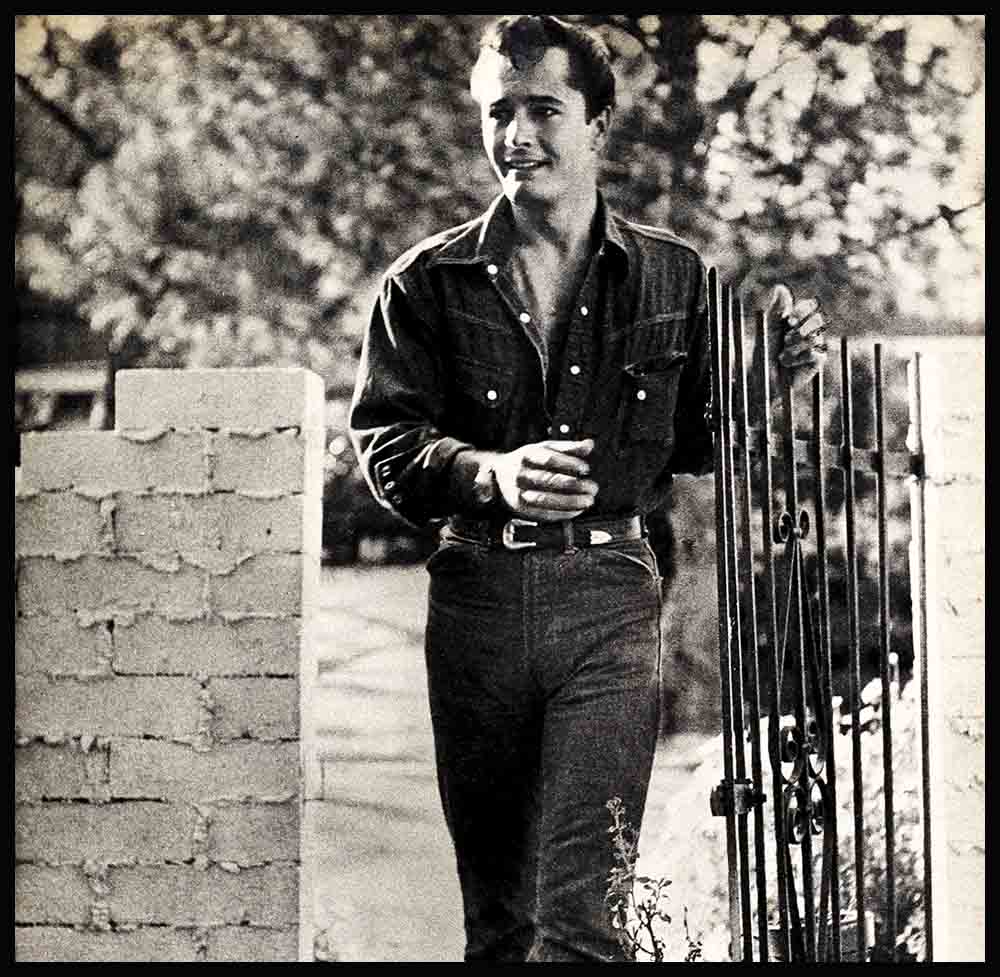

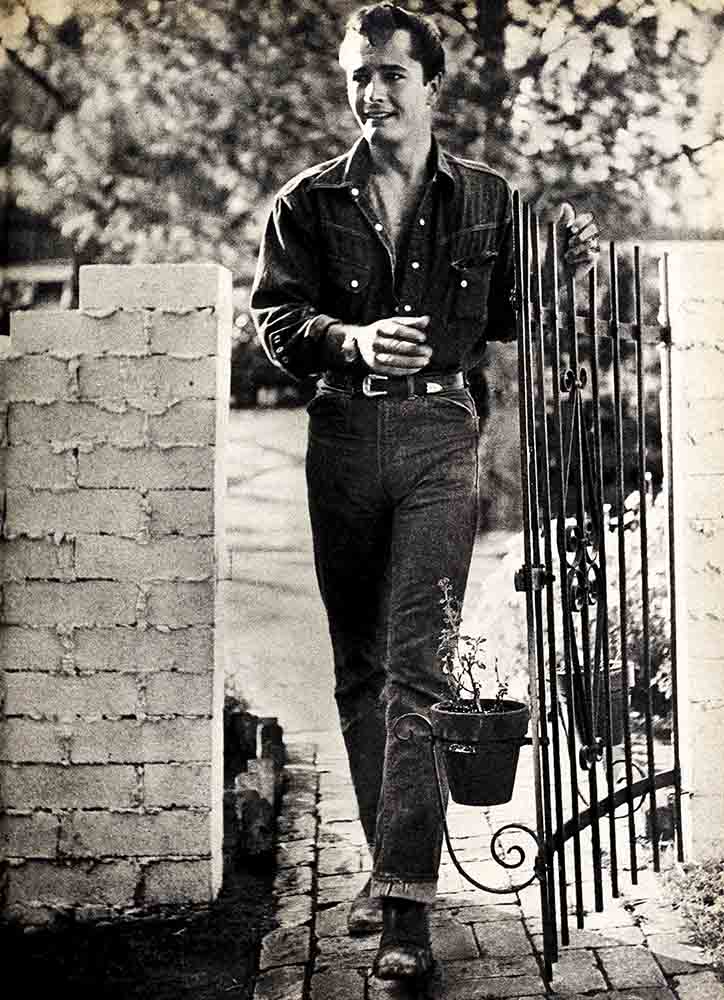

Is Hollywood Destroying John Derek?

