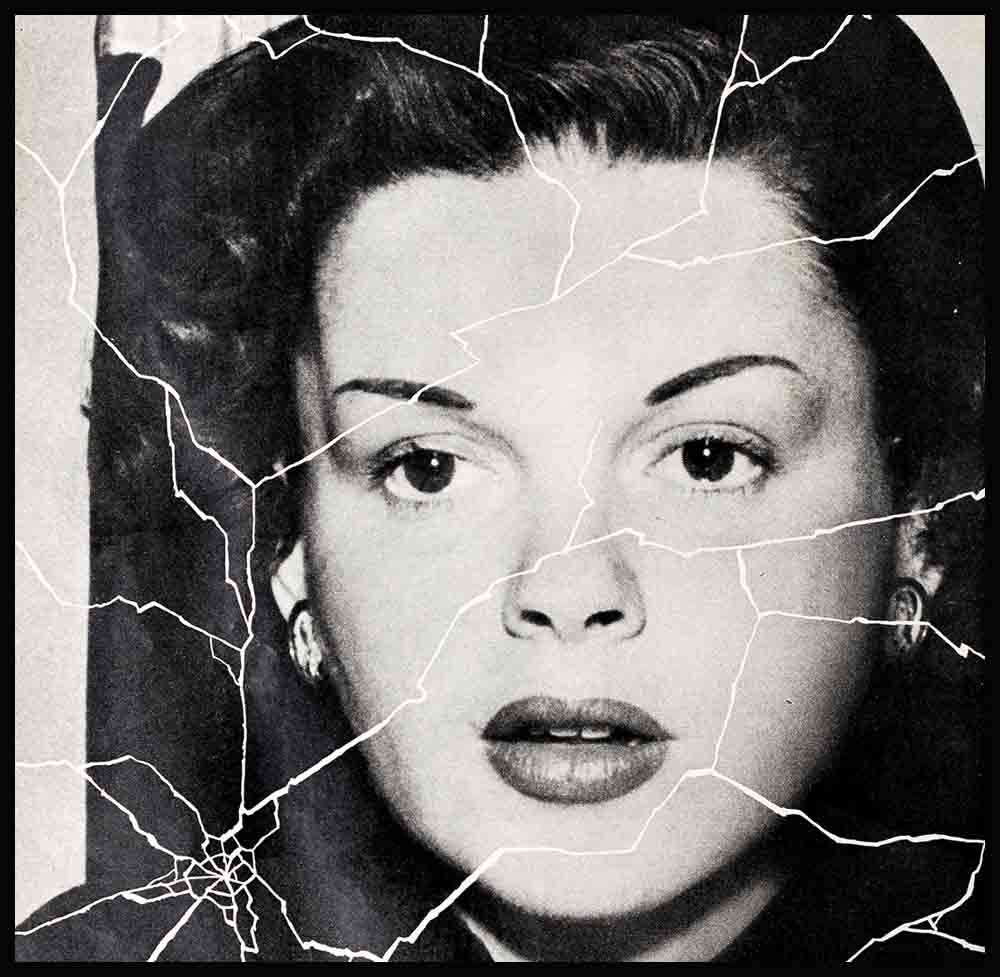

Crack-Up

This is the unforgettable story of the crack-up of one of the greatest talents in show business—told in its entirety and told for the first time. It’s the story of how Judy Garland went broke on a hundred thousand dollars a year, lost her faith in family and friends—and found it again when she learned to have faith in herself.

A close friend of Judy Garland’s recently described her as a cracked plate, still useful but dangerously near the end of its service.

This is the story of the cracks in the plate, of how an exceptionally talented young lady experienced a crack-up of all values, a crack-up she scarcely knew about until long after it occurred.

It is not a pretty story. Some of it has been told before, but no one has ever understood how the gradual building up of tensions, each small within itself, can lead to the crack-up of a great talent.

AUDIO BOOK

There is no real beginning because, like the slow, studied dripping of water on stone, tension takes a long time to make an impression. The pressures are always there, because all life is a process of breaking down, but the big blows—the ones that breed nightmares and insomnia and headaches and sessions with psychiatrists—don’t show their effects all at once.

The powerful blows are the ones that come from within, like the time Judy was only ten years old and a member of the Gumm Sisters vaudeville act. The family lived in Lancaster, California, a small town where Judy’s father managed a movie theatre.

