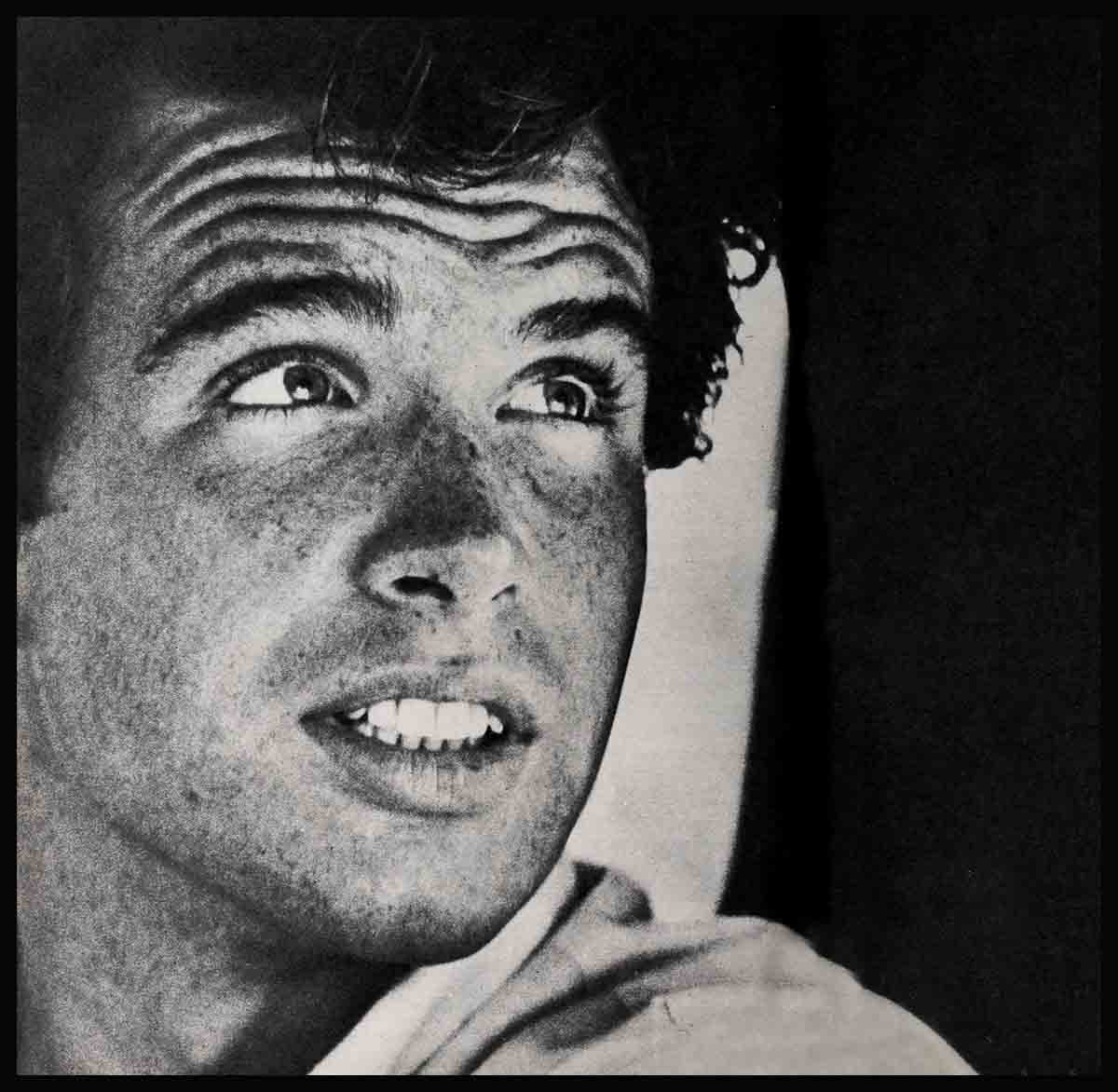

