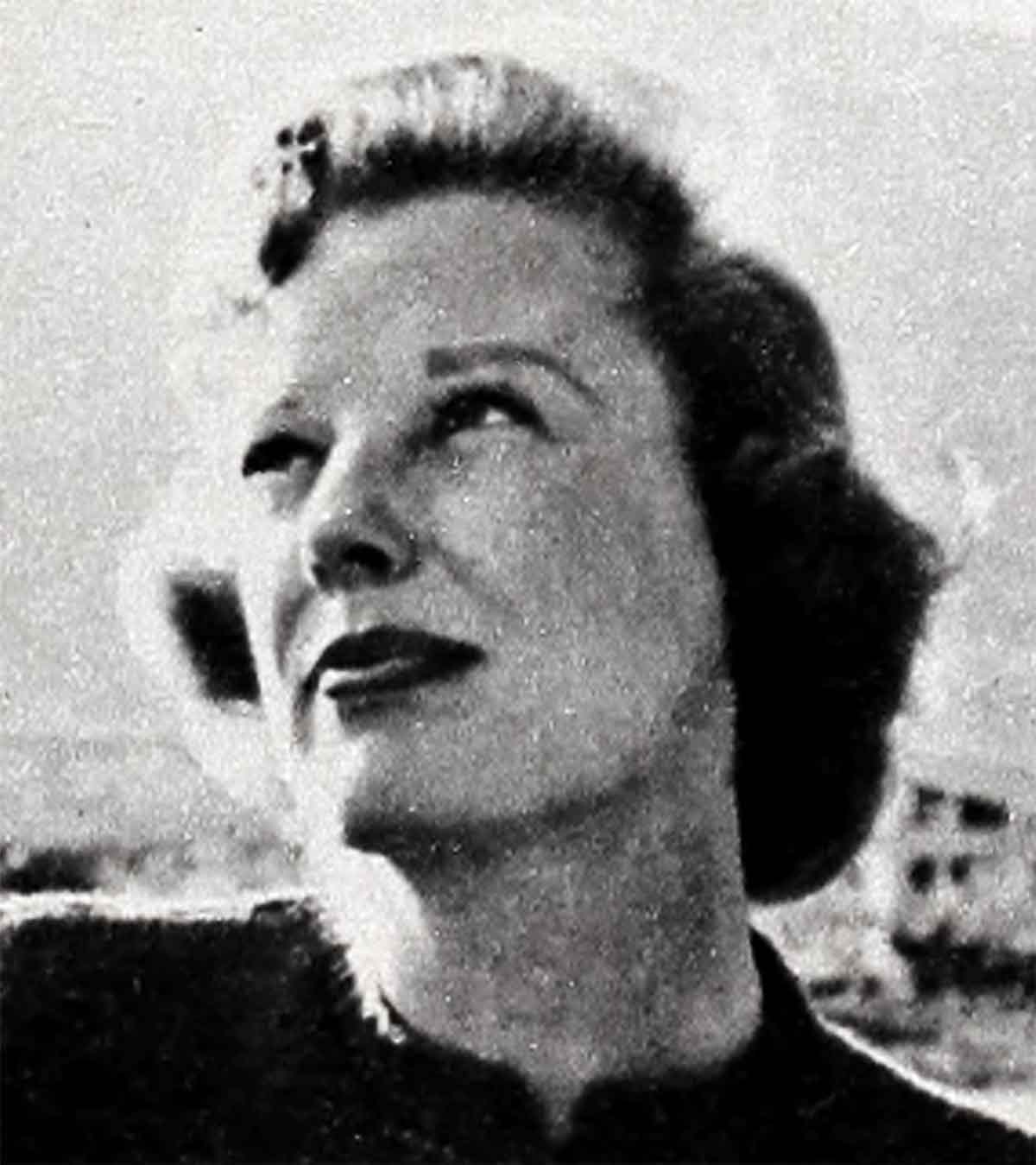

She’s Nobody’s Baby Now!—June Allyson

The farm, home-place of June Allyson and her Richard, is a two-story New England farmhouse, built of fieldstone and stout oak, solid and beautiful, sitting in its 58 acres that includes a private lake atop a mountain in Mandeville Canyon, some few miles from Beverly Hills.

