1957 A Crazy, Wonderful, Mixed-Up Year

As they would phrase it in the best Hollywood drawing rooms, anyone for a crazy, wonderful, mixed-up year?

How else would you describe 1957—the year the Jayne Mansfields boomed the bust, the Audrey Hepburns busted the boom and success really didn’t spoil anybody. But some of the over-sized egos did.

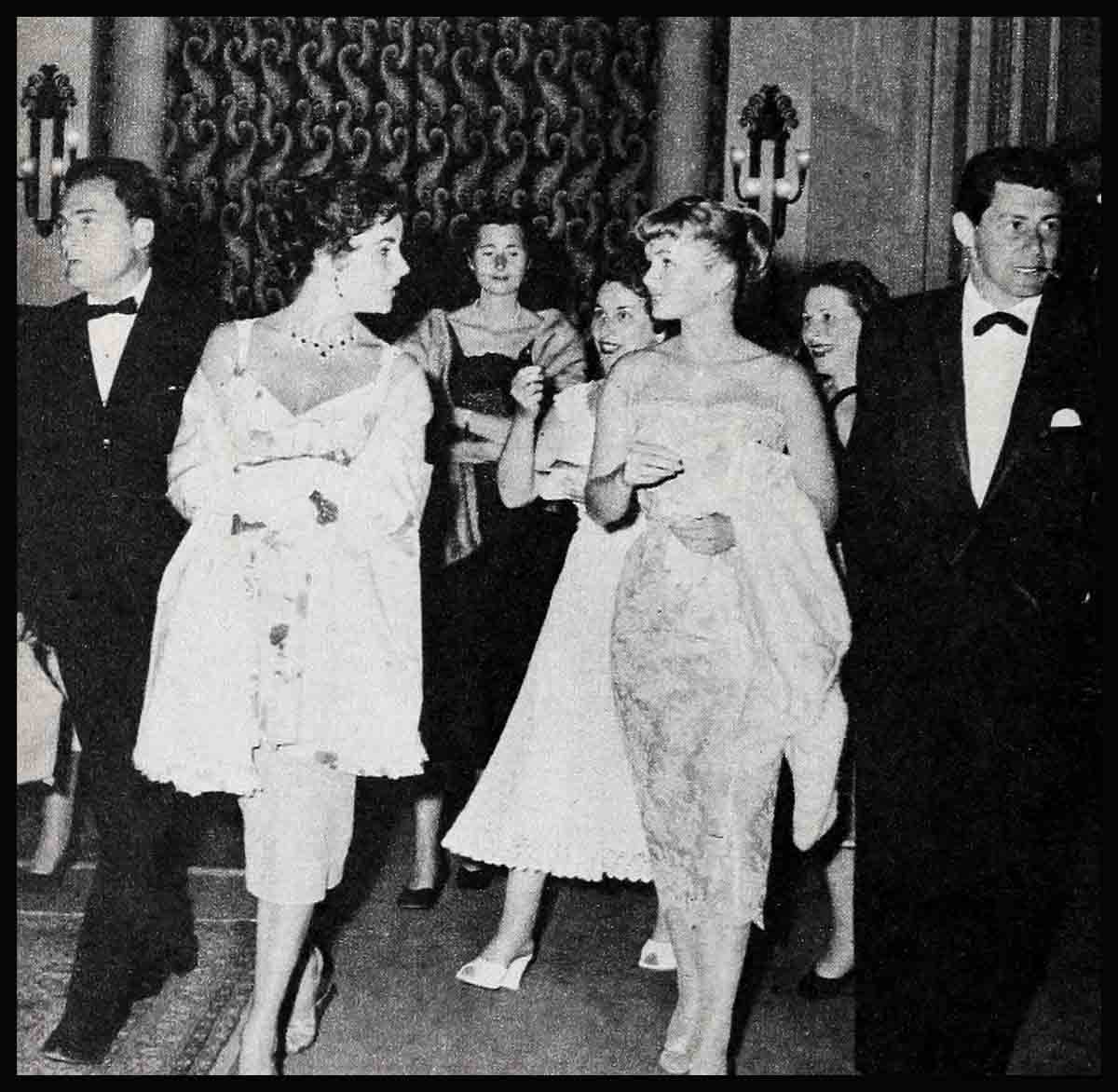

It was the year Mike Todd took up permanent residence on the front pages, became a household word, staged airport scenes with Liz, put Elsa Maxwell to shame and became a proud Pappa to boot.

