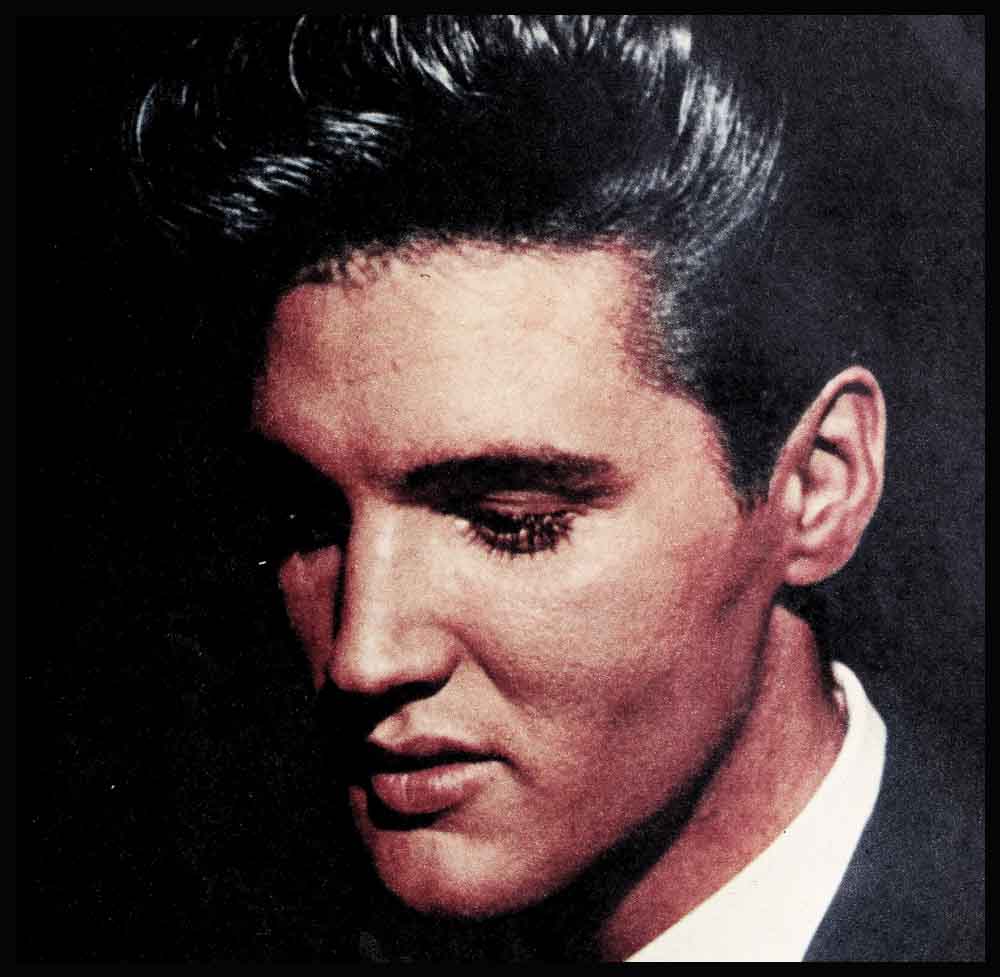

Elvis Presley: “Goodbye My Lover…”

“A fellow has to keep believing his girl is true to him . . . even if he knows she can’t be,” said Elvis Presley. “Common sense will tell any boy that a pretty girl can’t sit around doing nothing while they are a whole world apart. But he’d sure like to think that’s what she’s doing-yes, ma’am, a guy sure would like to think that.”

Elvis was in a setting that might have reminded him of his Army days in Germany. He was 7,000 feet high in the California mountains, whose peaks are reminiscent of the German Alps. The “Kid Galahad” company was on location at Idyllwild, California. If you’ve ever been there, you know it’s an ideal place to talk about loneliness.

On some of the mountain crests towering above the location site, solitary watch- men sit in lookout stations, keeping a lonesome vigil for forest fires. They come down about once every seven months and more than one member of the “Kid Galahad” company, eyeing the desolate posts, wondered what the men did to pass the time. A man has to do something when he’s lonely. He has to do something—or go crazy.

