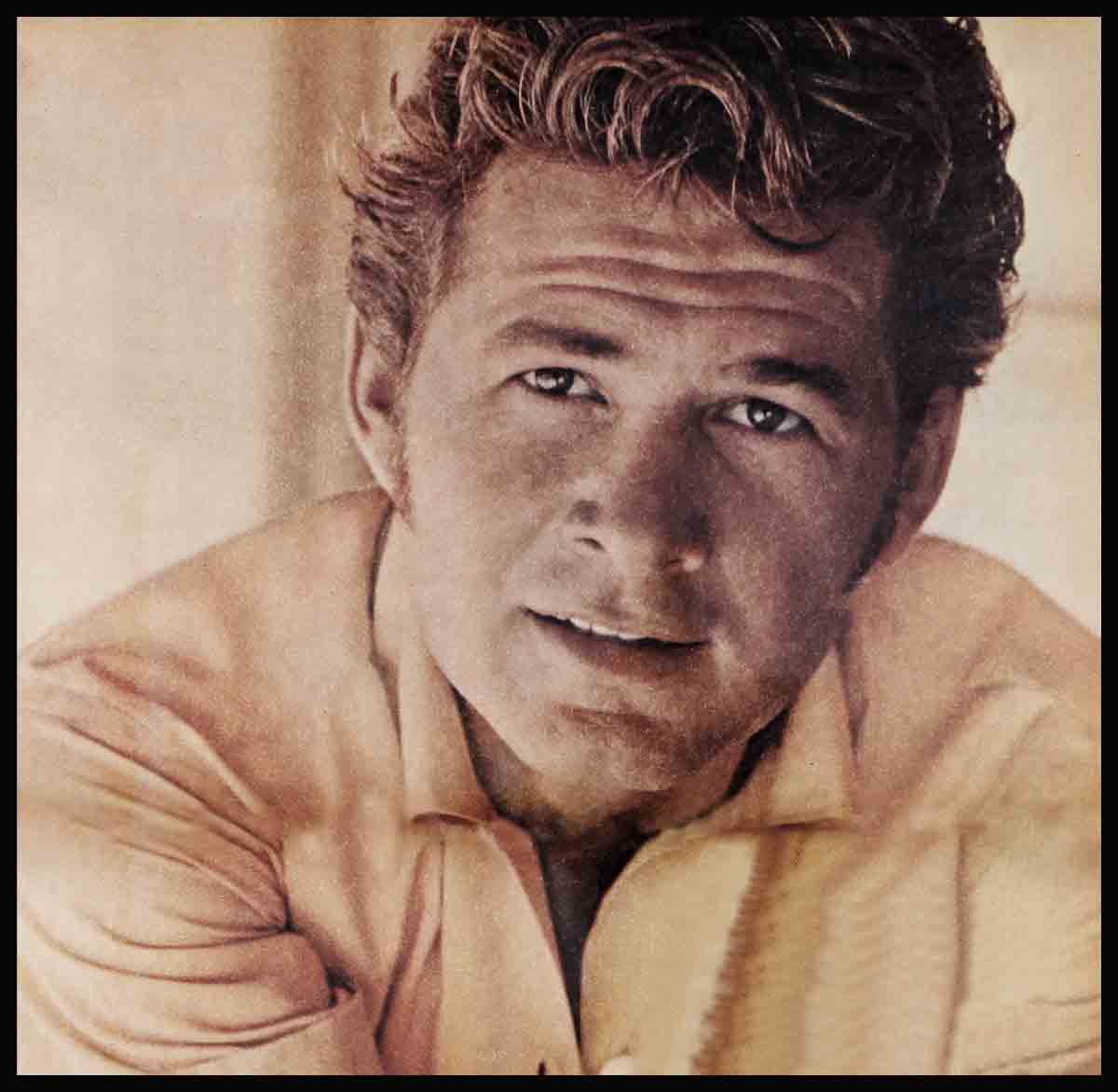

“Let Me Love You Tonight!”—Gary Clarke

Sprawled comfortably in a battered oak chair in the living room of his modest rented house, Gary Clarke toys with the penknife in front of him. Behind Gary’s head, mounted high on the fireplace wall, is a trophy he likes to point to as “a wild goat I once shot over on Catalina Island.”

