Velvet Girl

Little Elizabeth Taylor of the inner spiritual radiance and the world’s most amazing pair of dark blue eyes can credit her success to a deep sincerity, a great faith in everything and everybody and the belief that if you want things that are right for you, they’re honest-injun bound to come true.

To her, life is very simple. Things happen because it’s right for them to. And because, when it is right, God pitches in on your side.

That’s why she thinks there’s nothing funny about getting her first screen role at an air raid wardens’ meeting or growing three inches in three months to fit Velvet. It was just right.

Anything she wants very badly becomes a postscript on her prayers. The role of Velvet was a special P.S. that went out from her bedside every night. Her hope of getting King, the horse she rode in that picture, is the newest one tacked on now.

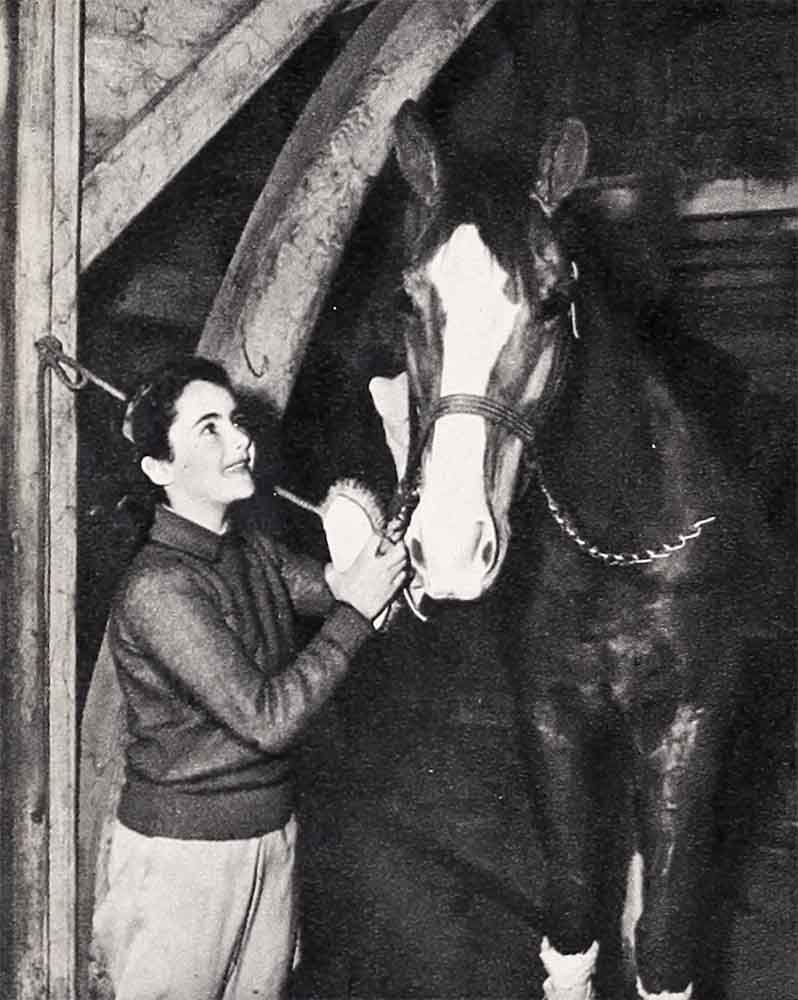

She is in truth a living Velvet— this beautiful little girl whose faith in a horse won her the Grand National in Metro Goldwyn Mayer’s “National Velvet” and gave Elizabeth herself a winning number in the Hollywood handicap. The same faith, warm sympathetic nature and gentleness that is Elizabeth should see her over all the jumps that may lie ahead.

There’s another postscript that’s going out now and that is—“if it’s right”—for her to play the role of Peter Pan.

This, too, is the dream of Clarence Brown, who directed her in her first big success. In the role that made Maude’ Adams famous, little Elizabeth, whose spiritual quality often causes her to be compared with Miss Adams, could step right out of the pages of Sir James Barrie’s “Peter Pan.” But she probably won’t because Walt Disney owns the rights to it and no fairy wands the studio waves in his direction can get it.

Elizabeth loves the role of Peter, the youth who didn’t want to ever grow up, who played on his pipes, dressed in autumn leaves and cob webs and lived among the fairies and animals in the Never Never Land.

All of which sounds pretty wonderful to her. For like Peter Pan she has her own Never Never Land where all things are good and beautiful, where she lives with the animals she loves so much—horses, dogs, cats, chipmunks and more horses. Unlike him, she hasn’t any pipe, but manages to attract so many animals anyway that her parents can hardly get into their backyard for the growing zoo.