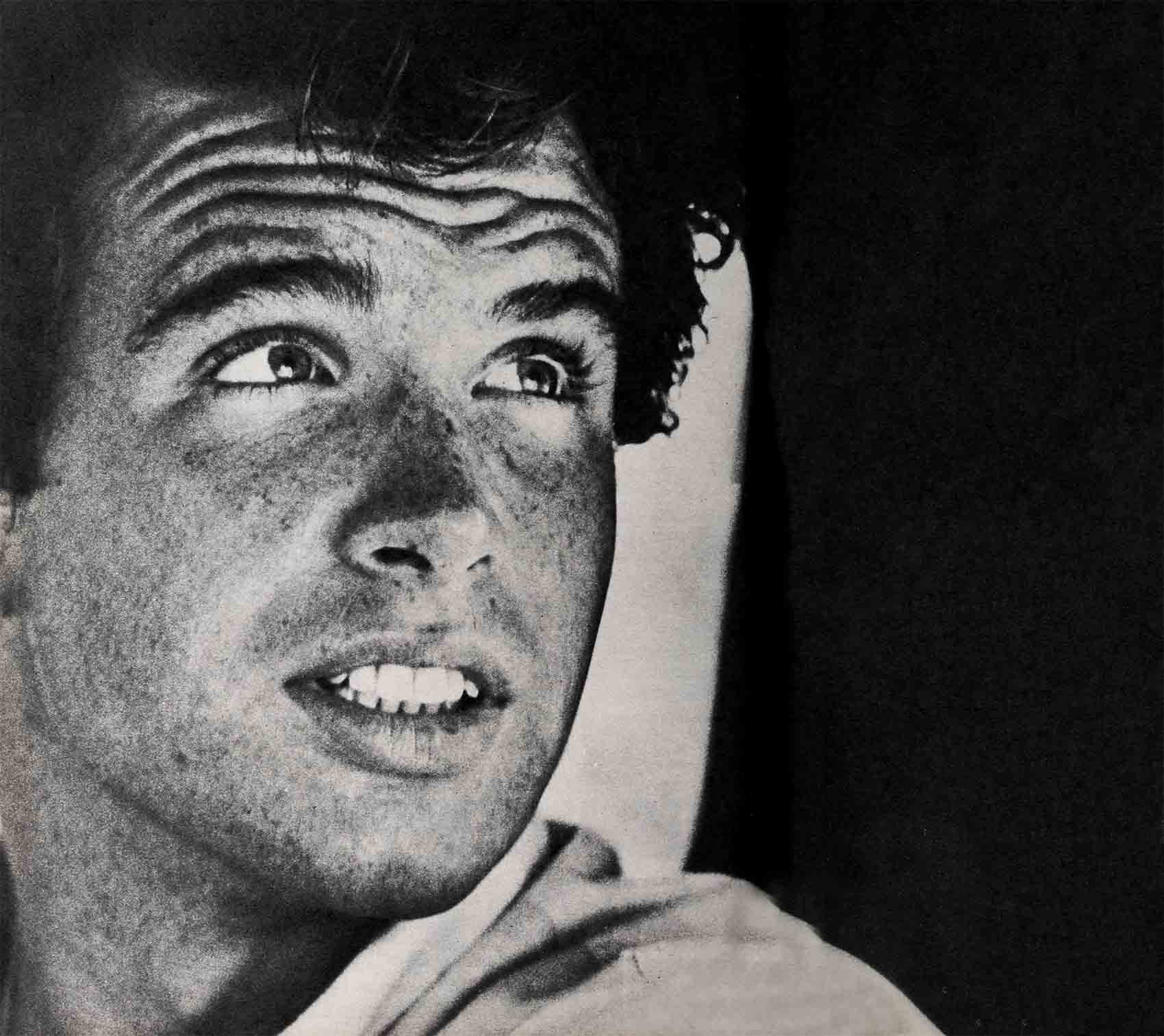

What Are You, Warren Beatty?