’Fifty-seven will go down as the year actors turned to singing, singers turned to acting and Elvis just stood there and wiggled. It was the season everybody wore bulky Italian knit sweaters, drove sleek Italian cars and went mad for Scandinavian furniture.

Hollywood’s hep set clapped to calypso, argued over rock ’n’ roll, then tired of both. Country boys like Pat Boone and Tommy Sands wowed the city slickers. Pat made his first movie, his first half-million and first-rate grades at Columbia University. He was big news in ’57. He revived old songs, not only plugged the clean, family life but lived it, refused to smooch it up on the screen with his leading lady, and finally compromised with a near-kiss (a quarter-inch apart).

It was the year that Brando went blond (for “The Young Lions”), Tony Curtis hennaed (for “The Vikings”) and Pixie Shirley MacLaine continued to comb her hair with an egg-beater.

It was the year that Natalie Wood dated everyone from Elvis Presley to Frank Sinatra and ended up announcing she was in love with Bob Wagner. Wood and Wagner quickly became the Debbie and Eddie of ’57—the cutest courtin’ couple in town.

Natalie had a big year in more ways than romance. She snagged the prize role of “Marjorie Morningstar,” was signed to co-star with Frank Sinatra in “Kings Go Forth,” won a salary increase amounting to $50 a minute, and showed every sign of becoming one of the top stars in the business. Not bad for a nineteen-year-old.

Nick Adams managed to show up at every party—at least every party where photographers were present. This record was equaled only by Jayne Mansfield, who not only showed up, but nearly showed everything.

’Fifty-seven was the year that Frank Sinatra didn’t visit Australia, didn’t care for the midnight visit of a process server, insisted he didn’t help break down that “wrong door,” and didn’t comment on his love life, Lauren Bacall, Ava Gardner or pert Peggy Connolly. Yes, The Thin Man made the papers almost as regularly as the weather report. Every time he hit the ceiling, he hit the headlines.

And it was one of Frankie’s happiest years, personally and professionally. He patched up most of the feuds he’d been carrying on with members of the press, had three successful pictures released—“The Pride and the Passion,” “The Joker is Wild,” and “Pal Joey”—and in case he still had time on his hands, recorded a few albums, flew to Europe, tackled a series of TV shows and played the Copa and the Mocambo. The latter he played for free, to help out after the death of its owner, Charlie Morrison.

Personally, Frankie and Betty Bacall were seeing a lot of each other in late ’57, but insiders were betting they’d never see the preacher—at least together.

Nineteen fifty-seven was the year Mrs. Eddie Fisher had a hit record and Mr. Fisher didn’t—which led one wag to wonder if Debbie and Eddie would have a long-playing marriage.

Betsy Drake quit playing the hermit and made two pictures, displaying a nice pair of gams in one. Cary Grant quit smoking and gave Betsy and hypnotism all the credit. He told their pals that his wife had hypnotized him out of the cigarette habit, and meant it.

It was the year that the Actors Studio types weren’t quite so intense. Some of them even gave up mumbling. Others stopped looking down their noses at Hollywood and started looking up to its successful veterans.

Brooks Brothers sent the sweatshirts back to the locker room. Young actors took up the “Tea and Sympathy uniform”—neatly pressed polished cotton trousers, clean white shirts, worn without tie and open at the neck and white sneakers, un-smudged. Cashmere pullovers or alpaca cardigans were the order of the day. By year’s end nobody who was anybody owned a beat-up leather jacket or enthused about bongo drums.

The big fad with Hollywood’s younger set was the midnight coffee klatch—practiced with dramatic overtones, of course. Their favorite hangout was a unique little coffee house called “The Unicorn,” down the road apiece from Schwabs’ and Googies’ on the famed Sunset Strip.

By unique we mean the place was painted solid black, inside and out, and was lighted entirely by candles. Kids like Dennis Hopper, Nick Adams, Tony Perkins, Sal Mineo, Dolores Michaels and Rita Moreno spent many hours at The Unicorn, sipping java in the flickering light and talking, talking, talking. What did they talk about? Mostly themselves.

