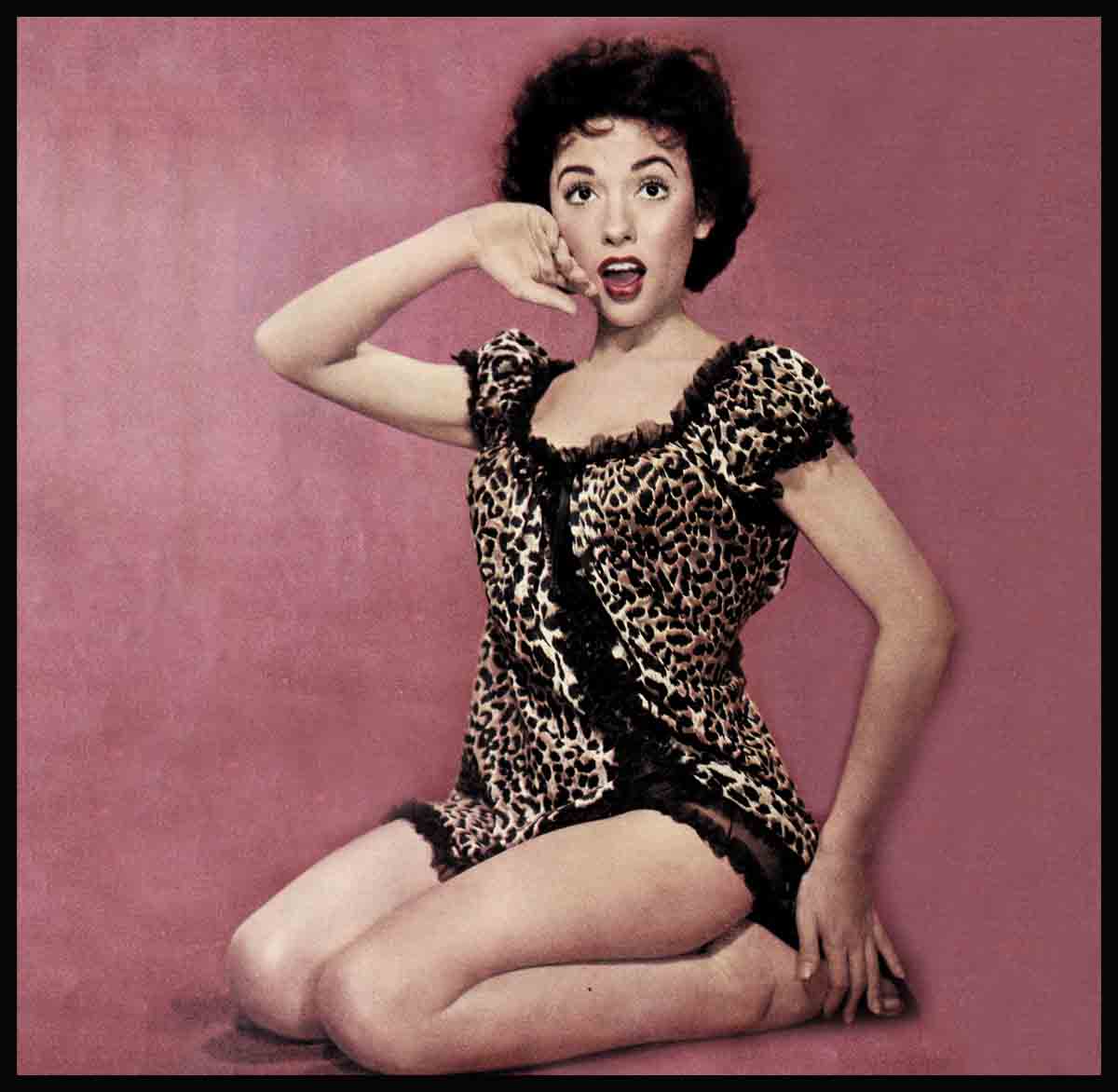

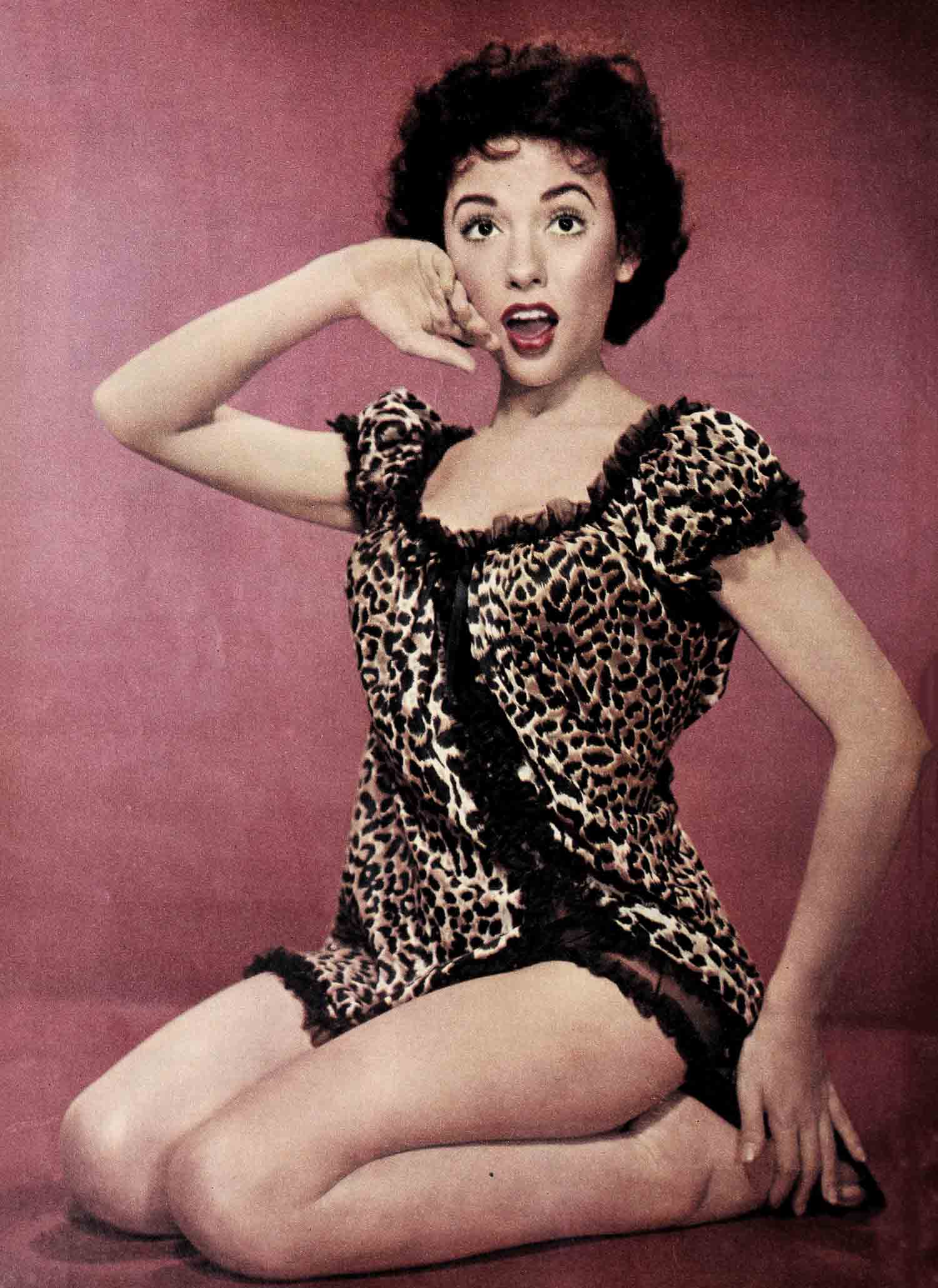

Barefoot Girl With Chic—Rita Moreno

Relaxing over coffee in the dining room of the house she shares with two other girls, vivacious Rita Moreno was gaily recalling her latest experiences at Twentieth during the making of “The King and I.”

“The prop boys have repainted my chair on the set,” she was telling her housemates, Louise Martinson and Florence Mitchel. “Remember the one I had during ‘Untamed’? On the back was painted ‘Rita Moreno?’ Now it says, ‘Rita Moreno’ with no question mark, and they’ve drawn a hunk of dynamite under it. On the seat they’ve painted an exploding mushroom and a ‘POW!’ And yesterday before I got in, the hairdressers and wardrobe girls wrote ‘Good Luck and Happy Days’ across my dressing room mirror, with a star by it. Then the prop boys put a big gold star on my door. Aren’t they wonderful?” bubbled size-eight Rita, her eyes sparkling with happy tears.