The other day an ostensibly self-assured, cocky Warren Beatty, a casual grin on his face, resumed his movie career. He had not made a picture since September, 1961, when he completed “All Fall Down” at M-G-M. Was he really so sure of himself now? Was he rusty? Was he frightened? Did he care what his co-workers are saying about him? In this rare interview, Warren has a lot to say, frank, shocking, no holds barred. And so do the people on the set of “Lilith.” As for being rusty, Warren’s own reaction is: “You can’t kill talent. If you have it, you have it. It doesn’t wear out. Nor can you destroy it by not calling on it.” His director, Robert Rossen, feels that “after one and a half years of inactivity, this boy is like a young horse who shies at the sight of a saddle. He’s uneasy. Let’s face it, Warren is rusty. He has to ease himself into acting and regain his confidence . . . Is the boy any good? Of course he is. I wouldn’t have paid the stiff price for him if I didn’t believe in him as an actor. And I can’t really blame him for wanting to be paid as much as the best. He sees what Natalie Wood is making and he knows that his si ster isn’t working for chicken feed either, and he is a proud boy who insists on equal terms. After all, they are in the same crowd. And if he ends up driving a hard bargain, well, that’s acting.”

As he was speaking, a lonely figure appeared from the direction of the house and walked slowly to the trailer window, and past it. Several yards beyond it, Warren Beatty turned and just as slowly walked past the trailer again, looking at the ground. “I suppose he wants to talk to you,” I said. “I guess so,” Rossen said, excusing himself, “I’d better go out to him.”

The two men stood on the sidewalk talking, Warren Beatty pointing to a sheet of paper, Rossen talking back and waving his arm to prove a point. Somehow, they looked like a college student getting sidewalk instruction from ,a college professor. After a while Beatty nodded and walked off towards the house with the film crew, and Rossen came back. “Where were we?” he said to me.

“What did he want?” I asked. Beatty had been worried, Rossen explained, about an added line the girl’s husband was going to say to him in the scene. It was about his mother having become insane before her death. Dropped casually, unintentionally, but hitting the boy below the belt. “This proves the point I’ve just made,” Rossen said. “He is a good, conscientious actor. He knows his reaction to this line is important. He wanted to know exactly what emotion to register. I told him, the way you feel when hit unexpectedly in the stomach. He’ll spend the next hour or so prior to the shooting, going over this business, again and again. Now if you ask me why I chose him for the role, I’ll say because of this. And because he looks like the character in the story. Tall, strong and masculine, the lad who can have any woman yet finds himself drawn inexorably to the girl in the institution, and becomes obsessed, gradually enslaved. Others suggested Tony Perkins for the part, but he would have been wrong the way I see it. And so it’s up to Warren Beatty to prove that I was right.”

“Is he frightened?”

‘‘Well, I’m helping him not to be.”

The evening before, co-star Peter Fonda had said, “I’m only twenty-three and Warren’s twenty-five, but he’s the frightened boy, not I.” Now it was beginning to make sense. “He’s unsure of himself,” Henry Fonda’s young son said, “and we actors sense that easily. He gambled on making a career on his own terms, and has succeeded so far in getting the highest fee ever paid a new actor with as little experience as his. He’s making $200,000 per picture now. But he can only pray that what he’s doing before the cameras comes off. He’s scared of me, because of my role—which I personally consider the meatiest of all. He shouldn’t really, because I wouldn’t care to up-stage him. I’d simply like to do my job, and let him do his. But then, he is Warren Beatty. To him there is nobody else. He simply has to be good. This has to be his picture. But this girl of ours, Jean Seberg, is good, too, and he knows it.”

Since Warren’s last film, he had been living off his earlier earnings. Having received all of $15,000 for his first movie, “Splendor in the Grass,” opposite Natalie Wood, twice that much for his role opposite Vivien Leigh in “The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone,” and four times as much for “All Fall Down,” with Eva Marie Saint, he had grossed over $100,000 in less than two years. Not bad for a young man, even in fabled Hollywood.

