Orphan In Ermine—Marilyn Monroe

The school bell rang, shattering the silence of the “quiet period” in the sunlit kindergarten on one of lower Hollywood’s more shabby streets.

Sun-tanned, robust boys and girls, arms outspread like airplane wings, flew out the door with shrill shouts of “Hi, Mom,” “There’s my daddy,” and were quickly engulfed in waiting arms. One bone thin, sallow girl with fine, blonde baby hair blowing into her eyes, shuffled out.

Why run?

AUDIO BOOK

She knew nobody would be waiting for her. There was no expression on her sullen, withdrawn face as she stood silhouetted in the doorway, watching the glad reunions. When everyone had departed, the little girl brushed the hair from her eyes, smoothed the badly-ironed, too-large dress, took a better grip on her tin lunchbox and slowly sauntered up the street to what, at the moment, she called home.

That little girl was the girl you now know as Marilyn Monroe.

Seated in the Twentieth commissary one day recently, shortly after she’d returned from making “River of No Return,” she recalled the story. Her eyes turned somber and she said, simply, “I remember that as though it happened yesterday. All the kids but me running up to their fathers or mothers. You know,” she paused, a tiny frown creasing her forehead, “I never even knew my father. Someone told me he died before I was born, but later I learned that he’d just disappeared. Nobody knows where.

“I’ll never forget my first day at school. I’d been living with an English family at the time. They lived in a crowded little flat in an auto court near the Hollywood Bowl. When they were lucky, they worked at the studios as extras and bit players. The first day of school they said they were sorry, but I’d have to go by myself because they were working. I’d been scared all of my six years, but that day I hit a new low. The other kids had a mother or a father with a nice comforting hand to hold on to while they registered. I was alone . . . When the teacher asked me why my mother didn’t come with me, I just hid my face and bawled.”

As Marilyn talked in her shy, tense, little-girl voice, slowly groping for just the right words, it was easy to understand what it was that a sensitive man with whom she’d once worked meant when he said, ‘‘She gives you a lump in your throat and a gleam in your eye at the same time.”

Earnestly, Marilyn continued, “I was never happy in grade school—I went to lots of them in different neighborhoods. I always felt in the way; I stuttered and the others made fun of me; they all had their own little groups and I didn’t know how to go about pushing my way in. They called me ‘Norma Jean—the human bean.’ ”

Her eyes clouded as she voiced those painful reminiscences. And then they brightened warmly. She smiled as she went on. “But you know, nearly all those years seem a blank to me now. Not long ago I read a psychology book that said it’s possible to forget unhappy periods, whole years of your life. It’s as if they’re mercifully wiped out—pushed back into your subconscious. I know that’s true.

“But when I was twelve, something happened to make me want to quit forgetting. Up till then, I thought I was the ugliest girl in the school, and then suddenly my figure filled out like a woman’s and the boys began to notice me. At fourteen, I was elected ‘Oomph Girl’ of Emerson Junior High School and it was the biggest thing that ever happened to me. But the girls were still unfriendly.”

At that moment, one of those strange coincidences happened—as if to underscore her words. A successful young Broadway actress shepherded by a press agent, took the table next to ours. As the press agent leaned over to make the introductions, the actress stared at Marilyn with the naked revulsion usually reserved for objects that crawl out of the woodwork. The very air appeared to congeal with the iciness of her one-word greeting. In Hollywood, “hellos” come in three categories—big—medium—small. What Marilyn got was infinitesimal. Her delicate face was drained of expression, and for a fleeting moment one could see again that pathetic little figure leaving the school—alone.

Marilyn said nothing for a few stunned seconds. It was as if she were thinking, “Who am I that a famous Broadway actress should be nice to me?” Marilyn had said nothing, either, when she was on loan-out to another studio and made a film with an important star who ignored her, scarcely uttering a social word during the entire making of the picture. Marilyn is honestly frightened of female stars—awed by them. Though she wants desperately to have them like her, she doesn’t know how to bring it off. And that’s why she probably has fewer friends than any Hollywood glamour girl.