’Fifty-seven was also the year for the “alone-in-a-crowd” look. Many of the young actors and actresses adopted it. As one of them explained, once you got the knack of it, it was a breeze. To look alone in a crowd one simply feigned indifference to everyone and everything. You were, of course, a poor listener. Girls heightened the effect by wearing pale pink lipstick and lots of dark eye makeup. This was supposed to make them appear attractively forlorn.

It was a crazy year, all right. There was Elvis his fantastic paychecks and his equally fantastic manager, Tom Parker. That’s Colonel Tom Parker, suh! Between the two of them, they managed to startle startle-proof Hollywood.

The Colonel drove a hard bargain and Presley drove a fast Caddy. The Colonel barked orders to studio bosses and Elvis politely addressed everyone on the set as Sir and Ma’am. A member in fine standing of the Cad-a-month Club, he fetched Ma and Pa from Memphis to see Hollywood and fetched half of the females in Hollywood down to Memphis to see Ma and Pa. It was a dull week when Elvis wasn’t making the headlines with a brand-new girl. Natalie Wood started the parade in ’56. Others who went along for the publicity ride in ’57 included Yvonne Lime, Anne Neyland, and Venetia Stevenson.

It was, in fact, the year Venetia Stevenson dated more young bachelors, got her picture in more magazines, her name in more columns—but didn’t make any movies.

It was the year that oil was discovered in Hollywood and the derricks pumping away on the 20th Century-Fox lot were for real. Paramount, Columbia and RKO studios also were said to be on rich ground.

