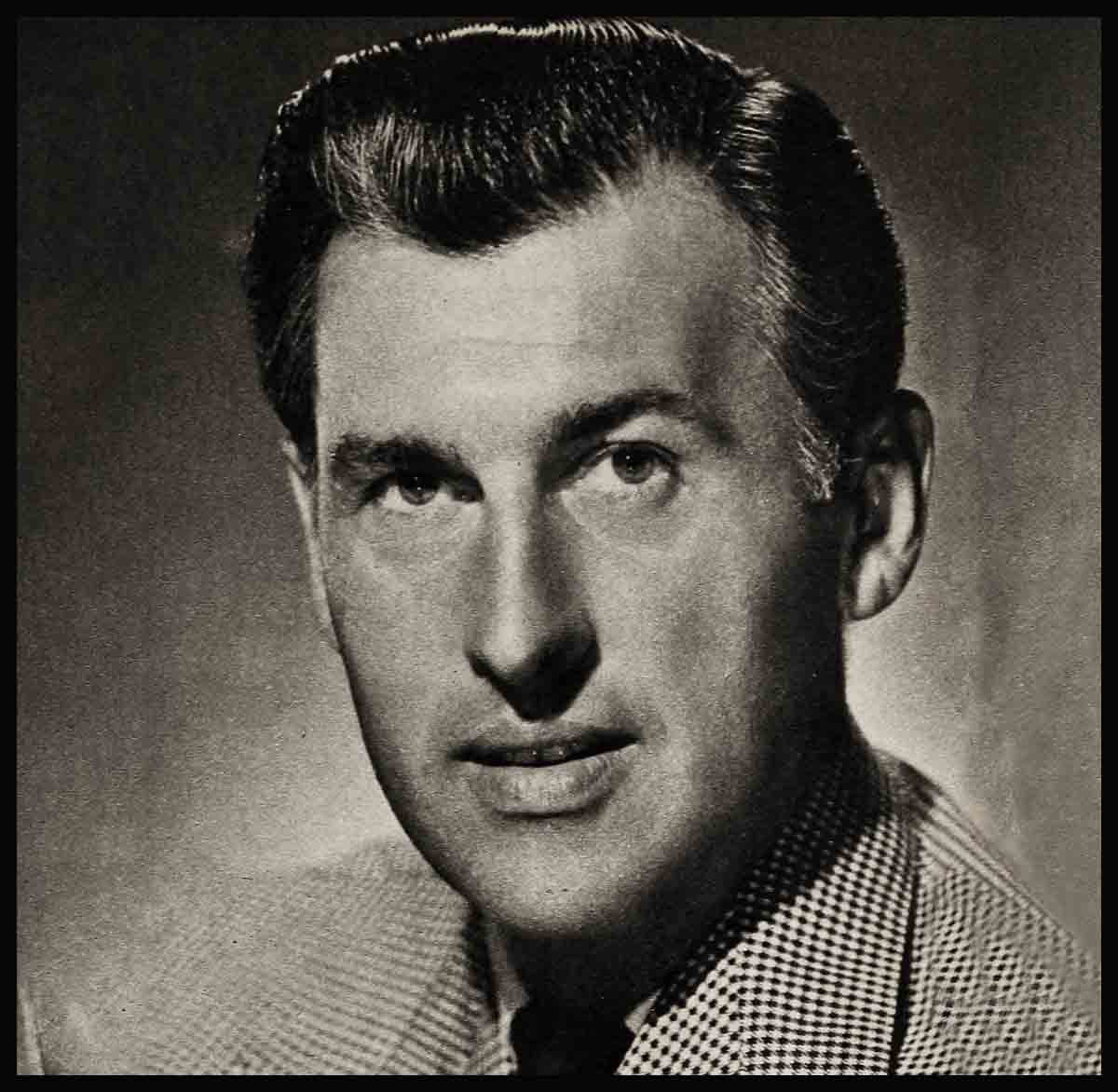

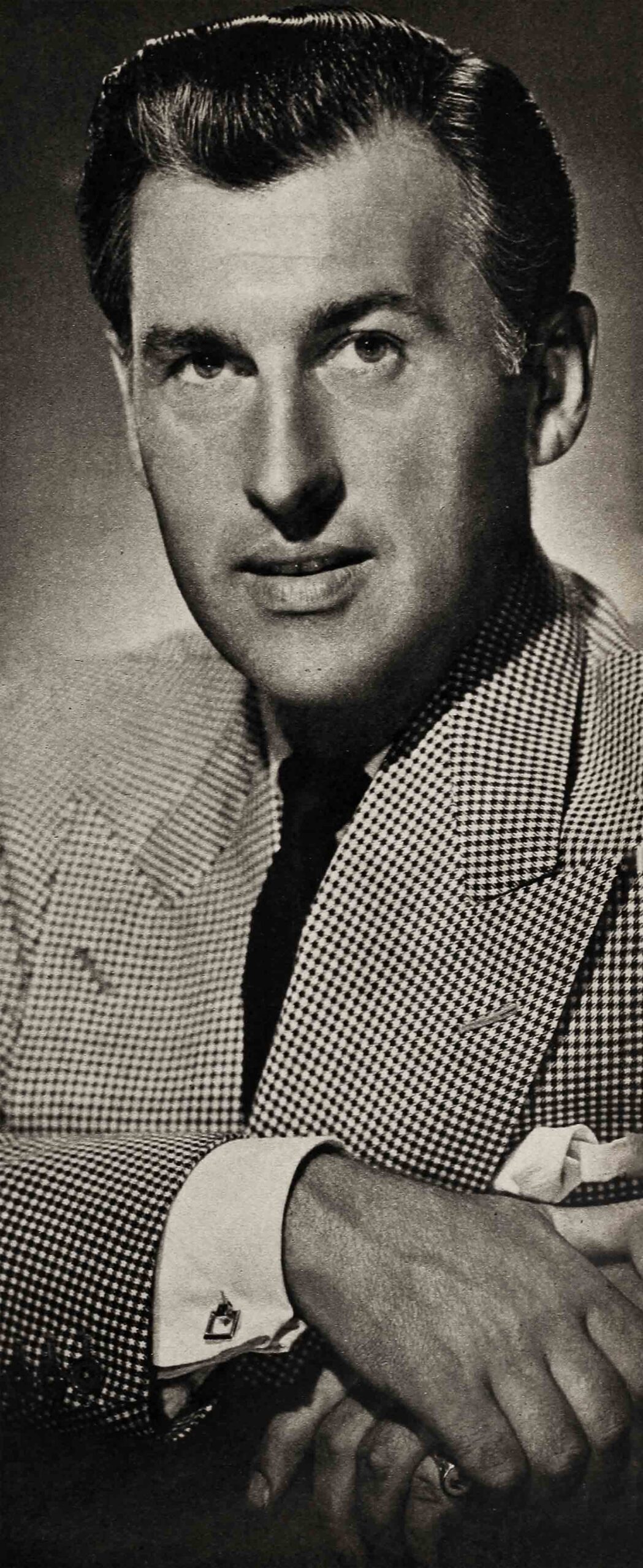

The Courage To Fear—Stewart Granger

The subject of faith is one which Stewart Granger does not care to talk about with strangers—especially strange writers. And the luncheon interview on which this story is based would certainly have been a failure had Stewart not suddenly reminded himself of an old and beloved friend, Peter Bull, whom he recalled as “truly religious.” He had to tell you of his admiration for Peter, and only while speaking of him, did some of Stewart’s own ideas come out.

The Church of England into which Stewart Granger was born is not as possessive as some churches; in the opinion of many students of Christianity it leaves a lot to the individual. One gathers from talking to Stewart that he thinks it is how a man uses this freedom of choice which determines the truth and dignity of his worship. This is where Peter comes in.

“Peter never talked about his religion,” said Stewart. “He had accepted it as a small boy because his father, to whom he was very close, was a believer who fascinated him with wonderful stories of God and the church. Peter was a man who laughed a lot and joined in your fun; he had no need to enshroud himself or his friends with his belief. His favorite church was an odd little chapel on St. James Place, favored by the Grenadier Guards. He would attend service early every morning.

“When you knew Peter long you began to feel how strongly love and honesty must be part of true piety. Peter was a skipper of a landing craft in the British Navy during World War II. He was often very frightened. Yet his men loved him as I have never seen men love an officer, because he never for a moment pretended otherwise—and also because he stayed at his post though he couldn’t hide the fear that gripped him.

“My favorite story involving Peter brings a picture to mind that makes me smile fondly about him every time I think of it. It concerns a time when his ship was being bombed and machine-gunned in Mediterranean waters by Nazi planes. Peter was on the bridge at the time, a bridge, incidentally, where he grew geraniums in clay pots. He ducked every time the planes dived; ducked, and grabbed at his geranium pots to save them from being hit, yelling alternately from fear and from desire for reprisal.