It’s hard to believe the truth about Marilyn. Stripped of her publicity coating of sexy innuendo, Marilyn Monroe is shy and naive—a tense, confused childlike figure desperately in need of finding acceptance, love and security. Given even a modest amount of genuine interest, she expands like a wild flower after a spring shower.

The result is that there are two Marilyn Monroes—a daringly dressed worldly- looking woman; an unsophisticated girl who can cry her eyes out in private because someone has slighted her. Marilyn’s early obsession with her lack of beauty and brains made her feel that there was nothing about her to inspire interest. She has, therefore, gone to extremes to make herself appear worthy of recognition and affection. Through some miracle, she has escaped becoming hardened and cynical, but she has been unable to escape a deep- rooted feeling of inferiority.

If the actresses who snub her so viciously were to meet Marilyn on a woman-to-woman basis, they would discover there’s much more to The Monroe than meets the eye. They’d find her very direct, almost embarrassingly earnest. They’d learn she has only one serious affectation—the deep, breathless, little-girl voice which one astute observer says “causes her to speak English as if it were a foreign language.” And they’d find, too, that she’s the loneliest gal in town; that, in connection with her, the description “dumb blonde” is unwarranted; that she is completely unlike the character she portrays in films; that she discards the sexy accoutrements of her professional life when she is being herself.

So far, three understanding and deeply perceptive women—Lucille Ryman, former talent scout at M-G-M, who took the penniless girl into her home and gave her spending money; Natasha Lytess, dramatic coach, who had faith in Marilyn’s potential as an actress when no one else did; and Jane Russell, one of Hollywood’s friendliest stars, who calls her “Baby Doll”—have been drawn to and befriended the girl with no talent for making close women friends, no ability to project her warmth.

Despite the fact that she has become an American institution as well-known and highly regarded as hot dogs or baseball, Marilyn herself is not convinced she’s important. “Her self-confidence is practically nil,” observed one of her co-workers. “She’s as scared as an animal in a cage, and you see this most of all when she has to make a public appearance. That girl suffers torments; she turns pale and panic- stricken and will ask you thirty-eleven times if her hair looks all right; if her dress is okay; if her make-up is on straight. You have to practically push her up the aisle, but once she’s on the stage, she gives a terrific performance—on pure nerves.”

So unsure of her ability is Marilyn that she spends the major part of her spare time taking one lesson after another—coaching from Natasha Lytess; dancing and singing lessons from the studio’s experts, Jack Cole and Ken Darby; body-pantomime from one of the country’s finest dance-mimes, Lotte Goslar; drama from the famous Michael Chekhov (whose book on acting is Marilyn’s guide). Back in her earliest modeling days (when a dollar bought a day’s meals), Marilyn spent every cent she could afford on lessons because she was positive that she had no natural talent, that she had to be guided every inch of the way.

Even today, before she steps onto the sound stage for a scene, she rehearses her lines and action again and again with her coach. And after the scene is filmed, she dashes to Miss Lytess, in the manner of a dependent child running to its mother and asks, “Was I all right? Did I do it the way you wanted me to?” Some of Marilyn’s directors, who like to do their own directing, are unhappy about this blow-by-blow dependence on another and it has, understandably, led to some strained situations. One veteran European director, who frequently blows his top, once screamed out at the coach: “You were the worst actress in Russia. Are you trying to make this girl the worst actress in Hollywood?”

One day Natasha was ill, complained of flu symptoms and told co-workers that she would not be in the next day. But next day, there she was. When someone asked her why she wasn’t home in bed where she belonged, she said, “Marilyn called me late last night to say she couldn’t possibly manage without me today.”

This might seem to be the brashest kind of selfishness; but that’s far from the case. Marilyn acts much as a child does—with no conscious thought of others. For Marilyn hasn’t yet grown to emotional maturity—she is still unable to stand on her own two feet. Some of the people who work with her are aware of this; they know that Marilyn lives in a world of her own and is essentially a gentle, kind person who would not knowingly harm anyone. And so they condone her habitual tardiness, her unheeding actions.