It was Sunday and the girls were catching up on each other’s doings of the week. Louise Martinson, who has roommated with Rita for five years, is a beautiful blond from Boston, and her claim to fame is being the only combination female disc jockey and news commentator in the country. Florence Mitchel is a lovely up-and-coming TV and film actress. Rita Moreno, beautiful fiery Latin, has her toes firmly gripping the top rung of the stardom ladder.

There was an air of contentment and fulfillment in the room. Huge bullfight posters looked down from the walls at the remains of.a hearty breakfast and coffee cups were being filled for the tenth time. Breakfast had started at 10 A.M. and it was now 2 P.M. The girls had hashed over their dates and doings and given advice only when asked. (This is one of their rules of living together and liking it.) It was monthly rent time, so they had all forked over $58 apiece. And they had filled the weekly food kitty with six dollars each, plus ten. About every three weeks, it takes ten extra dollars apiece to restock the diminishing larder for three healthy appetites. Rita had given Louise her weekly admonition that she must stop hiding her beautiful face behind a microphone and do a television show. Now they were deeply engrossed in Rita’s tales of Twentieth and the making of “The King and I.” As Princess Tuptim, Rita’s career has begun to zoom, and the girls were caught up in the excitement of having their belief in Rita proven. Rita was smartly dressed in gown and robe, the subtle scent of White Shoulders perfume lingering around her carefully done hair and bright face. Rita is definitely chic, but a peek under the table proves she is also barefoot.

Being barefoot, on screen and off, is very natural for Miss Moreno. In movies, she has played guttersnipes of every nationality. As an Indian, Latin or Mexican, she has invariably: 1) lost her man; 2) gotten killed; 3) watched her man get killed; or 4) taken a running high dive off a cliff—mostly barefooted.

“I had a run of deaths for a while,” muses Rita. “I died in my very first picture, ‘So Young, So Bad.’ In fact, I did everything many an actress dreams of doing in that picture. I was beaten violently; my hair was shaved off against my will in reform school; I was almost psychotically afraid of people; and I ended up hanging myself. That was in 1949, when I was seventeen. I wish I had a chance to do it again now.”

When Rita was seventeen she had been in show business thirteen years and had been a professional since she was nine. Her mother’s sacrifices, plus Rita’s determination and belief that she would catch the brass ring, began when she was four and started dancing lessons with Paco Cansino.

“Mother and I were alone,” Rita explains. “Like most Puerto Ricans who move to New York, we lived with another family and had only one room. Mother worked as a seamstress in factories. I remember when I caught chicken pox and we had to move out and find another place. When Mother took me to kindergarten, I didn’t know a word of English. The more the teacher tried to make me feel at home, the more hysterical I got. It was one of my most frightening experiences. Somehow, Mother saved enough to give me dancing lessons, and she sewed for me. I remember my tremendous desire to own nothing but beautiful clothes.

“It became a mania,” Rita continues. “I would have daydream fantasies. I’d stand at the windows of the best stores and pick out things. I’d dream I was a princess and I could have everything I wanted. It was a wonderful game,” Rita says dreamily, “and I suppose it helped me keep my determination to be a great dancer. Something helped because I was a thin, frail, sickly-looking child—all hair and great big eyes. I was anemic and had constant chest colds. Mother stuffed me with iron tonic and cod liver oil every morning until I was fifteen. When I was nine, I was in the hospital for a year. They thought I had trichinosis, a fatal disease that affects the muscles. Every day at 2 A.M. they would wake me up and take a blood test. I didn’t die, and they never found out what was wrong with me. I went right back to dancing. I sometimes wonder how I lasted through all those dance routines. I’d walk up a flight of stairs and be as tired as an old lady of ninety.”

But Rita stubbornly and deliberately did strengthening exercises. She was always hanging from the top of a doorway or window—stretching. She forced herself to overcome her lethargy and be quick and active. And she danced constantly, building her muscles and her talent in a fiery desire to rise.

“When I was eleven I got a real dancing job,” Rita continues with a twinkle, “at Macy’s department store. They opened a Little Theatre in the Toy Department. The show opened right after school, so I was constantly rushing from 181st Street to get all the way down to Macy’s by 3:30 P.M. I had to put my make-up on in the subway. A day didn’t pass that at least one indignant little old lady clucked, ‘Shame on you, wearing make-up at your age!’ I danced at Macy’s for three years and seven hundred and seventy performances.”

