Robert Mitchum Revealed: “Not As A Stranger”

For years Bob Mitchum has shrewdly kept the monster Mitchum, top box-office movie star, as far removed from Mitchum the man as possible. He has purposely permitted his publicized exploits to be used to add color to the already colorful complex character most people believe him to be. What’s more, he has made absolutely no attempt at his own defense. Yet behind the headlines is a man of brilliance, generosity, sensitivity, rebellion and great loneliness.

In the past year, the cardboard actor and the real man have started blending. There are good reasons. His friends, coworkers and enemies can tell you in part of the real man. Mitchum himself, inadvertently, helps give a first in the untold story of a misunderstood man. He fights like a trapped animal to his real personality from being seen, robed or written. This was a good night . . . there are wounds and bruises both sides to prove it. Let’s start with stories that would make him squirm embarrassment.

AUDIO BOOK

Not too long ago, on a publicity deal, Bob posed beside a 27“ television set Protocol calls for the star to receive a sample of the product. The Mitchums’ set went to a local orphanage and was placed in the sick ward. This sam e orphanage also has the pleasure of a fully outfitted electric train set. Jimmy and Chris, Mitch’s boys, lost interest after Christmas, so off it went to the kids who would love it.

Another time he sat in his dressing room at the studio with a batch of tickets to the Shrine Circus. He bought them for the kids at the orphanage. Suddenly he realized the kids couldn’t afford the accoutrements of a circus—popcorn, hot dogs, cotton candy and peanuts. He startled a lot of executives that day. Racing into their offices he’d demanded: “Give me five bucks—or two or ten,” The top man at the studio was nicked for twenty. To this day they may not know whether Mitch was suddenly going broke or they were donating to a worthy cause. At any rate, one hundred and thirty-five dollars backed up those circus tickets so the kids could go all the way. No one at the orphanage knew who sent the tickets or the money.

Is it beginning to sound like kids are a clue to Mitchum? While in Mexico City on location he was asked to appear at the local Boys Town charity. The studio gave him 500 pesos to donate. In fluent Spanish, he talked to the group, adding 1000 pesos of his own to the donation. In essence his speech w as, “I know what it is to be lonely and not loved as a child.”

That is the key to Mitchum the man. We know that childhood colors and shapes an entire life. Deep wells of memory in Bob Mitchum are the reasons for the wall he keeps so fiercely in place around himself—for his too-aggressive protection of the “little guy” (with whom he identifies himself), his deep love and devotion to his own children and to all children, his deep distrust for man in general and his aching loneliness. The complexities of Mitchum are very simple when viewed from the beginning.

His father w as killed in a railroad accident when Bob was eighteen months old. His mother went to work on a newspaper to support her three youngsters and a sensitive, brilliant, avidly curious child w as free to roam the streets of Bridgeport, Connecticut. At six he became bored with Bridgeport and began his long search for his own answers. He ran away from home. That time hunger brought him home. But from then, until the police grew tired of finding him and depositing him back on his own front porch, he persistently ran away, searching, sniffing and exploring life.

At twenty-one, Bob had been in almost all of the forty-eight states and he was beginning to find his answers. Sometimes he found the right answers the hard way and often the wrong answers the easy way, but they all planted some mighty implacable convictions in Mitch.

In hobo jungles, he found greatness—in places of authority he found dishonesty and cheapness. His contempt for authority took the form of resolute rebellion. His protection of the little guy gave him a kinship he had never known.

They became integral parts of his personality. From state to state and job to job he learned many kinds of hunger, some he could appease, others continued to gnaw. The hunger of loneliness drove him further into restless wanderlust. Casual nonchalance became the cloak to hide his Creative soul.

And under this nonchalance, his brilliance and sensitivity was growing through constant reading. Reading became an opiate. His retentive mind began storing bits and pieces and big hunks of knowledge away. His Creative talents began to stir and he started writing. He wrote night-club material for his sister, Julie, and radio Scripts. Quietly and for himself he started writing prose and poetry. There are two publishers with standing offers to publish his works when and if he says yes. But publishing his real writing would show the real Mitchum and he’s not ready for that yet. However, his intellectual and emotional fineness show when he doesn’t realize it. And his amazing memory and well-rounded education in reading quite often lets him go to bat with an authority on a subject and come out on top, which he loves.

