The Day Fate Smiled

They did not run to meet him. That was the frightening thing. Always before when he had entered the house—even if it were Fred MacMurray ell but retired from public life only after a day at the studio—they had come laughing, eager, in happy rivalry to see which could reach him first. Now they stood rather too close together, the girl just into her teens, the boy younger and—waited. It was long past their bedtime. They had been waiting for hours. But not to greet him this time—rather, to know if what they had read in the newspaper and heard on the radio was true.

He glanced involuntarily at the nursemaid who stood a little apart, and she gave him a helpless look which meant, “I tried. But you know how Susan loves to read the paper. She saw it before I did. I’m sorry.” He gave a little nod, forcing back the bitterness he couldn’t help feeling. It wasn’t her fault—it wasn’t anyone’s fault, really. Unless, maybe, it was his own.

With that thought hurting him, Fred MacMurray crossed the room to his children. He dropped to his knees, putting an arm around each, holding them close. “Susan—Bobby—” he said huskily. “I’m not married. Don’t you know I wouldn’t marry anyone without telling you first? Don’t you know I couldn’t do a thing like that without consulting you?”

At almost the same moment, in her own home across Hollywood, June Haver was talking to a reporter on the telephone. Imminent tears thickened her voice as she said, “It simply isn’t true. It’s all a silly, embarrassing mistake. Mr. MacMurray and I aren’t married—we’ve never even discussed marriage. I’m not sure we ever will . . . now.”

She hung up and turned away from the telephone—knowing that at any moment it would ring again, commanding her to issue still another denial. And knowing, too, that since denial never fully catches up with rumor, perhaps it would be better never to see Fred MacMurray again. Alone, June faced again a time of decision. Would it be hard for them even to see each other at all? Would there be, between them now, an almost impenetrable wall of embarrassment? How could these two adults face and hurdle this new obstacle?

Theirs was not the ordinary Hollywood romance, which takes publicity almost for granted, laughing off the gossip columnists and photographers. Their own characters and their own lives—the intimate acquaintance of both with sorrow—made that impossible.

Without the tragedies which had come to each, it is unlikely that Fred MacMurray and June Haver would even have met, except casually. When June first arrived in Hollywood, Fred was already an established star. They worked together in “Where Do We Go From Here” and saw each other at occasional parties or premieres—not many, because Fred and his beloved wife Lillian seldom went out, preferring the comfort and privacy of their own home in Brentwood. The MacMurrays did not make headlines—they were too deeply in love, too content with each other, their children, their few close friends.

It was June who made the headlines. Young, with a fresh blond loveliness, her singing and dancing had lifted the hearts of millions almost from the release of her first picture. She was news. Her dates were news—with Farley Granger, Victor Mature, David Rose—and it was big news when, in 1947, she unexpectedly eloped to Las Vegas with a young trumpet player. His name was Jimmy Zito, and he and June had known each other when she was fifteen and he was seventeen and they were both in Ted FioRito’s band, June working as the featured singer, Jimmy as a musician.

Almost from the first, June knew that her marriage was a mistake. Except for their youthful friendship, she and Jimmy had nothing in common. He was a stranger to her—moody, subject to fits of silent depression which June could neither understand nor cope with. But she tried desperately hard to stay married. Two weeks after their civil ceremony in Las Vegas, she and Jimmy were married a second time by a priest of the Roman Catholic Church. “I didn’t want to cheat,” June said pathetically months afterwards, explaining why she went through with this religious ceremony at a time when she already feared the marriage wouldn’t last. “If I were sincere in wanting to make a go of things with Jimmy, I knew I had to be sincere in my faith. My priest thought I should give the marriage every possible chance.”

There was no chance. Two months later, June and Jimmy separated. A brief reconciliation followed—then another separation and finally divorce.

Yet, there is no doubt that the whole unhappy experience matured June, made of her a wiser and more understanding person. Proof of this is the fact that after her divorce she was able to resume her friendship with Dr. John Duzik. She had met him some months before her runaway marriage—indeed, there had been some speculation at the time that she and Dr. John might marry. He was several years older than she, a dentist with an established practice in Hollywood, handsome and charming. Even more important, he had the priceless gift of sympathy. To him, June was able to talk out her tangled emotions in the months following her divorce.