She has a Peter Pan-ish quality about her face—an elusive, dreamy, intangible something that you can’t catch hold of long enough to describe. Something that goes along with that Never Never Land and flying over tree tops on the back of the wind. She resembles a dryad, I with her even sensitive features, luxuriant blackish-brown hair, long black lashes and level brows that frame her eyes. Those eyes concerning which Clarence Brown says, “There’s something behind them that you can’t quite fathom—something Garbo had.” And Director Freddie Wilcox telling about interviewing her for her first picture, “Lassie Comes Home,” says that when she walked into his office, “We all took one look I at those eyes and she was in. There’s something behind them. I don’t know. . . .”

Whatever Elizabeth is wearing whenever you see her, she’s also , wearing a long string that’s definitely not a part of any ensemble. It dangles down the whole length of her dress and means that her pet chipmunk, Nibbles, is attached to the other end of it somewhere. Probably on the back of her neck under her thick long hair. The string may dangle from her pocket, inside of which Nibbles is serenely sitting and holding a sprig of red berries in his paws as he has chow. Elizabeth fairly worships the little chipmunk, which she captured while on location with “Hold High The Torch.” The long string is for the purpose of making sure that the tiny creature won’t get lost in the big house or that her black cat, Jeepers Creepers, won’t mistake him for a glamorized rat.

The more you try to talk to her about Elizabeth, the more you find out about Nibbles, about her three dogs, Monty (an English golden retriever), Spot (a spaniel), Twinkle (cocker), Prince Charming (her horse), Sweetheart (her brother’s horse), the other eight chipmunks she had and gave away and King Charles, the beautiful thoroughbred of “National Velvet.”

“They were afraid for me to ride him,” she’ll tell you gravely. “But he loves me. He wouldn’t hurt me. You don’t have to worry about King when you get on his back. You just leave everything up to him. I think he likes to know that I leave it to him. That he’s the boss and I trust him. You see horses are just like people. You’ve got to love them and trust them.”

She is very serious about her work, about the people she portrays. And often, though the director may be satisfied with a take on a picture, Elizabeth will beg, “Can’t we just try it one more time? I know I can do it better. I sort of feel it welling up inside me now.”

On the way home from the preview of “National Velvet” her mother asked her what she thought of it. “I’ve always loved Velvet, Mummy,” she said reverently. As though Velvet did it all.

Gentle is the word for Elizabeth. Just as she “gentled” the high-spirited horse she rode in that picture, so does she “gentle” everything and everyone with whom she comes in contact.

Her Hollywood beginning was different from that of most cinema children. Thirteen-year-old Elizabeth was born in London, England, the daughter of Francis Taylor, art dealer, and the former Sara Sothern, a pretty American actress who had been on the New York and London stages. She’s always loved horses and first learned to ride at the age of four when they were spending a summer vacation in Kent at the lodge estate of her godfather, Col. Victor Cazalet, since reported missing in action.

When she was seven and war seemed too near, her father sent the family to the States to stay with Mrs. Taylor’s father in Pasadena. Later he joined them, established an art gallery in Beverly Hills and they moved to the pretty Spanish-style stucco home where they live now.

Elizabeth loves story books, but her own story tops anything she could ever read. Although her parents had been approached by agents and others who thought she should be in pictures, they’d never considered it seriously.

Strangely enough it was her lovely coloratura voice (which hasn’t been used yet) that decided it. Elizabeth wanted to learn to sing “high—like a bird.” So she began taking singing lessons and soon could go within five notes of the end of the keyboard. She attended the same dancing school as the children of John Considine, M-G-M producer, and one day was overheard practicing by Mrs. Considine, who was so impressed that she called Louis B. Mayer and said, “You should hear her. She sounds just like a bird!”

So the next day there was Elizabeth in her little pinafore standing in the middle of a big office with several executives gathered around. They were enthusiastic and wanted to sign her. And Elizabeth, in turn, was very impressed by the big studio and the fascinating people with the make-believe faces (make-up). It looked like a real Never Never Land to her.

But since her parents had told Universal that they would give them first chance if she ever went into pictures, she signed there, instead, for a year. Nothing happened. And when the contract was up she signed with Metro with no more fanfare.

Sam Marx, M-G-M producer, who was then looking for a little English girl to play in “Lassie Come Home,” didn’t even know they’d signed a little girl with big luminous blue eyes who would love to play in a picture with a dog, especially an enchanting dog like Lassie.

It all happened three days later when Elizabeth’s daddy, who’s an air raid warden, went to an air raid wardens’ meeting and bumped into Sam Marx, warden in another block near them.

During the meeting somebody asked Marx how his picture was coming along.