Others are not so sensitive or understanding. A certain photographer, for instance, growling at her habit of showing up hours late, once said, “Some day Marilyn is going to need me and I’ll give her the same treatment. Right now I’m under orders to photograph her and I have to put up with her rudeness.” What he doesn’t realize is that Marilyn is, consciously, no ruder than a baby would be. So preoccupied is she with herself that she is completely oblivious to the irritation she causes in others.

And what some of her directors haven’t realized is that Marilyn is still seeking the all-encompassing love and acceptance which the normally brought-up youngster receives as a matter of course from his father and mother. Explains Marilyn in her soft, almost pleading voice, “From some directors who really understand me, I’ve received the most wonderful help. From some, I haven’t. I can only be as good an actress as the director makes me. When I get on the sound stage I feel lost and helpless. If a director takes an interest in me, takes me aside and offers assurances on how I’m doing, then I feel better.”

Naturally, directors are busy, harassed people and a few can’t understand why Marilyn feels slighted because they don’t devote all their attention to her. Nor do they understand that Marilyn, because of the early numbing period of her life, is working desperately hard at two things when she is before the cameras—trying to do a good job and trying to make everyone around her like her.

“When Marilyn Monroe,” explained one director, “stops acting like a person who mounts a horse and rides off in every direction, she’ll become a really fine actress. She’s got the stuff; what she needs is a hard core of inner self-confidence which will let her draw upon her own resources, thus releasing her from slavish devotion to those she relies on,”

Right now, those who know Marilyn best believe that she should concentrate more on her health. She’s really an overworked, completely exhausted girl. She should never have been allowed to rush from film to film with no time off. Marilyn’s anemic; her eyes are a little leaden from seven days a week of acting, dancing, singing, rehearsing. She suffers from severe colds which frequently send her to the hospital. Her migraine headaches, skin rashes, low blood pressure stem from mental upsets more than from physical causes. A long vacation would aid her in regaining the dazzling vitality which is the secret of her fantastic sex appeal.

Nor would experts say Marilyn is really ready to cope with the mature give-and-take of marriage. From the husband she married in her teens (she rather pathetically called him “Daddy”) Marilyn didn’t receive the strength and steadying hand she needed. But from the second man in her life, the late Johnny Hyde, a gentle, brilliant man with thinning hair and small, humorous face, thirty years her senior, she received so much help and love and human sympathy that today Marilyn can scarcely talk of him, though nearly three years have passed since his sudden death.

When she first met Johnny Hyde, Marilyn had bleached her brown hair to a reddish gold and wore it long and fluffed out around her face. Her mouth and eyes were overpainted, her skirts very tight, her blouse very low-cut, her shoes very high-heeled and ankle-strapped. Johnny Hyde taught her how to dress. “He was so good to me,” Marilyn explains slowly. “And he made me feel as though I weren’t just another stupid, stage-struck blonde. He found me when I needed him most.