He had read and turned down over fifty movie scripts, including “The Leopard” and “PT 109.” He picked “Youngblood Hawke” at Warner Bros, as his next vehicle, stayed with it through the preparatory stage, walked out on director Delmer Daves and co-star Suzanne Pleshette on practically the very eve of filming. The studio then rushed in a total unknown, James Franciscus, to replace him. It was then that Beatty reported for duty in “Lilith,” which was a picture he had previously agreed to do following “Youngblood Hawke.”

And how did Warren handle it?

“I called Rossen,” he tells you, “and told him my schedule had been changed, that I was ready for him. When could he start? He said he could start tomorrow. So I said okay, let’s go.” Warren Beatty was ready.

The next day Beatty collected his meager belongings, dropped off the key to his rented Hollywood house at the office of his business manager Ed Traubner, told the car rental office to pick up his rented car in front of the house, and had his press agent, Mike Selsman, drive him out to Los Angeles Airport. The period of inactivity was over. He was reporting to work—at an estimated $20,000 for each of the next ten weeks.

Behind him, in the Hollywood he had invaded not much more than two years earlier, young Beatty had left practically nothing, if one doesn’t count Natalie Wood.

“Warren doesn’t believe in owning things,” agent and buddy Selsman explains. “He’s always told me that an actor has to be free.”

In line with this philosophy, Warren has refused to acquire anything of value, even such minor things as a radio or record player. When he dis- covered that the house he had picked to live in—on St. Ives Drive, with a commanding view of Hollywood at his feet—didn’t have a television set, he didn’t give it a second thought. He didn’t even bother to rent one.

The house did have a phonograph and a couple of radios, and a swimming pool, and that was good enough. As electric bulbs burned out he didn’t bother to buy new ones, with the result that when he left there was electric light in only two rooms. “He does buy books and magazines,” Selsman says, “but he doesn’t think of them as property. He leaves them behind. But he isn’t messy. House owners never sue him for damages after he leaves. And he eats or drinks anything. Let’s say he’s casual. . . .”

The word casual kindly applies to almost everything Warren Beatty had done during his period of inactivity. He casually escorted Natalie Wood around town, to Hollywood gala soirees, premieres and other affairs; he casually signed autographs. And just as casually he declined to be drawn into conversations concerning his relationship with Natalie—“Why don’t you ask her?”—or about his sister Shirley MacLaine, who is three years his senior.

By the time Beatty was gone he had left a strange imprint on movietown. He had become a real life Jimmy Dean of “Rebel Without a Cause,” had made few friends and a lot of enemies. He has succeeded in agonizing the high and mighty at the movie studios by snubbing them, their edicts and their offers.

Why did he stay, then, all this time in a town he had seemingly set out deliberately to snub? According to some, it was part and parcel of a young actor’s strategy to get recognized. Indeed, as time wore on, the former TV player who had done anything from “Playhouse 90” to “Dobie Gillis” was beginning to get offers ranking in price with those submitted to a Montgomery Clift and a Tony Perkins. His unique quality, a blend of the aforementioned Clift and Dean, made him stand out and desirable among others of his age. He knew it, and made the most of it. But both Traubner and Selsman vehemently deny any intention on Beatty’s part of “sitting out” for a higher price.

“Warren received well over one-hundred scripts,” Selsman assures you, “and he read them all, from cover to cover. He’s one actor who reads the submitted scripts. And quite a few of them had a pretty lavish deal attached. . . . But Warren didn’t like any of them. The price had nothing to do with it. Eventually, he liked the two properties Robert Rossen owned, ‘Cocoa Beach’ and ‘Lilith,’ and they reached an agreement. Warren makes a point of believing in a director. He had seen Rossen’s movies. He thought a lot of them. So, when this came about, and ‘Lilith’ was first to roll, Warren went into action. It was as simple as that. That’s all, as simple as that.”

Over in Rockville, the Maryland town where “Lilith” was being filmed, Warren Beatty was seemingly the same totally uncompromising actor let loose in a beautiful countryside of rolling hills, forests and lakes. If what he had worn in Hollywood had been a mask, it had in the year and a half grown to his face. I had gone to Maryland to watch young Beatty before the cameras, and I began to sense the truth when, on the day following one of lavish hospitality to press photographers, not only they but even the film company’s own staff man was barred from the movie set, because on that day Beatty was doing a “difficult” scene.