In the spacious living room, done in highly polished maple with antique copper utensils, a yellow love seat faces the tremendous stone fireplace. On this love seat Richard loves to take his ease. And on Richard’s lap, as he takes his ease, June loves to take hers. In moments of excitement, elation, doubt, depression or just because “It is my favorite sitting place,” June can usually be found—curled, kitten-size, on Richard’s lap.

The other evening, a matter of weeks ago, June leaped up to answer the telephone on the small bar to the right of the fireplace.

“Oh, Harry!” Richard heard her say, her furry voice rising to a lilt. “I don’t believe it, I just don’t believe it!”—and then the receiver was hung up and there was a rush across the room and June was on Richard’s lap again saying, “Oh, Richard, guess what—Jose Ferrer wants me to play his wife in ‘The Shrike!’ That was Harry, Harry Friedman of MCA on the phone, Harry says he thinks Elia Kazan was the first to say I should be the wife but that Jose Ferrer has gone all out to get me! Jose Ferrer’s wife in ‘The Shrike’—oh, Richard, I’m so happy!”

Richard looked at her for a moment, then said, “You’re not going to do it, are you?”

“Of course I’m going to do it, silly,” June said. “I’ve known the story ever since Jose Ferrer first played it on Broadway. And I’ve always thought, this is really something I would love to do. But I wouldn’t have asked for it. I haven’t even mentioned it to you, you know I haven’t. Even now I can’t believe anyone would want me to do it . . .”

“Have you read the script?” asked Richard.

“No.”

“Hadn’t you better?”

“Yes,” June admitted. When she read it, she realized it was even better than she had thought. Richard read it and thought it was wonderful, too—but not for her.

“No one,” he said, “will believe you in that kind of a story.”

June bristled a bit. “If I’m not a good enough actress to make people believe me in it, I shouldn’t be in pictures at all,” she said.

“You will spoil the Illusion,” Richard said. June knew what he meant. “The Shrike” would be a complete departure from her previous roles. June would still be a wife, as she was in “The Stratton Story” and “The Glenn Miller Story,” but in this wife-role, she would be destroying her husband instead of helping him.

Specifically, the Illusion refers to the character June has so often portrayed on the screen. Although she couldn’t be classified as a beautiful woman or a glamour girl—even she cheerfully admits that—or as a spectacular dancer or singer, millions of movie-goers believe in her, feel that in Richard’s words “she is what she is—the girl-next-door, the girl every boy likes to have for a wife and every girl likes to have for a friend.

“Dispel that Illusion, tarnish it . . .” Richard said ominously. . . .

Describing the incident later, June says that the turning point in her life came a few evenings later.

“We had a big meeting here at The Farm,” she says. “Richard, my manager and I. Richard talked. He recapitulated his reasons for believing I should not, could not play the wife in ‘The Shrike.’ Finally he came to a period. ‘Would you mind,’ I asked in a small voice, ‘if I talk?’ There was an astonished, this-isn’t-like-Junie pause. Then I talked.

“‘I am not the girl-next-door, I said quietly, ‘not anymore. I don’t think anybody in the world today is the girl-next-door. Or can be. Not I, anyway. How could I possibly be that innocuous or that protected or that good? If I were I wouldn’t, first of all, have a career in one of the most fiercely competitive industries in all the world. I have to sit, remember, in a room with seven or eight executives and hold my own. I’ve got to argue them down or have them argue me down. I have to hold my own. I am holding it now. I have accepted the part in “The Shrike,” Richard. I am going to do it. This is my decision,’ and—

“My Richard drank to me! He rose to his feet, glass in hand and toasted me, saying, ‘Right or wrong, it is your decision, you have made it and I’m proud of you!’

“Now this,” June says, breathlessly, “is really for me quite an astonishing thing!”

The astonishing thing being that for the first time in her married life June dared say “No” to her undisputed lord and master. For the first time in the nine years since she said “I do” to her Richard and thereafter abided, without question, by his decisions, June dared make a decision of her own and on her own.

This personal Declaration of Independence began, June believes, on the day she said goodbye to her professional alma mater, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. She refused to re-sign with the studio which had been “home” to her from the day she arrived in Hollywood to that momentous day last year when—like Gable, the King—she drove out of the M-G-M gates for the last time. For the last time, at any rate, as a contract player.

To do this wasn’t an easy thing for June, but in the doing, she grew up. All the way.

