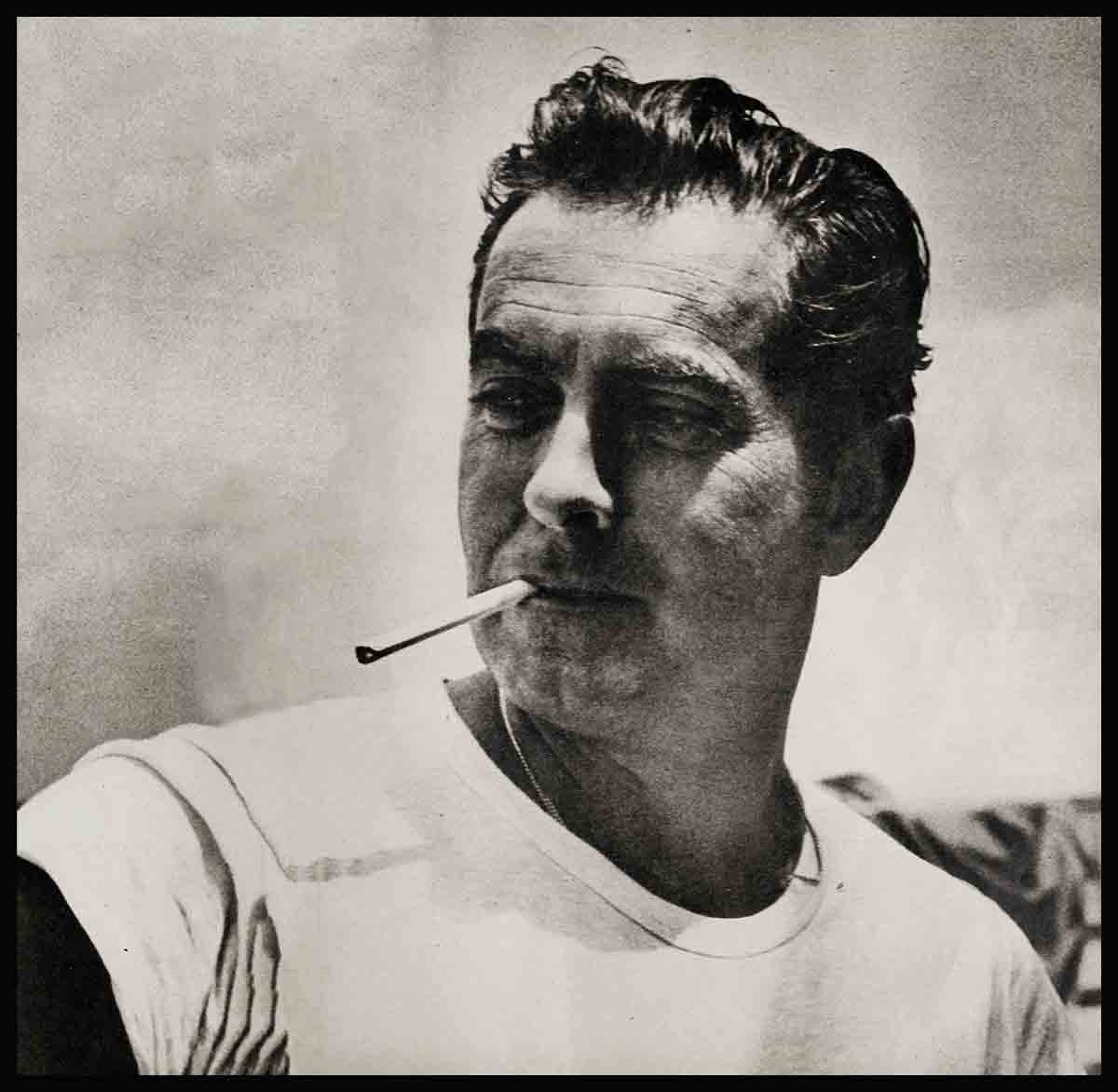

It’s Been A Good Life—Tyrone Power

When a film star decides to buck the stage, somebody always wants to know why in thunderation he does it and the star replies that it is a challenge. It is an innocent colloquy, predicated on the knowledge of both that the star is at least temporarily washed up in pictures and is needful of maintaining his wardrobe, his alimony, and his three meals a day.