Beatty, playing the part of the hero of the morbidly sensual J. R. Salamanca story about love in an insane asylum, has wandered off to see his old girl friend. He is welcomed into the house where he meets the girl’s husband, senses the girl’s loneliness when left alone with her but refuses to accept her veiled advances.

On this particular day the shooting was limited to the first phase of the encounter, the boy’s wandering onto the porch of the beat-up, drab house. A light drizzle was coming down to give the scene the right mood. “No picture taking today,” the assistant director screamed at a press photographer who was spied venturing onto the scene. “Why?” the press photographer inquired. He was told: “Orders.” Out on the sidewalk, Beatty was slowly walking up and down. His face was expressionless. The crew was setting up the movie paraphernalia. The assistant director watched the photographer disappear down the street. “That’s better,” he said.

“Yes, I gave the order,” Robert Rossen said quietly as he looked out of the window of the automobile trailer turned into a mobile study for the picture’s director. From the window, we could see the crew at work on the lawn in front of the street, and up on the roof, setting up lights and reflectors. “I want to give the boy his chance. I want him to feel unencumbered and free. No Peeping Toms. No interruptions. And I’ll take him through this sequence slowly, step by step, in three days of shooting.” Little wonder the boy thought a lot of Rossen’s methods.

When I went to talk with Warren Beatty, he was sitting in his little dressing room cubicle at the far end of a huge green company trailer. He was alone. The day before when I came to see him, a cardboard dangling outside from the doorknob read, “I’m sleeping. Don’t Disturb.” I “disturbed” him just the same, to find him in company of three young girls.

They were not my cup of tea, but he seemed to enjoy their company immensely. The girls had arrived on the Rockville location by themselves, identified as “Mr. Beatty’s Friends,” had taken a room in the same gigantic roadhouse-motel the entire movie company, including Beatty, had been staying in. The uneven foursome then spent the evening together. Beatty didn’t expect to be busy the following morning but sudden rain caused Rossen to switch scenes and to tackle the visit sequence at a moment’s notice.

“Come in,” he said. We had only recently renewed a vague acquaintance which dated back a couple of years ago, highlighted by our once being placed side by side at a Hollywood banquet. On that occasion he was accompanied by Natalie Wood and during the several hours we spent together at a round banquet table for ten—the others included Janet Leigh, Tony Franciosa and his wife, Barbara Rush and her husband, and Maximilian Schell—Warren spoke perhaps twice. He and Natalie just sat, occasionally whispering to each other. When the waiter came over to collect the banquet dinner tickets, Warren squinted at him in surprise, demanded, “What is that?” Being one of the hosts, I happened to have a couple of spare $25 tabs on me and gave them to him. “They came with our invitations,” I said. “Oh,” he said. He handed the tickets to the waiter and turned away, to Natalie. So far as he was concerned, the incident was closed. From across the table Janet Leigh winked an understanding eye. Schell smiled. . . .

“I’m so bloody tired,” Warren Beatty muttered. He was sitting on the edge of the dressing room couch having just completed his lunch—a plate of spaghetti and ham. “I didn’t go to bed much before 3:00 last night.

“I’ve been here since dawn and it’s lunch time and, believe it or not, we haven’t filmed a single scene yet.” He fell back onto the couch, thrusting his arms behind his neck to cushion his head. For a while he just lay there, staring at the ceiling and saying nothing. A crew member peered In, and he asked the man to bring another plate of lunch—for his visitor—and two orders of tea as well.

Warren levels

“Tea okay?” he asked. “Okay,” I said. The man disappeared. “I don’t like interviews,” Warren Beatty said, turning back to face the ceiling. “They always want to give me trouble.”

“It’s part of being a star,” I said. “Isn’t it?”

