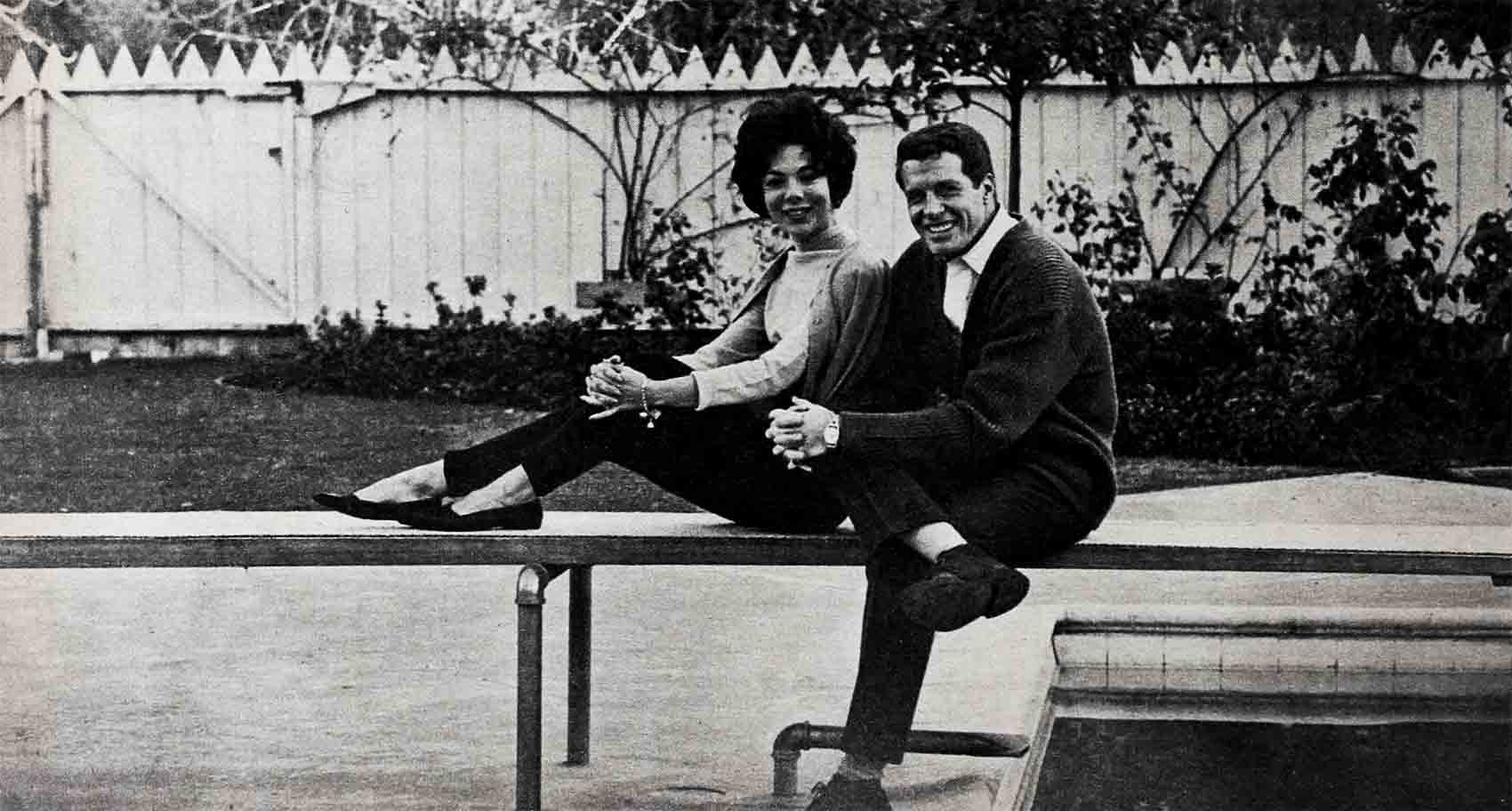

Three Little Words . . . Behind Them, What A Story?—Robert Horton & Marilynn Bradley

Bob Horton said it. “I love you.” He could still hear how it sounded the first time. His voice cracked right in the middle of the three words. But after that it was easier, and he said it often. He and Marilynn were engaged . . . they were married . . . and three months later the honeymoon was still on. It looked like forever.

That’s the ending to this story. But it’s the beginning of the story that Bob Horton still can’t believe. . . .

He was just like any other bachelor.

To his friends, he’d say, “If I could only find a nice girl, I’d marry her.”

To himself, he’d say, “Married—that’s the last thing I want to be.” Like any other bachelor, he wasn’t going to give up his freedom without a fight. He was more stubborn than most. He’d tried marriage twice, and twice it hadn’t worked.

But if his friends wanted to introduce him to nice girls, he’d meet them. And he’d go out of his way—in fact, way out—to say hello to a nice girl.

But every time he found one, he’d also find something wrong with her.