His memory also shines when he gets a guitar in his hand and a small group of friends and lets loose with his rich baritone. He can sing old ballads for hours.

He feels music is the truest expression of man—perhaps because it does not have to articulate. He has a great record collection, from Bach to boogie, and it is used constantly when he’s home.

And home began with marrying Dorothy. Marriage was a wonderful step for Robert. For the first time he learned the emotional meaning of sharing himself with another, blending with someone else’s desires and wanting to put down roots— and being loved. Their first home was in Long Beach with seven other relatives in a two-bedroom house, then a tiny crackerbox, where their first child, Jimmy, was born and finally the lovely, comfortable place they now have. Fortunately, Dorothy is not a clinging vine. She has made their marriage a sharing one. They are comfortable together, laugh together and fight together. They both have a deep love for their children, Jimmy, 13, Chris, 11, and Petrine, now three years old.

It is with the children and Dorothy that the real Bob relaxes and enjoys, without his dukes up, the giving and receiving of love. He takes time with his children. He lets them know he loves them. He is proud of them.

If you were one of the few in the inner circle of Mitch’s friendship, you would have much to say about his beautiful speech, his deep soul and his inner perception. These few friends that he trusts, he permits to see him as he is. But they are probed completely before they enter. His hobby is people—individually, not generally. He is full of impractical compassion. He forgets important dates when he finds some distraught soul in need of talk or money. If it’s a little guy with a problem, there Mitch will be. Like the assistant director who was going to New Orleans to spot locations. New Orleans is one of the loves of Mitch’s life. He knows it intimately. So quietly, he long-distanced his friends there and asked them to give the assistant director the full v.i.p. treatment, resulting in the director having “one of the greatest experiences in my life.”

He is overly generous with all his possessions and money. When he received a gift of a $350 barbecue, complete with motor, it immediately went to a guy who had a small place in the valley who would love a lavish barbecue. A hard luck story has gotten the shirt off his back, the watch off his wrist or whatever he has in his pocket, be it five or five hundred dollars.

Dorothy finally insisted he have a business manager. Now he’s on an allowance and finds it difficult to be a one-man giveaway show. He also has finally realized that with taxes what they are, he must plan for the future of Dorothy and his children and is beginning to accept his responsibility without rebellion and with pride.

His friends are aware of his extreme needs in friendship. There are times when he is still the loneliest man in the world and is actually afraid to be alone. In these moods, he will talk all night with a “long on patience” friend until daylight eases his need. At the other extreme, he wants to be completely alone. Many times he has disappeared in the Florida swamp country for a month or two. The natives of the swamp accept him and he wanders restlessly, fulfilling some hunger. One time, Howard Hughes wanted him for a picture and finally had to send the State militia fifty miles into the swamp country to find him. Other times, he will disappear into the jungles of Mexico or strike out for the fishing country in the Northwest. These sudden revolts caused by “boredom,” he says, are strongly reminiscent of the wandering boy who kept searching outside himself for the answer to inner peace.

That wandering boy also found the instinctive sense of survival. Through the years he has turned that awareness into a diplomacy par excellence. For every time he has broken into print, there have been a hundred other times when he has extricated himself with great charm from a sensitive situation. Publicly considered a touchy guy, he is a natural target. One night while on location, he and Dorothy stopped in at a quiet little bar in a town near the set. A huge red-haired fellow took exception to Mitch. He moved down the bar and proclaimed his opinion of Mitch. Mitch suavely agreed that he was a first-class stinker. He and Dorothy moved to the other end of the bar. The man followed. He reiterated his opinion in stronger terms. Mitch agreed. He and Dorothy went to a table. The man followed and made a crack about Dorothy. He made one crack and he hit the floor. In spite of his protest, “I’d rather be an honest roughneck than a well-bred rogue,” Mitch is a gentleman through and through.