“To tell you the truth,” he said, “I dislike this movie fame.” His lips curled into a contemptuous smirk. “There’s a cheapness about it. It even smells bad. It has nothing to do with your merits as an actor. It’s a freak. Unfortunately, it’s important, too. You find it out, sooner or later, and if you don’t, they tell you. Gradually you learn to think of it as a necessary evil, necessary career-wise. So you accept it. But the loss of anonymity is difficult to take. Painful. Makes you swear at the world, and you do.”

“Are you afraid?” I said casually.

“I am afraid of nothing.” he said, his face not moving a muscle. The Beatty face is big and strong, full-face and profile.

“Aren’t you a bit rusty after a year and a half of not acting?”

“I’m nothing of the sort.”

“Then what are you?”

He gave me a quick appraising glance. The Beatty eyes are quick, alert, suspicious. He turned back to the ceiling. “Frankly, I don’t know what I am.” He was speaking slowly, as if searching for words to express a thing he himself didn’t quite understand. “I really don’t know. I have to find out.”

“How do you find out?”

“By doing this picture. But I don’t know if it’s the right one. I’ll see.”

“Who advises you?”

“Nobody advises me. I advise myself.”

“How old are you?”

“I’m twenty-five.”

“Isn’t it a bit presumptuous of you to so fully rely on yourself? You’ve had limited experience.”

“I rely on my instinct. It’s just as good.”

“Was it as good when you picked ‘All Fall Down’?” (It had not been big box office.)

“I didn’t pick it. I had to do it. I had a commitment. But after it I was free. That’s when I sat back and waited for the right picture to come along. I read all those scripts and hated each and all. Finally I thought I liked the one at Warners, ‘Youngblood Hawke,’ and agreed to do it. It was a mistake. You can’t judge a movie by a script. A script is just so many words. In the end it’s how you say them and what you do that matters. Which means that you stand or fall with your director. I didn’t know Daves. I had never met him before. Then we got together and worked together, and I contributed a lot, and after a while I realized that it was all wrong. We were having differences. I couldn’t do the picture. We parted company but it was never over money or contract privileges as the papers wrote.”

Faith and doubt

You lost faith in your director?”

“I told you. I never knew Daves before.”

“But you knew Mr. Rossen?”

“Yes. And I liked his work. That’s how we got together.”

“He’s an excellent director.”

“Is he?”

“Why, do you have doubts in him too?”

He pressed his lips together in an adamant gesture, then relaxed again.

“We’ll see.”

We remained silent for a while. The man brought in my lunch and tea for two, and some fruitcake, and Beatty sat up to sip his tea and eat the cake. Whatever I knew about him before had come into sharper focus with the realization that behind the independent front hid a boy who didn’t quite know who and what he was. However agonizing his self-appraisals, he wouldn’t show any of it to the world. So, his defense had to be attack.

“You could have waited longer than just a year and a half, couldn’t you?”

“I could,” he said nonchalantly, stretching out on the couch again. It was then that he made his pronouncement about talent: “You can not kill talent.”

Warren went on slowly, “But there comes a time when one has to start making money again. Then, even though the script may be very much like the fifty you had turned down, you find yourself accepting it. That’s what really happened to me in the case of ‘Youngblood Hawke.’ I saw Rossen’s script earlier. I didn’t dislike it but it needed changes. So he said he would change it. And later he took me to Paris to look at some prospects and he had me meet Jean Seberg. He picked her for the title role and I said okay. . . .”

“I’m not impressed!”

He was being very cocky but it was par for the course, even his disrespectful insistence on omitting the word “Mr.” from the names of the directors he had agreed to work for.

“They tell me that you prefer European directors.”

“I don’t. There’s one Frenchman, very young, by the name of Truffaut who had made only two or three pictures but he is very talented. I’d like to work for him. But I am not impressed with the others. Not everybody agrees with me. But this doesn’t mean that I have to agree with the others.

“I don’t think that any director is better than Elia Kazan who put me into his picture and made me into a movie actor. I respect him more than any of them. And I’ve seen most of their pictures, and I’ve talked to many of them in Europe last year, and on occasions when they came to Hollywood. and I am not impressed.