Every weekend Mrs. Gumm gathered up her three girls, took them to Los Angeles and put them on-stage for as little as fifty cents per girl per performance, then brought them back home to Lancaster.

“I always felt like a freak in Lancaster,” Judy recalled recently. “We were show folks.”

Once, when a major charade was being planned, Lancaster social leaders called on the Gumms, borrowed their professional costumes, admired the girls—but didn’t invite them to the party. Show business kids were all right as entertainers but not as social equals.

That was the first time Judy Garland was made aware she was “different.” It was not the last.

When she was twelve her mother and father separated. Judy was the baby of the family—she was even called Baby—and the apple of her father’s eye. She never understood why he left her.

When she was thirteen Judy enrolled at Hollywood High School. A vice-principal who was to be one of her teachers came over and said, “People like you should not be allowed to go to school with normal children.”

In those days Judy was as round as a ball, with just as much bounce. She was pretty, with large brown eves, a farm-fresh complexion and a puppy-dog personality. She was, she believed, as normal as blueberry pie, certainly as normal as any other little girl of thirteen.

What do you say to a teacher who tells you you’re not normal, don’t belong with normal children?

Judy said nothing. But she was so upset she never returned to the school. Instead she enrolled at a private school with other “professional children.”

Dorothy Gray, a child star in those days and Judy’s best friend, remembers her as Baby Gumm, the prettiest girl in her class, popularly conceded to be the most talented.

“Judy and I did all the things little girls like to do, from making fudge to roller skating,” Dorothy recalled. “But whenever we went to the movies we had to leave our names at the box office in case we got a studio call.

“There were a lot of things we couldn’t do, like take regular vacations or go swimming, because we might miss a film call or catch cold.

“We theatrical kids used to be embarrassed when our pictures were in the paper because the other—normal—kids we knew would tease us. I guess in a way we were robbed of childhood. Only two or three of the whole group we grew up with and worked with haven’t turned out as drunks, neurotics or bad-check passers.”

Judy’s father died the year she was signed by M-G-M. Her mother, Mrs. Gumm, was then put on the studio payroll, and began to use the studio as a disciplinary threat in place of Judy’s father. This was to have a lifelong effect on Judy’s emotional make-up and to color all her later relationships with M-G-M.

“You behave, Judy, or I’ll tell the studio on you,” Mrs. Gumm would say. Judy became afraid of “the studio,” the place where she spent most of her waking time.

“There were thumb screws inside me every time I walked on the lot,” Judy said recently, recalling those years.

“The atmosphere at M-G-M was one of terror. My life for a time was full of fear. Going into the studio was like going to a haunted house every day.”

What was it like to have a major motion picture studio for a parent? If one incident can be cited as an example of a blow from within, here it is:

Judy made twelve pictures in her teens. She had to dance, cry and act before the cameras, in addition to singing. Like all professional children under contract to a major studio, she also had to sandwich in six hours of school every day.

The only thing Judy could do that she liked was to eat. At every meal she stuffed herself with all the food she could cram in, sneaked in double malts between scenes, nibbled on chocolate bars at school—and gained weight. Finally an M-G-M executive sent for her.

“You look like a hunchback,” he told her. “We love you but you’re so fat you look like a monster.” Judy tried to smile through the tears, then ran. At the time she was called a monster she was violently in love with Clark Gable.

After this incident a humiliating directive was sent down from the front office. No matter what Judy ordered for lunch she was to be given only a small bowl of consomme. The studio’s attitude is completely understandable. They had a movie star under contract, a movie to be made, millions of stockholders’ dollars tied up in it. They were completely sympathetic with Judy’s emotional problems—problems which she tried to solve with the temporary relief of overeating. On the other hand, Judy had contracted to make a picture and the picture had to be made.

From then on lunch time became a cruel game for Judy. Hungry from working hard all morning, she would go to the studio commissary, sit at a table by herself and order a full meal. The waitress would take the order, then return with a bowl of broth. Judy would smile bravely through the tears and sip her lunch. She always ate alone.

And, while sipping her lunch, Judy more than once would overhear someone in the commissary point her out as “that little girl they were stuck with when they let Deanna Durbin go.”

Judy was famous and a star but she was miserable. A friend described her as a “toy money machine which could be wound up and set to work in the morning, turned off at night, and put on a shelf just like any other toy. She was never treated as a person.”