At thirteen, Rita was cast in a Broad- way play—as an actress. The play was called “Skydrift,” and it lasted three days, but the food was good. Rita played a young daughter who sat consuming spaghetti at the dining table. (It was in this role that she realized she liked ham in her spaghetti.) It was during the mother’s dramatic scene when she thinks she sees her son who was killed in the war. On opening night, dark-haired, button-eyed Rita was gulping down her spaghetti and grinning like a banshee at the audience. The audience went with her and, instead of serious silence, laughter filled the theatre.

“Scene-stealing was explained to me in very firm tones by that actress when we finally got off stage,” Rita recalls. “She really racked me out. It’s just as well the play folded. I was eating so much on stage I would have been as fat as a tub of lard.”

But that play and the constant radio commercials and occasional dramatic parts—mostly as babies and youngsters—made a big impact on Rita. She realized she wanted to do more than dance . . . she wanted to become an actress.

“I promised myself that I’d be in pictures before I was eighteen,” Rita says thoughtfully. “By then I was getting good roles on radio, like Bernadette and Fatima, on The Ave Maria Hour, but still doing baby gurgles for commercials. I hated night clubs, but I realized they were the only way up. So at fifteen I started. I soon learned that Spanish dancing is not for clubs. The patrons are looking for razzama-tazz and oh-you-kid. All my nightclub dates were out of town except for one week at Leon & Eddie’s, and some weekends in a Bronx club. But I couldn’t always convince my bosses that I was twenty-one. The couple that owned the Bronx club were sweet. They treated me like a daughter. When the authorities would come into the club to check up on minors, they’d lock me in the girl’s room or throw a fur coat over my shoulders and put me at a table with my back to the door, so I’d at least look like a ‘mature woman’ of twenty-one!

“I learned a lot in those clubs,” Rita says quietly. “I met everything from sugar daddies to young punks. I began really observing human nature without realizing it. I met some fine people, too. I learned to look past the surface into people. Quite often the cynical or wisecracking person is hiding a wonderful nature behind a facade. I learned not to make quick decisions, to wait. I think the main thing wrong with the whole wide world and particularly the people in it is lack of understanding. If we take a little time, listen with honest interest, anyone will be happy to drop the mask and let you really know him.

As Rita struggled doggedly through the rugged night-club circuit—doing her classical Spanish dances and listening to the applause going to the sophisticated or slapstick comedians—it would have been easy to become bitter. But Rita didn’t have time. She was experiencing life, taking from it just what she could use and ignoring the sordidness surrounding her. At seventeen, she was that combination of age-old wisdom and wide-eyed innocence that is the best possible product of poverty. It would have been easy to have let poverty be the excuse for failure. But poverty only gave Rita the overpowering desire to rise above it. Her personal promise to be in motion pictures before she was eighteen suddenly became a possibility.

“Paul Henreid was casting for his film, ‘So Young, So Bad,’ in New York,” she recalls. “I got the script and read it. I never wanted a part so badly. I thought I’d die if I didn’t get it. When I auditioned for Mr. Henreid, he’d never seen or heard of me. I had a four-page scene which built up to complete hysteria. I did it so intensely that I couldn’t stop crying after it was over, and I look awful when I’m crying. My eyes and face swell up and get red. I had to go to the girls’ room and bathe my face in cold water. That was the audition. I did the same scene for the screen test. Both Mr. and Mrs. Henreid were wonderful to me. He seemed impressed with my test.

“Then I waited. I lost weight. I was a mass of nerves. Mother and the neighbors said novenas for me. I wasn’t home when the call came, so Mother took the message. She knew if she told me before dinner, I wouldn’t eat a bite. So she put it off. But looking at my miserable face she couldn’t wait any longer. As I was taking my first bite, she told me Id gotten the part. I started to cry. Mother started to cry. It was the happiest blubbering I’ve ever experienced. Suddenly,” Rita says quietly, “the big doors were open. I knew I could walk through them. Mrs. Henreid told me later that she had prayed I’d get the part.”

During the picture, Paul Henreid worked and helped Rita constantly. His kindness, advice and confidence were responsible for an inspirational performance from the diminutive actress. Today, people who see this picture on TV are amazed to find that the seventeen-year-old actress gave her best performance in her first picture.