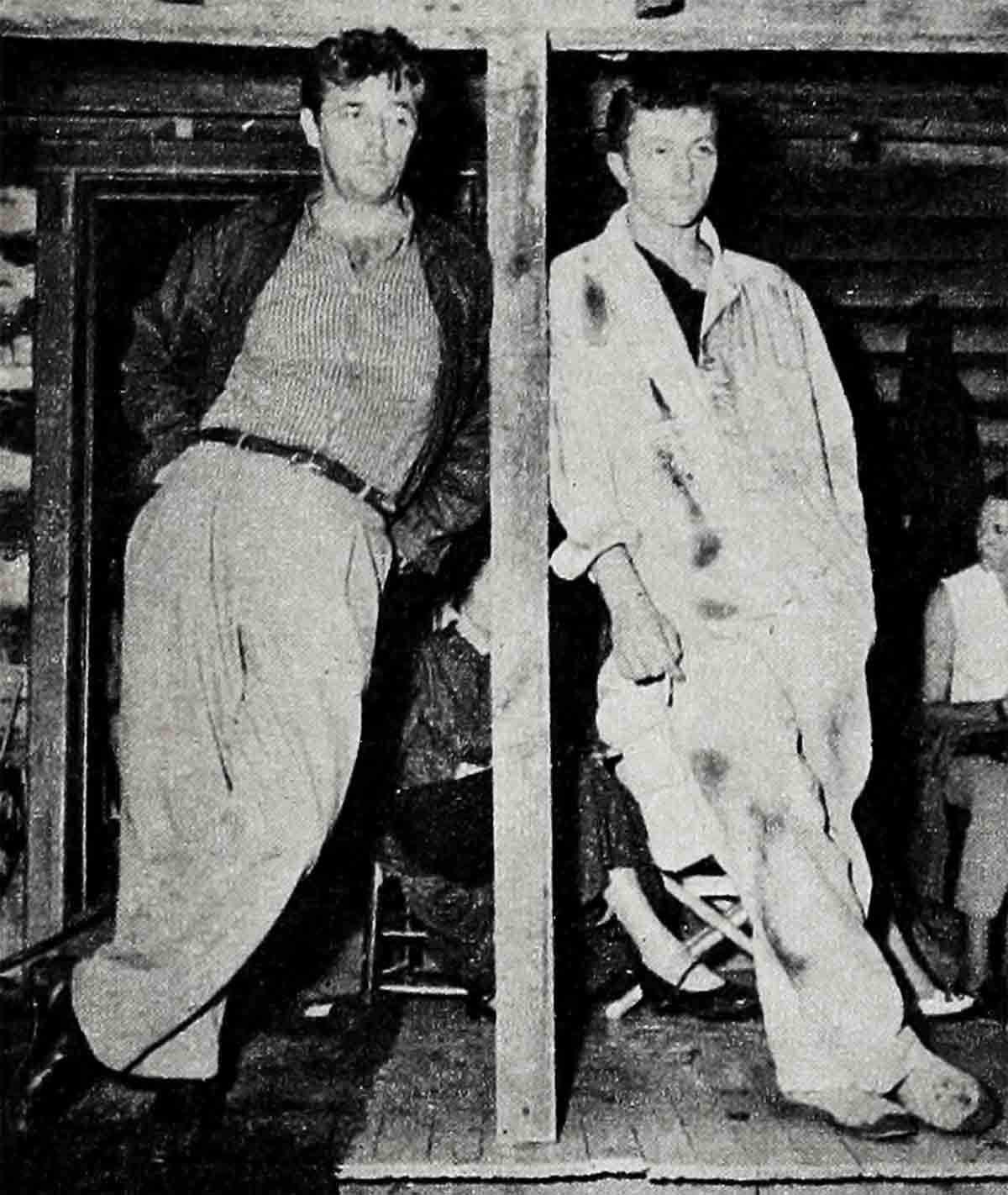

Jack Palance and Tony Franciosa made news by punching newsmen. Tony proved that his temper was as hot as his talent with the smashing performance he gave at a Los Angeles courthouse.

But on the more cheerful side, everyone in Hollywood praised Tony’s work in “Hatful of Rain.” There was no doubt that he was one of the year’s most exciting new stars.

Recording studios were the places to be. In ’Fifty-seven the young actors were spending as much time in them as they were on the sound stages. While singers like Crosby, Nat King Cole, Dean Martin, Julie London, Pat Boone, Keely Smith and Dorothy Collins were going dramatic, actors like Tony Perkins, Tab Hunter, Jeff Chandler, Bob Wagner and Sal Mineo were making platters. And hits at that.

Tab started the trend with his smash record, “Young Love.” DJs across the country just couldn’t spin it enough. Tony Perkins hit the turn-tables with his rendition of “On a Moonlight Swim.” One of the music critics observed that on wax young Mr. Perkins sounded more like Ma Perkins.

But Tony’s fans didn’t agree. In but a few short weeks the Perkins platter was out-selling the Presley platters, and the boys over at RCA were tickled pink.

Bob Wagner got into the act with “Honeysuckle Rose.” Sal Mineo recorded the title song from “Dino.” Speaking of title songs, 57 was a big year for them. There was Pat Boone’s “Bernardine,’ and Nat Cole’s “Raintree County,” of course, and Debbie’s “Tammy.”

Besides making records, Tony Perkins made three big pictures, moved to a bigger apartment, dated Maria Cooper and Venetia Stevenson and headed back to Broadway to open in “Look Homeward Angel.” He also bought a car, put his shoes on and quit hitch-hiking around Hollywood. No doubt about it, Perkins packed a lot into twelve months—including that exciting ingredient called success.

It was the year that Columbus’ descendants discovered Hollywood, and vice-versa. One of them a luscious lass named Loren, landed and proved that like the world, she was definitely round. In all the right places. And anyone who didn’t appreciate Sophia was definitely a square.

It was a great year for shapely Sophia. She handled herself well, made a big hit with everyone in Hollywood, wrapped up two pictures, “Desire ides the Elms,” and “House Boat” with Cary Grant and marriage by long distance.

Anna Magnani, another Italian actress, who didn’t give a hoot if she was a bit too round in the wrong places, also made things interesting for Hollywood in ’57. Anna’s talent, matched only by her temperament, proved that she hadn’t changed since her last visit here. She still didn’t bother with girdles, combs or gossip columnists—especially those who sought her opinion on the latest activities of her onetime love, Roberto Rossellini.

The magnetic Magnani promptly closed the set of “Wild is The Wind.” She ignored the press, got along fine with costars Tony Quinn and Tony Franciosa, but battled continually with producer Hal Wallis over the script.

When the final round was over, ringsiders agreed on one point—Magnani had turned in another championship performance on the screen. And everybody, including Anna had a laugh out of the quip that was making the rounds: “Did you hear about Magnani arriving on the set in disguise—her hair was combed!”

There were a lot of laughs in 757, And quite a few gasps. It’ll be remembered as the year Jayne Mansfield almost busted up Sophia Loren’s first Hollywood cocktail party. And we do mean busted. The photogs who recorded the historic meeting of these well-endowed young ladies are still shaking their lenses over the incident.