AUDIO BOOK

“Until you’ve had to leave everything behind.” Elvis went on. “you can’t imagine what it’s like. When I went into the Army, I’d been dating Anita Wood about two years. I thought about asking her to wait for me—you know—not to have dates while I was gone. But I couldn’t do that. It wouldn’t be fair.”

Elvis, famous for his courtly manners, doesn’t kiss and tell. But what he did say conjured up scenes of an unhappy young soldier about to go overseas, a soldier who was homesick before he even put one foot outside of Memphis. And in the scenes with him was his best girl, his “number one girl,” telling her best beau “Goodbye.”

Elvis has always brought his friends home. His mother, a sweet, hospitable woman, welcomed company even when the family lived in cramped quarters and only careful budgeting put food on the table.

No fun at Graceland

One of the reasons Elvis bought Graceland was to provide a big, comfortable place that his friends, as well as his family, could enjoy. Since the Presleys moved in, it has been the scene of swimming parties, picnics, dances and fun. But there was no fun at Graceland in the final weeks before Elvis went overseas. His mother had just died; Elvis and his father were crushed with a greater grief than they had imagined possible.

Walking through the quiet house still sickly sweet with the fragrance of funeral wreathes, Elvis turned into his mother’s room. Her dresses hung in the closet. Idly he opened and closed her bureau drawers until, in one, he found a shopping list. A Christmas list. She had started it months before Christmas but had not lived to use it. Elvis smoothed it down and carefully tucked it into his billfold. There were giant tears in his eyes.

As an only child, he’d been very close to his mother. With her gone, he must have clung fiercely to his best girl—Anita. He must have brought her to Graceland for their final hours together before he was shipped out.

Spitting cedar logs on the fire in the living room would have cast too faint a light to reflect tears, but Elvis must have felt the tears on Anita’s cheek as she and her soldier whispered farewell.

Gently, with one finger, he traced the contour of her face. She raised her hand to brush back a curl, and the smoothness of her finger s touching his hand had the impact of an electric shock.

Elvis’ chest felt so tight he could scarcely breathe. He was almost too choked to speak.

“I’ll miss you, Anita,” he promised, and she nodded . . . wondering . . . wishing . . . he’d say more.

“While I’m gone, I . . .” then Elvis paused without saying what he’d do while he was gone.

He had almost promised—he had almost said, “I won’t go out with another girl,” but he didn’t. He couldn’t make a pledge he knew he’d break.

“You’ll what?” the girl surely wondered.

“Oh, I’ll wish I were back here with you.” That’s what the soldier’s lips said—but his heart was saying “Please, please wait for me. Please wait for me. Don’t go out with other people. Just wait for me.”

More than once he nearly asked for a promise. Each time, though, a sense of fair play restrained him. Until the last minute of their last meeting, he struggled with a desire to hem in his girl with vows.

If he could be sure that someone was thinking only of him—if he only could—it would shorten the miles that they were apart—it would shorten the months they’d be apart. But his conscience kept telling him, “You’ll have dates while you’re gone and you can’t demand more of Anita than you would of yourself.”

As Elvis spoke of loneliness, of lovers saying goodbye, a grayish truck pulled into a parking space not far from where we sat. In the back of the truck, penned in by chain-link fencing, a dozen or more boys pressed their faces to the wire. None of them got out of the truck. They were wearing the prison uniform of a work-farm road gang. Many of them looked younger than Elvis—probably in their teens.

Why had the young prisoners who were working miles away been brought to the movie set? No one had an answer. We could only guess—guess that maybe their guard was curious to see how a motion picture was made. Guess that maybe be was the kind of a man who knew teenage prisoners would have something to talk about, something to write about after they had seen Elvis Presley. Whatever the reason, one thing was certain. More than one boy in the back of that truck would have understood what Elvis was saying about letters and loneliness. And so would a boy who had to leave his loved one to take a job in a new town. And so would a boy who had gone off to school. Loneliness is not limited to age, character or money. Loneliness affects everyone—everywhere.

“It makes time pass . . .”

“A girl doesn’t have to worry about a boy forgetting her while he’s away,” stated Elvis. “She’d be surprised to know how much he does think about her while they’re apart. If she keeps writing to him, he’ll remember her all right. He’ll remember her so much that that’s one reason he’s bound to go out with other girls. It makes the time pass faster. I know.”