It was the next year that a talent scout spotted Rita in the play, “Signor Chicago,” with Guy Kibbee. After a two-hour talk with Louis B. Mayer, Rita was on her way west, holding a stock contract with M-G-M and an even stronger belief in the open door policy.

Fourteen barefoot, fiery Latin parts later, Rita walked out of Twentieth’s wardrobe department attractively clothed, in smart high heels and a wiggle. She was costumed for her role in “The Lieutenant Wore Skirts.” In this, she had four pages of dialogue in which she impersonated Marilyn Monroe. It’s incongruous to watch the petite, brown-eyed brunette imitate the sultry blond to the point where you devoutly hope everyone else realizes it’s all in fun. Rita’s role is strictly comedy in this—and she gets her man!

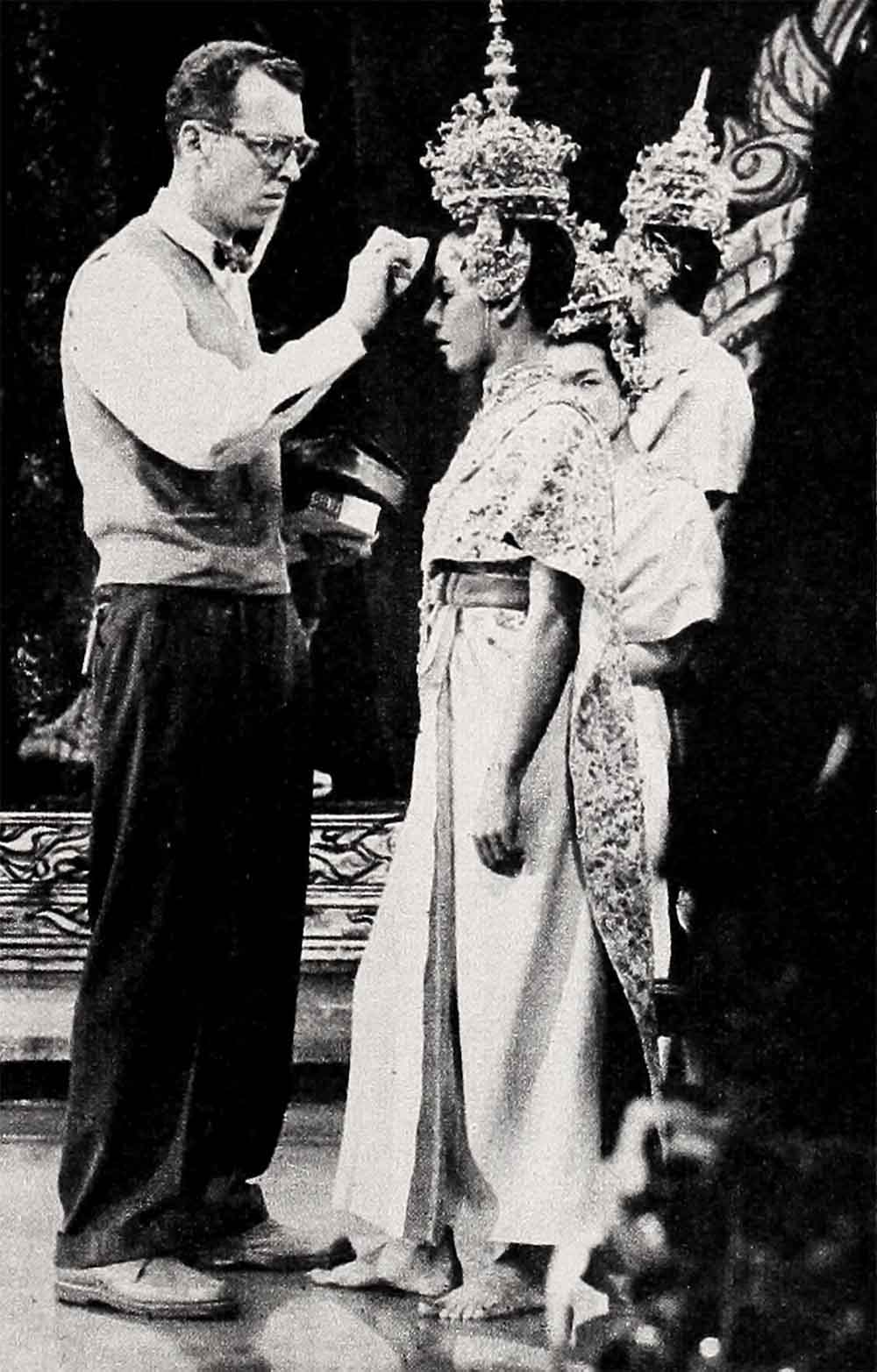

Which brings us to Princess Tuptim in “The King and I.” Rita is back unregretfully flat on her feet, playing the romantic young lead and dressed in the dream clothes of a Burmese high-caste girl. It is a delicate, refined and gentle role. It includes two wonderful duets and the narration of one of the most delightful ballets of American theatre, “The Small House of Uncle Thomas.” Rita wears 24-carat gold dresses encrusted with pearls and diamonds—and wears her gentle, loving heart on a gold lamé sleeve. As “The Lieutenant Wore Skirts” has proved her a fine comedienne, so the role of Tuptim will show the depth and dimension of her dramatic ability.

After twenty-four years of living and twenty years of working, Rita has matured into an uncomplicated girl with a solid foundation of basic values, moral integrity and level-headedness. She could easily afford a more expensive place to live now, but she’d rather enjoy the responsibility and companionship of sharing a home. Since coming to Hollywood, Rita has been bombarded with date offers from the perennial bachelors whose names appear constantly in e columns. She doesn’t date for publicity—only for fun. And no one has more fun on a date than Rita. She enjoys the people she’s with. She loves Scrabble, charades, any game. If she can’t enjoy people, she’d rather stay home, read a good book, watch television or just talk to her roommates.

“I enjoy dating,” Rita explains with enthusiasm. “I like to date the kind of men I can learn from. When I first came out here I dated Hugh O’Brian, who now plays the famous Wyatt Earp on television. Hugh asked me to go horseback riding with him. Most men would back out when a girl said she didn’t know how. Not Hugh; he taught me. It’s lucky he did. A month later, I was cast as an Indian girl and, although I didn’t do Hugh proud, I at least stayed on the animal. There were ten of us that had to ride past the camera and into the woods. There was a cowpoke just out of camera range to stop my horse for me. When the director signaled, my horse took off at a full gallop going like the wind. I was clutching the saddle horn and screaming at the top of my lungs, ‘Ho, already, yet!’ We sailed past that cowpoke so fast, the breeze we whipped up nearly floored him. If it hadn’t been for Hugh’s teaching, I wouldn’t have made it out of camera range right side up,” Rita laughs.