When he met Marilynn Bradley, it was the same way. She was standing in the middle of a bare stage in Warren, Ohio, and even under the glare of the naked rehearsal light, she looked pretty. He could tell she was nervous from the stiff way she stood and the way her hand was clenched at her side.

“My leading lady in ‘Guys and Dolls,’ ” he thought, but from the minute they were introduced, he could feel an attraction, a strong one.

But, as with all the other girls he’d met. Bob held back.

He knew the one thing he didn’t want was another mistake. He’d made two painful ones already.

He’d been just twenty-one, still at UCLA, when he married Mary Katherine Jobe. For almost six years, it was a good marriage. Bob finished school and, burning with ambition, began to get his career underway. The night he came home with an invitation to a big Hollywood party, he acted like someone who’d finally grabbed the brass ring on a merry-goI round.

I “Get yourself a new dress,” he said, waving the invitation triumphantly at Mary. “We’re going to meet the biggest people in town.”

At the party, at the very moment he’d be shaking hands for the first time with people he’d admired all his life—knowing that they really liked and accepted him—he would glance toward the corner of the room and see Mary, shy and retiring, and suddenly the whole evening fell flat. It was the first of many such evenings.

When other people weren’t around, Bob and Mary were happy. But out in the world where Bob felt he had to find his way, their marriage fell apart. One day Mary even quit her job as a script reader for Columbia to become a waitress in a Hollywood ice cream parlor. “Why?” Bob asked her. “Why?” She told him on the new job she wouldn’t have any responsibility. He tried to stop her from crawling into a shell. She had good looks and a good mind, he reassured her, and shouldn’t waste her talents. She didn’t see it that way. Suddenly each had needs the other couldn’t fill—or even understand. They ended the marriage.

When Bob married again, he felt that he had learned enough from his first marriage to make it work the second time. He and Barbara Ruick were playing gay, romantic roles together at M-G-M, and one day in 1953—just like a scene out of one of their movies—they eloped. Everyone thought it was a perfect romance and, for a while, it was.

The first sign of trouble came when Bob’s career cooled and Barbara’s got hot. Out of a job, Bob stayed home and kept house while Barbara earned the money for the groceries.

“I think you’re beginning to take me for granted as a housekeeper,” Bob said one day, only half joking.

Barbara looked up from the dress she was ironing. “Well,” she answered, “it’s too bad you don’t know how to iron, too.”

She was late for work and she’d spoken too quickly, without thinking. But the damage was done.

“From Barbara’s standpoint,” Bob said later, “I did let her down. There I was, turned into a housekeeper instead of the secure, promising actor she’d married. A husband and wife should be proud of each other—dressed up or messed up—and if they can’t be proud, there’s something very wrong between them.”

They were divorced in 1956.

What was wrong?

Bob couldn’t be blamed if, after that, he was a cagey bachelor. You never know a girl till you marry her. He knew that was true now and he also knew that by the time you married her, it was too late. He had been burned twice. What was wrong? Both girls he’d married had been nice girls. Wonderful girls. Maybe it was marriage itself that was wrong.

Maybe there was safety in numbers. Lots of girls could singe you, but only one girl—only love—could burn you. So he dated sweet girls, exciting girls, tall girls and short girls. But always there was something wrong. Usually the trouble was—the girl wanted to marry him.

It happened often. Variations on the same trick. His phone would ring and he’d hear a soft voice (Sue or Anne or Ruth or Priscilla) ask, “Bob, did I leave my compact in your car?” When he went to look, the compact was always there. He was positive she’d left it there on purpose, trying to get him to ask her out again. But Bob wouldn’t bite. If a girl forgot her compact or her comb or her gloves, he’d send them back by mail. And that was that!

But with Marilynn, it was different. There was something about her that first day on ine Dare stage in Warren, Uhio—she looked so pretty, she seemed so helpless—that made him want to go over and put his arms around her. But the part of him that was always suspicious of girls, that made him alert for their wiles and tricks, said, “Stay away from her. It’s all an act. She’s trying to make me feel sympathetic.”

If it was an act on Marilynn’s part, it was a good act. Throughout the run of the show in Ohio, she seemed to be under a terrible strain—and helpless to do anything about it. But Bob kept his distance. Then it was goodbye. They met again briefly in Detroit to do the show again a few weeks later, and then goodbye once more.

But the next time they met, some time later, Bob found out the truth about Marilynn, what was really the matter with her. It hadn’t been an act. The trouble with Marilynn Bradley was that she was married!

During those weeks in Ohio and Detroit, she was keeping her problems to herself, trying desperately to save her marriage. But now she and her husband had separated completely, and were going to get a divorce. She was still very pretty, but that tense, helpless look had gone.

Shortly after that. Bob finished a smash Christmas engagement at the London Palladium and was looking forward to a fabulous weekend in Paris to celebrate. But at the last minute he hopped onto a plane going in another direction—to New York—where he spent New Year’s Eve with Marilynn. It was lovely, but not love. Not yet.