The goat, distinguished by a pair of huge sunglasses hung on its nose, and an unlit cigarette dangling from its mouth, cocks a reflective shoe button eye over the scene it surverys.

“No, I haven’t yet managed to do all the things I really want to,” Gary says, “even though the part I play on ‘The Virginian’ is a pretty good one. But the thing that really bugs me is The Label.”

The Label! Still all patience, Gary makes an arch of the penknife blade in his hands. He sits silence for a moment. “D image?” he says finally. “Actually, it’s still undefined Maybe it will be clearer in say, a year or so. But the pub lie still doesn’t know who Gary Clarke really is. All the know is, ‘Oh, he’s the kid who used to go with Connie Stevens, remember?’

“Well, that’s one way of de cribing me, but it’s still only a label. Even at the Photoplay Awards, when I was voted ‘The Year’s Most Promising Actor,’ I was introduced as, ‘You know, Gary Clarke . . . the fellow who almost married Connie Stevens.’ That really hurt. I can hope now that the thing will go away, burn itself out. All I can do is let that label die.”

There are, anyway, other women in Gary’s life. “Connie,” he says (but only with the greatest reluctance), “still has my ring and my love, but the time for marriage is over The main reason we didn’t get married was that I wasn’t going to be just ‘Mr. Stevens.’ Even now, for all his dates with young singer-actress Pat Woodell, Gary still shies away from talk of marriage. “Pat and I date a lot, and we’re very happy together,” says Gary. “She’s a wonderful singer and a wonderful girl. Pat’s only nineteen, but in her new TV series, ‘Petticoat Junction,’ she’s going to be a big star.

“But marriage now?” Gary shook his head determinedly. “I have no plans—none whatever. Anyway, I do see other girls.”

Or, at least, he used to. Comedienne Kay Stevens, for one, and Austrian actress Maria Perschy for another. In the Universal Studio commissary one day (Revue Productions’ “The Virginian” is filmed on the Universal lot), the blue-eyed Miss Perschy was introduced to a tall, smiling fellow in Western garb. It was Gary Clarke. “He asked me for no less than five dates,” Miss Perschy said later, wonderingly. “I knew TV worked faster than the movies, but I didn’t think there was that much difference in the two!”

Nice to the kids

“Gary,” says his seventeen-year-old brother Mike, “was always a pretty cool cat. All the neighborhood kids looked up to him. He played football with us, taught us magic tricks and comedy diving, and protected us when older boys tried to give us a bad time.

“Why, I still remember the time when Gary was making his first movie, ‘Drag Strip Riot,’ and driving that fancy white Corvette. When the car wasn’t needed in the picture, Gary brought it around and gave all of us younger kids a ride, just so we could get a big thrill.”

But you won’t hear such stories from Gary. What he does regale you with are the kind of wry tales that few actors will tell on themselves.

Still green in Gary’s memory is the night when, fancying himself ripe for Bigger Things, he went over to the Pasadena Playhouse to try out for a new play. He was still Clarke Fredric L’Amoureaux in those days—his real name—and, acting was an ambition he couldn’t quite afford. He earned his real living working behind a turret lathe as a machinist at San Gabriel’s Grimco Machine Shop.

Many a time, when he’d get a chance to read for a part in a little theater play, he’d ask his mother to phone Grimco and say he was sick, or he’d beg a friend to send a wire urging him “to hurry to Montana or Utah where his father had had a terrible car accident.”

“My Dad seemed to have a lot of car smashups,” Gary chuckled, “because I was forever running around trying out for some new play.”

This one night, though, young L’Amoureaux and a friend hustled over to the Pasadena Playhouse after work, where our hero was to read for a part in “Bernadine.”

