Elizabeth II Ascended The Throne

A Good Omen

The bells tolled, the black-draped drums acknowledged and echoed the news. King George VI was dead, and a 25-year-old young woman ascended the throne of a realm that encompasses a quarter of the globe and a fourth of its inhabitants.

The news shocked, saddened, and in a strange fashion, inspired. A steadfast and modest King had died peacefully: this fact eased the sadness. The new Queen, young and popular, bore a proud name and the promise of a new era. In an age which prides itself on practicality, dismisses pomp as pretension, and regards royalty as an empty anachronism, the meaning of the Crown seemed suddenly clearer. Respect, earned and freely given, is its strength. Tyrants might demand but could not command loyalty so spontaneously offered. At a precarious moment in Britain’s history, the passing of George VI and the accession of Elizabeth II strengthened the one tie that still binds the Commonwealth to the mother island—fealty to the Crown.

In Britain, political activity was stilled and party strife suspended at a moment when Parliament was plunging headlong toward a serious split over foreign policy, its first since 1940. The news postponed a critical struggle for power within the Labor Party, and rescued Winston Churchill from a situation that was causing him real concern. The issue which the House of Commons debated was whether Britain should stand beside the U.S. in whatever new perils may come in Asia. Tangled in that issue was a latent mistrust of the U.S., a concern over Britain’s role of junior partner, and the political ambitions of Left-Wing Rebel Nye Bevan.

The debate became acrimonious and mischievous. To hear the Bevanites tell it, it was the U.S., not Communist China, that menaced the peace. In the heat of the Laborite assault on Churchill’s foreign policy, Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden was jolted out of his usual debonair mastery of the House, even lost his temper and apologized for it. Churchill maneuvered desperately to head off an end to the bipartisanship in foreign affairs which has lasted through World War II and six years of Labor government. Abruptly, the news from Sandringham House snuffed out the whole debate. One Laborite muttered: “It’s a wonderful get-out for the old scoundrel [Churchill].” The debate will be resumed, but the moment and the mood will be different.

In London’s winding, grey streets and Britain’s wintry countryside, cares, queues and cold war persisted. But for the moment, they were overshadowed by the ceremony of death and the proclamation of a new reign.

Drawn by six black horses, a caisson bearing the King’s coffin made its way from Sandringham to the railroad station, down a two-and-a-half-mile winding road lined by hushed thousands. Prince Philip and the Duke of Gloucester walked behind the caisson, followed by a limousine in which rode the women in the family, veiled in black. A special train took the royal party to London, 103 miles away. There, on a windy, rainy afternoon, the coffin was led through crowded, silent streets to Westminster Hall, where the King would lie in state until his funeral this week.

Now began the second Elizabethan Age, and in its name the people of Britain saw a good omen.

With consent of heart and tongue.

(See Cover)

On her 2 ist birthday—it was only five years ago—a British Princess faced a microphone in South Africa and in a clear girlish voice made a solemn promise to her father’s subjects all over the world. “I declare before you all,” she said, “that my whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service and the service of our great imperial family to which we all belong.”

Millions of British subjects, who felt a quickening reassurance at the sound of these words so simply spoken by the girl who would one day become their Queen, felt a further reassurance in the thought that she was still a girl, and that her promise would not, for many years, be brought to the test. Last week, with fearful suddenness, Britain’s Princess entered the life of service she had promised.

With her husband Philip, Princess Elizabeth was once again visiting her father’s African realm when the tragic news reached her.

Queen Unaware. “The King is dead; long live the Queen,” stated thus traditionally with hardly a pause, is no mere paradox. It encompasses a principle close to the essence of British monarchy; that the realm is never, even for an instant, without a ruler. Britain’s new Queen, the sixth woman to rule over England, became sovereign without even knowing it. With Philip, her staff and their game-hunting hosts, she was spending the night in a tree hut in Kenya’s Royal Aberdare Game Reserve, watching big game gather at a jungle waterhole. It was one of the rare moments of her projected five-month tour during which Elizabeth could really enjoy herself. As a herd of 30 elephants lumbered into view before sunset, she seized her husband’s arm. “Look, Philip, they’re pink,” she whispered. The elephants, grey by birth, had been rolling in the pinkish dust of the forest. Prince and Princess delightedly snapped pictures.