Once, Judy’s older sister, Suzanne, brought her small daughter out to the p studio for lunch. “Isn’t it wonderful?” said Suzanne. “I’d like my little girl to be a movie star, too.” Judy almost screamed at her. She pounded the table and yelled, “I’ll break your neck if you ever bring the child to the studio again!”

That was one of the first indications that the pressures were forcing a crack in the pottery of Judy’s personality.

Judy’s friends insist that she never wanted to be a movie star at all. She merely wanted to sing. But from the beginning Judy’s pictures were big spectacles, requiring long rehearsals and recording sessions, dancing and acting as well as singing. Judy threw herself completely into everything she did. Even in those days she was a perfectionist and gave it everything she had.

A director who knew her then said, “Judy should have done just one scene a day, then taken an ambulance home.”

Once, while doing a dance routine, she almost collapsed. “I’m so tired and I’m so hungry,” she gasped to the director. He replied, “Do this routine again and you’ll forget you’re hungry.”

Judy got tired from overworking and undereating. To keep herself going she started to take a stimulant called Benzedrine. Then she had to take sleeping pills to counteract the Benzedrine and let her sleep, then more pills to wake her up. Judy says of this time, “I lived on bolts and jolts.”

The sleepless nights and hungry days began to have a telling effect on Judy. She became nervous, irritable and ill. One day she didn’t show up for work and the entire studio was in an uproar. For the first time in her life Judy began to realize that she was something of a personage. She was genuinely ill, but she found that people considered her illness “temperament”—a not unusual occurrence in Hollywood. Though annoyed, people really began to pay attention to her, and Judy began to bask in the realization that she was, at long last, important.

Coupled with the weakening of her physical structure she had discovered a test which enabled her to learn if people really cared for her. Like a child who thinks herself unloved, Judy began to kick up her heels just to assure herself that everyone loved her.

A psychiatrist would call this an infantile regression, a search for the affection she missed as a child. The diagnosis would probably be accurate. After her father’s death Judy spent most of her time searching for the affection and attention that the corporate entity which had, to all intents and purposes, become her parents was unable to give her.

The crack was getting larger.

By the time Judy was sixteen she had become a singing workhorse. She threw herself into every production with her whole heart and body and as a result was burned out after every picture. Between pictures she rested by reading scripts for her next one.

“They never gave me a rest,” she complains now of those years. “I went from picture to picture. They would promise me a six-month vacation, but after I had been away a week or two they would call me back again.

“I’d start a new picture, then break down. There would be rows and suspensions. We would try to straighten it out, but when I went back to work the whole thing started over again.”

We must remember that Judy’s studio was faced with the fact that they were dealing with an emotionally sick and exhausted person—one who refused, like the fighter she is, to lie down.

By now, Judy was beginning to realize that her life was no longer her own. Even worse, she earned $5,000 a week, later $150,000 a picture, but had nothing to show for it. Her mother had been appointed guardian of her money, but most of it was spent as fast as it came in. How much was spent on legitimate living expenses for Judy and how much might have been unnecessary extravagance is something that was later to be investigated through legal procedures. Meanwhile, all Judy had to show for the large sums she had earned was a small trust fund which the courts had insisted be put aside.

Judy exhausted herself trying to keep up with Mickey Rooney, the Whiz Kid of movies. She became a big star herself with “The Wizard of Oz.” In 1939, when “Oz” opened in New York, she went with Mickey to make a personal appearance at the Capitol Theatre.

They broke records doing six and seven shows a day at forty-five minutes a show, with only forty minutes between each appearance. One day, as they finished the act and went off stage, Judy collapsed in the wings. She had been working too hard and too fast without letting up.

Judy had hit emotional high gear. It was at this point that she met David Rose, the composer and orchestra leader. He was serious, preoccupied and older.

Everyone in Hollywood has a theory about why Judy married him. Most people think it was rebellion against work Some say she thought orchestra life would be more Bohemian and fun. Judy says simply, “He was good to me.”

The marriage was short; it lasted only four years. As compensation for her unhappiness Judy again turned to food. M-G-M rightly insisted she lose weight. Extreme in everything she did, Judy took to starvation diets of black coffee and cigarettes which, coupled with work, exhausted her even more. The answer: more stimulants, more sleeping pills.

By 1945 Judy was no longer employable. She was world-famous, hungry, sleepy, divorced and unhappy, and she , held up productions, a Cardinal sin in Hollywood. She dropped out of “The Barkleys of Broadway” and was replaced by Ginger Rogers. That night she stayed at ; M-G-M, crying in her dressing room, protesting that no one loved her.