John Duzik meant security to June, a cure for the terrible loneliness that comes in the wake of a broken marriage. He meant sunlit days on the golf course, quiet evenings of cards or talk, just the two of them alone or with some friends. He was, too, like June herself, a devout Catholic, and he understood her sense of guilt over the divorce. Understanding, he was able to take some of it away.

The time came when John Duzik and June Haver could look forward to happiness together. She had petitioned the Church to declare her marriage invalid, and there was good reason to hope the petition would be approved. June knew—they both knew—that John was the man she should have married in the first place. “Perhaps we both just had to grow up to each other,” John said quietly, understanding perfectly.

Then, in September of 1949, John entered St. John’s hospital in Santa Monica to be operated on for ulcers. The surgery was successful—yet days went by and the doctors were unable to stop the bleeding. A second operation was undertaken. Still the bleeding continued. John Duzik suffered from hemophilia—a little-understood disease which prevents the blood from coagulating properly. He was, literally, bleeding to death.

For five weeks the doctors kept him alive. It was all they could do, and they did it only by repeated transfusions of blood. The hospital blood bank could not supply such an amount, and a call was sent out for donors. From June’s home studio, 20th Century-Fox, came twenty pints in a single day. From Warners, where she was making a picture on loan at the time, came another twenty-five.

After John’s second operation, when it was recognized how really serious his condition was, June collapsed and shooting was held up on her picture for four days. But the generosity of her fellow workers sent her flying back to the studio—to dance, to sing, to pretend gaiety when desolation was in her heart. Every afternoon, as soon as the day’s shooting was finished, she hurried to the hospital, there to be with John, to pray, to hope, to wait.

Five weeks it lasted—five weeks of a constant vigil, of days of work and nights of prayer. At last, “Daughter of Rosie O’Grady” was completed with the shooting of a production number which. would ordinarily have taken at least two days to get on film. The cast and crew worked from dawn to midnight to finish it in one day—because June asked them to. Because they all knew it was very near the end of John’s life.

She drove straight from the studio to the hospital. They told her John was sleeping, and she slipped into the chapel, kneeling, whispering soundless words of supplication. At dawn, someone tapped her on the shoulder—a nun, saying, “You had better go upstairs.”

He died twenty minutes later, with June there beside him.

She tried to go on, the little song-and-dance girl whose own life, it seemed then, would never hold another song. After a visit to John’s family in Wyoming, she returned to Hollywood and her career. She made pictures, good ones. When a year had passed, yielding to the advice of her family and friends, she began going out socially. The gossip columnists made hopeful notes of each escort she was seen with—Kirk Douglas, Dan Dailey, Sy Bartlett. But she was never seen with the same man many times in a row.

She was, of course, looking for some meaning in her life. She could not find it in dates and parties, or even in work. But she did find it in prayer, in study of religious writings, and most of all, in service to others. In 1951 and 1952, it might have been worth noticing that whenever anyone had a problem, was sick or bereaved, June was there helping as much as she could. Always deeply religious, she turned more and more to the quiet joys of the Church. And in February of 1953, after two years of serious consideration, she announced that she was retiring from Hollywood and entering a convent to study and prepare herself for holy vows.

It was a courageous decision, but a second and even more courageous decision lay in the future.

June left Hollywood. She entered St. Mary’s Academy in Leavenworth, Kansas, as a novice in the Order of the Sisters of Charity. The life of a novice is a rigorous one—sixteen hours daily of study and prayer—and it proved too taxing for her health. Her faith, her longing to serve God did not falter, but her body did. The time came for that second, and more difficult decision, and June faced it in hours of prayer and meditation. At last, humbly, she accepted the realization that this was not the way God had chosen for her to follow. Months before it was time for her to make her first profession of vows, she left the Academy.