In the case of Tyrone Power, there occurred a mildly interesting switch. Power, who is not washed up in any sense, still did not bother to reach for the “challenge” handle. He said “security.”

“Work,” he said, sweating frankly in 106 degrees of Lone Pine, California, heat, “is the actor’s only provision for security. It’s his back door, the old escape hatch. That goes for the rich ones, too, and how many of themdo you know? I know some. Got enough money in the bank to last them till they die. Last ’em real fancy, too. But they haven’t got security. They’re stagnant. You know who I mean? Wealthy, idle, miserable in the knowledge of their own limitations, actually very unhappy people. I don’t care how well-upholstered a vacuum is, it’s a vacuum. Nature hates its guts, as somebody has said before me. And better. You go forward, you go backward, or you die. And if you’re going backward, you might as well send the mortician a memo anyway. Just so he can begin scratching around, getting things ready. But the squirrel cage is worst of all.”

Lone Pine had promoted another half-degree of heat while he was talking. This was August and Lone Pine was really leaning into it. The scene was location for 20th Century-Fox’s King Of The Khyber Rifles, the fourth week the company had been at it, and everybody looked a trifle wilted. Power and his leading woman, Terry Moore, were having a rough time of it in a dismantled fortress looking out on what was presumably India’s Khyber Pass. Although Power and Miss Moore had spent most of the day in the fortress, they now were just getting ready to reach it, a piece of directorial sequence too complicated to go into. They had to grope in out of a dust storm, and not even Darryl Zanuck can will a dust storm in the Mojave Desert. Explosive had to be detonated and wind machines set to work. Visitors to the set were being urged to step aside a trifle—say about a mile down the road. “Please, please!” said an assistant to Director Henry King. “Anybody not connected with this sequence, please! Take to the hills!” The wind machines snarled into action and Miss Moore, who is not fond of noise of any kind, squeaked and cowered.

She and Power, among others, were seated on canvas chairs banked forward on a slope of earth, directly behind the cameras. Power wore boots, rather snazzy campaign breeches and a T-shirt, having divested himself of tunic and kepi shortly before. Miss Moore, on the other hand, was dressed to kill—any male, for example, who happened to be lurking around Khyber Pass in the middle of the nineteenth century. What she was doing in a besieged fortress thus togged out was anybody’s guess, with the script writer the probable winner.

“I’m not just generalizing,” resumed Power, over the noise of the machines. “I’d be a fool not to know this thing’s going to blow up. My association with pictures, I mean. I’m pushing forty. The younger men are pushing up behind me. The kids are pushing up behind them. But the trouble with that figure of speech is, they’re not boosting me, they’re dislodging my handhold, and sooner or later, there’s not going to be room for everybody. All right. Last come, first served. That’s how I got there, too. But now’s the time to get the net ready, the one that has to break the fall. Not later. And there you have John Brown’s Body.”

Paul Gregory’s production of John Brown’s Body, as just about everybody knows by now, is the dramatic reading of Stephen Vincent Benet’s poem, in which Power, Raymond Massey and Judith Anderson have been touring the country. It is significant that of the original group, only Power was reasonably firm in pictures. “When,” he said, “you’re through in this business, you’ve got to have established that you can do something else.”

As he spoke, Power’s professional standing, as closely as can be determined, was approximately this:

When he first went out with John Brown, he was slipping. He. was, for instance, no longer the apple of Fox’s eye, no longer tendered their gaudiest parts as a matter of course, and there had even been talk of a loanout to a lesser studio, worthy picture makers but sometimes an oasis on the escalator down. Instead, the loanout was to Universal-International and a film titled Mississippi Gambler, made in five fast weeks but mother lode as far as boxoffice was concerned. Since there was no discernible reason for this, save Power’s presence in the cast, he found himself promptly back on top of the chute again and tossed by his home studio into Khyber Rifles, big budget stuff for these days. Yet the resurgence appears neither to-have excited him nor settled his qualms. His verbal animation he reserved for his upcoming John Brown reprise and his problem as a whole. Indeed, the process of Khyber Rifles seemed to affect him as no more than a chore he had done before, likely would do again, and where was a good place to eat that night?