The other day, on the set of “Posse,” John Derek was introduced to a visiting family from Nebraska. The woman shook his hand, and with a faraway look in her eyes, said, “My, you must lead a wonderful life!” The man slapped him on the back and said, “Some gravy train, son! What’s it like when everything you touch turns to gold?” And their daughter just looked at him and said, “Gee!”

John himself merely smiled politely. He couldn’t tell his visitors what he really felt—how he’s been in a tailspin lately—how, more than once in the last couple of years, he’s been tempted to pack his bags, take his family, and head out for somewhere—anywhere—a million miles away from Hollywood.

For Hollywood, whether by intent or by chance, has seemed to be giving him a brush-off.

He started out with a bang in “Knock on Any Door.” But the majority of the pictures he’s worked in since have been run of the mill. John’s unhappy about it, and he doesn’t care who knows it. He says very frankly that he has had too many bad pictures and not nearly enough money.

And it certainly isn’t for lack of appeal. For John’s fans refuse to forget him. They keep bombarding Photoplay, for instance, with irate letters asking why they can’t see him more often and in meatier roles. But the answer to that question is an involved one, tied up with John’s whole career.

The story goes something like this:

John first played a small role for David Selznick, in “I’ll Be Seeing You” with Shirley Temple. But when Selznick released his players, John was on his own. And he found the going tough.

Then, one day, he heard through the grapevine that Humphrey Bogart was going to make “Knock on Any Door.” He read the book, and then, somehow, managed to wangle a script. One reading was all it took. He knew he was right for the leading part—Nick, the “pretty” juvenile delinquent. But getting to Bogey to prove it, was something else again. John tried all the routine methods—the polite phone calls, the carefully-phrased letters. He tried every “proper channel” in the book. And when nothing else worked, he finally took the bull by the horns and literally forced himself into the star’s office. And then, though he was horrified by his own audacity, he made Bogey listen to him.

How well that worked is ancient history by now. He got the part, was a tremendous hit, and, as a result, wound up with a seven-year contract. That was back in 1948, and nothing could stop him after that. He thought! But he was soon to learn disappointment—Hollywood style.

Following his initial splash, he was given some distinctly mediocre roles. The first sign that the jinx might be breaking came when he was loaned to Robert Rossen, the independent producer, who wanted him for “All the King’s Men.” The film won the Academy Award for 1949, and John himself was dubbed as a sure comer. “Keep your eye on Derek!” was the good word around Hollywood.

John earned more while he was working on “All the King’s Men” than he ever had before—a reported $1,500 a week. His salary on his home lot was peanuts by comparison, and he felt, with what seems justifiable logic, that if he was worth that much to an outside producer, he should have been worth at least as much to his own studio.

Not long after that, Alfred Hitchcock wanted to borrow John for a role in “Strangers on a Train,” the picture that won raves for Robert Walker and Farley Granger. But the studio refused. And John, seeing the chance for a “hit” performance snatched out of his fingers, was truly nettled. But that did him no good at all.

Nor did it do him any good to gripe last year when Paramount, on learning that Alan Ladd was leaving its roster, offered to buy John’s contract at a fabulous figure. John could, Paramount felt, very capably have filled Alan’s shoes on the lot.

But the studio remained adamant to all requests to let John work for somebody else—until last year, when he made “Thunderbirds” for Republic, the movie John thinks is his best since “Saturday’s Hero.” And now, at last, things look great on his home lot.

There’s hope—great hope, John feels, in the fact that after having cast him in two adventure yarns, “The Prince of Pirates” and “Posse,” his studio seems to be giving him a chance again to prove himself effectively in his latest assignment, co-star with John Hodiak in “Mission Over Korea.”

John Derek has never been considered a particularly light-hearted guy. He is serious about his life, his career, his marriage, even his morning egg. But the talk around Hollywood these days says that, even for the serious-minded character he’s always been, John is a pretty gloomy Gus. And there are some who’ll try to tell you that his career problems are only a small part of the trouble.

Certainly, the illness of his small son, Russell, has been a factor. No parent could have survived this ordeal and emerged unscathed. Russell was born with a faulty esophagus, and there were repeated operations, and many, many months of patient care—and heartbreak—before he was out of danger. Even today, the Dereks keep emergency equipment handy at home, in case Russell should have a relapse.

