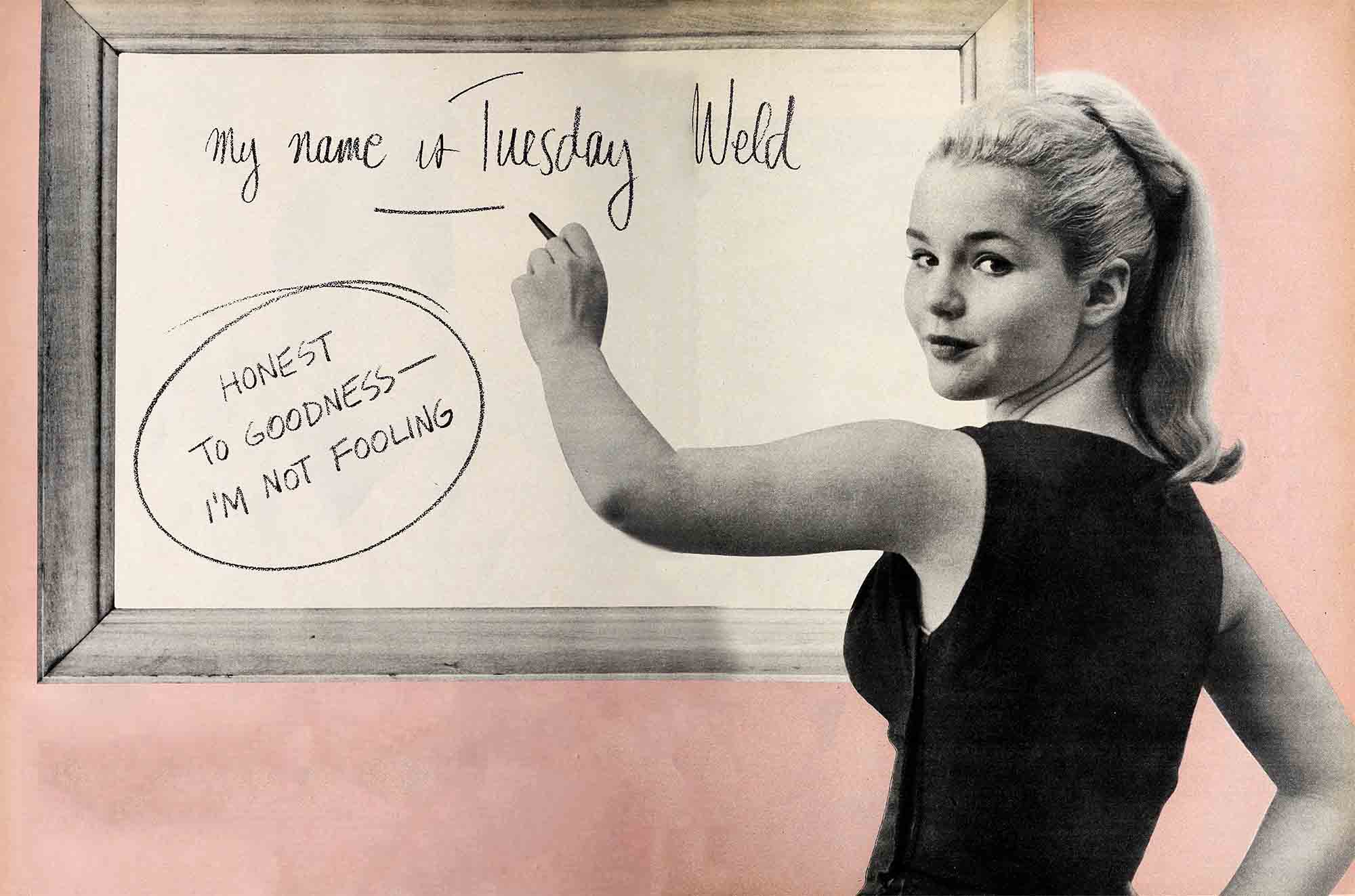

My Name Is Tuesday Weld

The day I enrolled at Hollywood High, I just knew it was going to happen all over again. You see, I’ve been to forty-seven different schools since kindergarten, although Mother insists it just seems that way and that I’ve really only been to six and had a whole series of tutors in between. But every time I go to a new school, or even to a new class in the same school, it happens.

The teacher smiles at me, trying to make me feel at home. Then she’ll ask, “What’s your name?”

I’ll take a deep breath and say, “My name is Tuesday Weld.”

“Yes, but what’s your real name?” she’ll ask, the welcoming smile just about gone now.

“Honest to goodness, my name is Tuesday Weld. Honest, I’m not fooling.”