When Marilynn arrived in California and they began to date, he was puzzled. He’d take her to a football game or dancing or on a long moonlight drive along the coast. Afterward, he’d think, “Here we go again.” He’d search the car.

But Marilynn didn’t follow the pattern he expected. She never lost her compact.

If he didn’t call her, she didn’t call him.

If he invited her over for a barbecue, she could be there all day without suggesting that the couch in the living room would look better against the other wall.

If they were sitting around quietly watching TV, she never once said, “Just like married folks.” He was the one who said it. Or thought it.

She left the pursuing up to him—and so he pursued.

Bob began to feel the joys of bachelor life were really not so joyous after all. He counted up his freedoms and found there were lots he could do without: the freedom to dress up and drag a date to a noisy bash when you were tired and would rather watch TV . . . the freedom to be lonely at the very moment you needed someone with whom to share a joy or sorrow . . . the freedom to skim just the surface of life. He had to admit being a bachelor wasn’t so great. Neither is marriage, he’d quickly remind himself. He wasn’t giving up without a struggle.

Just in time

And then, just in time, he found something wrong with Marilynn.

She learned to drive a car. He had to admit, she got pretty good at it. In fact, even when she wasn’t behind the wheel, she was driving.

Bob was at the wheel, driving across town with Marilynn to the Cocoanut Grove in the Ambassador Hotel.

“Look out for that car,” she told him.

He looked out.

“There’s a stop sign. . . .”

He stopped.

“You have the green light now. . . .”

He went ahead. But he wasn’t happy.

By some minor miracle, they found a parking spot right in front of the Ambassador. Bob pulled up near it, put the car in neutral and turned to Marilynn. “Okay,” he said grumpily, “you drove the car all the way down here. Now you park it!” He got out of the car, slammed the door and, without a backward look, walked into the hotel.

It was the first time Marilynn had ever grappled with the problems of parallel parking. For half an hour, she edged the car back and forth, in and out. The car in front seemed to be creeping toward her, the space seemed to get smaller. The curb kept moving in and out, bumping against the wheels. She was getting flustered and a little panicky. But she was stubborn.

Bob, waiting for her in the hotel lobby, began to feel sorry about the way he’d acted. After thirty minutes, he began to get worried about Marilynn, too. He walked back out of the hotel to look for her.

He found her behind the wheel, looking pleased. The car was parked. “You did it!” he shouted. A man, passing by, turned to stare at him, but he didn’t care. He was so proud of Marilynn, he forgot all about being angry. She didn’t remind him.

She gave up back-seat driving on the road. Instead, she took it up in the sky. Bob was piloting his own plane, following Route 66. when he lost the guiding ribbon of the road. Marilynn unfolded a huge map and offered to help. This time. Bob knew he couldn’t ask her to park when they finally arrived. “If you’re going to drive the plane from the hack seat, too,” he said instead, “you better learn how to drive it from the front.”

She agreed. She went to ground school and learned navigation.

She was quite a girl. Bob had to admit it. Even when, finally, he managed to find something wrong with her, like her backseat driving, it turned out it didn’t really matter. They could both laugh about it. He could feel himself weakening. Marriage didn’t work before, though, he reminded himself, why should it work now?

Marilynn had the answer, of course, hut she wasn’t telling.

Three little words

Not long after, Bob decided to move out of his small cottage. He looked around and found a bigger house he thought he might like in the old rolling hills that rim the San Fernando Valley.

He drove out one day to show it to Marilynn and to his business advisor.

His advisor looked it over. “It’s a good house for you,” he said. They walked in and he sized up the possibilities of the spacious living room. “You can entertain the top people in the industry here,” he said. “They’ll he impressed.”

Then Marilynn came in. She’d stopped to pick an armful of roses from the bushes that edged the entrance to the garden.

She looked around. The afternoon sunlight slanted through the windows. “It’s a good house for you.” she said thoughtfully, “you’ll he comfortable here.”

She pointed to a raised platform at the end of the room. “It’s just right for a piano.” she said, “. . . . for when your old friends come over. You know how they like to sing around a piano.”

Bob smiled at her. gratefully. It was so like her. Nothing about impressing people, about using the house to help His career. She’d looked at it and thought about his comfort, about whether it would be right for his kind of life, for his friends.

They wandered through the other rooms. To Bob, it suddenly seemed like a big house for just one person.

“You’ll be comfortable here,” she said.

He nodded. To himself, he thought, “I’ll he lonely here.”

For the first time, he wished she’d said we. He tried it out in his mind. “We’ll be comfortable here.” That sounded better.

But when they’d dropped off his business advisor and he and Marilynn were alone, that’s not what he said.

Instead, he said just three little words.

THE END

—BY VI SWISHER

Be sure to see Bob in “Wagon Train” on NBC-TV, Wednesdays at 7:30 P.M. EST.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1961

zoritoler imol

3 Ağustos 2023I don’t even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was great. I don’t know who you are but certainly you are going to a famous blogger if you are not already 😉 Cheers!