But a week after her divorce from David Rose she married director Vincente Minnelli. This marriage lasted on and off for nearly six years.

Suddenly Judy began to have a strong feeling that she must be alone, that she didn’t want to see any people at all. After her daughter Liza was born she was in a weakened condition, and her prodigious appetite left her for the first time. She lived on nervous energy and doctors’ prescriptions.

When Hedda Hopper visited her on the set of “The Pirate,” Judy took the columnist into her dressing room and went into a frenzy, saying everyone was against her, that she had no friends. After that she began to fail to show up for work—and was suspended.

She pleaded with M-G-M to let her work, so they gave her “In the Good Old Summertime.” She finished it on schedule and the studio rewarded her with its biggest picture, “Annie Get Your Gun.”

The director, Arthur Freed, had been with Judy in the old days, but she demanded he be replaced. The nerves and exhaustion were showing again. She recorded her songs, then started rehearsals. One day at lunch hour she went home and didn’t return. The studio announced that she had been suspended and Betty Hutton was signed to replace her.

Judy was broke, off salary and jobless. She was convinced nobody cared for her.

She was twenty-seven years old when the first big crack appeared. A person can crack in many ways: in the head, in which case the power of decision is taken away from you by others; in the body; or in the nerves. It was Judy’s nervous reflexes that gave way, the result of too much work and too many tears.

Now the studio once more assumed the role of parent. Louis B. Mayer, head of M-G-M, sent her to Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston and paid the bill. Carlton Alsop, the man Judy calls “Pa,” recalls her convalescence: “I used to take her out for trial runs, to baseball games, to see how she reacted. Then, I’d take her shopping. There was always a car handy, so that if she had a relapse we could rush her back.”

While in Boston, Mr. Alsop took Judy to a little summer theatre. When the word got around that she was in the audience, the cast asked her to join them in a farewell party backstage. Judy accepted. After the paying customers had gone home the cast serenaded Judy from the stage, then asked her to sing to them.

She turned to Mr. Alsop and asked, “Pa, do you think I have any voice?” He told her she still had the best voice in show business. He told her to try singing. She did—and sang for forty minutes.

“Judy found she hadn’t lost her voice,” Mr. Alsop recalled. “It was medicine she couldn’t get in the hospital.”

Judy stayed in the hospital eleven weeks, at last started to sleep regularly, and gained weight.

Then the studio called her back for “Summer Stock,” produced by Judy’s old friend, Joe Pasternak. Again she was “too fat.” In addition, she wasn’t well enough to be working, but she needed the money and the studio needed her, so she raced to reduce before going back on the set.

To help in the dieting Judy once again started on pills—first to reduce, then to help her sleep and forget the pangs of hunger. One day she failed to show up for work and was threatened with suspension. She was told there were three million dollars riding on her and that she was being temperamental and selfish. Studio people were given orders to watch her every minute. A specialist was flown out from Boston to be in readiness on the set “just in case.”

Somehow Judy finished “Summer Stock” and, although promised a vacation, went right into “Royal Wedding.” This one she never finished. One Saturday morning she failed to show up. The studio called four times and was told she was on the way, but she never left home. The studio suspended her and announced Jane Powell as her replacement.

In the presence of four friends, including Mr. Alsop and her husband, Vincente Minnelli, Judy tried to cut her throat. It was a feeble attempt, but to Judy it represented something.

She said, “All I could see ahead was more confusion. I wanted to black out the future as well as the past. I wanted to hurt myself and everyone else.”

Judy had reached the bottom of her emotional reserve. She had mortgaged herself physically and spiritually. But the response of her fans was amazing. She received hundreds of telegrams from fans wishing her well. The only one she saw was one from Freddie Finkelhoffe, the songwriter, who said, “Dear Judy. So glad you cut your throat. All the other girl singers needed the break.”

Mr. Alsop, who received the wire, took it in to Judy. She laughed hysterically at it. “They still love me, don’t they,” she said to Alsop.

Katharine Hepburn came by while Judy was convalescing and delivered a long speech about how important Judy was, not only to herself, but to those to whom she had brought so much pleasure.

Judy listened quietly and then made up her mind to get back on her feet. “I grabbed my daughter, Liza, and moved into a seven-room suite at the Beverly Hills Hotel,” Judy recalls. “When we had been there a few weeks and I thought they might start asking about the bill, I packed a couple of cases, dashed down to the desk and told them I had just been called to New York and would they save my suite for me.