AUDIO BOOK

Sometimes, the teacher just sighs, shrugs and tells me to take a seat, usually at the back of the room. Sometimes she asks for my mother to come and see her or to write her a note. And once, when I burst in upon the class in the middle of an algebra lesson that was going nowhere, the teacher handed me a piece of chalk. “If that’s your name,” she said, “go to the board and write it 100 times.”

I don’t really mind. I like my name. I come in for a lot of jokes but at least once I’m introduced, people don’t forget it.

I was named Tuesday, you see, because I was born on Thursday and had arrived two days late. Well . . . since my mother’s going to read this, the actual truth is my folks were expecting a boy. They’d already picked out a name, Rodney, after one of my great-grandfathers. When they found out I was a girl and they needed a name for the birth certificate, Mother said, “Put down Susan.”

As soon as I could gurgle, I called myself Tu Tu. Mother called me Too-Too because I was always getting into things. Somehow Tu Tu and Too-Too turned into Tuesday.

I was born on August 27, 1943—or was it 1941???—in a Salvation Army Hospital in New York City. It’s a very nice private hospital, so I’m told, and also very inexpensive. My being born was a financial problem for my family. My older sister Sally and my brother David, he’s six years older and Sally’s eight years older, were both born on a farm in Cape Cod, when Daddy was a stock broker and a gentleman farmer with 3,000 chickens. Just before I was born, he became very ill and he couldn’t work any more. My folks had to give up their farm and move to New York.

When I was three years old, Daddy passed away. I don’t remember much about him except from photographs—he was very handsome. He used to call me his “little social security card,” whatever that means! Daddy developed a serious heart condition which finally took him away from us.

Even when you’re very young there are certain things that you can remember about your life. For instance,I remember the place we lived in from the time I was born until I was nine. It was a cold-water flat on 53rd Street in New York, with the bathroom in the hallway and the bathtub in the kitchen. It wasn’t very nice but it was all we could afford. After my father died, Mother went out to work to support Sally and David and me. She got a job at Lord and Taylor’s department store, selling things. Everything she made went for rent and food and clothes for us.

Mother had a friend who was a designer and buyer at Best & Co., a New York department store. One day, when she happened to see some pictures that a photographer had taken of me for the family scrapbook, she told Mother I would make a good model and Mother agreed to give it a try. I was then just three years old. From my very first professional sitting I had fun. I liked looking into the camera. I posed for ad copy and fashion promotion for Best’s until I was about eight. Actually it was good for me, I was very shy as a child. Meeting people through my work helped me climb out of the shell I was in. I’ve been told I was the first child model who had a long blonde page boy, instead of tight corkscrew curls that most baby models had. I was known as the tailored type. Whenever dresses didn’t have any ruffles they sent for me.

When I was nine, Mother took us all to live in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, which worked out very well because I was tired of modeling then. Besides, I’d become unpleasingly plump which is not too good for photographing. Besides, David and Sally loved to swim and Mother wanted them to have a chance to take lessons with a good coach, By saving her money she was able to afford to take us. Sally and David really learned how to swim like champs. Matter of fact, David is in the Marine Corps now and he just sent us home a trophy he won for coming in third in a relay race in the All Marine Corps Swimming and Diving Championships.

When I was ten and a half, we moved back to New York. I enrolled in the Professional Children’s School and began modeling again and also doing TV commercials. Between times, I went to school, which was really a hassle—not school, but getting there.

My brother David was in charge of taking me every morning. We did not get along. In fact, I couldn’t stand him. People tell me this is normal. We had to take three buses, then get off and walk through Central Park to get from our apartment to school. I was awful hard to get along with and David didn’t help matters any. He used to tease me. We’d get on the bus and within two minutes we’d have all the passengers glaring at us. I’d scream at him at the top of my lungs and throw my lunch money under the seats, which he had to retrieve. Or else I’d wait until we got off the bus and toss my money in the street. I was such a sweet girl! Then we’d walk through the park and he’d begin teasing me and I’d cry. My sister and I didn’t get into fights much. In fact we weren’t particularly close. Eight years is a lot of difference when you’re growing up. Now Sally’s married, has two children and lives in New York.

Do you believe in fate and dreams? I do. I hope that doesn’t sound strange but I’m a Virgo (born between August 22nd and September 22nd) and that’s typical of us, according to some horoscopes I’ve read. From the time I was ten I used to have a dream that some day I would meet and get to work for director Elia Kazan. Even when I was ten, Mr. Kazan’s name meant more to me than any other in the profession. He had just directed “East of Eden.” When, soon after I’d had a small part in a picture made in New York, “Rock, Rock, Rock,” I heard that Mr. Kazan was casting for “The Dark at the Top of the Stairs,” a Broadway play, and that there were to be open tryouts. I flew at the chance.

The week before I was to appear at the tryouts I wracked my brain deciding what I should wear. Most of my wardrobe was—and still is—jeans and shirts and pullovers, but I had to wear something to impress Mr. Kazan. I couldn’t make up my mind which extreme to go to. Oh, yes, I had decided to go to an extreme, that was for certain.