“I was a pretty cocky kid, then,” Gary smiled, “and I remember I walked up to the director and announced. ‘I’m Clarke L’Amoureaux, and I’m here to read for you.’ ”

Unfortunately, the director was something less than overcome. “Just get yourself a chair, young man,” the director ordered. “We will listen to you in due time.” Unfortunately, too, it was strictly a pro crowd of experienced actors and actresses, as Clarke could see immediately. “Those other people,” he says, “were awfully, awfully good. I got more and more nervous about myself. In fact, I all but fell apart.”

When, finally, it came his turn to read, his voice, he remembers, “went way up in the air like thi-i-ss—it was just a squeak,” and the pitying director could only advise him “to go in the other room and relax. We’ll call you again when we’re ready.”

So Clarke and his friend went into the other room and waited. A half hour passed, then an hour and still another hour. By then it was almost 11 P.M. “Listen,” Clarke told his chum, “go in there and tell those guys I’m ready . . . I’m ready now.”

The memory still breaks him up. “I followed my pal into the rehearsal hall,” he says, “and there was just one lonely light bulb burning. Everything else was dark—there wasn’t a soul around. The director and his staff had forgotten all about me and had all gone home. The next day I dragged myself hack to Grimco, feeling about an inch high. ‘Well, movie star,’ the guys in the shop razzed me, ‘how’d you make out at Pasadena? They sign you up for Hollywood yet?’ ”

Blows like these, says Gary, made him painfully aware that he was still a nobody. “For all too long,” Gary admits, “I seemed to be getting nowhere. My life was just one mediocre day after another. I was getting pushed two steps backward for every one I managed to forge ahead.”

The boy who was to become Gary Clarke grew up on the East Side of Los Angeles, in brawling, gang-ravaged Boyle Heights. It was a sometimes savage area, where roving gangs of rivaling races battled with each other. “You didn’t dare poke your nose into the rumbles that went on around you,” Gary says, “because if you got too inquisitive, you might get your own head shot off.”

There was increasing tension in the L’Amoureaux family, too, and finally a divorce. Ultimately. Mrs. L’Amoureaux and her brood (the younger kids were Pete, Mike and Kathy) migrated to suburban Glendale, where life was a hit better. “Gary was always the family protector.” says young Mike, “until he got married at eighteen and set up housekeeping on his own.” And added responsibilities!

He married too young

The girl was a classmate of Gary’s at high school. Both kids were too young, too unworldly. His parents pleaded with him not to marry, but like so many adolescents, he wasn’t eager for parental advice. “My mother and father hadn’t done too well with their own marriage,” Gary says, “so I couldn’t see how their advice could help me.”

The teen-age marriage broke up after four years of quarrels and recrimination—quarrels that were lacerating to the young couple and bewildering to their three little boys. Gary resolutely declines to discuss his early marriage; his former wife has re-married, and the boys—Jeff, Dennie and David—are happy in then new life, with a stepfather who has given them warmth and security. “I see the boys often,” Gary says, “but for their sake and their mother’s, I’d rather keep that part of my early life out of the public eye.”

“Drag Strip Riot,” a teen-age quickie movie for the drive-in trade, was Clarke Fredric L’Amoureaux’s first real break. It gave him his new name (“I wanted to call myself Jeff Clarke,” he says, “but I discovered there already was an actor by that name”), and it saw the start of Gary’s six-year, often frustrating romance with Connie Stevens. Connie had the feminine lead in “Drag Strip” and went on from there to fame. Gary had infrequent roles in other small-budget films like “How To Make A Monster,” “Date Bait” and “Missile To The Moon,” and went from there to unemployment checks and scrabbling for almost any kind of decent work.

“I took part-time jobs that would leave some time free for studio interviews,” Gary remembers. “I worked in a supermarket for a while. I worked as a door-to-door salesman, peddling pots and pans. All too often there was only the $40 a week I got at the unemployment office, and I’d send $25 of that off to my boys. I worried because I knew this wasn’t nearly enough.”

Bad luck still dogged him for all too long, until there came what seemed to be another break. Gary turned professional singer, with no more real experience than singing in his school choir. “I can’t read music,” he confesses with a wry grin. “I can only tell when the notes go up or down. Actually, my singing career in night clubs got started through a fluke.”

