If You Like What You Love You’re In Luck—Doris Day

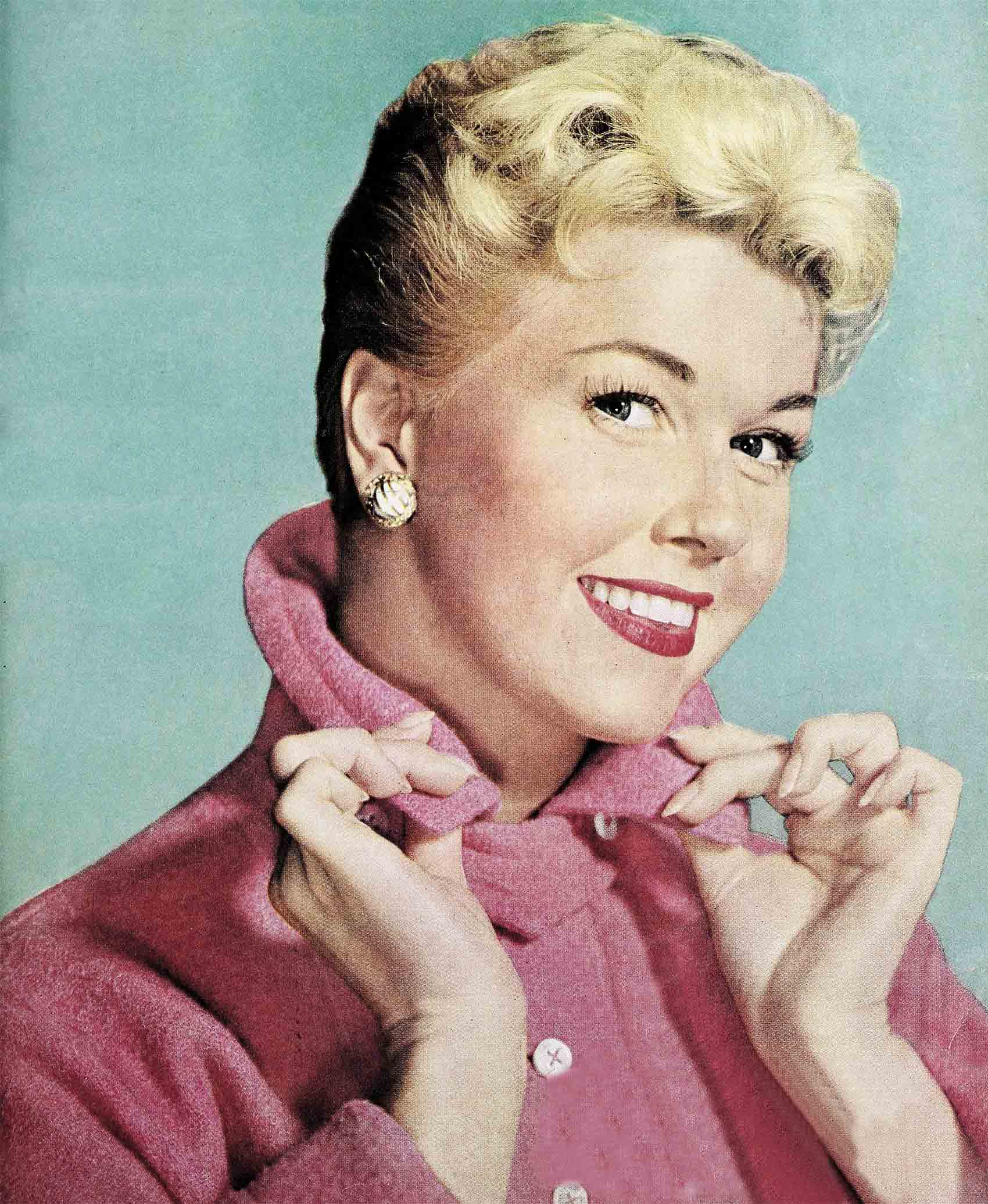

Much has been written about Doris Day’s charm, her brightness, her radiance. There is nothing to question. It’s really there: the shiny blond hair, the clean looks, the sparkling blue eyes and, of course, the smile—a terrific smile, wide, warm, utterly disarming.