Elvis could remember how the young soldiers in their barracks in Germany lay on their cots, playing cards and reading and rereading letters.

“Hey, Elvis,” one would call, “let’s go to town. I met this girl in a cafe last Saturday who said she’d be back tonight and bring a friend. How about it?”

Elvis was polishing a boot.

“Aw, I don’t know,” he said. “I don’t think so tonight. I’ve got to write some letters, so I think I’ll stay here. Thanks anyway.”

He held up the boot and was satisfied to discover a faint reflection in the toe. That was the way it should be.

Then, carefully placing the boots on the floor, he rummaged for paper and pen. Out of his billfold he pulled Anita’s last, much folded letter. The ink marks were faint in the folds of the paper, but between the folds her handwriting was clear and dearly familiar.

She wrote about the places they’d been together; about songs that were popular in Memphis now; never about other men or dates.

Rereading the closely-written pages, Elvis ached with wanting. He wanted to be able to pick up the phone and call old friends. He wanted to walk along the hometown streets and to kid with disc jockeys at the local radio station.

How many months would it be before he could do those wonderful things that he’d taken for granted?

He wanted to drive up in front of Anita’s house, too, and run up the steps and knock on the door. Then, pretty soon, he and his girl would be driving away through the humid dusk along some road they had driven over a hundred times.

Maybe they’d go over the Mississippi River bridge and have a hamburger in West Memphis, Arkansas.

Lights would bob on houseboats tied at the river’s edge. The high, squealing laughter from river bank shacks, the smell of frying catfish, sights and sounds of home—how he missed them!

Elvis closed his eyes and could see exactly the curve of the road as it left the bridge on the Arkansas side. The scent of the river would hang over the levee.

His girl would lean against him, and the soap-sweet fragrance of her hair would be more immediate, more overwhelming, than the river smells.

On a summer night, Nita would wear a cotton dress, crisp with starch. With his eyes still shut, Elvis tried to imagine she was sitting beside him. The dream-image, though, couldn’t fill his need.

He wanted to touch his girl’s soft hand. He wanted to hear her laugh when he had said something funny. He wanted to look at the silhouette of her throat in the deepening dusk as she leaned back against the car seat.

At the far end of the barracks, a radio was playing a song that had been popular four or five years before—“There is nothing like a dame—”

That did it.

“Hey,” Elvis called after the soldier who had asked him to go into town, “wait a minute. I’m going along.”

He stuffed the writing material into a table drawer as he jumped up. But the other soldier was gone.

“Nothing like a dame,” the radio continued to insist.

Elvis fished in his pocket for a dime as he ran toward the phone. In a minute he was dialing the number of a girl he knew in Berlin. Memphis was so many miles and so many months away and he was lonely.

Jealousy can backfire!

“If a girl never writes about the dates she’s having while her guy is away,” Elvis said, pitching a piece of bread to a squirrel that ventured nearby, “when he gets home, they can both pretend she didn’t have any.

“Don’t think a girl keeps a boy more interested by making him jealous.”

When Elvis came home, he was mobbed by reporters, photographers and other interview seekers. Even his close friend, Nick Adams, trying to call him from Hollywood, had trouble getting a call through.

So, for a while, because of the press of people, Elvis and Anita had no opportunity to talk about the months they had been apart. Finally the opportunity came—but they talked of other things. Their eyes and their smiles said “It’s good the waiting has ended”—but neither of them asked, “How did you spend your time, who did you date, what was that l heard about you and so-and-so while we were a world apart?”

“I knew,” Elvis told me, “that she had been dating other people. And she knew I had been dating. But since neither of us mentioned it, we could pretend that it never happened. We could pick up where we left off!”

Today, Anita and Elvis are still dating. While Elvis is in Hollywood, his dates with other girls are duly reported by columnists. But when he goes home to Memphis, it’s Anita he sees and only Anita. Sometimes when Elvis is lonely, like last Thanksgiving and Christmas, Anita comes to Hollywood to see him. They aren’t married—no, not even officially engaged—but because Anita has behaved as Elvis feels a girl should after she says, “Goodbye My Lover,” it looks as if she’s the number one candidate to be Mrs. Elvis Presley.

—NANCY ANDERSON

Elvis is in “Follow That Dream,” UA.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1962

AUDIO BOOK