A trio composed of several of Gary’s friends faced a minor crisis when one member got into a fight with a night club stage hand. The bellicose crooner was booted out of the trio; Gary was recommended as a substitute, and made his first professional singing appearance at the Deauville Hotel in Miami Beach. When that stint ended, he soloed with Bill Norvis’s Upstarts at Lake Tahoe’s Wagon Wheel; Hollywood’s Moulin Rouge and at the Stardust in Las Vegas. He also sang in a show starring Louis Prima and Keely Smith at the Desert Inn at Vegas.

“That was my singing year,” Gary says. “It wasn’t exactly what I’d dreamed of. I still wanted to be an actor, but getting up and singing in front of a real live audience—my big number was ‘Mack the Knife’—gave me self-confidence. And,” Gary adds with a grin, “I got a lot of audience reaction of one kind or another.”

As most Las Vegas visitors know, the crowds enjoying the shows at the various night spots are often dotted with lonely, middle-aged females hungry for a bit of “glamour.” One of these women began showing up nightly at a ringside table at the Stardust, applauding vociferously each time Gary sang. Soon the others in the show began ribbing Gary about his “conquest.”

“I really didn’t know what to do,” he confesses. “Now and then I took a drink with the lady, as I did with other customers, or chatted with her as pleasantly and as innocently as I could. But this didn’t seem to be enough. Finally one night, she broke down and cried, saying that if I wouldn’t be her friend, she’d have nothing to live for. ‘Let me love you tonight . . . I’m a very, very wealthy woman’ she said. ‘I have three swimming pools, and if you won’t be nice to me, I can drown myself in any one of them.’

“I was so embarrassed, I said the first thing that popped into my mind. ‘Now, Mrs. X,’ I said, ‘don’t try to drown yourself— you might clog up the drain!’ ”

“I’ll never forget it . . .”

“Sure it was a flip answer. But I was really shook up. Let me tell you something, I will never forget that woman’s desperation and loneliness. You know the saying: ‘I pitied myself because I had no shoes . . . until I met a man who had no feet.’ Every time I start pitying myself, I remember that woman. She owned expensive shoes, but she had no feet to stand on. I’ll never let that happen to me.”

Back in Hollywood, Gary signed for a role in the “Michael Shayne” TV series. Jubilantly he told himself, “At last I’m on my way.” But again he never quite made it.

It seemed to be still another dead end. Most of the time, he recalls ruefully, he was “merely emptying wastebaskets,” or murmuring deathless lines like, “Well. Mike, what do you want me to do next?”

“Yet, as rough a time as I had on ‘Shayne,’ ” says Gary, “it did push me farther along the road. I made some progress, and I learned. Even from the dead ends, the mistakes, the goofs and the hangups that you have, you learn. You learn something and you retain it, and you draw from it later.”

Ironically, the people who brushed Gary Clarke aside, or talked of Connie Stevens marrying him “when his career got going a bit better,” were unaware that Revue Productions signed him to a non-exclusive contract as long ago as March, 1961. Gary was more than “just a nobody,” or the fellow sailing along in Connie Stevens’ light. There were “Wagon Train,” “Laramie,” and “Wells Fargo” episodes in which Gary appeared, and he was chosen for the role of “Steve” in the ninety-minute, big-budgeted “The Virginian” against a dozen better-known names.

“I feel that I’m a very competent actor, a good actor,” Gary says earnestly. “I know I have miles to go, but I do have something to offer, if I can just get a chance to bring out what’s inside. Sometimes, even on ‘The Virginian,’ I get a little bugged, because I seem to be doing little more than tagging along after the show’s bigger stars. But you can’t let things like that get you down, or you’re dead. Last year there were only two stories revolving around me, this year, I hope there’ll be more.”