First of all, I bought the highest high heels I could find. Then I found a bright pink sleeveless dress that I knew Mr. Kazan couldn’t help but notice, and to go underneath it, I bought a huge crinoline and taffeta petticoat that stuck out a mile and made a swishing noise when I walked. I even dyed my hair platinum. When my mother came home that evening, she nearly died! But it was too late to do anything about it. Next came some deep-tan makeup so that I would look outdoorsy and healthy even though the summer had already passed. To complete the picture, I bought some thick phony eyelashes that could have knocked six people down if they’d stood within a foot of me.

As I started to leave the house, I got cold feet. Had I gone overboard? I pinned on a hunk of false hair made up into a thick ponytail braid, and over it I tied a pink scarf—more like a rag—which I felt was sort of a “country” touch to balance things. Off I went to the theater.

When I finally heard my name called I could barely walk to center stage. I started reading. After a few minutes, Mr. Kazan called out and asked me if I would please go offstage and come down where he was.

“Young lady, how old are you?” My idol was talking to me and the words weren’t what I wanted to hear.

“I’m . . . I’m . . .” I mumbled something that sounded like sixteen. (I was really going on fourteen.)

“Well, then, can you tell me one good reason why you’ve made yourself up to look like a woman of thirty-five!”

Sitting there listening to him tear me apart, I was crushed. Then, in a flash, I realized I should be grateful that he cared enough to even waste time with me. I sat quietly and listened.

“First of all, that hair . . . it has to go. Get it back to its natural shade. And that makeup and those eyelashes! Miss Weld, you’re a mess! Another thing, that petticoat you’re wearing—I could hear you coming a mile away.”

He could see I was almost in tears, but he knew that he had to say what he did for my own good. I started to get up and he said softly, “I would like you to come back and read again.”

I nodded, too numb to speak.

“All right, Tuesday, I’ll expect you back next week.”

One week later, in flat shoes and minus war paint, petticoats, false hair and bright pink dress. I read again for Mr. Kazan. That was only the beginning of the “hurry-up-but-wait” routine connected with Broadway tryouts. I came back to read again off and on for nearly three months. Finally, I was given the part of understudy to the two lead ingenues. Maybe if I was lucky one of the girls would get sick—not that I wished them harm—only some minor ailment serious enough to allow me to make my Broadway debut! I was so happy I cried with excitement. I was going to work for Elia Kazan!

Opening night I sat backstage listening to two other girls saying the words I knew by heart. Since I was only an understudy, I didn’t have a dressing room and, between acts, I found a seat on the steps in the basement. There I was, dressed in black and in a blue funk when a man came over and introduced himself. I’d been reading movie magazines practically all my life and I knew immediately that this tall, young, handsome man was the Dick Clayton, former actor turned agent. The man who’d helped discover and develop stars like James Dean and Tab Hunter. He was very nice to me. He asked me why I looked so sad, and I told him it was because I would never get a chance to act in the play and that I was utterly miserable.

There was something very soothing about him and his voice. He asked if I had an agent. I said yes. I did at that time. Then he said the most exciting words I’d ever heard:

“Tuesday, you don’t belong in a basement sulking. You belong out in Hollywood. You should be a star.”

I just nodded and he continued.

“If you ever decide to come to Hollywood and you need an agent or help and advice, let me know.” He gave me his card.

In April of 1958 Mother and I sat down and had a long talk about things. The agent I had in New York wasn’t able to do anything for me and I was too impatient to just sit and wait for things to happen. Mother agreed that perhaps I would have a chance if we went West. Then she said, “But, Tuesday, going to Hollywood is expensive. We’ll need money for transportation and clothes and we’ll have to find a place to stay; there’s no guarantee you’ll find work right away.”

I knew it wouldn’t be easy but I said, “Mother, why don’t we talk to Mr. Clayton? He seemed so kind. Maybe he’ll help us.” Mother agreed. We sent Mr. Clayton a wire and asked him to call us.

Two hours later I heard the operator say, “Hollywood calling.” Dick Clayton was on the wire. Mother and I talked with him and told him we wanted to come West but that we were poor and didn’t know how we could manage it. Mr. Clayton said, “Leave everything to me. I’ll see what I can arrange and call you back in a day or two.”

He called us back a day and a half later with a guarantee of a job—an appearance on “Matinee Theater” on TV. “Can you leave tonight?” he asked. “You start work tomorrow morning!”

I’ll never forget the night we arrived at the Los Angeles airport, April 18, 1958. When I get nervous I eat a lot, especially sweets, which doesn’t help my usually size-seven figure. I hadn’t realized how I’d been gorging myself until I got off the plane. Mr. Clayton took one look and said, “My gosh, Tuesday, you’ve grown into practically Wednesday!”