“Jeff Hunter is another good friend that I’ve dated. He is a fine actor with a real goodness of character. He taught me the value of friendship and how to be honestly friendly with others. Then Rich Egan taught me the wonderful antidote for bitterness—faith. Rich is a fine man, with faith in God and faith in mankind, including himself. He did bit parts for six years before he made the grade. The other day a producer came up, slapped him on the back, and told Rich he always said he’d make it. Rich didn’t think it was phony. He reasoned that producers in town hadn’t been wrong—he hadn’t been ready. They didn’t close the door in his face. They gave him bit parts and helped him learn his craft. Bitterness gets you nowhere, that’s something Rich taught me.

In a way,” Rita says thoughtfully, “when I date, I’m looking for all the traits and qualities I want in my husband. The most important quality to me will be thoughtfulness. I don’t like callous men. Cynical men, however, are usually bitter, and with patience they soften and become real. One fellow I know is intelligent, really brilliant, and at twenty-six is trying to be an intellectual cynic. I like him as a friend, so I took the time to break down his defenses. He’s wonderfully warm and outgoing with me. He’s still cocky with others, but never with me.

“I do want to get married, and I want two or three children—but I want it to last forever. I think it’s silly to say I want a tall, dark and handsome man who’ll bring me flowers and candy every day. He can be short, fat and bald, if he’s the right one. I think a lot of girls get a mental image of a physical man and are blind to real love when it comes along.

“I want to get married, but I don’t know if I’m ready,” Rita says honestly. “But I’m willing to try. I realize the tremendous responsibility you have to be willing to take on. I guess I won’t know until I experience it. But I do know this: there is nothing like a man to love.”

Rita is strongly aware of the many things she still has to learn and experience. Honest and natural, she wisely cannot say what she would do in a circumstance she has not experienced. She doesn’t know whether she would give up her career for marriage. “Why anticipate, it might not be necessary?” She doesn’t know where she’d like to live permanently. That’s partly up to her future husband and partly up to the traveling Rita plans to do. She is not impatient—just aware of the transitory period she is living in.