Too excited to sleep during the rest of the night, Elizabeth kept leaving her cot to watch other nocturnal visitors at the waterhole. In the morning she breakfasted on bacon & eggs, and tossed bananas to baboons below. Just before noon, clad in apricot-colored blouse and brown slacks, Britain’s Queen, unaware of her high position, left the hut in high spirits over her “tremendous experience” and vowed to come again soon with her father. “He’d love it,” she said.

Back at their cedarlog lodge (a wedding present from the people of Kenya), Elizabeth and Philip bathed, rested, changed their clothes and settled down to discuss plans for pruning out some gum trees which hid their view of snowcapped Mount Kenya.

It was not until early in the afternoon that Philip got the news (by telephone from a local newspaper) that changed their lives. He sent an equerry to call London for confirmation, then gently led his wife down to the river’s edge and told her that her father was dead. The Queen returned to the lodge on her husband’s arm, shaken but in full command of herself. All that afternoon, she kept busy supervising the myriad arrangements for the long trip home, penning formal regrets to the hosts she would have to disappoint, bidding goodbye and signing photographs for the staffers and attendants she was leaving behind.

At 3:30 P.M., Elizabeth took a last walk around the grounds with Philip, then climbed into a car for the drive to Nanyuki Airport. A Dakota flew the royal couple to Uganda, where the same fourengined Argonaut that brought them from London was waiting to carry them home again. A few minutes after the first takeoff, the plane’s pilot picked up a radio message of condolence from Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Then, at last, Britain’s Queen broke down in sobs.

Reassuring Farewell. The great city which would be her Capital awaited the new Queen’s arrival in stunned silence. “I’ve never seen Piccadilly Circus so quiet,” said a London doorman. Only four months ago, King George’s people had worried through his terrible operation and his slow recovery. Then they had seen him, a week ago, in newsreels and news-photos, bareheaded and seemingly hale, waving a cheery farewell to his daughter at London airport. Despite his still haggard features, they had felt a surge of relief at the apparent improvement in his health. The royal tour itself was reassuring: the Princess would never have undertaken so long a trip if her father were not well on the road to recovery. But Elizabeth could know the truth no more than they.

Lowered Flags. As the news of the King’s death spread in ever-widening circles out of London, many met it in bewilderment or plain disbelief. “ ’Ere now, don’t you go spreading rumors about like that,” said a burly policeman at Sandringham’s gate to an early-bird reporter. Even after the rumor became an official bulletin, announced by the BBC and newspaper extras, some at first refused to believe it. “After all,” argued an indignant Londoner, “Mr. Churchill didn’t announce it.” “It can’t be true,” cried an old lady at the black banner headlines on a London news stall. “It can’t be true.”

With sorrow and the tolling of bells.

But true it was, and gradually the realization settled on Britain’s Capital. Silence, broken only by the subdued march of traffic and the dismal tolling of church bells, took over. Union Jacks fluttered to half-staff. Shops and factories all over the nation closed down. The BBC canceled all remaining programs after its initial bulletin. Cinemas and theaters called off their shows. The stock market closed for the day. At Lloyd’s, the famed Lutine Bell, historic herald of momentous news, clanged once, and all business ceased. Even London’s famous burlesque house, Windmill Theatre, which boasts of never having closed even during the Battle of Britain, shut its doors.

Many Londoners instinctively headed for Buckingham Palace, to stand for hours in a cold drizzle of rain, despite the fact that none of the royal family was in residence there. Others gathered outside Downing Street, the Prime Minister’s house, outside Clarence House, Elizabeth and Philip’s home, outside Queen Mary’s Marlborough House and dark, rambling St. James’s Palace, where the new Queen’s accession would be proclaimed. They were not waiting for a show; no pageantry or display was expected that night. They just felt that was the place to be.

Great & Humble. In King George’s island kingdom and in the far reaches of his still vast dominions, there was a feeling of individual loss in the passing of this simple, decent man whose spare, frail person had embodied such personal endurance, such symbolic might. Far beyond the limits of his Commonwealth, in lands that offer Britain no more than grudging respect, great men and humble men paused to acknowledge the death of the British King.

In Rome, the Soviet Standard atop the Russian embassy on Janiculum Hill beat all other official flags, including even the British, to half-staff. In Cairo, where charred and blackened ruins stand in silent testimony to Egypt’s hatred of all things British, King Farouk declared a 14-day period of public mourning for the dead sovereign. In India, whose republican government no longer recognizes the Crown, bazaars were closed and a national eleven-day period of mourning was proclaimed. In Dublin, a little Irish lady stood crying on a Street comer as she read of the British King’s death, while the Republic’s President Scan O’Kelly made plans to attend the funeral of the man whose crown was a symbol of his nation’s traditional oppression.