There is also his Decca recording contract—the platters he is waxing “to extend his range.” Yet nobody can say, even now, that Gary really has it made. There are, of course, more and more letters like the one from the young North Carolina fan who wrote, “I watch you every Wednesday night, and I dream of you twice a month.” But so far, neither Town and Country nor Better Homes and Gardens is about to titillate their millions of readers with a photographic visit to the Gary Clarke pad. If this is neglect or indifference (actually, it isn’t) , it is a condition that Gary faces with a smile of equanimity. And if Gary’s somewhat nondescript, two-bedroom house is not yet featured on those Movie Stars’ Maps—well, Gary figures, that’s the way the ball bounces. For one thing, his house is all but impossible to find, hidden away as it is in a narrow, graveled cul de-sac in the not too fashionable hills off Mulholland Drive. It is also, as Gary quips, as untidy and cluttered as most bachelor pads.

“Well, now,” Gary chuckles, “everything in this place is authentic Early Salvation Army. You see this old oak chair I m sitting in? Steve Ihnat—that’s my buddy who shares this house with me—picked it up in the back room of a used furniture store for seven dollars. That huge desk with forged iron hinges that looks like a pirate’s chest was donated to us. And that fumed oak dinette set in the hall—our treasure—was practically stolen from the Salvation Army for ten bucks. Man, Steve and I were like a couple of bandits when we went out scouting around to furnish this place of ours.”

He lugs his own laundry

Of course, there is still that $5,000 Italian-styled Avanti sports car sitting at the top of Gary’s steep driveway, but he also uses the jet-black speedster for picking up his weekly laundry. The Avanti seems to be Gary’s only present concession to the glamorous Filmtown life. (“I hate those Hollywood parties,” Gary says, “where some guy will pound you on the chest and say, ‘First, let me tell you about my pictures, before you talk about yours.’ ”) Inside Gary’s living room, the bookshelves share space with childhood encyclopedias, a hi-fi rig, a portable TV set. an ancient folding camera at least fifty years old. and an accumulation of books ranging from Stanislavski’s erudite “To The Actor,” to a rain-battered copy of “The Rover Boys And Their Electric Submarine.”

But the startled visitor, most of all, is captivated by two unexpected sights: that antlered and bearded head of the wild goat hanging above the fireplace, with those sunglasses shading its eyes and the cigarette dangling from its mouth, and a battered portable typewriter on the coffee table, holding the half-completed page of a TV script.

The goat, Gary admits, almost cost him an eye when the big, high-powered gun he was shooting recoiled, splitting his forehead and giving him a still visible scar. And the partially completed script in the typewriter?

“I’m writing a teleplay for ‘The Virginian,’ ” Gary says. “The only reason I’m doing it is the scarcity of good Gary Clarke parts. I think it’s a helluva story, and I hope Revue will buy it from me—if I can twist their arm.”

Well, as a script writer Gary may be a far better actor. But there are steadily increasing signs that the gears are beginning to mesh for The Kid from Boyle Heights. Gary’s new personal manager is Bob Marcucci, famed for his spotting of 24-carat talent and the development of a couple of boys named Fabian and Frank Avalon.

What is Marcucci doing for Gary? “Why,” says Gary, in a comedy gung-gung voice. “He’s gonna make me a big staarrr! Seriously, though, Bob and I are going to map out a goal and aim for it. He thinks I should be ready for feature pictures—for real big things. Anyway, I’m putting myself in his hands. He’s already helped me a lot, and I feel he’s going to do more.” He may kid, but he puts a lot of faith in his manager.

That Label, though: that’s something that Gary will have to erase himself—just by being himself. Gary’s friends at Revue are betting that he will. “This is a pretty strong guy in his own right,” these friends say. “He’s no appendage to anybody. Maybe he has to learn how to assert himself more, or forget his awe of people. But Gary’s a real one—don’t think he isn’t. He never once complained when things were going badly; he just took all those tough knocks and went right on.”

Eventually—probably even now—Gary’s salvation will be his deep-held faith that “There’s all kinds of room at the top.” “You don’t have to knife anybody to make it,” he says. “Nobody on earth is quite like you, so you have a chance to get there as well as the next guy. That’s what I believe . . . that’s what has kept me going . . . that’s what I’ll always believe.”

THE END

—BY FAVIUS FRIEDMAN

See Gary on “The Virginian,” via NBCTV, Wednesdays 7:30-9:00 P.M., EDT.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1963

No Comments