“ ‘Get that fellow!’ he would cry to his anti-aircraft crews, pointing upward at a plane even as he scrooched over with his arms full of geraniums. ‘No! That one! The other one! He’s after my flowers!’

“His men swear that one day, off an Italian beach, Peter’s prayers saved them from certain disaster. They had just put a landing party of soldiers ashore and were about to turn back to sea when an exploding shell put their port propeller out of commission. At this moment they were portside to the land with a stiff on-shore wind blowing and so close that only a sharp turn to right, or starboard, could take them out to sea and safety. But with the port propeller gone the starboard propeller would swing them right into shore.

“Nevertheless, Peter, they say, offered up quick prayers, then signalled for full power ahead. And the ship, against every rule of seamanship, not to say the mechanics of force and moving bodies, turned right! It is hard to believe. It is something like putting your car in reverse and yet having it go forward. And it must therefore come under the heading of miracle works. Yet I was intrigued some time ago to read that the scientists today hold that physical law is not absolute but merely a matter of high probabilities. A teakettle of water over a fire has never been known to do anything but boil, yet, scientifically it is possible for it to freeze instead! God not only performs his wonders, but has arranged loopholes by which they can appear to be natural happenings.”

It is apparent that Stewart never had the advantage of as loving an introduction to religion as Peter had, and he bemoans the fact. When Stewart was born his father was already 50. When Stewart was old enough to understand a bit of what was going on, when he was about nine, his father was almost 60.

“We were almost two generations apart in our views and probably more than that in our habits,” he comments. “Intimate father-son chats, like Peter enjoyed, were not possible. I never had one with him. My father’s death when I was very young provided the occasion for my first intimate relationship with the church, and it was a most painful one for me.

“I stood close to my mother at the services and was conscious of her deep suffering; knew that for her the world had practically come to an end. When it came time for the minister to speak I was certain he would say something which would inspire and comfort her. Instead, he was a man who spoke in the most worn platitudes, spoke with professional dispatch and unction, much like an auctioneer briskly disposing of his wares, and without a trace of genuine feeling or sympathy audible. Even at my age I sensed his inner disinterest in his assignment.

“Naturally I was bitter about it and no doubt youthfully revolted at the whole idea of the church. Later I rationalized, made a distinction between the man and what he represented. There is a difference. Yet, to this day, I wish more attention would be paid to eliminating this difference. I feel that our ministers should be our most sensitive men, our best minds, and, above all, gentle, conscientious, earnest talkers. I am forever offended by holy words spoken in routine fashion.

“I am sure the world of man needs religion. Peter proves that. A world full of men like him would be nothing short of the Promised Land. Peter is religion in action.”

As it is for most people, it is difficult for Stewart Granger to peg his faith, tell how strong it is. One suspects that he feels it is certainly not as strong as that of some men he knows, yet stronger than that of others he has met. Is it strong enough?

The trouble with conscience, as far as Stewart is concerned, is that it can often make a lot of trouble for him. His friends report that in the Army he could not accept the presence and military functions of chaplains. It seemed wrong to him to assemble men before battle, for the purpose of blessing their assignment, when that assignment was to go out and slay their fellow men. He is credited with saying as much, and in the English Army, as probably in all Armies, such talk is not favorably received. Stewart, it is said, got his come-uppance in a steady fare of the more unpleasant duties his superiors could allocate to him.

All he had to do was to hold his tongue but even in Hollywood he is not noted for this gift. He has told off some of the biggest men in the industry, and whether seated in a studio office or on the witness stand in court, has always, and bluntly, made his thoughts plain. As a matter of fact, he doesn’t think that holding one’s tongue is always best described as the practice of tact. He thinks that more often it amounts to the practice of moral cowardice.

“A fellow who wants to get along without unpleasantness often finds himself silent while the God-awfullest things happen in front of his eyes,” he declares. This harks back to his feeling about chaplains in the Army. He doesn’t think war will ever be eliminated if people do not admit to themselves that it never can be sanctified religiously. Yet he does not make statements like these as if he were lecturing. He seems to be lost in his thoughts and they come out as if he were simply giving voice to his conscience.

The distinction between moral cowardice and physical cowardice is one which Stewart is known to have studied for most of his life. He considers the first of these, moral cowardice, the root of the most serious evil in man’s history. He thinks that it permits men to look on injustice with equanimity, or more often lets them turn their backs on it and pretend it isn’t taking place. Whereas physical cowardice, in his opinion, while hardly an inspiring facet of man’s makeup, is as necessary to his survival as his ability to breathe.