From Paris, Stockholm, Oslo, Rio, Copenhagen, Washington, New York, The Hague and other great cities of the world, official messages of sympathy poured in to the bereaved royal family. Salutes of 56 guns (one for each year of the dead King’s life) boomed from Tower Hill, and from the gun turrets of British warships on most of the seven seas. In Melbourne, Australia, a group of bellringers in St. Paul’s Cathedral heard the news just as they were practicing a merry peal of welcome to Elizabeth and Philip; the bellringers set their bells tolling mournfully instead.

“The Queen’s Keys.” But even as the shocking news interrupted the smooth flow of past into future, a new present was making itself felt. The King was dead, but the Crown remained. and it must be fitted promptly to a new head. In London’s High Court, King’s Counselor Harold Shepherd had just finished cross-examining a defendant when the news came. The court adjourned. Ten minutes later, the lawyer resumed the floor as Queen’s Counselor. Painters at another London court set to work painting out the sign “King’s Bench” and replacing it with “Queens Bench.” “Who goes there?” sang out the sentries in a traditional nightly ritual at the Tower of London. “The Queen’s Keys,” came the new answer. There were a multitude of adjustments to be made in a nation where everything is run in the name of the sovereign. Six months hence, for instance, a new coinage would appear bearing a likeness of the Queen, facing, in accordance with tradition, in the opposite direction from her predecessor. But first, there was the complicated procedure of establishing without question the sovereign’s identity and right to sit on the throne.

King George’s death caught Parliament in the midst of one of the fiercest debates in its recent history, and instantly stilled that debate. On Wednesday afternoon, the House of Commons met briefly to hear the news officially announced by the Prime Minister, and then recessed. The government ministers, together with leaders of the Opposition, the Privy Council and other prominent Britons, had a more important meeting to attend: the meeting of the Accession Council, the oldest governmental convocation in England, 192 of whose members gathered at St. James’s Palace to determine formally the new sovereign’s accession and title. The council’s task was complicated by the fact that Elizabeth, the first British monarch since George I to be out of the country when her predecessor died, was still 4,000 air miles from London and hence unavailable to proclaim, as required, that she is a Protestant. Nevertheless, in two hours, the councilors decided that she was indeed the rightful sovereign, and at 7 P.M. the House of Commons met again to hear their report and swear allegiance to the new Queen. Then they adjourned. That night London was dark and still. The neon lights in Trafalgar Square and Piccadilly Circus had been turned out and, except for restaurants, all public places were closed tight.

Next day the Queen herself arrived at London’s airport. Winston Churchill had urged Londoners to stay away, and a mere handful of reporters and officials were there to greet her. A black coat hiding her greyish-blue dress (she had taken a black dress with her, but there had been no time to unpack it), her face a pale, wan oval beneath a tight black hat, Elizabeth stood in the door of the plane, looking down at the bared heads of the men who had come to meet her. With a brave half smile, she came quickly down the steps. The black-clad semicircle bowed as one man. Elizabeth shook hands with the Prime Minister. Then, followed by Philip, she walked gravely along the line of Privy Councilors, shaking hands and murmuring a word to each. The Argonaut’s eight crewmen disembarked and saluted, and the Queen shook hands with each of them. Then she climbed into her waiting car and rode to Clarence House, past rows of silent, bareheaded subjects lining the road, mile after mile. As she stepped from the car, a guardsman tugged on a halyard and sent the Royal Standard fluttering up the flagstaff of Elizabeth’s house.

The High & Mighty. When King George’s only sister, the Princess Royal, distracted at the news of her brother’s death, had rushed into her mother’s apartment, hair askew, 84-year-old Queen Mary had told her: “Please do your hair properly when you come before the Queen.” More than anyone, perhaps, Queen Mary was conscious of the great destiny that had come to her granddaughter, the princess whom she had so often reproved and scolded in the past. When Elizabeth entered Clarence House, Queen Mary was waiting, perfectly prepared, to curtsy before her. The Queen talked with her grandmother for half an hour, put in a call to Sandringham to her mother and sister, and went over the arrangements for the King’s funeral with the Duke of Norfolk (Earl Marshal of England)* and the Earl of Clarendon (Lord Chamberlain). That night, while all Britain listened to Churchill’s eIoquent eulogy of her father, she rested.

