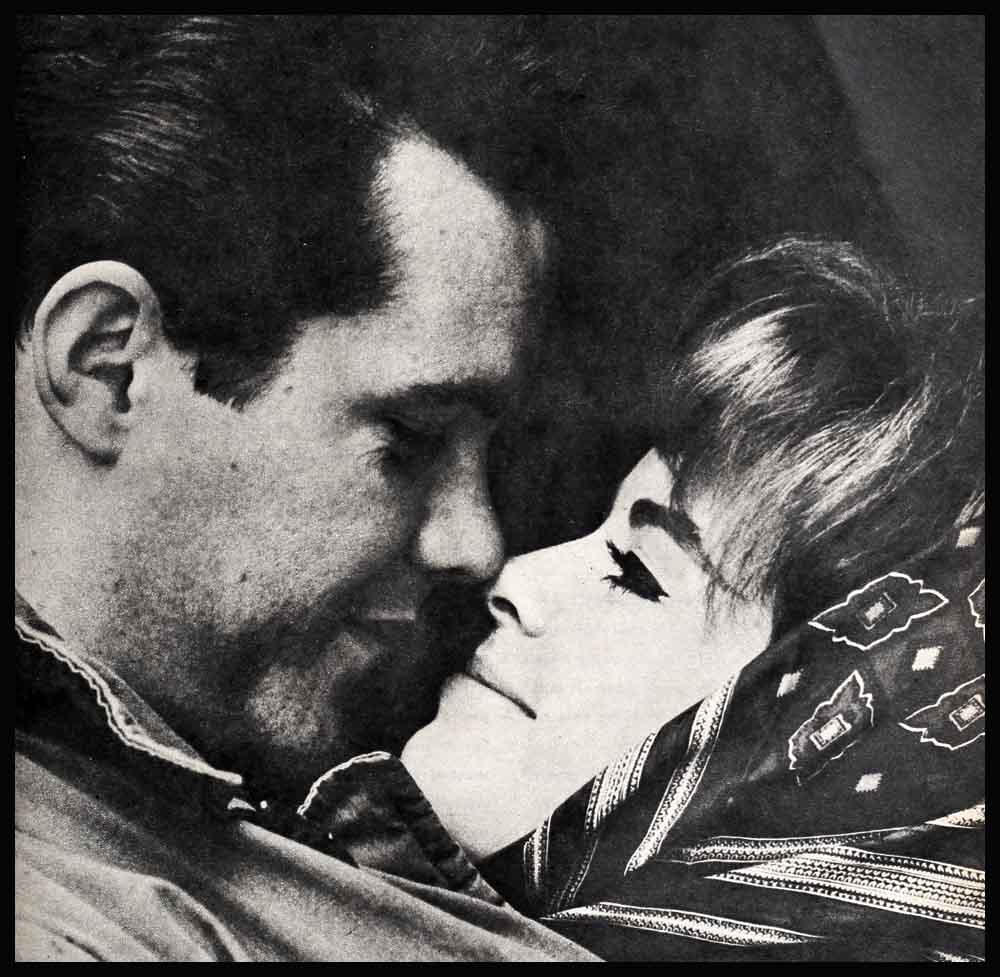

Deborah Walley Tells!

Two months from now, I am going to have a baby. It’s still very hard for me to believe I’m pregnant. For hours, I forget about it— then, suddenly, I have to reach for something and I remember—my body is different now. I’m pregnant.

It would be a lie to say that I’m not frightened now. Every woman is frightened. Because other women can tell you a hundred things about having a baby, but it’s not you. They’re not talking about your baby—the baby you think you might name Jonathan Antony Ashley.

I frighten easily, and I’m afraid of the pain. I’m afraid of not knowing what is going to happen. Sometimes I’m even afraid of the hospital. The last time I was in a hospital was when I was born. I’m afraid of the anesthetics that make you talk too much. And I don’t know what I’ll say.

But being afraid is only part of it—a little part. Sometimes I just kind of stand there in front of the mirror in awe of everything. İn awe of the unbelievable fact that I’m about to be a mother.

We didn’t plan to have a baby now. We didn’t plan anything because—secretly—we were both afraid we couldn’t have children. We only admitted that to each other after we learned I was pregnant; and then we wondered if everyone who really wants children is afraid of not being able to have them. Even now—months later—I still get amazed with myself, amazed that I’m able to do this incredible thing!

For a long time I wouldn’t even believe that I was pregnant. I thought that something was wrong, that I should see a doctor to find out if something was wrong. But I didn’t dare to believe I was pregnant. İt was John who looked at me—really looked at me—one morning and said, “Debbie, you’re pregnant!”

The next day—Saturday, September 22—I took the test. The results would come on Monday morning. John would telephone the laboratory at 10 A.M. and then he would call me at Walt Disney Studios where I was making “Summer Magic.” There were things to do that weekend and we did them, but all we really did was wait for Monday.

John’s voice was funny when he finally called at 10:30 Monday morning. Cold. Negative.

“Debbie, I have bad news.”

That was the first moment I realized how much I wanted a baby.

“What is it?”

“The rat died. They’ll have to make the test again and we won’t know til tomorrow morning.”

I was surprised to find myself laughing. “Out of all the rats . . .”

Then John was laughing, too. “Out of all the rats in the world . . .”

“My rat had to . . . die!” And we laughed together on the telephone, knowing that in a few minutes we were going to stop laughing and start waiting—again—for Tuesday.

On Tuesday he telephoned me at 2 P.M. and said, “Darling, the rat’s still out to lunch.”

An hour later he called back again. “We won’t know until tomorrow morning. They weren’t able to get another rat.”

And on Wednesday morning he phoned once more. All he said was, “Darling, you’re a mother.”