Back in Hollywood she tried to take up again the lost threads of her life—the life she had renounced in all sincerity. She knew there would be the scoffers, the doubters who would automatically discount her motives in entering the Academy in the first place. She knew that once having relinquished her high place on the Hollywood ladder of success, she would almost certainly have to start again on a lower rung. All this she was prepared to accept—yet she would have been less than human if in her own heart she hadn’t felt serious doubts and fears, a sense of failure and an understandable apprehension about the future.

Old friends welcomed her home, and their unstressed pleasure helped. She went out on a few dates. Her business manager began negotiating with different studios for the right comeback role. Then, at a party at John Wayne’s house, she met Fred MacMurray—and fate smiled on two very lonely people.

For seventeen years, Fred and Lillian MacMurray had been one of Hollywood’s ideally happy couples. They’d fallen in love before Fred reached stardom, when he was a bit player in the Broadway musical “Roberta” and Lillian Lamont was a beautiful brunette chorus girl in the same show.

It was Lilly who encouraged Fred to take the screen test which brought him his first chance at Paramount, Lilly who sent him alone to Hollywood while she remained behind in New York in case something should go wrong and Fred’s short-term contract would not be renewed. Of course it was renewed, and Lilly joined him on the coast, where in 1936 they were married. After that, Lilly never gave another thought to a career of her own.

Had they known it, their very honeymoon in Honolulu was shadowed by the sadness which was to come to Fred seventeen years later. Lilly caught a cold on the ocean voyage, but rather than spoil Fred’s pleasure in the trip she kept going, refusing to pamper herself with a few days in bed. Neglected, the cold turned into influenza. Lilly returned to Hollywood pale and thin, and within a few weeks was down with a new attack of the flu, this time a serious one. She was laid up for months, and although she recovered, her health was delicate for the rest of her life.

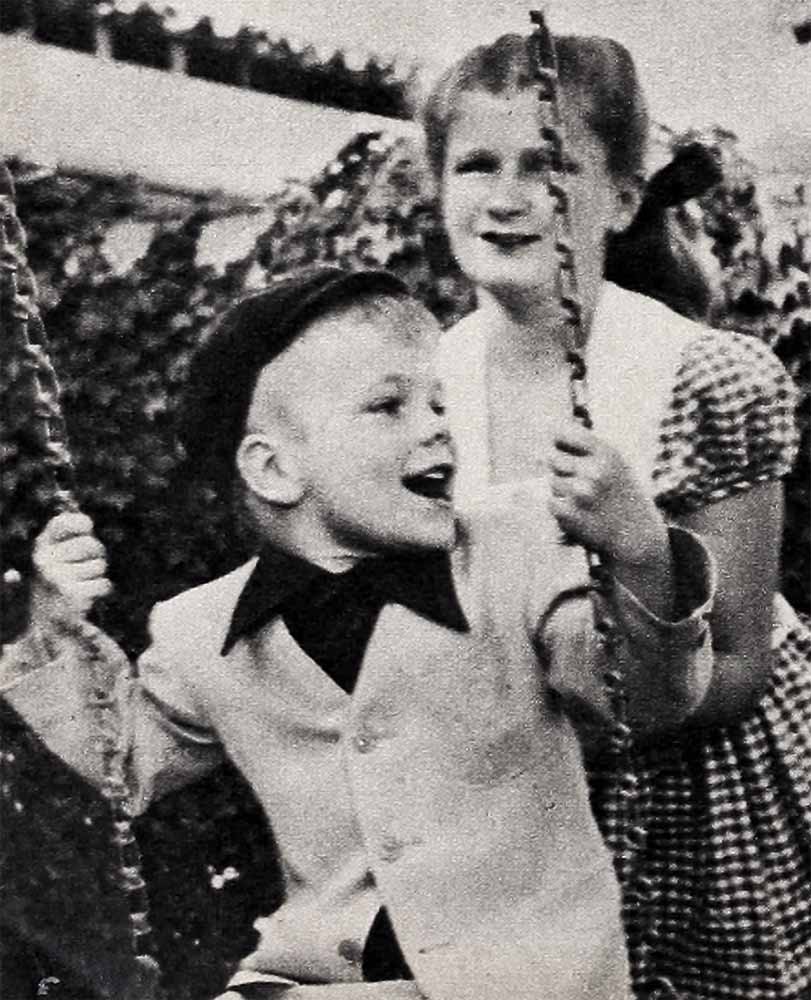

Yet, it was a happy life. Not a whisper of scandal ever touched Fred and Lilly MacMurray. Their love was steady, serene, unchanging. When it appeared that they could not have children of their own, they adopted two—Susan first, then Robert—and loved them. They planned and built their own home on two acres in a quiet section of Hollywood. Their devotion was something of which Hollywood was justly proud.