Next morning, followed at a discreet distance by her husband Philip, the Queen walked along the garden path linking Clarence House with St. James s Palace, to receive the homage of her Privy Council and sign the oath of accession. An hour later, in a blaze of medieval pomp, her accession was formally proclaimed. Crowds of thousands jammed Pall Mail, St. James’s Street, Friary Road and The Mall. Four State trumpeters, resplendent in gold-laced tabards, stepped out on a balcony of St. James’s Palace, followed by sergeants-at-arms bearing maces. In the courtyard below stood guardsmen holding rifles and bandsmen with drums muffled in black. As the trumpeters blurted a brassy fanfare, Britain’s Garter Principal King of Arms Sir George Bellew—flanked by the Earl Marshal, two more Kings of Arms, six Heralds and three heraldic Pursuivants, all dressed like himself in tabards and cockaded hats and bearing staffs of gold, silver and ebony—stepped forward and raised a huge parchment.

“Whereas,” he cried, “it hath pleased Almighty God to call to His Mercy our late sovereign lord, King George VI, of blessed and glorious memory, by whose decease the Crown is solely and rightfully come to the high and mighty Princess, Elizabeth Alexandra Mary, we therefore Lords Spiritual and Temporal of this realm . . . do now hereby with one voice and consent of tongue and heart publish and proclaim the high and mighty Princess Elizabeth Alexandra Mary is now . . . become Queen Elizabeth II, by the Grace of God, Queen of this realm and all her other realms and territories, head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith, to whom her lieges do acknowledge all faith and constant obedience with hearty and humble affection; beseeching God by. Whom kings and queens do reign to bless the royal Princess Elizabeth II with long and happy years to reign over us. God Save the Queen.”

At the last words, the half-staffed flags of London climbed upward once again to fly at full-staff for six hours, in honor of the new Queen. The sun itself, as though a providential stage manager had planned it, chose that moment to break through the dismal overcast. As the heraldic procession moved on, in gilded coaches, to proclaim the great tidings at other key points in the city, Londoners felt a warmth in their hearts like the sudden sunlight. The dead King was not forgotten, but today they had a new Queen.