He points out that in dealings with his son, Jamie, born of his first marriage, he has had several opportunities to be a moral coward by pretending to the boy that he never had been a physical one. “No man wants his son to think he is a coward but I deliberately made a point of doing so,” Stewart says.

When Jamie was about eight he made a visit from England to see Stewart in California. One late afternoon, after he had attended a Halloween party, it seemed to Stewart that Jamie was being unusually silent and giving evidence of inner anguish. The boy refused to tell what was wrong but from the nurse who had accompanied him Stewart learned that he had been threatened by three boys at the party and she thought he was suffering because he felt himself a coward—he had run.

“Were you scared?” Stewart asked Jamie. “Tell the truth. The truth never hurts. I have often been scared in my life.”

“Have you, really?” Jamie asked.

“Yes.”

Then Jamie admitted it.

“Look, Jamie,” Stewart said. “This is something you must learn. If three boys are going to set on you, run. If two boys—run. If one boy and he is bigger than you—run. If one boy and he is your size, stay and fight. It won’t be terrible. If one boy and he is smaller than you are, don’t fight. Let him run. That’s the way of the world.”

“But isn’t that wrong, Dad?” Jamie asked.

“What could I say,” added Stewart, “knowing that if he doesn’t learn to bend reasonably with the winds that will blow at him in his years to come he will be destroyed?”

So reports that he answered “No.”

“More than anything else I want Jamie to be honest,” Stewart declares. “I want him to know that the fox who flees the hunter’s dogs is honest and without guilt, and similarly the man who runs from that with which he cannot cope. It is dishonest only to run and pretend you didn’t or even that you are better than your fellow man and shouldn’t have; morally dishonest, even moral cowardice. Such a man could also pretend that he is in the church because he loves it, when actually he trembles before it. Such a man comes to God as a hypocrite.

“Not all men bend before life, I know. But for every exceptional youth who has the qualities of true heroism, and, I might add, the stoicism to suffer prolonged martyrdom, you get ten thousand youngsters who become frightened, twisted, little souls trying to live up to impossible standards. In time to come we may all be noble. The lesson of today is that we are not, and most of us must come before our Maker at least honestly as human beings who have sinned, as what we are. Somehow, in admitting our weaknesses, there is a saving grace; enough, I hope, to count.”

According to Stewart he spent much of his early twenties being a foolish pretender about himself. He worried so deeply about a fancied cowardice that he would deliberately pick fights when there was absolutely no provocation. He would challenge a man in a pub because he fancied the man was looking at him insolently. Before he made the challenge he would be shaking inside with fear of what would happen. But he had to do it. “It was a horrible thing,” Stewart recalls.

He used to know Freddie Mills, former light heavyweight champion of England, and would spar with him at exhibitions. They would go to events like picnics staged for the benefit of the English Ford company, and put on a bout before thousands of their workers. Stewart thought that out of such deeds he would rise in his own estimation and be able to live with himself without being besieged by all sorts of doubts. But it didn’t work.

“Nothing worked for me but the truth—the truth about who I am and what I am. And—I’m just another chap. No more—no less,” he says.

“I remember that when I wanted to be an actor I held back from trying until after I was twenty because I thought acting was effete work for a man. I was hardly being honest with myself. What I was afraid of was being accused of being effete. That quite another story.

“When I could admit this to myself went on the stage. There were times when the very accusations I had feared were made. I coped with them the best way I could. I don’t think a man is to be blamed for ducking a blow, but I do think he is wrong to hang back from some desired step because it might bring on a blow. The first is an act of self-preservation, the second is debasing one’s self.”

Out of this interview with Stewart Granger, dealing with matters that he would rather not have discussed (but from which it was against his principles to run), it became apparent that he does not consider it an easy matter to solve one’s spiritual problems. In his honesty he gives the impression that he, for one, has not yet found the formula; the teaching of the Scriptures, multiplied by the number of times he has had to violate them to live in a practical world, has probably not yet equaled X for him—X, of course, being the possession of a pure faith.

“Man is to his God what he is to himself,” is about the most direct conclusion Stewart ventured to make. “You might say I am working on myself.”

THE END

—BY LOU POLLOCK

(Stewart Granger can now be seen in MGM’s All The Brothers Were Valiant.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1953

No Comments