The place on the Warner Brothers lot where the stars and the executives eat lunch is called the Green Room. It looked pretty drab until the moment Miss Day, followed by Marty Melcher, came through the door. She brightened the whole room. There’s an electric quality about this girl. She gives off sparks. You know, when you meet someone like Doris Day, that you’re meeting a personality; that you’re in the presence of a star. But a comfortable, down-to-earth sort of star.

“I’m hungry,” Miss Day said, sitting down and looking over the menu. Miss Day has a reputation for being hungry. “I think I’ll have the steak.”

“Me, too. And I’m having French fries with it,” Marty announced belligerently. “I did twenty laps in the pool this morning. I’m trying to take off a few pounds and it’s murder!”

Marty—Marty Melcher—is Doris’ husband. He’s also her agent, business partner and sometime boss when he’s producing one of her pictures. He’s also known to be her tower of strength.

What was the secret of their success in marriage? I asked.

“It’s very simple,” Marty answered. “Half the time I let Doris have her way; the rest of the time I give in.”

“Don’t let him kid you,” Doris bristled good-naturedly. “Between my two men at home I don’t stand a chance. They gang up on me and lead me around by the nose. I’m always the one who loses.”

“Marty is the voice of authority at home,” Doris explained. “Terry is crazy about him. Sometimes I think that’s why Marty married me.”

“Don’t forget Nana,” Mr. Melcher objected.

“Nana is my mother,” Doris explained, “and Marty dearly loves her.

“You see, I’m just an ‘also-ran’ at home,” Doris said. “I don’t count much.”

“Not much. You should see her do her gardening.”

“I like gardening, but I need a little help,” Doris admitted.

‘Doris reminds me of a surgeon,” Marty explained. “Scalpel—sutures—scissors! With Doris it’s: ‘hoe—shovel—sprinkler!’ ”

The steaks arrived, sans potatoes for Mr. Melcher. “Let me at least try one,” he said, spearing several off my plate. Miss Day mixed her tomato juice with a glass of buttermilk, admiring the pink hue she’d concocted. “It’s delicious. Try it,” she said, offering me her glass.

I took a sip while Marty, having followed suit mixing the brew, downed half his glass at one swallow. Like taking medicine. I nevertheless wasn’t quite ready to extend him my sympathy. “Tell me,” I asked. “Does she leave the cap off her toothpaste?”

“Invariably.”

“That’s only the half of it,” Doris conceded cheerfully. “I’m a tube wrestler. I can’t help myself. I squeeze them all out of shape.”

“And when she’s through with hers she starts in on mine,” Marty observed.

As husband to husband, I was beginning to feel an affinity with Marty Melcher. “What about late snacks?” I asked.

“No problem,” Marty said. “I have troubles, though.”

“I make him jumpy at times when I rehearse my lines,” Doris elaborated. “I always do before I go to sleep.”

“I’m peacefully dozing off and she’ll suddenly shout: ‘I’m going to have you arrested, you cad,’ or something like that. It’s enough to make a nervous wreck out of anyone.”

“Never mind,” Doris said. “You get even with me when I’m having my massage. I get all relaxed, feeling wonderful. Suddenly there’s a scream. ‘Shut up. Don’t make a move,’ someone says. ‘What’s the matter, darling?’ I shriek. No answer. Then—‘Get into that coffin, sister,’ the same voice. By that time I finally realize it’s the television. It’s the one time when I can’t stand television.”

“You see,” Marty said. “It’s not always so easy being married to Doris.”

“Anyway,” I said, “you can have Doris’ singing whenever you want it.”

“What do you mean?” Doris protested. “Marty does all the singing at home—in the shower.”

“I sing pretty good,” Marty said, somewhat injured.

“A great voice,” Doris affirmed. “My gain was the Met’s loss. Marty dances, too. Clad in a bath towel.”

Several people stopped at the table to say “hello.” Doris Day incorporated greeted them with her customary charm. You could see them brightening up, literally like a darkened room whose shutters are suddenly thrown open to the sunshine and daylight.

“They’re nice,” Doris said after the visitors left.

“Doris thinks everybody should be happy,” Marty commented. “Or at least to try to be happy—think happy thoughts. She’s right, too. It’s one of the things I’ve learned from her and I’m grateful for it.”