However, when Jaynie took off for Europe at the end of ’57 she announced she intended to change her style in ’58. Miss Mansfield threatened to be more dignified. She said she’ll raise her necklines and concentrate on her dramatic lines. Like another blonde named Marilyn, Jayne has now reached the I’m-going-to-be-a-great-actress stage.

Speaking of Miss Monroe, she managed to grab her share of news space in ’57. Marilyn lost the baby she and Arthur Miller wanted so badly. She also told her one-time chum, Milton Greene, to get lost. Milton didn’t care for the instructions and insisted that he still was a stockholder in Marilyn Monroe Productions.

In the hassle department, M-G-M got into a stockholders’ brawl that all but paralyzed the world’s biggest studio for months. David O. Selznick went to Italy to film “A Farewell to Arms” and lived up to his legend. He sacked so many people during the production that the gagsters retitled it “Farewell to David.” Director John Huston got the gate, and an umpteen-paged memo, because he allegedly didn’t see eye-to-eye with Selznick on the handling of Mrs. Selznick’s (Jennifer Jones) role in the film. Jennifer and Rock Hudson finished out their love scenes with another director.

Fifty-seven was the year that Crosby Kathy Grant, surprising almost everyone except the principals. Mrs. Jack Lemmon became Mrs. Cliff Robertson. Susan Hayward went to Georgia to find love and, to quote her, “the world’s best vegetable soup.” Attorney Eaton Chalkley was the man who won Susie’s hand.

It was a year of surprises. Bob Mitchum broke his ankle and said “Goodness gracious,” expectant Yvonne De Carlo put her leg through a glass door, Bette Davis fell down the stairs, Inger Stevens and Rod Steiger got stuck in a New York subway together, and Kim Novak’s Italian Count turned out not to be a real Count—just Italy’s Canned Tomato King. It was the year Liberace didn’t smile quite so much, or make quite so many trips to the bank.

Ingrid Bergman gave Rossellini back to the Indians—or rather, one of them almost captured him—and then took him back again. Cary Grant signed an autograph.

It was the year that Kim Novak fell out of love with Mac Krim, took up John Ireland, then dropped him and kept her Italian romeo on the string. It was a golden year fcr Kim, beginning with the Photoplay Gold Medal Award dinner. Her career soared with “Jeanne Eagels” and “Pal Joey.” She went on strike for more money and got it.

It was a big year for the big “biopic”—Hollywood’s short-cut word for the biographical picture. Real life stories filled reels of celluloid. And for a change they featured facts instead of white-washing with fiction.

If you didn’t catch at least one biopic in which the heroine loved the bottle or the hero was addicted to dope, couldn’t stop gambling or couldn’t find happiness, you just weren’t trying.

Type-casting went out the window in most of these films. Donald O’Connor wiped the bright grin off his face, donned a pork-pie hat and deadpanned his way through the not-so-comic life of deadpan comedian Buster Keaton.

Filmland eyebrows went way up at the announcement that teetotaler Ann Blyth, Hollywood’s original sweetness-and-light girl, had pulled an even bigger switch and snagged the lead in “The Helen Morgan Story,” as the colorful girl who sang the blues, loved the booze and was destined to lose. Ditto at the announcement that sweet Dorothy Malone would play not-so-sweet Diana Barrymore in “Too Much, Too Soon.”

Actress Blyth managed to guzzle her way through her script like a veteran. However, she didn’t have the drink and self-destruction department all to herself. Kim Novak, another real life teetotaler, tilted the gin bottle all the way through “Jeanne Eagels.” As Actress Eagels, Actress Novak was also shown dabbling with dope, damaging her career, suffering self-torment and finally dying backstage in a third-rate theater. Lots of laughs.

he huge ’57 crop of biopics also included the shocker, “Monkey on my Back,” the story of Barney Ross’ fight against dope. Frank Sinatra rolled the dice, bet the ponies, downed the Scotch and got cut up by mobsters as Joe E. Lewis in “The Joker is Wild.” Jimmy Cagney played Lon Chaney in “Man of a Thousand Faces,” and Bob Hope had some bad moments as Jimmy Walker in “Beau James.”

Warner Brothers spent $6,000,000 winging Jimmy Stewart across the Atlantic in what was not only the most expensive, but the most unusual biopic of ’57. The only thing wet in “The Spirit of St. Louis” was the ocean, and it had a truly happy ending.