When Mitch and Jane Russell appeared at the unveiling of the Iwo Jima monument in Oceanside, they were asked to stay overnight and do a show at Camp Pendleton the next day to raise funds. They agreed, so Jane and her traveling companion and Bob and his studio representative booked in at the local hotel and ran into Herb Jeffries. He was doing a stint at a local club to help out the owner who had befriended him when he needed it. They made a deal. Herb would appear on their Marine show the next day and they would appear at the small night club that night and give the place a boost. That night the place was full of smoke, on-leave Marines and their dates. Jane and her companion left. Bob and his studio friend stayed on. Pretty soon, all the girls were running over to Bob asking for his autograph and frankly flirting. The Marines, suddenly bereft of dates, started muttering and looking decidedly dangerous. Mitch cased the situation and said in a very loud voice, “Look, girls, this is very flattering, but these boys could tear me apart. Now you go back to your tables and when you get a Marine to come over here with you, I’ll do anything you want me to.” The girls went back to their dates, the Marines subsided and eventually Herb Jeffries sang.

Mitch is completely aware of the people around him at all times. While checking out a new individual, he probes, pulls back, makes tentative verbal passes at communication and finally, having the individual pegged, he becomes available for surface friendship. Every leading lady he has ever had speaks with respect and admiration for Mitch. Whatever the personality of the leading lady, Mitch makes himself compatible for the length of the picture. Jane Russell, who turned into a close friend, feels that Mitch’s vision and intellect is way beyond that which is comfortable to the average man. Ann Blyth, indeed a perfect lady, met only a perfect gentleman on the set of their picture. Ava Gardner was grateful that Mitch looked immediately past the glamour girl and saw her as a person and treated her that way.

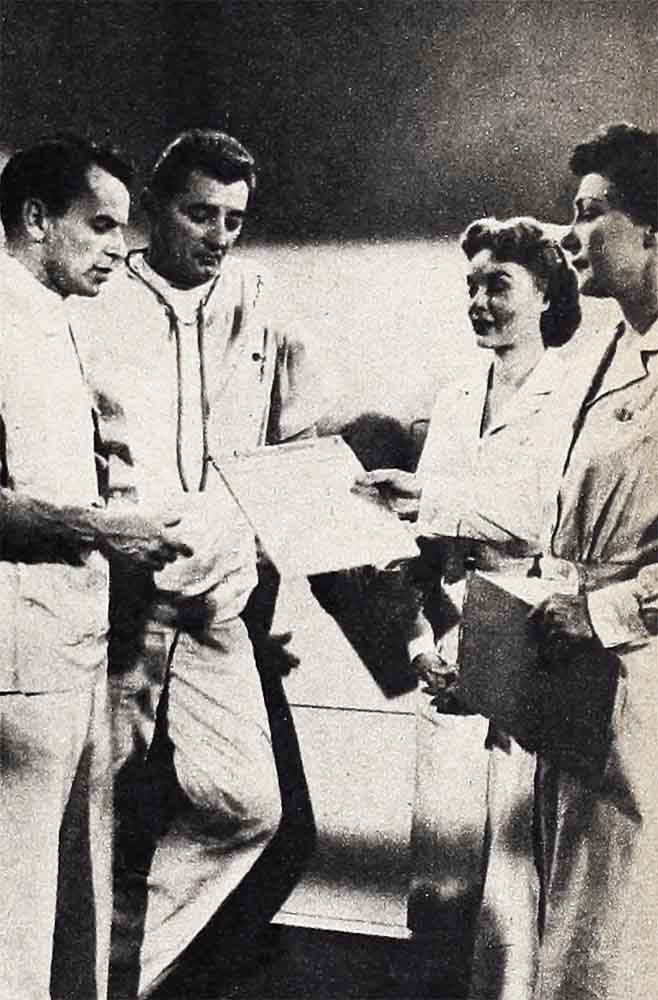

Olivia de Havilland had a ball with Mitch on the set of “Not as a Stranger.” A good sport herself, she and Mitch and Frank Sinatra kept constant gags going. One day, Mitch was standing with an almost empty tin of beer in his hand. Olivia came up straight-faced and opined, “Robert, you will drink beer. Don’t you realize you will become fat and dissipated and ruin your career?” With which she grandly swept the can from his hand. The next day a columnist reported a hot and heavy feud going on between Olivia and Mitch. Something about tossing beer at each other. It made juicy reading, but it didn’t dampen the fun on the set.

Karen Sharpe, recently working with Mitch and Jan Sterling on Sam Goldwyn, Jr.’s “The Deadly Peacemaker,” appreciates him very much Her first day of shooting also happened to be her big dramatic scene. She was working on her ulcer degree, when Mitch suddenly pulled her down on his knee and started gently massaging the back of her neck. He relaxed her completely without one admonition of “Relax, pull yourself together,” or “You’ll be great, kid.”

