Love Song For Judy Garland

PART II

There is one thing about Judy Garland—maybe because she has music all the way through her: She is literally like a haunting melody. After you’ve been with her for any length of time, you remember her for days. You find yourself smiling and thinking of some little thing she did, of her enormous youthful gravity when she is serious about anything, of her rich chuckle when she is amused, of the impression of littleness and fragility she gives.

“I’ve put on ten pounds,” Judy told me. “Isn’t it wonderful?”

“I thought maybe you had that modem idea of being so terribly thin,” I said.

AUDIO BOOK

“Me?” said Judy, and chuckled. “Of course when I was a kid I was chunky as anything. So then I was always trying to take off weight. It was awful! I had an appetite and I guess I was growing and I was always hungry—so I just couldn’t diet. So I used to exercise. But it never did any good—I stayed chunky. Then all of a sudden I got thin. And I was too thin. So then I had to start trying to get fat. Now I’ve put on ten pounds—and I think that’s about right.”

The day Judy invited me over to ha ve lunch with her and Vincente Minnelli, she was late. She’s nearly always a few minutes late for everything; she’s even late on the set.

“Where’s the baby?” somebody will say. (She is still M-G-M’s “baby ”)

“She’ll be along,” somebody else says.

“The point is,” says Miss Garland in explanation, “there’s only one of me. I have to be in so many different places at the same time.”

The truth is that she is interested in so many things— music first and foremost, the young American composers, the great conductors, the political significance of Wagner’s unquestioned genius. She is interested in every detail in the war, in sports and the nickel World Series in St. Louis, in collecting china, in the writers who have been produced by the war and the books they’ve written. She’s interested in everything that takes place in Washington. I don’t mean just surface patter—I don’t mean that she’s an intellectual. She’s just vitally interested in everything that’s going on in the world, which, of course, makes for richness of personality.

The first time we had talked about the possibility of her marrying Vincente Minnelli was just before Christmas and her engagement to him had not yet been announced.

“I made one mistake,” Judy said then. When she looks at you seriously like that her eyes get darker and darker, shadowed by the intensity of her inner thoughts, by her all-out integrity about herself. “I don’t want to make another.

“I love my work. I know there are girls who can give up their work and get married and just live at home. I don’t believe I could. I don’t believe I’d be happy. You see—

Somebody came in with some papers for her to sign, the wardrobe wanted to know if she’d be ready for a fitting at three, her secretary handed her a list and Judy said, “These are the nobody-can-do-them-but-me things. You know about those.”

After a while she went on, “You see—my father and I were very close. He loved music and the theater and everything about it. He sort of planted it in me and when I was little and they found out I could sing—he began to train me. I wasn’t more than a foot high, I guess. My mother thought I could do something long before anybody else did—she thought I could maybe even act someday. We always belonged in the theater. I know that lots of stars say they’d like to re tire and I know some girls who really can occupy their lives other ways—but—I’ve been singing and dancing and acting since I was two— ten years in vaudeville and ten in pictures. That’s all my life. I don’t believe I could ever be really happy and fulfilled without it now. But I do want babies awfully.”

She took time out then to tell me about her young niece, her sister’s little girl, who is five. It must be great fun to have Judy Garland for an aunt. Like every other aunt, Judy told a dozen stories about little Judy, her namesake and godchild, and they were just like all the other cute stories about five-year-old children but you could tell that Judy thought they were something very special indeed—and I liked that.

“So—it has to be somebody that understands about me and my work and thinks it’s important and—we have to work together,” Judy said. ‘Vincente is wonderful. He’s the most interesting man I’ve ever known. He knows everything in the world, honestly, it just amazes me—he’s read everything and heard every piece of music and been everywhere but you’d never think it just to meet him, he’s so quiet and rather shy and always making you laugh. But he puts work first. I don’t know yet—maybe it will be right for us. We both know that a marriage can either be the most wonderful thing on earth or it can gum up your whole life and spoil everything, including your work. We— we’re thinking it over.”