“Forty,” he repeated, as though the idea both fascinated and oppressed him. “Forty years old. Not quite but almost. There’s no such thing as forever. That loanout was the first I’d had since I’ve been with Fox. Seventeen years with one studio, take or give a dime. That’s all right in a way. In another way—well, it’s the old squirrel cage again. This kind of picture here—” he indicated all of the Khyber set with a wave of his hand, “I guess it’s fine for the studio. I’ve made enough of them. Dashing fellow under the kepi, and all that. Stand the varmints off and tell the little lady to keep her head down. But the edge wears away and wears away until one fine day you’re looking down a one-way street and no room to turn around. That’s when you need an out.

“Mine, in a sense, came with the war.” Power served with honor as a Marine flier, first lieutenant when he returned to peace time. “A man would be a dangerous lunatic to speak of war as a blessing in any way, shape or manner, but I did come back to pictures with an entirely new perspective. That lasted two, three years. Then I could feel the staleness setting in again, the edge going. You know? Over and over. Swash and buckle, damn the torpedoes. One picture I liked. Nobody else seemed to. Nightmare Alley.” Nightmare Alley, re-capsuled here simply to illustrate the divergence between Power’s point of view and his employers’, was derived from a book that featured the degeneration of a carnival performer to the role of what carnies call a “geek.” A geek does not rescue distressed females. He bites the heads off living chickens in a sideshow. Power later named a plane in which he toured the world The Geek. “I thought that picture would do something for me,” Power said. “My mistake.”

“Here’s where I earn my money,” said Power. “Don’t go away.” He and Miss Moore walked out into the desert about fifty yards, turned and oriented themselves toward the fortress setup. They joined hands. The spectators were clear. There was a deep, coughing blast, three converging wind machines boiled into high, and dust writhed and billowed up in an impenetrable cloud. A few onlookers were genuinely scared. Presently Power and Miss Moore appeared out of the holocaust. They were the dustiest people you ever saw, their eyes staring out in pale, dark-ringed surmise. It developed they couldn’t see a thing in there.

“All I could think of,” said. Miss Moore, “was, what if we walked into a wind machine?”

“A hell of a thing to happen to a man up in Khyber,” said Power.

There was excitement and confusion up forward. Power grunted and turned sidewise with his hands up. “A hair on the lens,” he translated obligingly. “Got to do it again.” A hair on a camera lens makes for a picture that is divided and tricky indeed. “Well, what’s the difference? You know what they’ll say anyway, when the picture’s released. ‘Doubles. They always use doubles for shots like these.’ That’s what they’ll say.”

Power does not, as you know, look forty. He looks, as you know equally well, like an amalgam of all the gentlemen in the toothpaste ads with the redeeming qualities of animation, humor, and high, articulate intelligence. He no longer has the juvenile façade of the pre-war years—his features are set now—but there are few lines, few departures from symmetry. He could still bound onto a musical comedy stage in flannels, carol “Tennis, anyone?” and get away with it, were he so a-mind. He is not so a-mind.

“After every picture,” he said now, while functionaries were chipping off the lampblack; “I’d go to the front office and ask for another formula, a change of pace. It was like talking down a rainspout. I don’t have to tell you. They knew best. Well, they did know best—for them. And for me, too, looking at it in a different way. You know, I sit here barking like a seal with colic, but this is strictly shop. I mean, you take the broad view and I owe pictures everything I’ve had in life, or adult life, and that’s been plenty. And by pictures, I’ve got to mean Fox. Besides all the other stuff, money and whatever the polite word for fame is—public interest, I guess—I’ve been all over the world, met kings and presidents—there’s just been no limit to it. I’ve got to say that. Every star’s got to say it if he’s not the world’s bottom slob of an ingrate. But the mistake is to ride with it, sit back and figure you’ve got it taped once and for all, I’ve made it, this is the end, I’m up to my rump in the pot at the end of the rainbow, amen. Accept that and it’s the beginning of the end. You haven’t arrived. You’re dead.”