“What’s the use of making yourself get depressed? The whole world would be a happier place if everybody tried harder to think only in positive terms. This is not just a line. I’m convinced of it. It’s worked pretty well for me. It can work for others, too. I like things that are nice, wholesome.

“I’ll have banana cream pie for dessert,” Doris told the waitress.

“Coffee for me, black,” Marty ordered balefully. “Look at that girl—banana cream pie—and she doesn’t gain an ounce.” Doris looked slim and trim in a sky blue, pleated all-around shirtwaist dress with pleated cap sleeves and collar.

“I work hard—I’ve got to eat,” Doris said, putting her fork in position for that first, delicious bite.

What, incidentally, was she doing when she was not working? I asked.

“Rearranging furniture,” Marty answered. “Sometimes I come home at night and I think I’m in the wrong house. It’s a good thing we’re not living in an apartment. I’d really be in trouble.”

“It’s a good thing you’re not a drinking man,” Doris added gaily.

“You can see it’s not so easy,” Marty said again. “Come see me alone some day and I’ll give you the lowdown on our marriage problems.”

“You do that,” Doris encouraged me. “And come see me later. I may have something to say on that, too.”

I had a warm glow taking leave of Doris and Marty, the kind one always feels after meeting a couple who are happy and in love. For underneath the kidding and the banter that was quite obvious, they’re congenial, enjoy each other’s company, and there’s genuine trust, friendship and affection between them. They like each other. Which is even more than being in love.

It’s easy to see why they should be attracted one to the other. Doris and Marty are a study in contrasts, a composition in black and white. Marty—a good deal handsomer than he appears in snapshots—is very dark, the perfect foil for Doris’ fairness. Where Doris is bubbling over with enthusiasm, is straightforward and direct, Marty is wry, suave, very calm and restrained. Such differences frequently generate the spark of attraction.

However, the Melchers have now been together for close to four years, and from the looks of it they’re going to stay married till the end of their lives. What was it that seemed to tie them together so securely?

The Marty Melcher I met alone in his office was different from the urbane man he’d been at the luncheon table.

“We love each other,” he said simply. “Doris is a wonderful girl. She has—how shall I put it?—she has confidence. Not just confidence in herself; a lot of people have that. Doris has confidence in life. It’s more than faith, she has that, too, very strong faith—it’s a deep instinctive confidence that life is wonderful and that everything that happens is for the best. It’s a sense of belonging, of being right and fitting for this world. I admire her for it, and I envy it.

“Sometimes I think of her as Pippa,” Marty smiled. “You know, Browning’s poem, ‘Pippa Passes’? When I look at Doris I know that all’s right with the world.”

“Incidentally, how is Doris in the morning?” I asked.

“Sleepy, but cheerful after she’s had her breakfast. You’ll never see her grumpy.

“That’s the miracle about this girl. Doris has actually had more than her share of setbacks and heartbreak in her life. You probably know that she nearly was crippled in an automobile accident when she was just a kid. It took her over a year to get back on her feet and cut short a promising career as a dancer. She took up singing only as an afterthought. She saw her parents divorce, was married herself by the time she was eighteen and had Terry to take care of and make a living for at an age when most girls are just beginning to take their first, shy look at life.

“Most people. would have become sour and hard with the kind of tough sledding Doris had, but not she. Believe me, that sunny disposition is no pose. I don’t think there’s anything that could take away her joy of living for very long.

“Don’t make the mistake of thinking that Doris is not sensitive or doesn’t feel very deeply, though. She’s a warmhearted girl whose grief can be as poignant as that of any other human being. That’s part of Doris’ make-up and part of her charm. She feels intensely, and she’ll give all of herself. She’ll never hide part of herself under a mask. You always know where you stand with Doris.

“Another thing is, she’ll grieve, but she won’t brood. Sooner or later her natural buoyancy always breaks through. She’s quite a girl.”

Marty’s and Doris’ own romance started slowly, blossoming into love through mutual trust, friendship and understanding. The first evening they spent together was following a recording session to which Marty had taken Doris reluctantly to help out his partner, Al Levy, who was then Doris’ agent. Neither of them was in a mood for romance.