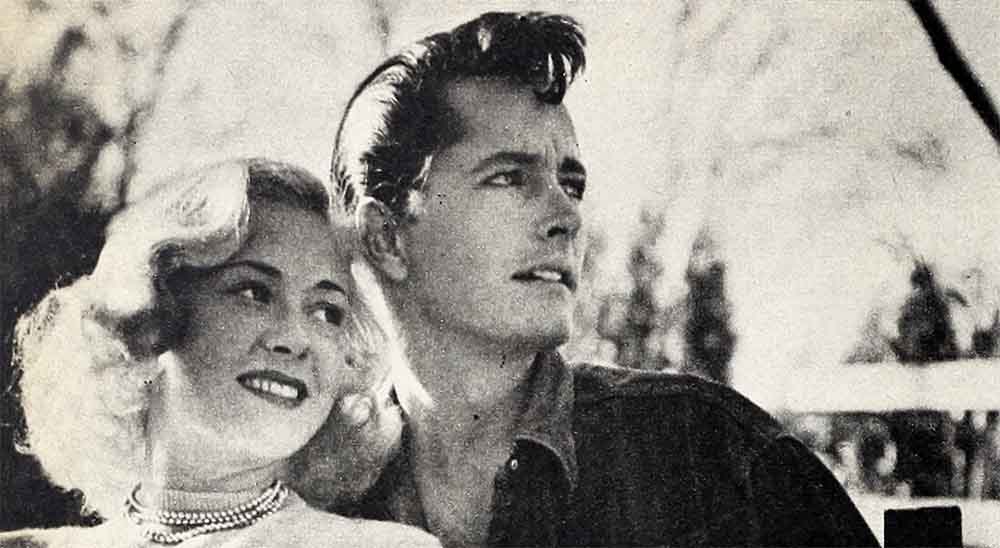

There have been the usual rumors, too, about John’s marriage—that it has failed or will fail. Pati Behrs, John’s wife, is an authentic Georgian princess who came to America not many years ago and started a career as a professional dancer. She was as ambitious as the average young girl in show business, but she met John before she had her career really going full-swing. She had had only one movie role, a bit for Twentieth Century-Fox, by the time they were married in 1948. And then she immediately settled into domesticity.

Some Hollywood crepe-hangers say that’s the trouble—that she had just enough taste for a career to whet her appetite for more, and that now she resents having given it all up, and that the resentment shows up in her attitude toward John.

One Hollywood writer—female—puts it this way:

“Pati is an attractive girl, but she doesn’t do anything to emphasize the fact. She’s always lolling around in blue jeans, and I can’t remember when I’ve seen her in a full make-up job. She doesn’t look like a movie star’s wife should look. It’s almost as though she were backsliding on purpose.”

And a Hollywood photographer says: “Pati doesn’t do anything to build up John’s ego. And he needs it. He’s so self-conscious about his remarkable good looks that he does everything he can think of to prove his masculinity. A guy like that needs self-confidence, and the best place to get it is from his wife.”

But one of the Dereks’ best friends—a chap who has known them both intimately for years—gets violently angry when he hears remarks of this sort. “They’re wasting their breath when they gossip about this pair. John and Pati are very much in love. And there’s never been any trouble between them. My money’s on their marriage lasting longer than any in town.

“Sure, John needs self-confidence,” he goes on. “But the only way for him to get it is for Hollywood to give him the break he deserves. He’s earned the right to prove his place as an actor—and, incidentally, to build up his bank account!”

John’s finances have been stretched at the seams since he bought his home in Encino. At this writing, his salary is less than $1,000 a week, a figure which is gigantic compared to his earnings in the past. Only a year ago, he was getting $500—and that came only after a long series of tiny raises. Compared to other young stars’ salaries, John’s is not bad, but his expenses are unusual.

Out of his salary, John has to pay heavy taxes, to meet the mortgage installments on his house, to pay his agent, a business manager and a press agent, besides taking care of the regular living expenses for his family and the upkeep on his property. And that’s a lot tougher to do than it is to list it on this piece of paper. Besides, John has had a number of crushing bills for Russell’s operations and medical care.

Of course, people will say, “It’s his own fault if John saddled himself with debts beyond his means.” And nobody can argue that point. Nor can anyone argue that John wasn’t lucky to get such a head start on his career in the first place. But almost anybody who knows anything at all about Hollywood will agree that John is constantly facing tough financial problems.

So luxuries are deleted from the Derek budget. Completely. John has wanted to own a horse for years, but he can’t afford one; the one he keeps is not his own. It is impossible for the Dereks to entertain—even on a small scale, so they sit home night after night. Of course, it’s dull and depressing. Who wouldn’t find it so?

People are wondering when John will snap out of it. But he can’t—not if things remain as they are.

John is in a rut at the moment which would unbalance many stars who know less about Hollywood and its industry than he does. John was born and grew up in Hollywood, and so he has not been surprised by the hurdles set in his path.

He has not gone Hollywood in any sense of the word, a fact which, in the long run, is far more important than a dozen mortgages or a million bad pictures. He has done the most vital thing of all: he has kept his head. And that will no doubt see him through.

There’s every indication that the next time that family from Nebraska comes to call, he’ll be able to answer them in no uncertain words. “Yes,” he’ll probably say. “It is a wonderful life!” But he may add in an undertone, that it took a lot of dogged patience to make it so.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1953

No Comments