During this period Rita is busy and happy. In her spare time she oil-paints waste-baskets, sews pearls and beadwork on sweaters and skirts, reads Hemingway, Wylie and Faulkner (in a weird mood). Her secret passion is the ancient love letters of “Heloise and Abelard.” An incurable romantic, she can sit and cry by the hour over the tragic love poured into their letters. Rita cries from her toes up, and laughs the same way.

She went to a neighborhood movie with her roommate the other night. The Tom and Jerry cartoon had all the audience laughing, except for Rita. The silly cat was chasing a poor little duck and Rita cried through the whole cartoon. Her roommate was laughing so hard at Rita, she missed most of the cartoon.

Rita’s sense of humor is just as strong and unexpected as her tearful reactions. One night, Louise and Florence were sitting up late listening to music. It was midnight and Rita should have been in bed because of an early studio call the next morning. Suddenly, Rita bounced into the living room, appropriately attired and did a hilarious burlesque on a burlesque. Her impersonations are great. As the gum-chewing burley queen, she had the girls in stitches and it was quite late before the animated pixie retired. She may have hated herself in the morning . . . but she couldn’t resist her playful impulse.

Rita has no temper, but she is temperamental. In the five years she’s lived with Louise, she’s lost her temper only twice. When she is hurt or unhappy she withdraws quietly, usually heading for the patio outside her first-floor blue and white bedroom. When she has worked out the mood, she rejoins the human race. She does not have extreme moods often. Generally, she is fun and easy to live with. She is warm and vital and mad about children. Sensitive and shy, she nevertheless stops mothers on the street with babies and peeks into carriages to ooh and aah. She adores her seven-year-old half-brother, Dennis.

“That one,” she grins. “Yesterday he said very seriously, ‘Nanny, can I do just one show business with you. I’ll be very good.’ Dennis watches a lot of television, has studied the mandolin and is now on the accordion. I think he means it! Mother and Dennis live out here, but Mother is very wise, she will not live with me. She won’t let me help her financially, either. But she is so proud of me.”

Rita is impulsive and emotionally generous. On one of her days off, while shopping in Hollywood, a woman and her nine-year-old girl came up and asked Rita for her autograph. The child was a real fan. She told Rita how much she loved all her pictures and then named them. The woman and child were from the Middlewest. Impulsively, Rita asked them if they’d like to have lunch with her at the studio next day. Of course, mother and daughter loved every minute of that lunch in the commissary with the stars, and Rita was as thrilled as they, for she enjoys other people’s enjoyment.

Rita has her eccentricities, however. When she’s working, her bedroom looks as if a cyclone had struck. She can’t throw away old fashion magazines: they pile up for two or three years. Finally, in despair, Louise will suggest getting rid of them. Rita will look at the cover of an oldie and say, “Oh no, this one has just what I want in it.” Louise has given up the struggle. Since the house is large, Rita has many nooks and crannies to fill.

Rita also has a mania for earrings and fancy shoes. She has more of both than she could ever use, but she keeps buying them. High-heeled strappy affairs make her happiest—naturally, she kicks them off the moment she gets a chance.