He stretched out his dusty boots, leaned his head back and closed his eyes, bloodshot from dust and sun and ready for the little man with the drops. “Take Hollywood,” he said. “I mean, the industry, the climate of Southern California, the whole set-up. It’s not really a good place to work. And it’s a worse place not to work, to lay off between pictures. Hollywood’s a lotus land. The sky is blue, the air is soft, the swimming pools are the right temperature, flowers everywhere, even the outdoor furniture is comfortable. Oh, you could lie back between jobs and vegetate in those lush surroundings, and God help you! What you ought to do—what I ought to do, what I have to do and do do—is get out right after a film and stay out till the next one. Complacency is too easy down there. They say death comes like a lover sometimes, and when I breathe night-blooming jasmine, I believe it. No, lotus land is no good for work. The thing now is, make two pictures a year—you can’t make more anyway—and when fall comes, go out on the road and work at your trade. Keep at it. Stay alive, or that monkey with the jasmine breath will get you yet.”

Lone pine proper, 1000-odd population, twenty-seven miles distant, drowsed heavily in the late afternoon sun. It would have drowsed in the shadow of Mt. Whitney, the United States’ biggest, if Mt. Whitney had been casting a shadow that day, which, oddly enough, it was not. Lone Pine isa village long inured to movie locations. In a combination restaurant and bar, a waitress said to another: “You seen Tyrone Power yet?” giving it a pretty big Ty. Power thinks of his first name as Tuh-rone. “Unh-uh,” said the other. “One I want to see some time is this Robert Wagner.” Both girls are under twenty. At the bar, a derelict of sensational aspect was in the custody of local law, who had orders to have him on the next bus out of town. “I threw a guy through a plate glass window last night,” he said tiredly. “I wish I wouldn’t ever again throw a guy through a window. They run me out of ’Frisco for the same thing.”

In the evening, it was cooler, down to about a flat ninety-five. Power, in his room in a motel south of town, was crisp and shaved and dapper in grey slacks and sports shirt, ready to take local friends of his to a farewell dinner in a nearby cafe. The friends had a filling station out the road.

“When you’re a so-called rising star,” he said, “which I was back around the time Alcock and Brown flew the Atlantic, or so it seems right now, the psychological outlook is entirely different. You live from one picture to the next, there’s no tomorrow, and you never had it so good. Then one day you’re what they call an established star. Don’t ask me when or how that day comes about because I don’t know. But that’s when you’re supposed to have it made, really made. Naturally, that’s not the case. That’s the day you begin building for the future. That’s the day you remember that sooner or later you start down the other side. You asked me about the difference in psychology, that’s the best I can do for you. Come to think of it, its good enough, at that.” He changed the subject.

“You know, these four weeks up here have really been something. Work, eat, sleep, read, go to the movies if you feel very footloose. Nothing else. It’s wonderful, except that I ought to be home.”

Linda Christian Power was, roughly two weeks thence, expected to present her husband with the Powers’ second child, confident it would be a boy. The prospect momentarily derailed Power’s train of thought.

“Linda is truly the one to ask,” he said. “The mother’s so much closer to these things. For my part, any child of mine, boy or girl, would have free rein until he reached the age of reason. What’s that—seventeen? Then I’d want to steer them as best I could, then implement for all I’m worth the decision they reach. Doctor, lawyer, merchant, nurse—or actor. I haven’t any fixed ideas right now, but then our first child, Romina, is only two, you know. There’s time. By the time she does reach that age, I’ll be close to fifty-five and ought to have made up my mind in some way. One thing, if either or both do decide that acting’s the deal, then I think we can dispense with some of the formal education. It’s not necessary to an actor, and I think I speak with some authority. A different sort of schooling and environment would be better. That’s pretty sweeping speculation, though. They’ll make up their own minds.”