But that devotion made Lilly’s final long illness and her death doubly poignant. For Fred, when he lost her, there was nothing left except the two children they had both loved. He all but retired from public life, devoting himself to Susan and Bobby. Then, gradually, he came to the realization that grief must be buried inside oneself, that it was fair neither to the children nor himself to become .a recluse. That was one reason he agreed to attend John Wayne’s party—the other was that John was an old friend who needed, because of his own domestic troubles just then, the loyalty of all his friends.

So Fred and June met and were inevitably drawn to each other. Each knew instinctively what the other was seeking—companionship, understanding, sympathy, a chance not to forget the past but to reconcile it with the present. They saw each other again, and then frequently. They found that there was so much they seemed to divine about each other without the need of words—so many experiences they had shared, even though at the time of sharing them their lives had not touched. Together now, they were able to find the quiet laughter they both needed so much.

Their friendship had reached this point when an opportunity came for them to leave Hollywood,’ which held so many memories, and go together to new surroundings. A film festival was being held in Brazil, and both Fred and June were invited to join the party of Hollywood notables attending it. They accepted the invitations: June had flown once before to South America and was able to tell Fred firsthand of its beauty, its unusual gaiety.

And the trip was gay—so delightful that on the way home they found themselves unwilling to let it end. The plane was scheduled to stop in Panama, which neither had ever visited. It seemed so natural, so right to say, “Let’s stop over and do some sight-seeing.”

The decision was made on the spur of the moment—thoughtlessly. They forgot that their reasons for the stop-over might be misinterpreted, forgot even that for them there could not be the luxury of an unnoticed holiday, no matter how innocent.

While they remained in Panama, the great plane winged on to the United States, carrying with it the rumor that Fred MacMurray and June Haver had stopped in order to be married. Reporters, meeting the plane when it landed, noticed their absence from the party, asked for an explanation, were given the rumor for an answer. It went into type, onto the air. In time, it was flashed back to Panama, interrupting the light-hearted holiday of the two people it concerned. Immediately, they caught the first available plane for home . . . and the denials which must be made.

So Fred held his children tightly in his arms and said, “You know I wouldn’t do a thing like that without telling you first!” And June paced the living room of her home, ready to answer the telephone when it rang again.

But some of the hurt, at least, was lifted from Fred’s heart when Susan turned to her brother and said with grave accusation, “You see? I told you Dad wouldn’t do anything so silly.”

Robert’s eyes were troubled. “Well, I didn’t think you really would either, Dad. But the papers said—”

He knew then that despite the mischance which had seemed like a deliberate betrayal of them he still retained his children’s trust. He knew, too, that it meant more to him than anything else in the world, more even than personal happiness.

It was not quite a tragedy, that completely false rumor which invaded the privacy of two people desperately trying to find their way back to the warmth of human affection. But, in the words of a friend, “It’s a darn shame it happened. The publicity is bound to make them both self-conscious—just when they were beginning to learn to enjoy themselves again.”

Can they overcome the damage which idle gossip has wrought? Or will this experience draw them closer together, renew their efforts to handle their lives with as much dignity as possible—but with the honest conviction that two people have the right to find happiness in each other’s company? No one can say with certainty—June and Fred perhaps least of all. But it is very much to be hoped that they can. If two people ever deserved the good things of life, they do—and together they could find them. The children who mean so much to Fred would certainly mean as much to June, were she to become his wife. She has always been passionately fond of children and longed for some of her own. The pace of their lives, their beliefs and ideals would fit extremely well.

It may happen. Fate smiled on them once. She may be kind and smile again.

THE END

(Fred McMurray’s currently in “The Caine Mutiny.”)

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1954