“It was a big bluff, but they never thought to question it. We flew to New York and I did the same thing there. Of course it was mad, but it was the first real fun I had had in my life. I had worked like a dog and I was broke—but I was beginning to be happy. I was free.”

The crack in her personality was being mended.

In New York Judy did all the things she had never been allowed to do before. She stuffed herself with food, went window-shopping, went to bed and got up when she pleased.

The long-term contract with M-G-M was dissolved at Judy’s request. This left her alone, separated from her mother, who Judy felt had let her down, and on the verge of divorce from Minnelli.

Her reputation for unpredictable—and expensive—behavior was so widely publicized that no producer wanted to take a chance on her.

Judy tried to run away from herself and Hollywood by going to Europe, where she ate herself into obscurity. When she returned to Hollywood a year later, all washed up at twenty-eight, she met Sid Luft at a party. It was Luft who suggested she regain her confidence in herself by opening at the London Palladium.

Then Judy began the weary trudge on the long road back. If there are pressures which can crack, there are also incidents which can heal. Sometimes the person is the stronger for having broken and been patched together properly.

On the night of April 10, 1951, when Judy Garland opened at the Palladium, she began to patch herself up. Here for the first time is her story of that night. She said:

“The night before the opening I didn’t sleep a wink. I was terror-stricken. At daybreak I was pacing up and down my hotel room, almost out of my mind with panic and fear. I kept rushing to the bathroom to vomit. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t even sit down.

“When they finally got me to the dressing room I was only half-conscious. I hadn’t worked at all for almost three years, and had given a show in public barely once or twice since I was a kid.

“There were only minutes left. I had to get hold of myself. I said to myself, ‘What’s the matter, you dope? If you don’t cut this out you won’t be able to sing. Don’t worry. They won’t eat you.’

“Standing in the wings, waiting to go on, I became paralyzed. My knees locked together and I walked on like a stiff-legged toy soldier. And after a while, without knowing how it had happened, I found myself, not standing on the stage, but sitting on it. It was said I tripped over a wire or a loose board. That’s not true. I didn’t fail at all, really, I just collapsed.

“The fall happened after I had sung two or three numbers. I was trying to take a bow. I just went ‘Ugh’ and sat down. I sat there and thought, ‘Damn this.’ I looked up at Sid, who was hanging out of a box, screaming, ‘You’re great, baby, you’re great!’

“Somehow I got back on my feet, lurched back to the wings. I remember thinking, ‘That’s it. Judy falls on her can and that’s the end of the great comeback.’

“I was ready to quit, but my old friend Kay Thompson was waiting at the side of the stage. She screamed, ‘Get back there. They love you.’ Then she gave me a hug and a shove that carried me back almost to the center stage.

“Instead of giving me the bird, those wonderful British people clasped me to their hearts. I unlocked, and everything I wanted to do came surging out. all the bad years went. It was like being reborn. It was like being given a new life to start all over again.”

Later that year, Judy brought vaudeville back to the Palace Theatre in New York. She was overweight again and, naturally, she collapsed from overwork. But she rested a few days and returned to enjoy a record-breaking run of nineteen weeks. Night after night, audiences called out the old refrain, “Judy, we love you.”

Sid and Judy brought the show to Los Angeles and another tearful, thrilling triumph. That spring she and Luft were married.

At long last it appeared that Judy had lived up to the words of her most famous song. Somewhere, over the rainbow, she had found happiness. The happiness was short-lived.

Judy’s relations with her mother broke into court. Her mother had married a man named William Gilmore, whom Judy did not admire. It has also been stated that Judy felt her mother had mishandled her finances.

Mrs. Gilmore went to court to complain that Judy would not support her. She took a job as a sixty-dollar-a-week clerk at Douglas Aircraft. Judy’s friends, who recall that Mrs. Gilmore was a first-rate piano and singing teacher—she taught Judy, among others—thinks she took the job just to embarrass her daughter.

Judy’s daughter, Lorna Luft, was born December 8, 1952. Less than a month later Judy’s mother fell dead in a Los Angeles parking lot.

Judy, who had thought she was better, cracked like an old plate when she heard the news. For two years she was “in sanitaria”—her term for psychiatric treatment. She did no work, saw very few people. When she finally emerged it was to make “A Star Is Born” at Warners.