Power, of course, is as much the product of theatrical forebears as the Barrymores are. His great grandfather started it all on the Dublin stage in 1827. That was Tyrone Power, the original. A grandfather declined this particular tag, but Power’s own father, a noted Shakespearean actor earlier in the century, was Tyrone Power II.

Tyrone Power may be ready to say goodbye to Hollywood now, or au revoir at the least. It is fairly well established that he wants to set up his own producing company in Rome and that plans are, at this time, well along toward completion. When he’s not doing that, he’ll be play-acting where-ever audiences can be found. The circle that, for him, began in earnest in 1936 with the Fox picture, Lloyds Of London, has come complete now. The dossier above is offered in evidence.

But it was quite a circle for all of that, and considerably slow in beginning. The first breath took place in Cincinnati, where testimony indicates he was a well-behaved if not prodigious infant. After that, there was a spell of being trunked about from one theatre habitat to another, and a sitting out of World War I on the sands of Coronado, California, while his mother supervised troop entertainment in and about San Diego. Power was roughly thirteen years too young for the draft.

The legitimate theatre took rather kindly to Power as a child mime, although veteran player Fritz Lieber almost tore his head off with a knife—purely by accident—during a rendering of The Merchant Of Venice. By and by, he was ready to foresake this and sniff around the edges of the Hollywood cheese. But the time was not yet.

Furthermore, his associations’ with- the place had “been jarred shockingly by the death of his distinguished father. While working on the film, The Miracle Man, he collapsed, and, hours later, he died in his son’s arms.

There was stage and radio work further east for a longish spell after that, usually under expert tutelage. Don Ameche helped, Eugenie Leontovich helped, Helen Mencken helped. Katharine Cornell helped. You can’t get much better help than that.

Followed then summer stock, followed then more Broadway (notably the role of De Ponlengey in Miss Cornell’s St. Joan), followed then Darryl Zanuck.

Nor is it, nor has it ever been, at that time or later, fair to say of Power that his prime asset was a supremely photogenic face with an overlay of animal magnetism. Spectacular refutation, at any rate, of this quasi-slur is contained in the observation of Edmund Goulding, a stage and film director of sound critical faculty, who has referred to Power categorically as “the greatest actor of this generation.” The effulgence of that one is thought by friends sufficient to warm Power for a lifetime.

Once set in films, Power played his cards as they fell, but with the increasing restlessness of an authentically sensitive and creative talent. The timely—as ever—arrival of the United States Marines intervened. Sensitivity was. not precisely what they sought, but Power proved an asset, anyway. He moved up from boot camp at San Diego to ocs at Quantico, into Squadron 353 of the Marine Transport command, and flew out of such rest spots as Kwajalein, Saipan, Iwo Jima, Okinawa and Kyushu.

A new grip on things subsequently brought him in the post-war years to his greatest stature as a film actor, but, as duly recorded, the inroads of what he believed to be a static situation began to gnaw at him again. The hair in his personal lens diffused the frame into several Tyrone Powers: star, world traveler, international gadabout in a quiet way, some disposition to a scholarly bent to which he has always been more or less subject, and finally the flowering of his professional growth in John Brown’s Body. Here was a cleavage, an incisive turning away from one thing and toward another.

Power’s official Fox biography, a rip-roaring document of eleven pages, states among other musings that its subject’s favorite color is blue, his favorite fruit the avocado, his favorite classical painter Van Gogh, and his favorite illustrator Petty, he who throws perspective away when it comes to girls’ legs. Assuredly, the biography is thorough. Its one mainfest failing is that it comes to an end. There is a strong feeling here and there that this is not the ease at all, that there is a great deal more to come, and that the second part will be better yet. The hair in the lens may have moved aside now; the picture should be clearer.

THE END

—BY JOHN MAYNARD

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1953