They found they liked each other’s company, though, and pretty soon Marty got into the habit of dropping by Doris’ home and having dinner with the family. Terry, Doris’ son, seemed to take a shine to Marty immediately. Marty has since adopted him and feels not in the least like a stepfather.

Marty and Doris were married on Doris’ birthday, April 3, 1950. Doris’ mother had to shoo them out of the house for their honeymoon. They made it brief. Both were longing to settle down with each other. At long last they’d found peace.

Peace—with all her exuberance and all her success—wasn’t one of the things Miss Day had an oversupply of before her marriage to Marty Melcher. A trooper since her teens, she’d been on the move almost constantly, leading a restless though frequently exciting life. Even before her near-fatal automobile accident at the age of fifteen she’d played a series of summer bookings, teaming up with her school chum Jerry Doherty in a kids’ comedy dance routine. She expected to do big things as a dancer, but the accident at a railroad crossing in a car crowded with youngsters shattered those dreams. The year she spent in a plaster cast trying to get well and back on her feet wasn’t exactly a peaceful one either. For a long time it looked as though she’d never walk again except on crutches, or at best only with a bad limp. The idea of becoming a dancer, of ever again expressing with her feet the rhythm she’d felt in her blood since she was a baby seemed definitely out. But Doris, a born performer, was irrepressible. If she couldn’t dance, she’d sing.

At first she only sang for her own pleasure to give an outlet to the exuberance and rhythm that bubbled up again despite the setback. Then a frend of her mother’s who happened to be a singing teacher took her in hand and worked on her range. Fourteen months after her accident, still hobbling on crutches, she was back in business at the old stand, the local dances in her home town of Cincinnati, Ohio. But where she’d once hoofed, she now sang, and sang well enough to attract the attention of professionals. A song plugger, Danny Engel, recommended her to radio station WLW’s voice coach, Grace Raine, who in turn recommended her to Barney Rapp who was looking for a singer for his band.

“I can’t use that name,” Rapp said when he was told about Doris Kappellhoff. “But send over the girl. Maybe I can use her.”

Doris sang for him “Day After Day,” was hired on the spot and changed her name to “Day” after the lucky song.

Doris was mighty happy over that first break; but she couldn’t stand still; she had to move on. Always on the go, she went from Barney Rapp to Bob Crosby, and finally to Les Brown. Then came a ballad, “Sentimental Journey,” that sold over a million platters and spread her fame from coast to coast. The next step was a successful screen test for Mike Curtiz, a starring role in “Romance on the High Seas,” and a Warners contract.

Success came to Doris fast after that, but happiness still eluded her. Mom and Terry moved out to Hollywood at last and she found a great measure of contentment, yet perhaps without being fully conscious of it herself, she felt incomplete not being married. The famous grin came back pretty quickly, and the exuberance, but the inner glow was added only when Marty Melcher entered her life.

“Marty is a very kind person. That’s what I love perhaps most in him,” Doris told me when she, in turn, spoke to me alone. “At times he’ll make a pretense of being cynical, but underneath it he’s one of the softest, gentlest men I’ve ever known.”

Doris needs kindness, always has needed it. Even as a child, she often used to wake up crying, plagued by nightmares and evil phantasies conjured up by the dark. When she ran into her parents’ bedroom for reassurance her father would send her away. “Doke,” he’d say. “You go back to bed. And let’s have no more of this nonsense.” Then she’d stand shivering in the hall, waiting for her mother to come tiptoeing out and comfort her in her arms.

“Terry knew Marty was all right the minute he laid eyes on him,” Doris continued. “Kids seem to have an instinct for that sort of thing. Marty is a wonderful father to Terry—and a wonderful husband to me.

“Sure I was in love before. I knew heartache and misery and thought that was the way it had to be and always was. I was wrong. Since I’ve known Marty I’ve learned that love really is the most beautiful experience two people can share.

“It takes a little growing up. This isn’t kid stuff. But most of all you have to be lucky and find a guy who’s good, patient and sweet, a guy who’ll never hurt you; someone who cares about your welfare and happiness as much as he does about his own, and you about his. Never mind all this talk about friendship, security, understanding. In my book, that’s love.”

THE END

—BY ERNST JACOBI

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1955

No Comments