“For months everyone had been telling me,” June told me, “why I should leave M-G-M. I wanted to get out, too, but I wanted someone else to do it for me. I just somehow couldn’t do it myself. When they realized at the studio that I was really and truly thinking of leaving, they were amazed. ‘You’re our little baby,’ they said. ‘Haven’t we brought you up?’

“ ‘You have, you have,’ I’d admit, all choked up.

“They would call me at home and say, ‘You mustn’t leave us,’ and I’d run, crying, to Richard and he’d say, ‘Don’t go there anymore.’

“But they did bring me up,” June said soberly, “and they did pretty well by me and it was my home lot, my only one, but—you can’t stay home too long. In a studio where you are ‘our little baby,’ you tend to remain just that, a little baby, infantile. Everything is done for you, everything is decided for you. They never ask your opinion. They tell you what scripts you are to do, what clothes you are to wear, who is to direct you. They do your thinking for you. They do everything except your actual acting for you. And rightly so—except that you are in danger of forgetting you have a mind of your own which was given to you to use and a pair of feet—on which you are intended to stand.

“In the end, lots of things decided me—the pictures were not good; the contract was up and nothing had been planned for me. I was supposed to do “The Long, Long Trailer,’ which Lucille and Desi did so successfully. We’d had clothes conferences, I’d seen sketches, read the script and no one even bothered to tell me I was not to do it. The way I found out—I read it in the paper! Richard later admitted he’d known for two days before it broke in the papers, but he didn’t tell me. ‘I didn’t know how,’ he said. He knew how disappointed I’d be. And I was. I really did want to do it, except”—June gave a small wiggle of satisfaction—“I did ‘The Glenn Miller Story’ instead!

“In the past year Richard’s career and mine,” June said, “have kind of had a shot in the arm. In different directions. My Richard, who is now directing and producing RKO’s ‘The Conqueror,’ starring Susan Hayward and John Wayne, directs and produces all of his own pictures and he is also an executive producer for RKO. Richard can credit it all to his wonderful marvelous intelligence. He’s the kind who knew, five years ago, exactly what he’d be doing today—and he’s doing it. He also knows what he’ll be doing five years from now. And he’ll be doing that, too. My shot in the arm was that in leaving M-G-M, I all at once found it very easy to say ‘No’ to anybody and about anything. Not only about big, important matters such as the part of the wife in ‘The Shrike,’ but also about all things, large and small.

“Always before, whatever anyone asked me to do, whenever anyone asked me—I’d say ‘Yes.’ My Richard used to tell me, ‘June, don’t always say Yes. There must be some things you don’t want to do!’

“ ‘Oh, there are,’ I’d assure him, ‘but I can’t. I’ll hurt their feelings.’ ”

June grinned at me delightedly. “Now I can. Can say ‘No,’ I mean. When I must. Even to Richard. Can make my own decisions, too. And I’ve done very well so far, though it may seem immodest to say so, in making my own decisions. It was my decision to make ‘The Glenn Miller Story’ at Universal-International. It was my decision to make ‘A Woman’s World’ at 20th Century-Fox—and Richard hadn’t even read the script! Richard, who always read my scripts, used to read them before I did and told me which ones I should, or should not, do. Nor has he read the script of ‘The McConnell Story’ which I’m to do, with Alan Ladd, at Warner Brothers.

“I think this was a wise decison, too,” June said, kitten-faced. “I mean, I accepted the part in ‘The Shrike,’ but I also accepted, and quickly, the part of Alan Ladd’s wife in ‘The McConnell Story’ in which I will be, so to speak, Mrs. Glenn Miller again!

“I’ve made one or two mistakes, of course—I absolutely refused to do ‘The Stratton Story’ and it turned out to be the best picture I’ve been lucky enough to be in! Richard talked me into doing that one. On the other hand, my Richard made a mistake, too. Just one. He told me to do ‘Remains to Be Seen.’ A stinker. During our discussions about my doing ‘The Shrike,’ I’d remind him that he told me to do ‘Remains,’ showing my little claws, ‘so we won’t discuss ‘The Shrike’!’

“Speaking of scripts and such, his own RKO is the only studio in town that hasn’t sent me a script! He doesn’t want me at all, Richard doesn’t. In the studio, that is. I may have to make his decisions for him yet!

“As far as the house is concerned, and the children and any problems concerning them it was always, as with my work, I lived and breathed by Richard’s decisions. . .