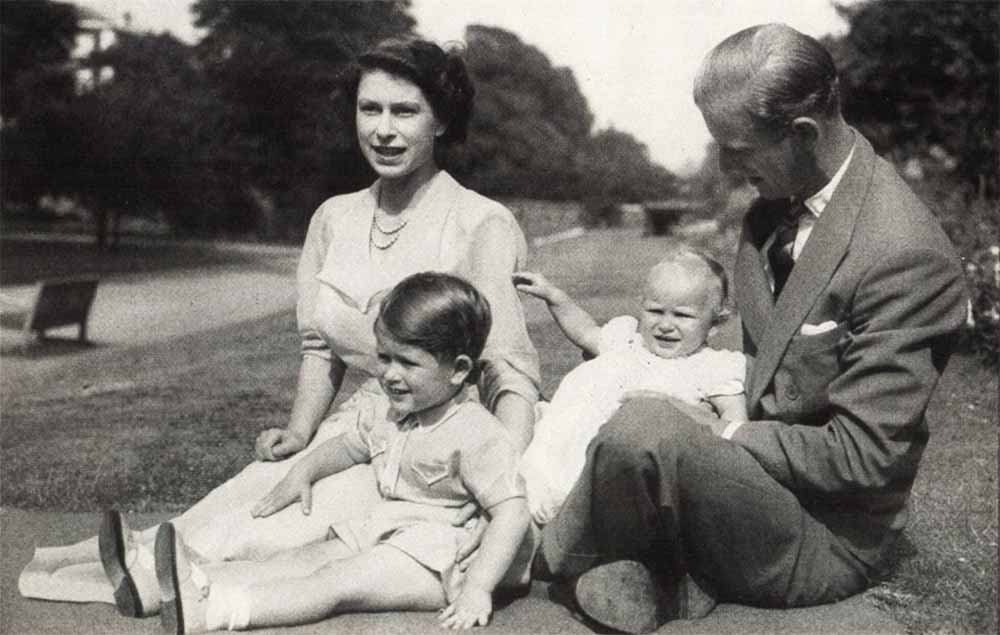

Lilibet, R. Long after Elizabeth herself had any realization that she would one day be Queen of England, Britons the world over had felt the destiny that lay before her. The curly-haired baby Lilibet had caught their heart and their imagination almost from her birth. As time and unpredictable fortune brought her closer to the throne, Elizabeth had proved herself more & more qualified to occupy it. As a rather fat little girl, as an earnest and leggy Girl Guide, as a shy, devoted daughter whose only rebellion took the form of insisting on doing war work like other girls, as a princess in love, as a radiant bride and young mother, Elizabeth grew up before a public which closely watched and freely commented on her progress. There had been a few lifted eyebrows, penciled higher by London’s Sunday tabloids—as on the occasion, a year ago, when Elizabeth left her children in London for three months to visit Philip, on naval duty in Malta. But most people saw nothing amiss in the fact that this shy and serious young woman, born to serve and schooled in duty, should have some fun as a service wife at her husband’s side. Certainly she returned from the Mediterranean looking tanned and healthier. It was Philip who persuaded her to slim down by forgoing potatoes, sweets and wine, and who encouraged her to become style-conscious, abandoning the fussy fashions of the Windsors for tailored simplicity.

Any lingering doubts of Elizabeth’s natural dignity and well-schooled manners were dispelled for good last year, when Elizabeth toured Canada and the U.S. with Philip, earning respect and affection wherever she went.

Unlike his three-year-old son Prince Charles, who on his mother’s accession automatically became Duke of Cornwall, Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Carrick, Baron of Renfrew, Lord of the Isles and Grand Steward of Scotland, the Duke of Edinburgh has no change in titular status: he is still simply the Queen’s husband. It is an awkward and difficult position. His last predecessor was Victoria’s German-speaking husband, and Britons took a long time getting used to Albert. Philip, born in Corfu and once sixth in line for the Greek throne, is a great-great-grandchild of Victoria and Albert, like his wife. A British subject, he is by instinct, schooling and tongue thoroughly English. But some still think of him as a foreigner.

It is up to Elizabeth to decide whether and when to elevate him to the rank of Prince Consort. Many expect that she will, at the time of her coronation. But even as a mere ducal husband, 30-year-old Philip is bound to play an influential part in the Queen’s affairs. In Canada, exercising his easy charm at his wife’s side, and managing to maintain a discreetly subordinate position, handsome Philip proved himself a graceful diplomat, an affable salesman of royalty.

Last week, as for six hours the Union Jack flew high over London, Britons regarded their royal couple proudly, in the sure sense that all would be right with the realm. The young Queen would be guided by her husband and her mother, and that was a good thing. But it was also a good thing that—as generally acknowledged—she has a mind of her own. She becomes Queen at the same age—25—as her famed namesake. By comparison with that of her ancestors, Elizabeth’s great inheritance has dwindled sadly, but England has known its greatest days under its queens. Last week, as British officers, for the first time in 51 years, directed their wardroom and regimental toasts “to the Queen’’ instead of “to the King,” Britons felt in their bones that Elizabeth will be good for them.

To Papa. Elizabeth the Queen, a girl of 25 who had lost her father, might have been pardoned for not altogether sharing her subjects’ mood of renewed hope. On the afternoon of the proclamation, in somber black, she and Philip climbed into the back seat of her crested Rolls-Royce, and headed for Sandringham. Crowds lining the London streets waved as she passed. Elizabeth smiled wanly back, but her features were still locked in sadness. Philip sat gravely beside her. once on the open road, the couple moved into the Rolls’s front seat and Philip took the wheel.

At Sandringham, where local carpenters had spent the night making a simple coffin of oak cut from the forests nearby, Elizabeth greeted her mother and sister quietly, kissed her children and then went to the second-floor room where her father’s body lay. At sundown,* a cortege of George’s woodsmen and gamekeepers, headed by a kilted pipe-major playing a Scottish lament, wheeled the bier to the parish church, where the King’s body lay in state for two days before being taken to London’s 12th century Westminster Hall, adjoining the House of Commons. Across the meadows and through the woods went the soft lament of the bagpipes. All that night the King’s gamekeepers, in green buckskin jackets and dark knee breeches, took their turns standing honor guard in two-hour shifts, four at a time, one at each comer of the coffin. All next day and the day after, villagers filed silently past to pay their last respects to their King and squire as he lay in the simple casket. Three wreaths lay on the coffin: one from his widow, one from his younger daughter, one from Britain’s Queen. The last, a white circle of lilies of the valley, camellias, carnations and hyacinths, was marked: “Darling Papa, from your loving and devoted daughter and son-in-law, Lilibet, Philip.”