“It’s almost finished,” he said, “but the girl is too tall for Roddy McDowall. We’re going to have to get a smaller child.”

“Have you seen Taylor’s little girl?” suggested somebody.

He said he hadn’t and told Warden Taylor to bring her over. Thus the next Sunday afternoon after church the Taylors dropped by the Marx home and the producer looked at Elizabeth and said, “Why haven’t I seen you before?”

She was visiting her grandparents in Pasadena when they got the wire to report to the studio that same afternoon for a test. They rushed over, but the tests were all finished and the crew was packing up their equipment when they dashed in. Director Freddie Wilcox told them to start rolling again.

After the test the cameraman and grips congratulated Elizabeth and told her, “You’ve got it, honey. You’re in.”

So, since anybody’s word is honest-truth to her, she told her mother, “Mummy, I’ve got the part.”

“No, darling. They haven’t seen the test,” her mother explained.

“They said I did,” said Elizabeth simply.

And, as it developed, she did.

She’d always loved Velvet, the little girl who shared her own love for horses. And when she finished “Lassie Come Home” and knew the studio was going to make the other one, she started wishing and praying a little ahead of time.

As a matter of fact, the studio had been going to make “National Velvet” for some twelve years but had never found the girl for Velvet. They tested Elizabeth and liked her very much, but as Pandro Berman, studio executive told her, “We’d love you for the part, Elizabeth, but you’re just too little.”

Sitting over in the comer with her heart in her eyes, Elizabeth said shyly, “Well—I’ll grow.”

“Honey, if you can grow I’ll wait for you,” the executive smiled. “I’ll wait three months—and you grow.”

“Don’t wait too long, Mr. Berman,” Mrs. Taylor broke in hurriedly. She had a lot of faith in her child—not without excellent reason—but this was certainly pushing it too far. “She hasn’t grown a quarter of an inch in three years!”

“But I will,” said Elizabeth. And did.

She ate more than she’d ever eaten in her life and added two hours of sleep each night. She began to ride and jump her red sorrel horse over the five-foot jumps at West Los Angeles Riviera Country Club several hours a day, training arduously for the jumps she’d have to take in the film. She went roller skating and learned to ride a bicycle. “Took a lot of falls too—that always helps,” she smiles now.

In three months she’d grown three inches. Until one day the producer took a startled look at her and said, “We’d better make this thing before you grow right on out of it.”

Ask Elizabeth how she thinks it really happened now and she says solemnly, “Well, I always prayed to God that if it was right for me to play Velvet that I would. I guess He thought it was okay.”

Somebody else who definitely thought it was okay was Producer-Director Clarence Brown, who considers Elizabeth’ a great little artist. “I really hate to call her an actress,” he says, wincing a little at the word. “She’s much too natural for that.” Which is highest praise from this star-maker, who has piloted Mickey Rooney, Jackie “Butch” Jenkins and others into fame.

He loves children and always fears a “star complex.” Thus, because of his great feeling for Elizabeth, he fairly exploded her first day on the set when he arrived early and saw a gold star on her dressing room door, a red carpet lushing from it and the words “Miss Taylor” impressively flourishing thereon.

He couldn’t stand to see her start out with two strikes against her.

So when she came he had a very serious heart-to-heart talk with her in which he explained that the red carpet must go, also the gold star and the “Miss Taylor.” Then he had an inspiration. “Why not’ change it to Velvet?” he said.

That night at home Elizabeth cried a little and sat down and wrote him a note that was so sweet and sincere he carried it around in his pocket for weeks. “I was so proud of it,” he says. In it she said that she knew what he was talking about and not to worry about her. “I’ll never get that way, Mr. Brown. Never! I promise!”

A promise to her is a cross-your-heart affair. As Freddie Wilcox found out recently when they were up at Lake Chelan, Washington, on location for “Hold High The Torch,” which was paradise to Elizabeth because it meant working for two months with Lassie and a whole menagerie of mountain lions, bobcats, beavers, squirrels and deer.

She loves stories and one day the director was telling her about something highly dramatic, when he was interrupted. He promised to call at her cabin that night and finish it—and didn’t. She treated him coolly for three days then, because she couldn’t stand it any longer, burst out, “Freddie, why didn’t you come the other night? You promised!”

She is very serious-minded and super-sensitive, and takes most everything literally as said. Honest-injun clear through.

Recently when a photographer was shooting pictures of her around the house and wanted a shot of her drying dishes, she protested, “Oh please don’t take that one. They’ll think I like drying dishes and kids everywhere will wonder what’s wrong with me.”

He went ahead and shot it but just when the camera flashed Elizabeth made such a terrible face—to keep it honest—that the still will probably never be used.