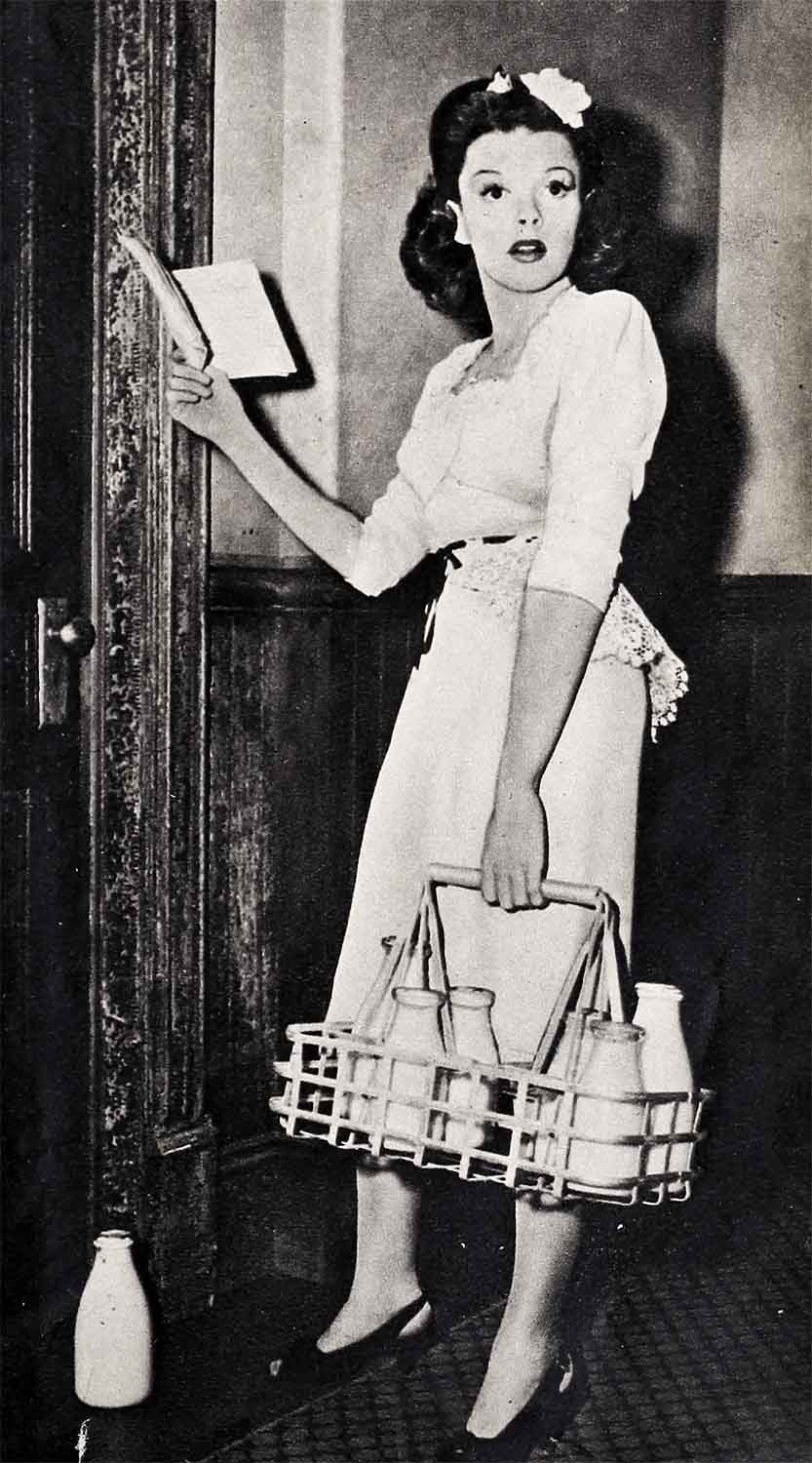

“The Clock” inspired this milkmaid shot of Judy

I remember I went away that day wondering how long two people in love can think about anything and then I realized that perhaps Judy didn’t know how much in love she was. Perhaps because it was all so eminently right, be cause everybody at the studio from Papa Mayer down was tickled about it and feeling it was so fine for Judy—perhaps she just couldn’t quite believe it. I thought it was a little tough on Mr. Minnelli to have everybody approve of him to such a terrific extent, because girls are very funny about that and sometimes they don’t think it is altogether romantic to have fallen in love with a man that the family cheers for. I went away with a feeling that maybe nothing would come of this romance, that maybe it would be smothered by well-wishing friends and family and studio.

But then Judy called me and I went over to lunch. We sat there talking about a lot of things and then Judy picked up the telephone and called the commissary. She was right fussy about Mr. Minnelli’s lunch. His coffee had to be hot and were the veal chops nice or had he better have chicken and did they have any cottage cheese salad? There was a great deal of consultation before she decided on the veal chops.

