had—even the fear that the public might get to know him—his life has been divinely guided.

I know what Jim means. He senses that everything he’s done, every move he’s made has helped him become today’s Jim Garner and made possible today’s career. He’s right. We are the sum total of our lives, the right, the wrong, the noble and the not-so-noble. We are our own summation. And he is his.

THE END

—BY JANE KESSNER

Jim’s in “The Thrill Of It All,” U-I, “The Wheeler Dealers,” M-G-M, and “The Great Escape,” for United Artists. His next will be titled, “Move Over, Darling,” for 20th.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1963

No Comments