Hollywood biographer Cameron Shipp notes that she “approached this as fearfully as a child in the dark.”

“She was terrified,” said Sid Luft. “She hadn’t made a picture in nearly four years. She thought she was through, washed up, all over again. That’s why she made that picture so difficult.”

And difficult it was. Cary Grant, who was all but set as Judy’s leading man, was replaced by James Mason; five cameramen and four costume designers walked off or were fired from the job; a musical arranger left in a huff; the set was closed to the press for most of the shooting; the budget, first estimated at $2,000,000, was more than doubled; and the picture had the longest consistent shooting schedule of any picture in recent Hollywood history.

Judy said little other than that she is a perfectionist, George Cukor, the director, is a perfectionist, and so is Sid. “We had to have it right. We had to take time. Of course, there were rows and friction. There is in every picture that’s worth anything. We all did our share, but I was the bull’s-eye in the target and everybody aimed straight at me.”

When the time for the 1955 Oscars came around, everyone was certain Judy would get the Best Actress award for her performance in “A Star Is Born.” She did not. Grace Kelly won it for her work in “The Country Girl.”

A few hours before the award was announced, Judy was in the hospital giving birth to Joseph Luft, her second child by Sid. Everyone said her failure to win the Oscar would crack her wide open—for once and always.

Surprisingly, it didn’t. Somehow Judy had repurchased the spiritual and physical mortgage she had given in exchange for stardom as a child. At last she had inner resources to draw on. One such resource was humor.

With mime and words she tells of the hospital scene the night she found out she hadn’t won the Oscar.

“Just picture it,” says Judy. “There I was, weak and exhausted after the battle to bring Joe into the world. He wasn’t in such good shape, either; at that moment doctors didn’t give him better than a fifty-fifty chance.

“I was lying in bed, trying to get my breath back, when the door burst open and in came a flock of television technicians. I already had a TV set, but they dragged in two more huge ones. I asked what they were for and they said that after I got the award I would have to talk back and forth to Bob Hope, who was emceeing.

“They strung wires all around the room. They put a microphone under my nightgown. They frightened the poor nurse to death when they told her, ‘If you open that window while the show is on we’ll kill you.’

“Then they built a four-story-high tower outside the hospital, for cameras which were to focus through the window. What with all the excitement and everything, they got me all worked up, too. I was flat on my back in bed, trying to look cute.

“I was all ready to give a performance. Then Bob Hope came on the screens and said Grace Kelly had won.

‘I’ll never forget it to my dying day. The technicians in my room said, ‘Kelly! Aah,’ then started lugging all the stuff out again. You should have seen the looks on their faces as they tramped out with all that gear. I really thought I would have hysterics.”

Sid had brought three bottles of champagne and a dish of caviar with which to celebrate with Judy after she had won the Oscar. When the TV men had gone he said, “How do you feel?” Judy said, “Disappointed.”

That night they sat alone, sipping the champagne and eating the caviar. But Judy remembers the night with a smile and that has a twinkle—not hurt—shining through.

Judy seems at long last to have learned to live with herself. That doesn’t mean she has become people-broken and docile. She still is a perfectionist, who insists on absolute perfection in everything she does. And, she still needs to know that everyone loves her.

In September, 1955, for example, while she was rehearsing for her first television appearance, the director, Paul Harrison, called all of the technicians into a huddle. He told them about Judy. “She’s a child,” he said. “If you mention that her nose is shiny she’s likely to walk off the set and not go on at all. Be careful of everything you do and say around her, but remember that she’s one of the greatest talents any of you will ever work with. For the next four days keep that in mind and love her. If you do nothing else, make her know you love her.”

Despite the pep talk, rehearsals for the show were not all smooth. Judy came late, keeping three color-camera crews idle at $1,200 an hour. It took six hours to film two 20-second promotion teasers for the show, which normally should have been done in fifteen minutes. Even on the day of dress rehearsal, Judy was forty-five minutes late.

But the ninety-minute Ford Star Jubilee for CBS-TV had the largest viewing audience ever to watch a spectacular. For CBS-TV, the end justified the means. And that, to a large extent, is the story of Judy’s professional life.

Ever since she was a child, people have put up with Judy’s erratic behavior because they believe talent is a law unto itself. And as long as she continues as one of the world’s great attractions she’ll be judged by a unique set of rules.