The veal chops came with piping hot coffee and all was set out on the small table under Judy’s eye—and she reset it twice and got a little vase of flowers, and stood off and looked at it. We talked some more and still Mr. Minnelli didn’t arrive. Judy got up and wrapped a napkin around the hot coffee and peered under the lid at the veal chops. “Do you think they’ll be ruined?” she said. “I expect they will. Cold gravy is awful.”

After a while she went to the phone and called Mr. Minnelli’s office. “He’s supposed to be here,” she said, with a chuckle. “He never knows what time it is. It’s wonderful. He gets interested in his work or something and just forgets everything.”

The door burst open and Vincente Minnelli came in talking a mile a minute.

It is very difficult to convey his charm on paper. I thought—but he is very young—very young to be so successful. He can’t be so young as Judy of course but—he has that same quality of youth. (As a matter of fact I found out later he is thirty-four.) He’s what I call an attractive ugly man—or at least for the first few minutes that was what I thought. Then I decided that he was attractive and then I forgot all about it, and just knew that he was utterly real and unselfconscious and full of that rare enthusiasm for living that makes everything and everybody around him come to life.

He was born in Chicago of Italian parents and his earliest ambition was the theater. So as soon as he could he went to New York and that swift understanding and enthusiasm carried him on a wave into some of the best musical shows New York ever had, as a stage director. Before he was thirty he had done half a dozen of them—and then he came to Hollywood.

The other day in the projection room I saw a picture called “The Clock.” It stars Judy Garland and Bob Walker, was written by Paul and Pauline Gallico, adapted to the screen by Robert Nathan and directed by Vincente Minnelli. “The Clock” has a sort of charm and honesty and reality beyond any other picture I have seen in a long time; it has a poignancy that reaches out and touches your heart. It’s one of the greatest and most moving love stories I have ever seen on the screen.

When I saw it I couldn’t quite explain it—but after I met Vincente Minnelli I could. Also I could understand him better.

“Your lunch is probably cold,” Judy said, beaming upon him. “Did you forget about us?”

“Forget?” said Mr. Minnelli, “but, darling, I am quite early. I was over in Cedric Gibbons’s office. It seems that I want too many sets. Or they are too expensive or something.”

“I expect you got them just the same,” said Miss Garland.

“Well yes—I did, as a matter of fact,” said Mr. Minnelli. His dark eyes twinkled at her. “I explained about them you see and then he understood how necessary they were.”

“Anybody who starts listening to you explaining,” said Judy, “is nuts. Eat your lunch. Is the coffee hot enough?”

It was stone cold, but Vincente smiled brightly and said it was splendid.

I looked at them and thought they were a very fine pair of typical and representative young Americans. Judy sat in a straight chair with one foot under her. The stiff little white shirtwaist with a severe black bow and the straight tailored skirt of black and white checks gave her a trim, neat look—an oddly feminine look. Minnelli, in worn and sloppy tweeds with a sweater instead of a shirt, sprawled at ease on the big divan, never taking his eyes off her. Every move she made, every word she said, seemed to give him a real and evident delight.

We talked about the dialogue—which is so all-important to pictures. Minnelli said that he was in favor always of as little dialogue as possible. We talked about that classic made by the Army Air Force, “The Memphis Belle,” and of the simplicity and power of the real things the crew said to each other in the midst of battle.

“When you see a thing like that,” said Vincente Minnelli, “you get on your toes and wonder if even Shakespeare could equal the sheer drama of reality.”

They were excited about a concert they had heard with Yehudi Menuhin at his best—and about a new Tommy Dorsey, recording—and about house furnishings. Vincente said, “Judy is a very remarkable woman. She knows that chairs should be comfortable to sit in. Oddly enough, very ‘ few women know that.”

It came over me all of a sudden that here were two people not only very much in love but presenting that oneness, that unity of purpose and intent that is so reassuring. You could see them supplementing each other, supporting each other, maybe fighting once in a while, but meeting shoulder to shoulder the many problems of a Hollywood star’s marriage. You could see there would be gaiety and tenderness and maybe pain in their lives—but always that oneness, that unity. So that things would draw them together instead of driving them apart. You felt glad that there was such equality between them, this brilliant young director about whose future everyone is so enthusiastic and the young star everyone loves.

So that the people who love Judy Garland on the screen can all say, as I did—this is right, this is all right—and wish them the happiness and the progress together that I saw so plainly between them.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1945

AUDIO BOOK