You Can Help Doris Day Get Well!

“Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.” William Shakespeare said it, and a thousand Hollywood stars— stars who have gloried and trembled, triumphed and wavered—have known this deep uneasiness. In those hours between midnight and dawn when inky blackness gives way to grey, cold light, many a troubled star has watched the approach of another day with weary eyes.

Doris Day—fun-loving, vibrant, radiant—finds today that the crown which she has worn so admirably for nearly five years is growing heavy on her head. And in those hours when the mantle of gayety no longer warms her, when she must dare to face herself alone, accompanied only by her own fears, hopes, desires, are there tears instead of laughter?

The buoyant Doris is disturbingly subdued. When the shooting of her current film, ironically titled “Lucky Me,” was postponed again and again, her family and friends wondered—and worried. And Doris, normally the most communicative of people, would say nothing about what was troubling her. Whatever her problem, she was keeping it to herself, brooding over her own dark thoughts.

What exactly has happened to her?

This, only Doris herself—and perhaps her husband. Marty Melcher—can say. But the known facts can, in part, speak for themselves:

A short time after the completion of “Calamity Jane.” Doris went into seclusion. To all appearances, she was merely “between pictures.” But the starting date for “Lucky Me” came and went. Again and again, it was pushed back on the calendar.

Finally, it was announced that Doris had undergone surgery for the removal of a small, benign cyst. Veiled rumors, however, insisted that her illness was far more complicated than this. Doris, for probably the first time in her movie career, could not be reached for comment. And her studio released only the information that their singing star would rest a few weeks—on the advice of her physician—before beginning the film.

But the rumors went on—nagging, insistent. One columnist reported that Doris was in a state of collapse and that it was doubtful that she would resume work before the end of the year. Another said that she was under the care of a psychiatrist.

Finally Marty Melcher broke the tense silence. “The report that Doris Day is in a state of collapse is not true,” he said. “It never was true. The history of Doris proves it isn’t true. It was a simple illness from which she has recovered. She’s up and will begin work in about ten days.” And the psychiatrist? “There isn’t any!” Marty stated emphatically.

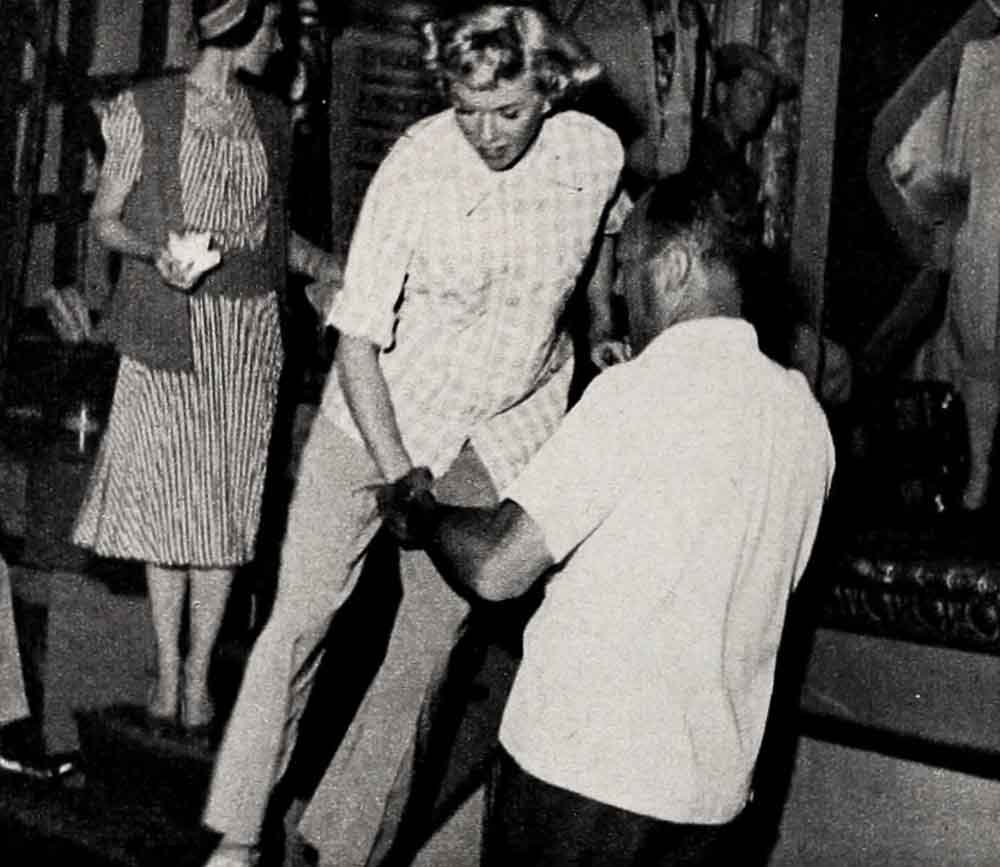

And Doris Day did return to work—but not the Doris Hollywood had known. Her sets, in the past, had been alive with her own special kind of radiance. They had bustled with activity—Doris being interviewed between scenes, posing happily for pictures, welcoming guests.

Now the door to the “Lucky Me” sound stage spelled out a forbidding message in large red letters: no visitors. And Doris herself has been wan, sometimes tearful, almost always solitary.

The fantastic arsenal of energy upon which she has drawn over the hectic years of her career may have begun to be diminished. For Doris has always worked and played and lived hard—with all of herself. But this is unlikely. Such natural vitality as hers is not easily snuffed out.