Yes—despite her great spiritual qualities—she’s still all girl.

Ask her what she doesn’t like and you’ll get a quickie—“Rice!” Or school work, with the exception of art classes, which she loves.

She has no knowledge of time for in her own Never Never Land there’s no such thing as a clock. It’s a major operation to get her off to school. An hour is fifteen minutes or a hundred and fifteen. And she doesn’t know or care which.

She likes tailored clothes, especially suits and a pearl-gray-colored anything. She goes into a trance over classical music, particularly Chopin. She likes to draw and paint, but fairly lives for Saturdays and Sundays when she and her fifteen-year-old brother Howard go riding at Dupee’s stables. Aside from that, all of her time is spent training her own pets. If she weren’t an actress, she’d like to be one of three things—a nurse, a jockey, or an animal trainer.

The yen to be the latter came at the age of four when she had her picture made with a chimpanzee at the London zoo. A chore which the chimp usually did with bored mien. One quickie and he wanted the kids out of his way. But when Elizabeth came up for hers, the big chimpanzee turned around and just looked at her thoughtfully, then put both arms around her and hugged her. The Taylors were terrified. Guards came running up and one of them had to hit the chimp with the butt of his gun to make him let her go. Elizabeth thought it was wonderful because the chimpanzee loved her so much. She decided to be an animal trainer.

Headquarters for her Never Never Land is her bedroom with its green chintz drapes, dressing table and bedspread with the long petticoat that’s ‘so handy for keeping things out of sight.

Near her bed is Nibbles’s little green house, made out of a bed table with a screen over the front of it, inside which he has a little log with real knotholes, where the chipmunk has made a nest by pulling cotton fuzz off the doll blanket Elizabeth gave him and packing the fuzz into the log.

There are twenty-one statues of horses scattered around on the dressing table, bureau and end tables, and pictures of Elizabeth and King Charles on the walls. On the big easel near the window is an almost finished picture of the magnificent horse. “King’s easy to draw—he’s so pretty,” she’ll tell you proudly.

A bridle dangles over the lamp bracket on one wall. There’s a new tan saddle riding the waste basket over in the corner. Another saddle—“a second-hand one I practice with” is draped over a doll’s cradle, with a limp French doll stretched languidly out in the saddle, one limber leg entwined in the stirrup, a surprised look on its chic face.

Sometimes in the night her room full of thoroughbreds come to life in her dream world and take to the air, with Elizabeth and King leading them over the jumps of the Grand National in “National Velvet” again.

“She really could have ridden the whole race in the picture, you know,” Director Clarence Brown tells you proudly.

She did ‘ride a goodly part of it and took many of the jumps, protesting brokenheartedly the occasional times that real jockeys or stunt men were used.

The double was all set to do the scene where Velvet runs into the road in the path of the horse to stop him from running away. “Mr. Brown, don’t you think it’s dangerous for him to do it?” cried Elizabeth. “He doesn’t know Bill. But he knows and loves me and he won’t trample me.”

The director and Mrs. Taylor finally consented. “Don’t worry—he’ll stop,” Elizabeth said.

King came out in high, the trainer cracked his whip, and the horse reared and tore off down the road, racing towards Elizabeth standing there so calmly at the other end. “There, there. Whoa, King,” she said soothingly. He whoaed. To those watching, it seemed to be a personal deal of faith between the horse and the little girl.

Knowing her faith in getting anything “that’s right” for her, someone recently asked her if there was anything she’d ever wanted that hadn’t come true.

“There is now,” she said, her voice trembling a little. “I want King.”

It seems there was some talk that the studio might give the horse to her, but her parents and others were afraid the spirited thoroughbred might be too dangerous.

“Oh NO! He wouldn’t hurt me! ” she said, her eyes filling with tears.

Then proving her point, she thought, Elizabeth reminded her mother of the time when she had had her head against King loving him and he’d taken the front of her blouse in his mouth and ripped it. “If he’d wanted to he could have taken my tummy then,” she reasoned.

When they try to settle for a different horse, she won’t have it.

“If you loved a person and nobody wanted you to and said somebody else was even prettier, you couldn’t change,” she says. “I don’t want King just because he’s beautiful. I wouldn’t care if he were an old nag. It’s just because it’s King,” she adds.

“If it isn’t right for you to have him, you wouldn’t want him, would you?” consoles her mother.

“I wouldn’t say I didn’t—want him,” she sobs, “but—”

So as far as Elizabeth is concerned it’s all in His lap. There’s another postscript on those prayers now. And you may be sure that every night down beside her green chintz bed, Elizabeth and God are going into a huddle again.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1945