Then I realized I’d put on about ten pounds since he’d seen me. On the way to the hotel, where Mother and I spent the night, Mr. Clayton told me about the part I was to play on TV. Then he handed me a slip of paper with the name of a doctor. “I want you to take off some weight,” he told me. “But don’t make yourself sick starving like some kids out here do. Go to this doctor and have him give you a sensible diet.”

With Mr. Clayton’s help, Mother and I found a tiny furnished apartment in a section called the Sunset Strip. On a clear day, if you lean out of our front door far enough, you have a view of the whole city!

People ask me what I’m like and what I like. It’s not really easy to be objective about yourself, but as near as I can tell I’m not very difficult to sum up. I’m 5 feet, three inches tall. While my natural shade of hair is honey blonde, right now it is lighter, a sort of gold and silver blonde. I weigh between 110 and 112—that is, when I stay on my diet. I love sweets, go on candy and cake binges every once in a while, but I’m usually content to drink coffee, black, munch on grapefruit, drink hot lemon and water (ugh) and fill up on proteins and salads without dressings. When I go off the wagon, I like to cheat like mad—maybe five thousand calories at one sitting—then I can go without sweets for weeks.

I’m pretty moody. I don’t know why, except I seem to be very high or very low, being “middleish” is not a frequent occurrence. I am still a little shy underneath, but now I handle it differently. When I was young I’d go off by myself or hide in corners at parties. Now I’m a big extrovert, which is only an introvert who has learned how to cover up his insecurity.

As I said, people call me kooky, which I guess means I’m a character. I hope they mean it in a nice sort of way! I hate anything routine; it bores me to get into a rut, which is why I flit from thing to thing. I have never been able to make too many close friends, my friendships, like my hobbies and interests, go in spurts. I love to paint and play the piano and read books on art. I’m crazy about all kinds of music from Rodgers (Jimmy) to Rachmaninoff (Serge). I love to go horseback-riding, dancing and my idea of a good date is if I don’t have to dress up.

One important lesson I’ve learned is that if you laugh at yourself other people will laugh with you and not at you. As I said, I’m a pretty moody kid. In order to help get myself out of moods I change cosmetics, like different shades of lipstick and most of all I like to fix my hair different ways. I have several full wigs, plus a lot of false braids and extra hair, in assorted colors, that I use whenever I need a lift.

So when Timmy Evert (he had one of the leads in “Dark at the Top of the Stairs’’) took me to the opening of the play “The West Side Story,” and then to a swanky party at the Ambassador Hotel, I decided to wear a chignon. Before going out I’d secured my false hair with enough bobbie pins to keep it in place for a year, or so I thought. During the evening someone requested the orchestra to play a polka. It was fun. Soon everyone got into the spirit of the music. Timmy started whirling me around faster and faster until all of a sudden I could feel my billion bobby pins coming loose . . . I tried to slow down. Have you ever tried coming to a halt during a full gallop? That’s the way it was with the polka—we just kept whirling around. Next thing I knew I felt something tickling my shoulder- out of the corner of my eye I saw it—my hair—hanging limp, with the bobbie pins falling all over. I tried to say something, but Timmy kept twirling me around. The music was so loud, he couldn’t hear me ask him to stop. We kept going until we were the last couple left on the floor. All that motion made me dizzy. Next thing I knew, I was falling; before I could stop myself I’d slid clear across the slippery dance floor. My chignon, which now looked like a rag mop, flew in the opposite direction! The music stopped. Everybody was watching me. Timmy helped me up. I held my head high, smiled at him and said in what I hoped was a dignified tone, “Excuse me, I think I’ve lost my hair.”

With that, I strolled casually across the room, stooped down and picked up my chignon. Then, walking back across the floor, I said, “I’ll only be a minute, Timmy.” I laughed and, hair in hand, headed for the powder room. As I walked away, I could hear the others laughing, but laughing with me, not at me!

It’s very hard to put your whole life down on paper, but I hope you know me a little better after reading this. If I haven’t said it before, I must mention that everyone out in Hollywood sure has been great to me. I hope I can stay here for a long time. I think I’m making some strides. When I first started working in pictures, I overheard Leon Shamroy. the cameraman on “Rally Round the Flag,” tell someone I looked like Jayne Mansfield’s sister—”from the rear.” At least that means I’m making some progress. I can’t wait until the day I look like a grown-up glamor queen from all directions!

—AS TOLD TO MARCIA BORIE

TUESDAY’S IN 20TH’S “RALLY ROUND THE FLAG, BOYS” AND WILL SOON BE SEEN IN “THE FIVE PENNIES,” PAR.; “SAY ONE FOR ME,” 20TH.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1959

AUDIO BOOK