There was great excitement on the set of Stanley Kramer’s “Not as a Stranger.” The cast and crew knew they were putting together a great motion picture. Mitch was there as the doctor because Stanley Kramer believed he was right for the role. He had many opinions offered to the contrary. The challenge of creating the very best touched them all. There are performances in this picture which will make a lasting impression. Mitch certainly made a lasting impression on Stanley Kramer. He said, “Bob, in my opinion, is one of the finest actors in the motion-picture business and perfect in ‘Not as a Stranger.’ This will prove beyond any doubt his capabilities. I cannot praise too highly Bob’s talents. He is an asset to any picture.”

When “Night of the Hunter” was still only in book form, Paul Gregory, producer, and Charles Laughton, great actor turned director, rang the doorbell of Mitch’s home, book in hand. As far as they were concerned he was the only actor to play Preacher, the psalm-singing hypocrite. Mitch read the book and became so enthusiastic that he cornered friend after friend to read excerpts from it. To some he read the entire book. He wanted to do Preacher. Four weeks before the picture started he knew every line of the script.

Charles Laughton was greatly affected by the performance. “Bob is one of the two finest actors I’ve every been around. His was an extraordinarily brilliant technique. It was his own performance—not mine—his own interpretation. We understood each other from the start. He is extremely shy and he knew from the first that he could relax with me. Directorially, I didn’t try to pull it out of him. I built a wall around him, so he could let loose, and enabled him to give what he had to give. I’ve seen the picture now a dozen times in various stages of cutting and mixing sound, and I’m never bored with his performance. It’s exciting and brilliant.”

Two of the finest men in motion pictures have made unqualified statements about Bob’s greatness. Other directors and actors will tell you the same. And yet Bob, without blinking an eye, will say glibly, “This is a job, like any other. The better I get at my craft, the more money I pull down. I’m not a movie star, I’m an actor. I’m not a freak. I’ve got a job to sell a product. When I was under contract, I was on salary. Now that I’m free-lancing, I’m on commission. The product has to be even better. Recently I started on a participation percentage deal. That means my initial investment—me—has got to be good or the product won’t sell.” That may sound all right at first glance, but Bob is not a businessman.

This matter-of-fact business approach is another Mitchum maneuver to turn the spotlight away from his true feelings. In “Night of the Hunter,” he played the hypocrite, praying to the Lord and dealing out hell on earth with an enthusiasm that was sometimes terrifying. Hating hypocrisy, he poured out all of his venom in the role. Perhaps it helped him spend some of his inner suspicion, distrust and rebellion in a worthwhile way.

Lately, Bob has begun a painful struggle to put his publicized personality on an even keel with himself. Perhaps his inner knowledge of his capacity for greatness is being fulfilled by the run of excellent pictures, which will once and for all stamp him a great actor. At any rate, he is beginning to conform. He has accepted the fact that other commitments go with acting. He will lunch and discuss business with an agent, go to parties that are semi-social but really strictly business, and appear at events he feels are a part of his profession. He is less apt to throw a verbal haymaker at a direct and personal question. Though habit is strong, he has not tom off into the wilds by himself for some time. The need for that devastating aloneness is lessening. After the “Deadly Peacemaker,” he was working out a quick vacation. He vacillated between Mexico, Las Vegas and Lake Mead, but there was a difference. Dorothy and the kids were going along for the Easter vacation. The restlessness is changing to real wanderlust. He has always loved new places and new people; just the motivation is changing.

There’s little doubt that some of the old Mitchum will always remain. There will be abrupt rebellions, startling statements and fevered violent action. But the turmoil within this sensitive, brilliant, brash rebel is lessening. His inner fight for peace is slowly taking shape. The great aching void of loneliness that ran away with a six-year-old boy is being filled. He is feeding his own children the love and attention and belief in man that he searched the forty-eight States to find. His own hunger is being appeased in the teaching. And slowly he is learning to give of himself.

Robert Mitchum can be one of the greatest men in our industry. Many people today think of him as a near-genius. It’s time the many people who do not know him are let in on the secret. This is the to-date untold story of a misunderstood man named Bob Mitchum. A story we think you’ll agree should be known.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1955

AUDIO BOOK