Those words marked the final farewell to girlhood of the lonely young woman whose name in history would now forever be signed: Elizabeth, Regina.

Ladies with Scepters

“Famous have been the reigns of our queens,” said Winston Churchill last week. Britain’s two golden ages—the Elizabethan and the Victorian—bore the names of queens. Five queens have reigned before Elizabeth II.

Mary I (1553-1558) tried to restore Catholicism in England, but the fires of her persecutions only hardened Protestantism, increasing its popularity and making its triumph inevitable. She had a personal reason for being anti-Protestant: when her father, lusty Henry VIII, defied Rome and nullified his marriage to her mother, Catherine of Aragon, for a time Mary had to renounce her royal claims and style herself a bastard. She was an honest, well-intentioned woman who withered everything she loved and unintentionally fostered what she hated. To please her husband, Philip II of Spain, she enlisted England in a disastrous and unpopular war on France. After five years on the throne, she died alone, deserted by her husband, detested by her people, and nicknamed “Bloody Mary.”

Elizabeth I (1558-1603), Mary’s half-sister, found England on its knees and left it exuberantly reaching for empire. She made England unmistakably Protestant again, as it has been to this day. Her policy was to be “mere English”; she determinedly kept her people out of continental entanglements and gave them 30 years of peace in which to develop their resources—industrial, commercial, maritime and artistic. Then began a surge to empire: Elizabeth’s privateers, Drake and Frobisher, singed the beard of the Spaniard, Sir Walter Raleigh planted the royal Standard in the forests of Virginia, and England’s gallant little fleet repulsed the Spanish Armada. Elizabeth queened it over an age crowded with greatness, which nourished such figures as Shakespeare and Ben Jonson. She was the strongest queen and the most vital woman ever to rule England.

Mary II (1689-1694), daughter of James II, three-quarters of a century later acknowledged Parliament as the real ruler of England, thereby dissolving a long quarrel which had drained England’s strength and postponed its power. Already first lady of The Netherlands when called to England’s throne, Mary agreed to cross the Channel only if her husband, Stadholder William III of The Netherlands, could be co-ruler. Together, the two assumed kingship, making Mary the only feminine King in English history. Actually, Mary, a dutiful, intelligent woman who added a touch of respectability to a loose age, did little except serve and adore her stern, taciturn, unfaithful but capable husband. Like Mary I and Elizabeth, she died childless.

Anne (1702-1714), the younger sister of Mary, had the good fortune to rule in the era of one of Winston Churchill’s ancestors, the Duke of Marlborough, whose victories made England the strongest power in the world. A skilled diplomat as well as a great soldier, Marlborough led a Europe-wide coalition that broke the power of France. At the Peace of Utrecht, he won for Britain such imperial gems as Gibraltar, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Hudson Bay territory.

Anne also gave her name to an elegant era marked by Christopher Wren’s architecture, the Queen Anne chair, the thinking of Bishop Berkeley and Isaac Newton and the writings of Swift, Addison, Pope, Steele and Defoe. Personally she was a dull, respectable woman who spent most of her reign swathed in bandages to ease the pain of her gout and dropsy. She produced children but all died, leaving her the last of the royal Stuarts.

Victoria (1837-1901) had the longest reign in British history. After a lonely, over-protected childhood, she was awakened one night to be told that her uncle, William IV, was dead, and that she, at 18, was Queen. Three years later she married her shy, studious cousin, Albert of Saxe-Coburg, and bore him nine children, whose marriages allied England with the ruling houses of Germany, Russia, Greece and Rumania. In the first part of her reign, in the turbulent debates over the Reform Bill and during the unsettling changes of the industrial Revolution, she quarreled frequently with her ministers. As she grew older, and her Empire prospered and expanded, she came to exemplify Britain’s solid, enduring middle-class virtue, summed up in the word Victorian. When it came time to celebrate her diamond jubilee in 1897, Britain was at the summit of its imperial power and glory, and recognized in her the Symbol of its majesty.

It is a quote. TIME MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 18, 1952

No Comments