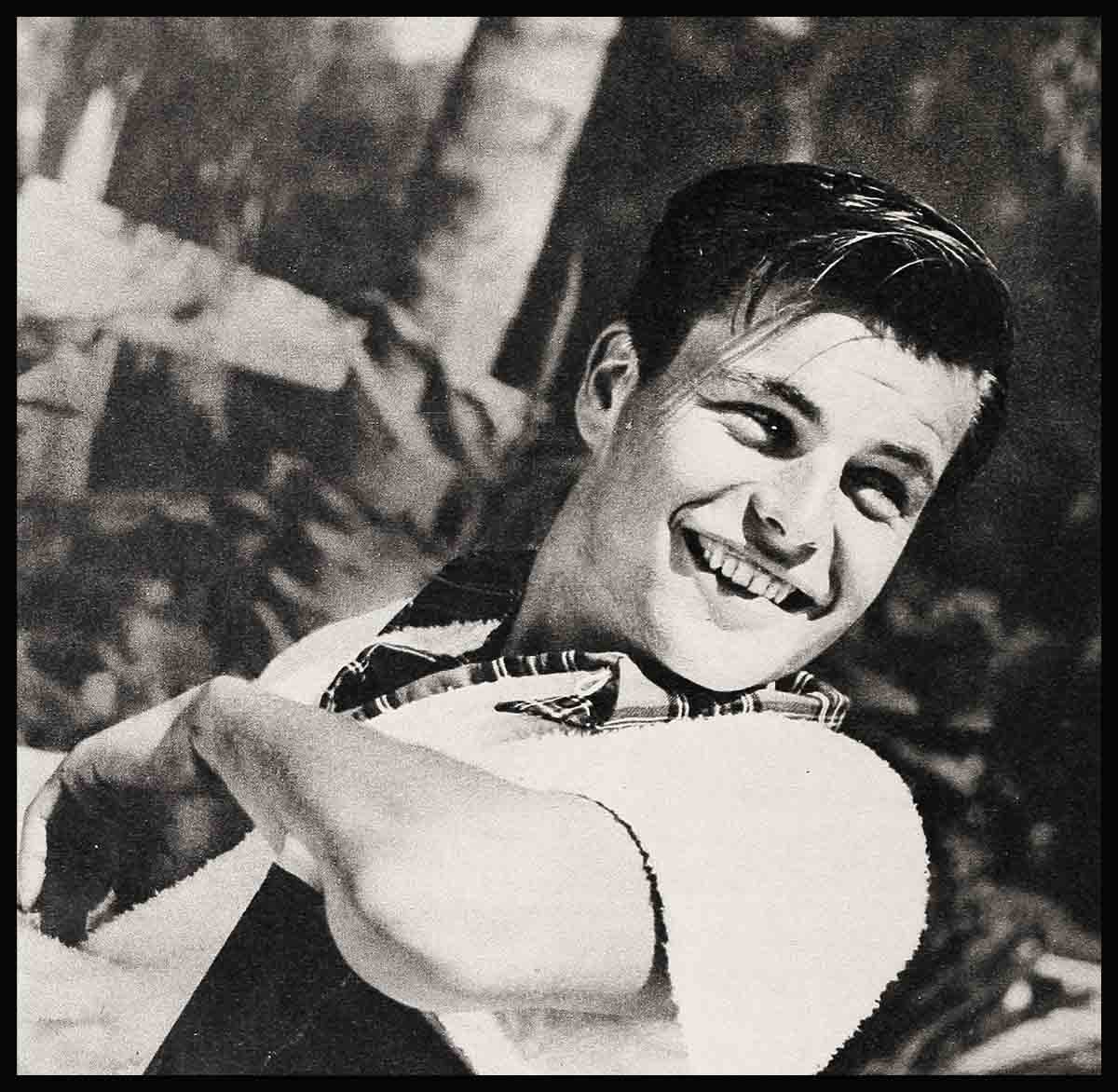

Can He Live Down His Past?—Robert Wagner

To all appearances, it seemed no problem at all—this business of breaking into motion pictures. For young R. J. Wagner, it involved no more effort than that of dropping by a Beverly Hills restaurant where a fellow he knew played the piano. As it happened, agent Henry Willson, star-builder deluxe, was there and found himself neglecting his dinner to watch the Wagner facial expressions as Bob listened to the music. Through a mutual acquaintance, Henry was introduced. A day or so later, Bob and his father visited the Famous Artists’ Agency to talk business with Mr. Willson. And not long after that, Bob was signed to a Twentieth Century-Fox contract.

Of course, a bit of luck is required—being in the right place at the right time, for instance. But it all comes easily, the wiseacres will tell you, when you have a past like Bob Wagner’s—when you come from a well-to-do family and have the right contacts. And consequently, from the first day Bob walked into Twentieth’s commissary dressed in levis, looking like Hollywood’s answer to Huckleberry Finn, the wiseacres have turned on him a slightly suspicious eye. “What,” they asked themselves, “is he trying to prove?”