“Is there anything you’re impressed with?”

“I don’t know.”

“Do you like being a movie actor?”

“I don’t. To me, movie actors aren’t much more than animated mannequins taking up a prescribed position a dozen times a day and then going through the same movements until the director calls ‘cut’ and the mannequin comes to a stop. But I shouldn’t say these things about them. I’m one of them now. And I’m finding ways of not being a mannequin.”

“You’ve also become part and parcel of Hollywood, haven’t you?”

“I don’t knock Hollywood anymore. I guess I have changed. It isn’t what Hollywood has. It’s what it has not. As a community it lacks a lot of things, but so does Juneau in Alaska, or Rome in Italy. Every city lacks something. After seeing quite a few places in the world I find that Hollywood is among the prettiest. And right now I don’t belong anywhere but I feel very much like buying a house there and making it a sort of home base even if I don’t expect to be there much during the next few years.”

“Could you make it your permanent home?”

“I guess I could. Hollywood isn’t worse than any other community in the world where talk among men is what girls they have seduced.”

“I understand Natalie has just bought a large house in Beverly Hills. Does that mean that you are splitting up? Or do you mean her house?”

He sat up, the pupils of his eyes growing dark: “You want to make trouble for me?”

“I don’t. You don’t have to answer!”

He remained in a sitting position, staring at the wall.

“You’re a strange guy, Warren,” I said. “I guess you’ve been told this many times before. And you want to have your pie and eat it. Sooner or later you’ll have to compromise. Your sister told me that apparently you are determined to live on an island of your own. In the middle of all of us. She tells me that it reminds her of the walk-in wardrobe closet that you had in your room in your parents’ home in Arlington, Virginia. You put a desk and chair into it, and fixed it up with a light, and you spent much of your time there. Nobody was allowed in.”

Two years earlier, Shirley MacLaine had told me this story about her kid brother who, like Garbo, insisted on being alone. During his last year at high school he gave up football to play the piano at which he excelled, and still later, after a boring semester at Northwestern University in Chicago, he fled to New York to play piano in a 58th Street honkytonk and eventually entered Stella Adler’s drama school.

He supported himself as a bricklayer’s helper and as a construction worker in a tunnel under the Hudson River but eventually won his first small part on live New York TV. This led to his first lead in a live television play, “The Curly-Headed Kid.” Then, in quick succession came more TV plays, summer theater and a chance to read for Elia Kazan. According to Shirley, Warren got seriously interested in acting at this point. Until then he was merely “messing around.” He also grew moody, unpredictable, and whatever little contact there was between brother and sister shrank to practically nothing. Warren withdrew into himself and even his name was not to be a clue to his identity as Shirley’s brother. Hurt by his attitude but ready to rush to his aid if he were ever in trouble, Shirley decided that the closet was a clue to the Warren Beatty character.

A remote feud

An amused glint came into his eyes at the mention of the closet: “Is that what she says? About the closet?”

“Yes. Is it true?”

He grinned: “It’s her story . . .” Then, mellowing. “It is.”

“Why don’t you get along with your sister, Warren?”

“Those stories aren’t true. I’m not feuding with her. We’re remote, that all. I talked to her by phone last New Year’s Eve.”

“Who called who?”

“She called me, of course.”

“Why ‘of course’?”

“Because I never call. My sister or anybody. It’s my nature.”

There was a knock on the door and he said, “Come in.” It was the medical nurse assigned to the film company.

“Your shot, Sir.” she said, opened her bag, and produced a hypodermic needle.

“I’m taking vitamin shots,” he said casually by way of explanation. “It’s so much more effective than swallowing pills.”

“We’re ready for you, Mr. Beatty,” the assistant director yelled into the open door.

“Keep your shirt on,” said Warren Beatty. “Let me get my pants on first.”

THE END

—BY HENRY GRIS

Warren’s next film is “Lilith,” scheduled for a spring release by Columbia Pictures.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1963

zoritoler imol

3 Ağustos 2023Greetings! I know this is kind of off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could get a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having trouble finding one? Thanks a lot!