“This house, for instance, The Farm. Before we bought The Farm, we lived in a quite large house in Beverly Hills and we’d often sit there and say, ‘This is too big a place for us.’ So we went out and searched and searched and couldn’t find a thing and finally Richard decided we’d build. We had plans drawn up, blueprints and all, and then one day Richard came home and said, ‘Get in the car. I want to show you something.’ And we drove down Sunset Boulevard to Mandeville Canyon and all the way to the end of the Canyon and then, passing through a pair of stone gates, up a winding mountain road. As we were driving along we came to a little cottage. ‘Oh, it’s sweet,’ I said, ‘small and sweet and cosy.’ ‘That,’ said Richard, the guest-cottage.’ Just a little more and we came to the big house, here.

“ ‘Do you like it?’ Richard asked me.

“ ‘Most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen,’ I sighed.

“ ‘That’s good—I bought it this morning,’ said my Richard.

“That’s Richard. I not only would not and could not have chosen a house for us, let alone buying one, I couldn’t even choose a chair, or material for the curtains or wallpaper for a wall until Richard had approved the choice.

“But now when Richard tells me what he thinks about something and I don’t agree with him, I speak right up. ‘I don’t agree with you,’ I say.

“Recently, a little problem came up about Pamela’s school. ‘You should take her out,’ Richard said, ‘put her in another school.’

“I didn’t agree. ‘Richard, you can’t take a little five-year-old girl out of her school, away from her little friends,’ I said, ‘just because of a minor matter that can be adjusted.’ And I didn’t take her out.

“Then there are certain rules I’ve made about the children. I don’t want my children to lose their tempers. When they show signs of doing so, I Take Steps. Let one or the other begin to act tantrummy, ‘It’s so noisy in here,’ I’ll say, ‘I’ll go to my room, where it’s quiet, and you can come to me there and tell me what is the matter.’ Some way or another, it almost always works. In the quiet of my room, to which they come, they grow quiet, too.

“The same punishments don’t work for both of them,” June laughed. “Put Pammy in her room and she sits and sews. Happily. Sit her on a chair and she loathes it. Sit Ricky on a chair, he loves it. Makes faces. Sings to himself. A cricket on the hearth. Now I just say, ‘Ricky,’ and he’ll pucker up his face, run upstairs and punish himself by going into his room.

“In the house there are certain things—records, ornaments and so on—the children are not allowed to touch, certain bottles they are not allowed to open. Richard knows all this, knows all about the symptoms of tantrums and how I handle them and yet when he’s at home alone with them, he allows them to do the ‘verboten’ things.

“The other day I told him about it. ‘Richard,’ I said, ‘I cannot discipline the children if you go against me. Let’s sit down and talk it out.’ And so, to my gratified amazement, he did.

“I suppose it’s because we love each other’ so dearly,” June said. “So deeply. I suppose it’s because we’ve both been faced with the loss of each other. Richard’s illness, when he so nearly died . . . and the days and weeks it took me to be able to believe he was here again, home again, safe again, mine again! And then, just before last Christmas, I had my appendix out and although it wasn’t even slightly as serious as Dick’s nearly mortal illness and I wasn’t the least bit worried, he was terrified, and I was so worried for him. Please, God, I thought as I was going under the anesthetic, don’t let it be as hard for Richard as it was for me.

“I’m glad,” June said, then, “very glad that I now stand up to things and be on my feet instead of Richard’s! Glad I can say ‘No’ when ‘No’ needs to be said. When someone makes a decision for you and it turns out to be right, you don’t feel that you’ve done anything. If you make your own and it turns out right, you feel so wonderful! Even if it turns out wrong—well, you think, I’ll know better next time. And so you will.

“Every time, every time I make a decision of my own, on my own, oh,” June said, stretching to her full, small height, “I just feel so strong and pure!

“I’m glad for Richard’s sake, too, that I can now speak my own mind, make my own decisions. And he’s very glad about it. He comes home tired, he doesn’t want to come home and decide whether or not we need a new water softener!

“Now, at last,” June spoke, real proudly, “he doesn’t need to. Now he doesn’t have to be the husband and the wife!”

At the front door, as I was leaving, June said, as if reciting, “ ‘The Glenn Miller Story,’ ‘The Stratton Story,’ ‘The McConnell Story,’ ” then laughing, “Why don’t you title this story, The June Allyson Story,” she asked, “it is, you know. It’s the story, the Big Story, as of nineteen fifty-three and four in my life!”

THE END

—BY GLADYS HALL

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1954