In the successive weeks as his levi-ed person was seen on the lot every day, they kept asking, “Now why the eager beaver masquerade?”

There he was—a young, handsome boy who’d never suffered or starved for his art, and that in itself was a little unforgivable to those born with greasepaint in their veins. The more practical-minded found it incomprehensible that he would turn down a brilliant future in the steel business to try his hand at acting. And while a studio contract entitles any embryo actor to the standard equipment and attention on the lot, he has to earn that extra lick—the one that can mean the difference between supporting player and star. No grizzled grip or gaffer, long immune to the glamour of the trade, is to be influenced by a bankroll background, a princely physique, or a grey eye loaded with languishing appeal.

When Bob entered the acting profession, even his family and friends were prone to look on with a tolerance and amusement. William Wellman had given him his first role in “The Happy Years” with Dean Stockwell at M-G-M. It was a one-line part. Bob played a catcher in a ball game. He wore a funny suit with a high collar and sported a very stiff expression on his face. Nevertheless, an excited Bob Wagner and his mother attended the Westwood preview. Then, when his big close-up came on the screen, Bob discovered that two girls he had known all his life were sitting behind him in the theatre. “There’s R.J.,” they chortled, nearly rolling in the—aisles.

They didn’t add, “Well, what a lark!” But the meaning seemed to be there. And Bob had to face facts. He was going to have to prove, not only to friends, but more importantly to technicians, producers, directors, other actors and laborers, that for him, acting was no summer inspiration. That he wasn’t a playboy, playing a game until the shine wore thin.

Becoming an actor was no sudden whim on Bob’s part. True, at one time he had prepared for the steel business fairly thoroughly. He made a detailed study of steel and its alloys in school. When he was eighteen, he spent a summer in the steel mills in the East, “learning the whole process from ore to furnace.” Later, he went to work for his father as a salesman for $200 a month, “and we were to divide the profits at the end of the year.”

During the time he worked, he was a whiz at selling steel. But his heart wasn’t in it. His heart was inside the walls of the motion picture studios he passed daily driving back and forth. Finally he told his father, “This I’ve got to try. Will you back me for one year?”

Although he agreed, his father wasn’t entirely happy about the project. “He wanted me to stay in the steel business,” Bob remembers. “And besides, even Dad thought I might not be really serious.”

Once his dad was convinced, he wanted something to happen for his son. That is when he talked to his friend, Director William Wellman. “The Kid’s interested,” he said, “What would you advise?”

Wellman replied that he would give Bob a part in “The Happy Years.” It was a beginning. Contacts can open the right door—but without the right measurements for stardom, once inside, you can find the way a hall of mirrors, going nowhere except eventually back outside again. Now, at Twentieth, Bob is out to show that he’s inside for keeps.

As people work with Bob, they begin to discover that his interest is no masquerade. His natural, friendly warmth helps weaken the psychological barriers and his honest enthusiasm has a habit of winning over all those so long accustomed to separating the synthetic from the sincere. They find him to be a little shy, almost naive and, instead of conceited, humbly appreciative of any advice given him. They find, as Debbie Reynolds says, “R.J. just never thinks he’s any good. You can try to keep talking him into believing it, but it never works. He’s so down-to-earthy. That’s his great charm. With R.J. it’s no act, either.”

One by one, seasoned troupers have found themselves wanting to help him up the ladder on the long way ahead. He’s eager to learn, willing to work, grateful to be told. “Look, Kid . . .” they say. And Bob looks and listens and learns.

You can’t buy the friends he’s made. Or their deeds of friendship. Take the time Bob was making “Let’s Make It Legal.” He had one particularly tough scene . . . one that required some forty-nine “takes.” He was supposed to mix martinis, quarrel lengthily with Barbara Bates and finally stalk out of the room. It was a tight scene with four pages of script and a lot of business. It was rough trying to remember where to hit the mark and all the rest. When the cameramen seemed to be reloading a lot—he didn’t know until later—they were covering him. Doing the scene over and over, he become more and more nervous. He knew when the forty-eighth “take” came that it still wasn’t his best. “Want to do one more? What do you think?” the director asked.

Bob hesitated. “What’s the use? I’ll never be able to cut it,” he was thinking. Then, from the catwalk high overhead a hoarse voice floated down. “Come on now, gang! Let the Kid try it again,” it said.

The Kid, touched and encouraged, tried again. And that was the scene you saw.

While making “The Frogmen,” he again found help just when he needed it most. They were shooting on the deck of a destroyer escort—another tight set with no room to move about. Bob kept overstepping his mark. Finally he heard somebody yell, “Hold it!”