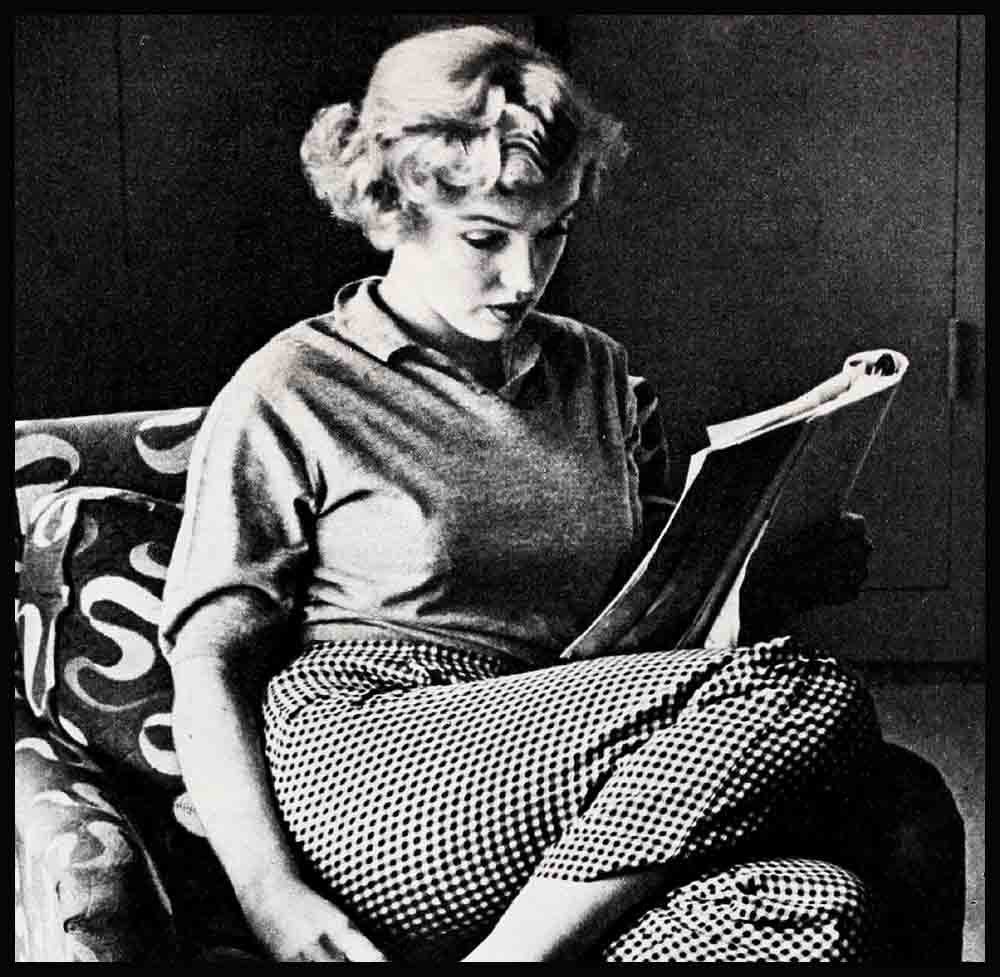

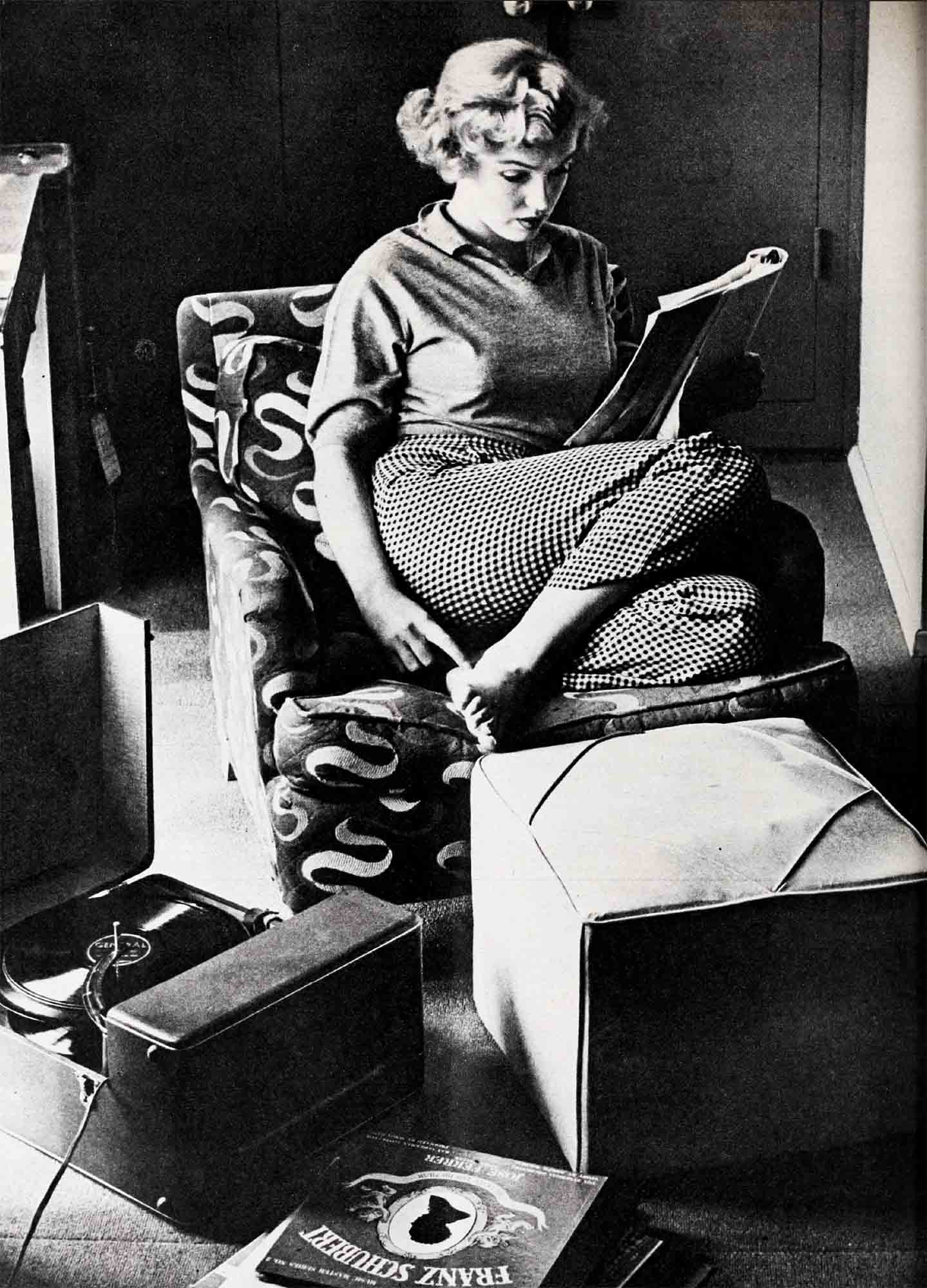

“I was living at the Studio Club and met him casually at a party. The next morning I was surprised when he called and asked me to lunch. He was an important actor’s agent with the William Morris Agency and represented such important stars as Lana Turner, Rita Hayworth and Esther Williams. He was willing to act as my agent even though the only coat I had was a beat-up polo coat, and I went to interviews without stockings before it was fashionable, because I couldn’t afford any. “I know you’ll be a big star,’ he used to tell me when I was struggling just to eat and pay my rent. He inspired me to read good books, to enjoy good music, and he started me talking again. I’d figured early in life that if I didn’t talk I couldn’t be blamed for anything. I loved Johnny very much—kind of different, maybe, but a lot.”

A girl with a constant heart, Marilyn never looked at another man during the two years she was Johnny Hyde’s constant companion. He loved her deeply, while she focussed her entire being on her budding career. And she refused his repeated offers of marriage until it was too late and she stood miserably weeping outside his hospital room.

The third important man in Marilyn’s life—as everyone is aware—is tall, dark, lean-faced Joe DiMaggio. Whether or not Marilyn and Joe will marry is a question that no one would risk answering at this time. But here is what a thoughtful observer who knows them both has to say: “Personally, I don’t believe they have enough in common to make a good marriage. Marilyn cares nothing about baseball or out-door sports, certainly wouldn’t give up her hard-won career to live in New York or San Francisco where Joe’s business interests are.

“Joe, who’s basically simple, forthright, neither witty nor worldly, is completely without interest in Marilyn’s ventures into ‘book larnin’,’ her tremendous classical record collection, her deep discussions of the Stanislavsky method of acting.”

In short, this “Orphan in Ermine” is still searching for the father she never had—the emotionally stable giant into whose hand, like a happily trusting child, she can place her own.

Only when she finds him (and she may yet feel she’s found this man in Joe) will she be free of the childhood fears that have dominated her entire life.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1954

AUDIO BOOK