Fifty-seven was the year Hollywood circled the globe. Authentic backgrounds and fresh scenery were considered almost as necessary to a picture as the stars. Never have so many traveled so far to film so much.

Hollywood movie companies were scattered from the Libyan desert to South Pacific lagoons. Cameras were grinding in Germany, the Italian Alps, the Italian seashore, the French countryside, the French Riviera, and the Norwegian Fjords.

The Near and Far East really got a workout, too. Of, course, not every producer made a picture in Japan. It just seemed that way.

In an attempt to beat the big tax bite, more and more of the high-priced stars went into business for themselves. Following the pattern first set by stars like John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, and Alan Ladd, they formed their own companies and produced their own pictures. At parties, frivolous chatter gave way to earnest conversation about production values and capital gains.

Marlon Brando, Lana Turner, and Kirk Douglas were among the new “producers.”

Marathon movies left their mark on 1957. The two-hour film became as common as the two-car garage. More important, the big, big pictures proved they had nothing to fear from the late, late shows. Fans left those little screens in their living rooms and eagerly flocked to the theaters to catch such great widescreen productions as “The Pride and The Passion” (two hours, twelve minutes), and “Raintree County” (three hours, seven minutes). “Sayonara,” with Marlon Brando, ran a mere two hours and seven minutes.

It was a good year for the popcorn business too. Longer movies meant more nibbling.

Possibly the biggest “big” movie to go before the cameras in ’57 was “South Pacific.” Twentieth Century-Fox spent over $5,000,000 to make sure that its picturization of the Rodgers and Hammerstein stage success would indeed add up to “Some Enchanted Evening.”