A gaffer had purposely blown a light. The small delay gave Bob a chance to gauge the mark and regain his confidence.

Actors like Richard Widmark have gone out of their way to show him how to make a bit stand out on the screen. While they were making “The Halls of Montezuma,” Widmark noticed Wagner was getting lost in a scene that called for the Marines to advance under fire up a hill and jump into fox-holes. He was rushing it too much. “Look, Kid,” Widmark said, taking him aside and huddling with him quietly. “When you’re with a bunch of guys the camera can lose you—easy. You can walk right through it and out. Slow down. Take your time. And this time, Kid—follow me . . .”

Says Bob gratefully, “I was between him and the others. I was right behind him all the way, and with the cameras full on me. Dick put that one right in my lap! How can you lose with guys like these behind you?”

Helena Sorrell, studio drama coach, who’s worked with Bob since the first test he made that cinched his contract, and in some sixty other tests he’s made (often to help out other hopefuls, as well as give himself more confidence before the camera) says, “He’s one of the most deserving people I’ve ever known, and one of the hardest workers. He’s worked for everything he’s gotten here.”

Inevitably, the long hours he’s spent on test stages are paying off for him. Particularly one test he made to help out a young starlet whose option was coming up very soon. When he found they were doing a light scene, knowing how important the test was for her future, he was hesitant. He began saying, as he usually begins and keeps saying right up until the cameras roll, “Do you really think I can do this one?”

Later, when executives went to see the girl’s test, they were amazed by Bob Wagner’s performance. “We didn’t know he could play comedy,” they kept repeating one after the other, and a few days later he was announced for the romantic lead in “Stars and Stripes Forever.”

John Ford, while running a number of those tests, was so impressed by Bob’s performance in one that he gave him the part of the young private whose poignant love scenes with Marisa Pavan are now winning him more fans in “What Price Glory.”

“Wagner? I think he has a great future. He’s going after the business right. And he listens. . . .” Director Walter Lang is quick to say.

When Producer Lamar Trotti and Lang told him, “There’s a real wonderful bit in ‘With a Song in My Heart’ that will do a lot for you—really get you started in the industry as an actor,” Bob didn’t count the lines of dialogue, but gratefully took their word. His portrayal of the shellshocked young paratrooper is a heart-warmer to remember.

These people are only a few who have no inclination to doubt his earnestness when Bob Wagner sits down with a script.

Despite anything cynics might mutter to the contrary, Bob has had from childhood a healthy respect for hard work and the value of a dollar earned. “My dad’s the kind of guy—if I wanted a fifty dollar bicycle, he’d say, ‘Okay, you raise twenty-five dollars of it and I’ll put up the other twenty-five dollars.’ ”

When he had to come up with his half of $600 for a car, it took a whole summer vacation, and an assorted number of jobs. He even worked as a dishwasher at the Bel Air Hotel. “But that didn’t last long,” Bob grins. “I came in late one morning and the chef fired me. He works in a Beverly Hills restaurant today and we laugh about it. We’re friends now.”

It was with movies en his mind that he took jobs caddying for Clark Gable, John Hodiak, Fred Astaire and others at the Bel Air Country Club. While going around, he asked them every question in the book. How did they do it? What would they advise “somebody” to do? He took care of their horses at the club. He even solicited magazine subscriptions among the film colony, hoping to meet someone who would help him. And, while working as an airplane salesman at Clover Field, he was always polishing stars’ planes for them and getting in a few hundred words. How did they get started? If “somebody” else wanted to—just say “somebody” else did—what would they advise? One day when he had polished Brian Donlevy’s plane until it fairly shone, the star wanted to tip him, but Bob wouldn’t accept it. Finally Donlevy handed him some money anyway, saying, “Here, take this and buy ‘somebody’ a book on dramatics.”

“Somebody” is going places. “How lucky can anybody be?” he keeps saying over and over. “Having directors like Walter Lang, Henry Koster. And John Ford—he’s a legend; I’d heard of him all my life. And imagine me. And it’s so wonderful to have a big studio like Twentieth Century-Fox behind you, making things happen at the right time. Photoplay has done a lot for me, too, and believe me, I appreciate it. It takes so much. It takes the whole works. So many people being nice to you, working with you, caring what happens to you. You can’t get there unless they’re all behind you.”

But the main reason he will get there is Bob Wagner the actor, whose “past” can be forgotten—the fellow who doesn’t realize that he’s an actor with a present and with a future.

THE END

—BY JANE CORWIN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1952

vorbelutrioperbir

17 Temmuz 2023Hiya, I am really glad I’ve found this info. Nowadays bloggers publish only about gossips and internet and this is actually irritating. A good web site with interesting content, this is what I need. Thank you for keeping this web site, I’ll be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Can’t find it.