I don’t know what pregnancy does to other people. For the first five months of our marriage what I felt most was an enormous relief. We had wanted to be married for so long and we had waited for what seemed to me so long, and now we were married. Then we found out that I was pregnant. Knowing that we are going to have a baby hasn’t brought us closer. From the start— even before our marriage—we were so close that nothing could make us closer. But knowing about the baby has enhanced things. It is as though there’s a halo around everything now.

And it has changed us. Nothing about John is quite the same as it was a few months ago.

He still teases me. “I’m getting a piece of candy,” he will say, as innocently as if he didn’t remember the craving I have for chocolate now. Oh, such craving.

“Can I have one, too?”

“Of course,” he’ll half-whisper, slurring the words together. “But it’ll make you even fatter than you are.” “John. what did you say?” And he’ll look puzzled that I didn’t understand. “I said, ‘Of course! It’ll make you happier than you are.’ ”

What a tease!

But his teasing is gentler—much gentler —now. It used to be a game for John to needle me and not to stop even when I got angry. Just as it used to be his right to be served dinner. We usually watch television while we eat, and I would set the tables and trays up in the kitchen and then carry them into the den. The night I discovered I was pregnant I started to carry them into the den as usual.

“Sit down, Debbie,” John said. ‘I’ll bring your dinner.” And he has brought my dinner ever since.

John’s different in a hundred ways. More than anyone I know, John hates to waste time. To him, wasting time is symbolized by shopping for groceries. The two or three times I asked him to go to the market with me I could watch him getting furious at having to push his way through aisles jammed with shopping carts and then having to spend fifteen minutes standing in line.

One night last week he came home late.

“You’re late,” I said. “It must have been a very long interview.”

He started to take bags of groceries out of the car. “I was at the market,” he said casually—too casually. “I did the week’s shopping for you.”

We own a wild, huge, monstrous, while Standard poodle named Hondo. Even before I was pregnant, I was a little afraid of Hondo. He jumped on me and knocked me down half a dozen times. Once he bolted around a corner and skidded into me. I fell and sprained my ankle.

I guess if John and I fought about anything, we fought about Hondo. “John, if you don’t do something about this dog . . .” I would say. But John never did.

“He’s a man’s dog, Debbie. You’ll have to get used to that.”

John liked Hondo wild. He was proud Hondo was a man’s dog, rough and tough. Yet the day after he learned I was pregnant, John took Hondo to an obedience school—to tame the wildness that he so much loved.

Sometimes now John will come Over to me and—with incredible wonder and excitement in his voice—will say, “I can’t believe, I still can’t believe, we’re going to have a baby.” John is sure the baby will be a boy. And yet . . . “Maybe it will be a girl,” he says suddenly. Or “Debbie, we can’t buy things for the baby, not even a crib. How will we know what color to get?” He’s afraid to touch me, afraid to hug me too tight. “I’m afraid I might hurt the baby,” he says.

And in his gentleness he’s even stronger than he was before. He’s even stronger when I need his strength.

Six weeks ago I thought I was going to have a miscarriage. I suppose I had been expecting something to go wrong, because my family doesn’t have babies easily. My mother had two miscarriages before I was born and one afterwards. Both she and my grandmother had to have their children by Caesarean operations; and my doctor has already told me I should be prepared for that possibility.

I was crying as though the world had ended as I lay on the bed. And I suppose I thought that my world had. “I knew it would happen. I knew it would happen.”

John telephoned the doctor. The doctor told him that all we could do was wait. Then John sat on the bed beside me.

“It would be horrible if we lost the baby, Debbie. But if you’re going to miscarry, there’s nothing you can do about it. Getting upset won’t help. And it might hurt.”

I still couldn’t stop sobbing.

He forced me to look at him. “Listen to me, Debbie,” he said. “I don’t think you’re going to lose the baby. I do not think you’re going to lose the baby.”

And all of a sudden I could begin to relax.

It was only later that he told me, “I was scared too, Debbie, but I couldn’t let , you guess it.”

If my pregnancy has changed John, it has also changed me. Last August 12, I was twenty-one years old. I get funny little shivers when I realize that on my twenty-first birthday I was already pregnant—although I didn’t know it. Legally, I became a woman last August 12. I had the right to vote and the right to order a drink. Yet I didn’t feel much older that day than I had felt the night before. It’s only now that I feel I am a woman, really a woman. Because, on April 30, 1963—two days after my first wedding anniversary—I am expecting a baby.

“How awful for you,” a few people have said. “To ruin your figure when you’re so young. To be tied down.” Then j they add, “And it certainly won’t help your career.”

I look at them and think, “How awful for you that you don’t understand.”

My figure will be changed; my career will be changed. But I don’t want to be a teenager forever. Never to grow up—that’s what I think would be awful. I want to be a woman. My clothes are all too tight now and I’ve lost my waistline and I feel proud when I walk down the Street. Everybody looks at me and smiles; and I smile back. Pregnancy is one great big continuous moment of niceness. Even the nausea that I felt for a month and the headaches that still come at 5 P.M. every afternoon don’t spoil the niceness. Each headache only reminds me that I am going to have a baby.

There is one thing, though, that I regret about this pregnancy. In all the romantic movies I’ve seen, the wife puts on her most beautiful dress and serves her husband a gourmet dinner by candlelight. Then—when he is drinking his demitasse—she leans forward and whispers, “Darling, we’re going to have a baby.”

I’m not sure this could ever happen in a modern marriage where the husband must guess almost as soon as the wife does. But at least I wish I could have told John the results of the test Over candlelight and wine. Instead of him telling me. And without candlelight and wine, at that.

I’ve already decided—next time it’s going to be different.

—THE END

See John in “Hud,” Paramount. Debbie is in Walt Disney’s “Summer Magic.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1963