It’s much more probable that when she underwent surgery (frightening enough in itself), she had something she had not known for years—time to think, to review her life, to evaluate. She had time to ask herself how long her happiness could last. Time to look back on the days of her early struggles, her youthful heartbreaks—and perhaps to tremble a bit in retrospect.

Since her marriage to Marty Melcher, Doris has known real peace of mind and emotional security. Not long before her illness she said, “Today, I’m just about the most fortunate and happy person alive. I’ve treasures that are beyond all price . . . my son, my husband, my mother, my work.” And then she added, “But there have been times in my life when I didn’t see how I could go on any longer—when I felt I’d never really laugh again.”

Have those times come back to haunt her now?

Doris’ very success today is the result of a tragic accident when she was fifteen which broke both her legs and ended her dreams of dancing. It was only then, when her career plans were brutally blasted, that Doris discovered she could sing. And during the fourteen months she was confined to her bed, she planned a new life.

Discouraged? She never let on to the world. Still on crutches, the courageous youngster found employment in Cincinnati radio stations. Soon she was headed for the Big Time. She was singing with Les Brown’s orchestra when she met and married Al Jordan.

Doris promptly gave up her job and settled down as a housewife in Cincinnati. But something went sour and even Terry’s arrival couldn’t hold the marriage together. Doris and Al were divorced in 1943. Terry went to live with his grandmother and his mother began her painful struggle for stardom. She had to make good, for success meant security for her son. She sang at night, slept by day, lived out of suitcases. Tired? It mustn’t show on the bandstand. Worried? Don’t let anyone know.

When she wed musician George Weidler, Doris once again gave up all thoughts of her career. She kept house in hotel rooms and, during the housing shortage in Los Angeles, made a home in a trailer on a dusty vacant lot. This marriage was for keeps, she’d vowed, but the odds were against it. Doris and George separated and she went back to work. Work was always a good remedy for heartbreak, wasn’t it? Her audiences loved her gaiety as she sang. But inside she was crying and, every so often, she sang with tears streaming down her cheeks.

The day Doris’ agent took her to Warner Brothers to see director Michael Curtiz was a bleak one. This was the opportunity of her lifetime, but somehow she couldn’t manage a smile. The decision to make the separation from her husband permanent was fresh and she had cried all the night before. When she started to sing “Embraceable You,” the song reminded her of George and she began to cry again.

A wise man, Curtiz saw through the tears. He saw warmth and feeling and understanding—all of the qualities that belong to the industry’s greatest stars. He talked to her as a father might. “I needed that so,” a grateful Doris said later.

With her first film, “Romance on the High Seas,” Doris found success. At last, she was able to send for Terry and her mother and give them a real home. But could she ever be sure of lasting happiness and security? Of the personal serenity she needed so? Each time she had thought she had them within her grasp, they had vanished cruelly.

And then she found Marty Melcher.

Now, in this period of wavering, you hear the phrase again and again: “Thank heavens she has a wonderful guy like Marty to see her through.”

With the happy burgeoning of both her career and her marriage, Doris discarded the somber cloak she’d worn so long. The change was not gradual. It was sudden—if anything, too sudden. Doris determinedly remade her life. She seemed to become immune to such emotions as anger and fear. Apparently nothing could hurt her. Doris Day was the happiest girl in the world. One writer, who paid several visits to her sets, was amazed. “The director would yell ‘Cut’ and everyone would pull off to the side to rest. But not Doris. She kept going—joking, rehearsing, singing. Other people could blow their tops right and left. But nothing seemed to annoy this girl,” he said with astonishment.

Photographers could always count on her for happy photographs. Magazines could count on her for happy stories. And the public could see her films and go away whistling.

Doris’ new-found philosophy was not devised entirely for her own benefit. “When I first got into movies, my job represented security. It meant that I could take care of my son and my mother and myself,” she said. “Now I see it is my duty to entertain people. That’s my place in life . . . and if I can bring a little joy to all kinds of people, my mission is complete.”

But can such natural feelings as irritation and anger be entirely ignored? Never allowed to come to the surface? Is it possible suddenly to cast off all unhappy memories? Or are they likely to be revived again through something no more serious than, perhaps, a pinprick of unpleasant gossip? Like the completely false but widely circulated story that Doris was selling photos to her fans. This, to a star who, with her mother’s help, has conscientiously seen to it that every one of the 15,000 letters she receives each month is handled personally, can carry a sting of cruelty far out of proportion to its importance. Particularly at a moment when, physically, she is not at her peak.

“Some people take keen delight in knocking down reputations,” said Marty when the story reached his ears. But what malicious intent there was in the tale may have reached its mark more surely than its unknown instigator dreamed.

“Doris is a normal girl,” Marty put it at the time. “She doesn’t claim to be anyone supreme. She has faults. So does everybody.”

This perhaps is the key to the Doris Day illness. She is normal. She is human. It’s possible that the very same people who unwittingly helped build the legend of Doris Day have just as unwittingly begun to tear it down. It is a legend that, for Doris’ own good, should never have been created . . . for living it twenty-four hours a day could easily have proved too much, even for a Superwoman. And Doris is human—flesh and heart.

As she said of Michael Curtiz’s kindness and understanding during those other bleak days, encouragement means so much to her. Now she needs it more than ever— from you, to whom she’s given so much. You can help still her fears. You can help Doris Day get well!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1954