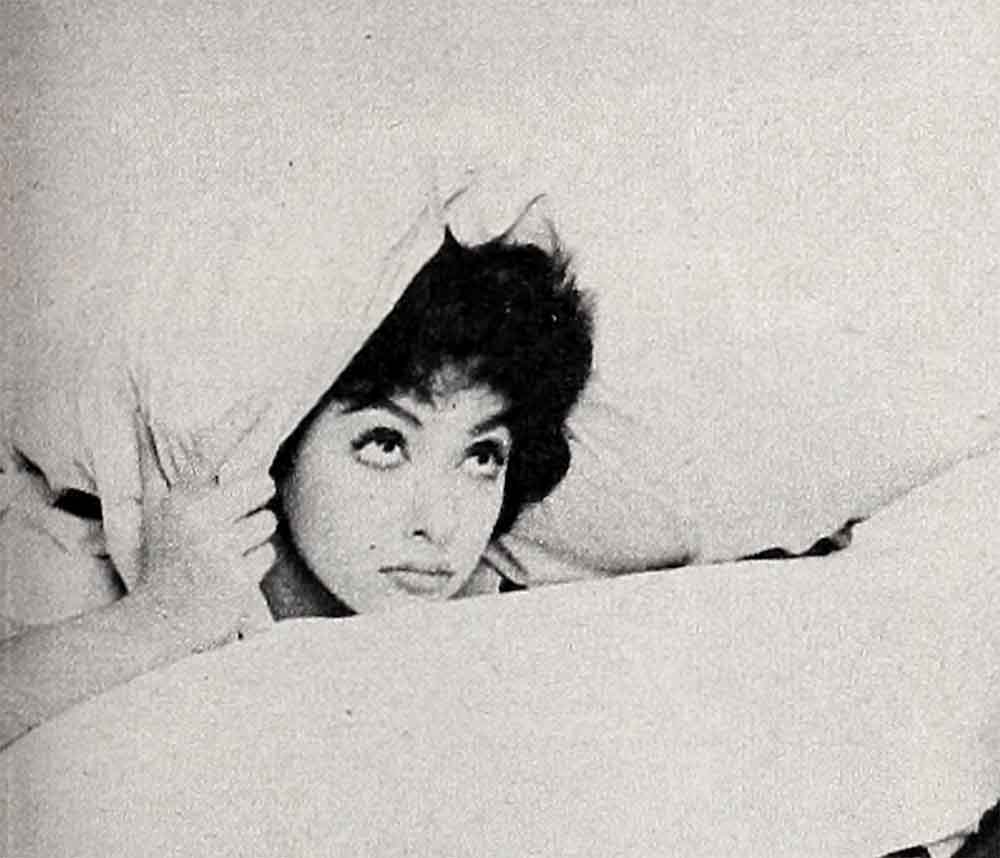

Rita is not a happy waker-upper. It takes quite a bit of time after the alarm goes off before she manages to grunt answers so her roommates will know she’s not dead.

In the winter, she wears absolutely mad, crazy flannel pajamas—bright red, leopard, gaudy colors. In the summer, she switches to shortie pastel nightgowns of nylon and lace, rhinestones and ruffles with panties to match. And for both seasons she gets all gussied up to go to bed. She takes almost as much time getting ready for bed as she does dressing in the morning. The face and hair must be just right (she has a strong feeling about creaming arms, legs, and back), and her last nightly ritual is to liberally douse herself with White Shoulders cologne. Upon retiring, Miss Moreno is ready for an unexpected fire in the night.

Five years ago, when Rita and Louise started sharing an apartment, Rita couldn’t boil water. Now she specializes in Italian concoctions and blintzes. She loves to mess with spices and herbs and come up with variations on a recipe. They have a huge old stove with two ovens, a broiler and a warmer. They promised each other never to eat in the kitchen or on trays—thus the constant use of the dining room. They love to eat by candlelight . . . they love to eat.

“There were four of us,” sighs Rita drolly, “but we lost one. She got married. But even now when her husband is out of town, she comes over and stays with us. We have a good system. We agreed in the beginning that any beefs should be brought right out in the open. We also agreed to keep our noses out of each other’s dating. Of course, that doesn’t stop us from making a big fuss when the phone rings at dinner time. It’s silly, I guess, but we sit and make loud noises, appropriate comments and suggestions. We also have a system for locking the door at night. There is a lamp near the door and we leave it lit with a note under it. As we come in, we put down ‘Rita is here,’ then ‘Louise is here,’ and the last one in locks the door and turns off the light. Phone messages are very important, so we put them on a toy airplane that’s in front of the door.

“We’re worse than parents about being late,” Rita admits. “One night, one of the girls went out on a date and by three in the morning we were up worrying and stewing about our errant child. She came in at five. The car had broken down and she hadn’t thought of calling. So now if anyone’s going to be unusually late, they call in so the others won’t spend the night pacing the floor and getting ulcers.”

Rita’s immediate interest in others and their problems is, perhaps, one reason she is so well loved on every set she’s ever worked. On “The King and I” set, electricians, grips, hairdresser, stars and producers called her Princess with honest affection. The reaction of workers on the set is a dead giveaway to a star’s real personality. These people are fully aware of Rita’s warm vitality, talent and sweetness.

It wasn’t too long ago that a thin, big-eyed child stood in front of dress-shop windows in New York daydreaming a fantasy. “I am a princess and I can have everything I want.”

Today, Rita Moreno is treated like a princess and is playing the role of a princess. Granted, a barefoot princess—but with chic. She is living, breathing proof that daydreams do come true.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1956