Last summer, Judy completed a five-week run at the New Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas, where she made her nightclub debut. She was paid $35,000 a week, while the hotel paid an additional $20,000 a week for the orchestra and other acts. The previous high for an entire show had been $50,000 for Liberace. Judy insisted on being the highest-paid entertainer. Her thinking was, “if they want me they’ll have to pay me,” and the fact that they were willing to go so high proved to her that they truly did want her.

As always, she missed performances and made irritating demands of the hotel proprietors, but she brought in large enough crowds to give the hotel a profit.

Judy wanted to play in Las Vegas for the most elemental reason. She said, “I have to get money to pay off back taxes.”

Despite the fact that she is one of the world’s greatest entertainers she is almost broke. Although the Lufts live in a big home, it is virtually unfurnished; for a big star Judy has a remarkably small wardrobe; and she and Sid have no money in the bank. Today, all Judy has to show for sixteen years at M-G-M is a scarred psyche, a paid-up $100,000 insurance policy and a pitifully small income from the one investment left over from her childhood.

Even without material things the Lufts seem happy. Their entire home is planned to permit their children—Lorna, 4, Joseph, 21 months, and Liza, 10—to have freedom to play. The extensive outside grounds are covered with playground equipment and children’s toys. There is no swimming pool because it would be a menace to the children.

“We haven’t bothered to furnish the house completely,” Judy says. “We believe the house should grow with us. We aren’t through growing yet and neither is the house. If I have my way (despite doctor’s orders) we’ll have a few more kids around. It’s children, not furniture, that make the home.”

In her home Judy is as unlike a star as anyone could imagine. On a recent visit to her home this writer found the children very well adjusted to each other. They seemed at ease with both parents and are all treated equally.

On one occasion, when Liza interrupted a conversation to ask her mother a question, Judy very quietly told her we were talking and would she mind waiting a minute.

A moment later, we finished our conversation. Judy turned to Liza, saying, “Now, darling, what was it you wanted to say to me?”

Then baby Joseph toddled into the room in his pajamas. He clambered up on Judy’s knee while we talked. When it was time for his supper Judy smothered him with kisses and said, “You’re the nicest baby in the world and I love you.”

Obviously, Judy has no intention of neglecting her children as she was neglected as a child.

During the week Judy was rehearsing twelve hours a day for her night-club act, recording an album for Capitol records and staying up all night with Joseph, who had a temperature of 104.5° for two days. In the evening she prepared dinner for the family while the nurse rested.

But you can’t explain all this to an audience which pays to see a performance, and Judy knows it. Bleary-eyed and tired, she went on in Las Vegas; and the few shows she missed were probably the result of genuine fatigue.

But on opening night she was surrounded by her entire family, brought in by train for the event. And she seemed happy.

“In the old days I was overworked and exhausted and had no idea of what I was punishing myself for,” she said. “I had no place to go and nothing that mattered and no goal.

“Now, when I get through work I’m still exhausted, but I go home at night to my family and forget about everything else. I have a full personal life besides a full professional life. One balances the other.”

In addition, Judy seems to have a good marriage with Sid Luft, despite occasional quarrels which apparently serve to clear the air between them. However, the cracks in Judy’s personality are still there, only temporarily mended. As long as she stays in show business she can expect to be on the receiving end of the strong blows which forced her out in the past.

Recently, Judy returned to the Palace Theater in New York where, again, she emerged as Queen. The superlatives lavished on her were necessary to keep her going. In one of her rare moments of self-analysis she told a friend what it meant to her to be a success, why it was necessary.

“When people go on telling you for years that you are washed up, finished, you begin to think maybe they’re right,” Judy told her friend. “Then you sit down and think that if you once had talent, maybe you still have it.

“So you work, work, work to polish it up again and you try and go on trying. Finally you are as ready as you can be to go before the public again.

“On opening night you are sure you are crazy. You suffer and you writhe. You know you are not going to be able to sing a note. You know nobody is going to like you. all those tales about you being no good keep going through your head and you wonder why you ever got into this again.

“The curtain goes up and you totter onstage, half-stupefied with nerves. You barely know what you are doing. It isn’t until that first applause comes crashing up that you get any relief. They go on clapping and you are so happy you want to cry and hug everyone down there. You’re not finished. You’re still Judy Garland—and they still like you. And you think, like a prayer, God bless all of you, for understanding.’ ”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1957

AUDIO BOOK