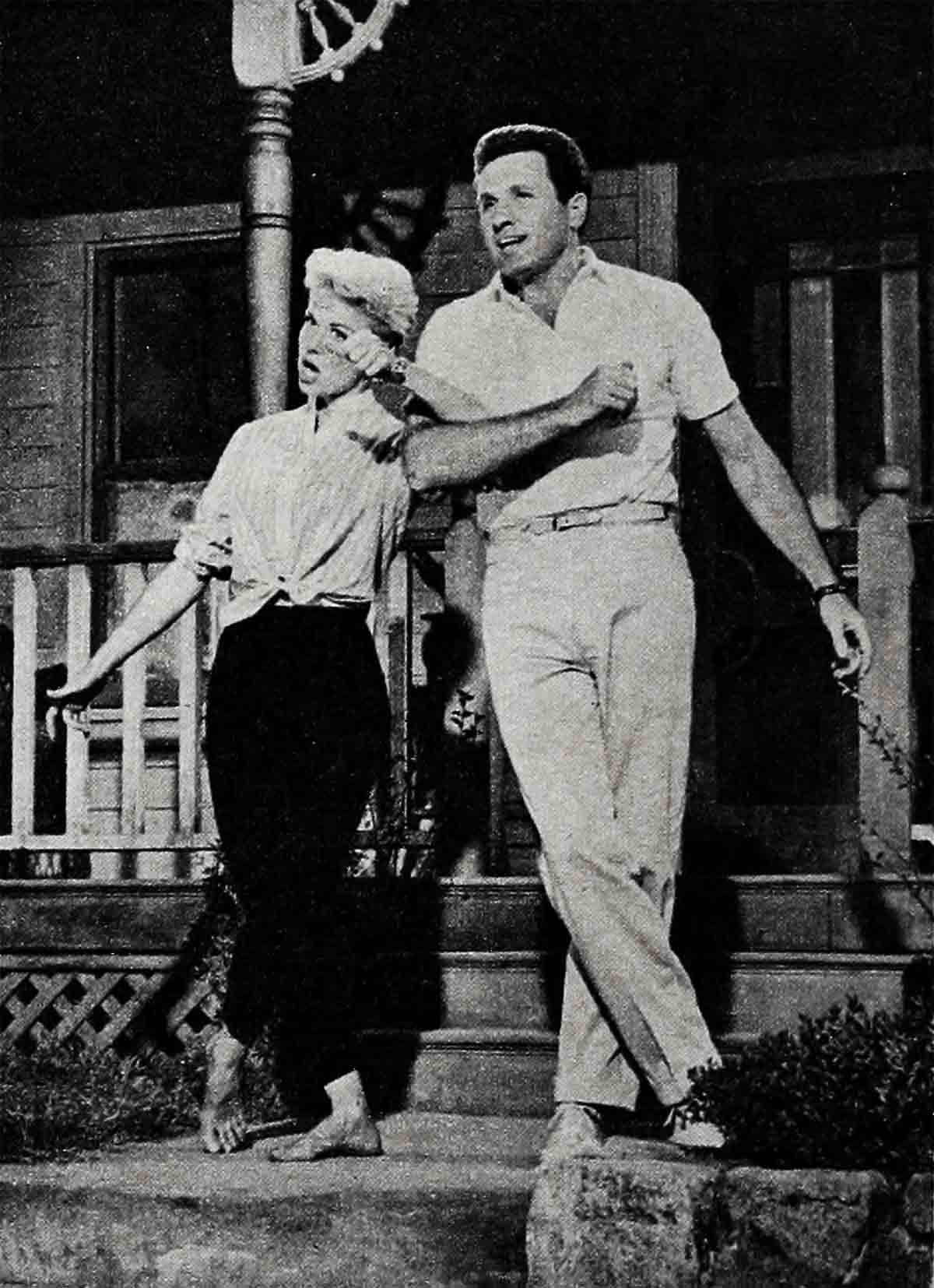

The picture’s expensive Hawaii location impressed even Hollywood. It called for the largest unit ever sent overseas by Fox. Acres of people, 120 to be exact, headed by Director Josh Logan and costars Rossano Brazzi and Mitzi Gaynor, worked two months on the island of Kauai.

“South Pacific” was certainly the biggest thing to happen to Mitzi Gaynor in 57, or any other year for that matter. And she was the first to admit it. Hard-working, ambitious and considerably more mature than when she first bounced across the screen a few years back, Mitzi was determined to turn in a great performance.

Hollywood knew surprise and happiness in ’57, when suddenly, out of the blue, Marlon Brando upped and married actress Anna Kashfi—rather Joanne O’Callaghan, filmdom wasn’t sure which. She looked Indian, claimed to be Indian, but headlines were screaming the exotic looking bride was actually studio-registered as Joanne O’Callaghan, daughter of a Welsh factory worker!

But Hollywood knew sadness this past year, too. Humphrey Bogart, the greatest and nicest tough guy of them all, died of cancer. In the months that preceded his death, Bogie proved what his close friends had always known—that he was also one of the bravest. And filmdom grieved the death of movie pioneer Louis B. Mayer, who contributed so much to the industry.

Fifty-seven was the year that Hollywood (and California’s Attorney General) fought back at the scandal. George Murphy, one the most respected men in the industry, took charge of plans to help protect Hollywood from the scandalmongers.

And ’57 was the year that Marie “The Body” McDonald starred in a real-life mystery that still has Los Angeles police detectives wondering. The blonde beauty not only got kidnapped, she misplaced her big diamond ring. The sparkler was uncovered, but just who put the snatch on Marie and why, has yet to be figured out.

But one thing is certain, the resulting publicity didn’t hurt Marie’s “comeback” any. Her new nightclub act was a big hit. Marie also wound up the year by reconciling with rich shoemaker Harry Karl for the umpteenth time. Harry was so happy about this he added another mink coat to Marie’s collection and tossed in a few more diamonds to boot.

The year saw the Motion Picture Producers Association revise its production code to allow more freedom in the treatment of certain subjects.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences made a much-welcomed announcement: In ’58 the industry is going to resume sponsorship of its big annual bank night, the Academy Awards presentations.

’Fifty-seven was a year for break-ups, make-ups and just status quo. Lana Turner tossed aside Husband No. 4, Lex Barker. Terry Moore and Eugene McGrath called it quits, then changed their minds. Ginger Rogers decided that one Frenchman could be wrong—she trotted into divorce court to shed Jacques Bergerac. Jeanne Crain and Paul Brinkman, who spent a lot of money on lawyers in ’56, and made some interesting headlines, decided to start ’57 out right. They reconciled New Year’s Eve. And near year’s end, newspapers screamed the separations of Rock and Phyllis Hudson and Jeff and Marjorie Chandler.

Jack Palance and his wife staged some preliminary fireworks in divorce court, then went back together again. Anita Ekberg and Anthony Steele battled in Brazil but patched things up in Copenhagen.

Yes, the year 1957 was quite the year—crazy, wonderful, mixed-up. And we wouldn’t have had it any other way.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1958

No Comments